Introduction

History and Evolution of the Concept of Patient Safety

The practice of medicine, aptly described by Samuel Johnson as ‘the greatest benefit to mankind’, has and always will be associated with inherent risks.1 This has been acknowledged for as long as medicine itself has existed: the Ancient Greeks’ words for ‘kill’ and ‘cure’ were similar and the Hippocratic Oath contains the promise ‘to abstain from doing harm’, later adapted by Thomas Sydenham into the famous phrase ‘primum non nocere’ or ‘first do no harm’.

Perhaps surprisingly, it has only been relatively recently that these risks, their causes and ways to ameliorate them have been subjected to rigorous academic study. One of the earliest specific observations of patient harm was made in the nineteenth century by Florence Nightingale regarding infection in hospitals, a new and devastating problem at the time. In the 1960s, more systematic studies of hospital-associated harm began to be carried out, initially driven by the development of litigation. In more recent times, perhaps triggered by high-profile events such as the Bristol Heart Inquiry and landmark international reports such as An Organization with a Memory2 in the UK and To Err is Human3 in the USA, patient safety has become the focus of much attention. It is now recognized globally as one of the top priorities in healthcare and, as our understanding of healthcare-related harm deepens, so our ability to improve it grows.

In this chapter, we describe some of the current knowledge about patient safety and how this relates to the care of older people.

Definitions

Patient safety may be defined as ‘the prevention and amelioration of adverse outcomes or injuries stemming from the process of healthcare’.4 This definition encompasses not only the avoidance of individual error or harm and the high reliability of healthcare systems, but also the appropriate management of healthcare-associated harm: not just in terms of appropriate immediate medical management, but also in supporting staff, patients and their families.

Patient safety is just one aspect of high-quality care. In the recent UK report High Quality Care for All,5 quality of care, defined from a patient’s point of view, encompasses safety, experience and outcomes. In the USA, ‘Crossing the quality chasm’ similarly described the elements of quality as safety, effectiveness, patient-centredness, timeliness, efficiency and equitableness. Safety has been described as ‘the dark side of quality’ because of its historical association with litigation and blame, but it is increasingly acknowledged that efforts to learn more about and improve safety are themselves a feature of high-quality healthcare organizations.1

Measurement—The Scale of Harm

There are several ways to measure or estimate the extent of errors or adverse events in healthcare, including analysis of administrative or reporting data, case record review, observations of patient care and active clinical surveillance. Each of these methods has its advantages and disadvantages, in terms of availability of data, cost, reliability, observer bias and clinical relevance. Clearly, the measurement of safety overlaps with the measurement of quality of care, described in Chapters 137 and 138.

An adverse event is defined as an unintended injury caused by medical management rather than the disease process, which is sufficiently serious to lead to prolongation of hospitalization or to temporary or permanent disability or death.4 This definition is important because it has been traditionally used in studies of the nature and scale of harm, described below.

A critical incident or ‘near miss’ may be considered to be the next step down from this—incidents which may have caused harm but did not actually do so.

Over the last 40 years, a number of international adverse event studies have been published, in which retrospective case record review was used to identify adverse events in order to assess the nature and scale of harm in acute hospitals.

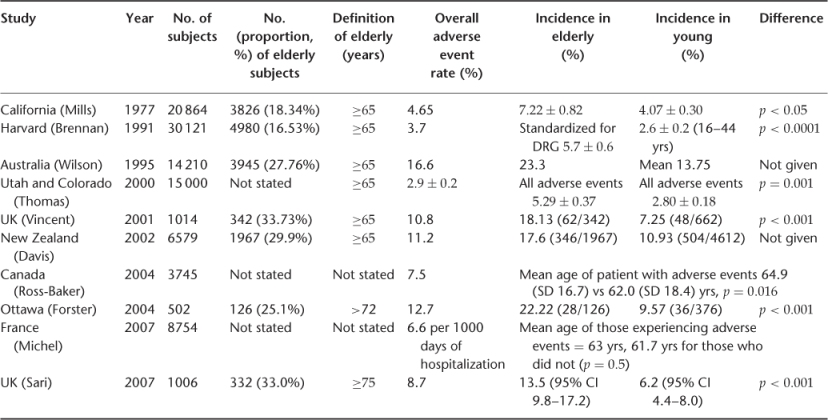

A selection of these studies are shown in Table 14.1. Rates of adverse events in most recent studies lie between 8 and 12%, a range now accepted as being typical of advanced healthcare systems. The rate per patient is always slightly higher, as some patients suffer more than one event and about half of adverse events are generally judged to be preventable. United States rates are much lower, Australian seemingly much higher. The lower US rates might reflect better quality care, but most probably reflect the narrower focus on negligent injury rather than the broader quality improvement focus of most other studies.

Table 14.1 International adverse events studies, showing data for older patients.

Studies of Errors

There are a number of methods of studying errors and adverse events, each of which has evolved over time and been adapted to different contexts.6 Each of the methods has particular advantages and disadvantages. Some methods are oriented towards detecting incidence of errors and adverse events (Table 14.2), whereas others address their causes and contributory factors (Table 14.3). There is no perfect way of estimating the incidence of adverse events or of errors. For various reasons, all of them give a partial picture. Any retrospective review is vulnerable to hindsight or outcome, bias, where knowledge that the outcome was bad leads to unjust simplification and criticism of preceding events. Record review is comprehensive and systematic, but by definition is restricted to matters noted in the medical record. Reporting systems are strongly dependent on the willingness of staff to report and are a very imperfect reflection of the underlying rate of errors or adverse events.

Table 14.2 Methods of measuring errors and adverse events.

| Study method | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Administrative data analysis | Uses readily available data | May rely upon incomplete and inaccurate data |

| Inexpensive | The data are divorced from clinical context | |

| Record review/chart review | Uses readily available data | Judgements about adverse events not reliable |

| Commonly used | Medical records are incomplete | |

| Hindsight bias | ||

| Review of electronic medical record | Inexpensive after initial investment | Susceptible to programming and/or data entry errors |

| Monitors in real time | Expensive to implement | |

| Integrates multiple data sources | ||

| Observation of patient care | Potentially accurate and precise | Time consuming and expensive |

| Provides data otherwise unavailable | Difficult to train reliable observers | |

| Detects more active errors than other | Potential concerns about confidentiality | |

| methods | Possible to be overwhelmed with information | |

| Active clinical surveillance | Potentially accurate and precise for adverse events | Time consuming and expensive |

Source: adapted from Thomas and Petersen.6

Table 14.3 Methods of understanding errors and adverse events.

| Study method | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Morbidity and mortality | Can suggest contributory factors | Hindsight bias |

| conferences and autopsy | Familiar to healthcare providers | Reporting bias |

| Focused on diagnostic errors | ||

| Infrequently used | ||

| Case analysis/root cause analysis | Can suggest contributory structured systems approach | Hindsight bias |

| Includes recent data from interviews | Tends to focus on severe events | |

| Insufficiently standardized in practice | ||

| Claims analysis | Provides multiple perspectives | Hindsight bias |

| (patients, providers, lawyers) | Reporting bias | |

| Non-standardized source of data | ||

| Error reporting systems | Provide multiple perspectives over time | Reporting bias |

| Can be a part of routine operations | Hindsight bias |

Source: adapted from Thomas and Petersen.6

Why do Adverse Events Occur?

In order to obtain a true understanding of patient safety, it is not enough just to assess the scale of healthcare-associated harm: we have to look deeper to understand the processes that underlie it. As described later, attempts to understand the causes of adverse events are routinely made within individual organizations in several ways, such as through local morbidity and mortality meetings or through the use of more structured approaches such as root cause analysis.

Learning from Other Industries

On a more general level, many methods have been employed by patient safety researchers to enhance our knowledge of the causes of adverse events. It is important to appreciate that when an adverse event occurs we may be quick to judge or blame the actions or omissions of individuals, but careful inquiry usually shows us that deficiencies in our systems are also at fault. We have learnt much from other industries in this respect. Investigation of major disasters such as the Chernobyl nuclear explosion, the Space Shuttle Challenger crash and the Paddington rail accident identified ‘violations of procedure’ or problems that occurred as the result of actions or omissions by people at the scene. However, further analysis of these events revealed ‘latent conditions’7 further upstream in the process, which allowed these violations to occur and have such a devastating effect. ‘Latent conditions’ are often a result of gradual and unintentional erosion of safety-enhancing processes because of other pressures, for example, cutting training budgets because of financial costs. Further still in the background are often deeply ingrained cultural and organizational issues, some of which may be elusive and difficult to resolve.

Of course, it is all very well to learn about the underlying causes of these non-healthcare-related disasters, but the question that most clinicians will ask at this stage is what relevance this has to us. Although healthcare is similar to these industries in some respects, such as the high level of inherent risks and the well-meaning and dedication of its staff, it is very different in others—such as in its diversity, often non-centralized administration, uncertainty and unpredictability.

Human Error

Human error is not easy to define, as boundaries are often blurred between the actions or inactions of individuals and the deficiencies of the systems in which they work. However, it is important to try to define and classify different sorts of error in medicine, largely because this may help us to learn from incidents. We can think about errors in medicine in relation to the clinical processes involved, for example, prescribing errors or diagnostic errors, but perhaps it is also useful to look at the underlying psychological themes. In his analysis of different types of error, Reason8 divided them into two broad types of error: slips and lapses, which are errors of action and mistakes which are, broadly speaking, errors of knowledge or planning. He also discusses violations that, as distinct from error, are intentional acts which, for one reason or another, deviate from the usual or expected course of action.

Delays and errors in clinical decision-making are particularly critical in medicine and there is an extensive literature about the complexities of medical decision-making.9 In our daily clinical practice, we use heuristics, which are simple but approximate rules to aid decision-making by simplifying the situation and decision to be made. Particularly at times of fatigue, stress or time pressure, these heuristics can become ‘biases’, leading to faulty clinical decision-making leading to undesirable consequences.10 Some of these, with common clinical examples, are given in Table 14.4.

Table 14.4 Examples of some cognitive biases and heuristics that commonly affect clinical reasoning.

| Name | Definition | Example |

| Availability heuristic | Making judgements based on cases that spring easily to mind | ‘The last time I saw a patient with fever and a headache it was only flu, so it is likely to be so in this case too’ (actually meningitis) |

| Anchoring heuristic | Sticking with initial impressions | The confused elderly patient who has a ‘UTI’ on admission (despite a negative MSU), whose severe constipation goes unnoticed |

| Framing effects | Making a decision based on how the information is presented to you | ‘A&E referred this patient with fever and haemoptysis as “pneumonia” so that is the most likely diagnosis even though the CXR is normal’ (actually a PE) |

| Blind obedience | Showing undue deference to seniority or technology—‘they must be right and I must be wrong’! | ‘My consultant said that this patient could go home, so I am going to ignore concerns raised by nursing staff’ ‘The blood results show a normal haemoglobin even though this patient looks clinically anaemic—the blood results must be right’ |

| Premature closure | Being satisfied too easily with an explanation | In a patient with staphylococcal sepsis, assuming the source of sepsis is their cellulitic leg, and missing their underlying endocarditis |

Source: adapted from Redelmeier.10

System and Organizational Factors

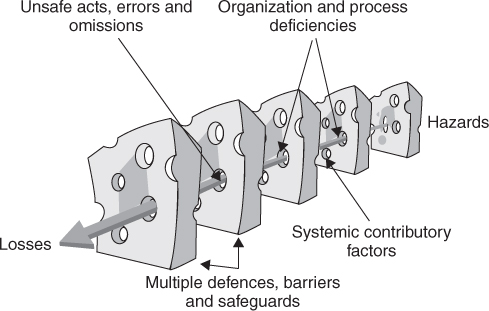

Errors and human behaviour cannot be understood in isolation, but only in relation to the context in which people are working. Clinical staff are influenced by the nature of the task they are carrying out, the team they work in, their working environment and the wider organizational context; these are the system factors. The systems in which we work have inbuilt defences and barriers and it is only when these defences are simultaneously breached that adverse events occur. This concept forms the basis of Reason’s ‘Swiss cheese model’, shown in Figure 14.1.

Learning from high-reliability organizations in other industries, which achieve high levels of safety and performance in the face of considerable hazards and operational complexity, is an ongoing challenge to improving safety in healthcare. Important characteristic of these types of organizations are safety culture and leadership: there is some evidence that these are related to some measures of safety in healthcare.

Analyses of incidents usually reveal the causes to be a combination of all of the factors described above. This can be summarized by ‘the seven-level framework’,11 which conceptualizes the patient, task and technology, staff, team, working environment and organizational and institutional environmental factors that influence clinical practice. This is shown in Table 14.5.

Table 14.5 The seven-level framework.

| Factor types | Contributory influencing factor |

| Patient factors | Condition (complexity and seriousness) |

| Language and communication | |

| Personality and social factors | |

| Task and technology factors | Task design and clarity of structure |

| Availability and use of protocols | |

| Availability and accuracy of test results | |

| Decision-making aids | |

| Individual (staff) factors | Knowledge and skills |

| Competence | |

| Physical and mental health | |

| Team factors | Verbal communication |

| Written communication | |

| Supervision and seeking help | |

| Team leadership | |

| Work environmental factors | Staffing levels and skills mix |

| Workload and shift patterns | |

| Design, availability and maintenance of equipment | |

| Administrative and managerial support | |

| Physical environment | |

| Organizational and management factors | Financial resources and constraints |

| Organizational structure | |

| Policy, standards and goals | |

| Safety culture and priorities | |

| Institutional context factors | Economic and regulatory context |

| National health service executive | |

| Links with external organisations |

Source: from Vincent et al.11

What Happens after An Adverse Event?

Reporting and Learning

There are a variety of reporting systems operating at different levels within healthcare systems across the world. Some operate primarily at local level (risk management systems in hospitals), others at regional or national level. Local systems are ideally used as part of an overall safety and quality improvement strategy, but in practice may be dominated by managing claims and complaints. Many different clinical specialities, particularly anaesthesia, have established reporting systems to assist them in improving clinical practice. These systems are designed to provide information on specific clinical issues which can be shared within the professional group. The increasing attention paid to patient safety has led to the establishment of many new reporting and learning systems, most notably, in the UK, the Reporting and Learning System (RLS) established by the National Patient Safety Agency. Other national reporting systems include the wide-ranging Veterans Affairs system in the USA and the Australian Incident Monitoring System (AIMS).

The main purpose of reporting systems is to communicate information about patient safety issues, so that learning and improvement of systems and practice can occur. A secondary benefit of these systems is that we can use them to assess the scale of harm and identify trends.

There are inherent problems with all reporting systems in healthcare: most studies have found that reporting systems only detect 7–15% of adverse events,12 when compared with other methods of detection such as case record review. Some of the common barriers to reporting include a fear of embarrassment, punishment by oneself or others, fear of litigation, lack of feedback and a belief that nothing will be done in response to reporting.

Understanding Why Things Go Wrong

The investigation and analysis of cases in which clinical incidents have occurred can be used to illustrate the process of clinical decision-making, the weighing of treatment options and sometimes, particularly when errors are discussed, the personal impact of incidents and mishaps, and critically also includes reflection on the broader healthcare system. There are a number of methods of investigation and analysis used in healthcare, either retrospectively, for example root cause analysis or systems analysis of events, or prospectively, for example failure modes and effects analysis (FMEA).

Caring for Patients After An Adverse Event

Patients and relatives may suffer in two distinct ways from a medical-induced injury: first from the injury itself and second from the way in which the incident is handled afterwards. Many people harmed by their treatment suffer further trauma through the incident being insensitively and incompetently handled. Conversely, when staff come forward, acknowledge the damage and take positive action, the support offered can ameliorate the impact in both the short and long term. Injured patients and their families need open disclosure: an explanation, an apology, or to know that changes have been made to prevent future incidents, and often also need practical and financial help.13

Supporting Staff

Making an error, particularly if a patient is harmed because of it, may have profound emotional or psychological consequences for the staff involved. This in turn can make future errors more likely and affect teamwork. Factors which may make this more likely include the severity of the error and the reactions of those involved, attitudes to error, beliefs about control and the power of medicine and the impact of litigation. Strategies to minimize the effects of adverse events on staff include wider acknowledgement of the potential for error, having an agreed policy on openness with injured patients, encouraging support from colleagues, education and training and, if necessary, formal support and access to confidential counselling.

Patient Safety and Older People

The Incidence of Adverse Events in Older People in Hospital

Re-Analysis of the International Adverse Event Studies

There is considerable evidence that older people suffer a higher incidence of adverse events than their younger counterparts in hospital. The landmark, international, adverse event studies described in Table 14.1 investigated the incidence and types of adverse events in hospital inpatients of all ages. This was achieved by two-stage retrospective case record review in the majority of cases. Table 14.1 also shows that if the results of these large studies are re-analysed to consider specifically the effects of age on patterns and frequencies of adverse events, they all show that age is a risk factor for adverse events. However, when this relationship is examined more closely, it emerges that it is co-morbidity, rather than age alone, that appears to be responsible for this association. In addition to experiencing more adverse events, older people also suffer more serious consequences of adverse events in the majority of studies, in terms of morbidity and mortality, increased dependence, increased hospital stay and a greater chance of institutionalization;14 again, this seems to be related to their physical vulnerability, in terms of frailty and diminished physiological reserve. As might be expected, data from these studies show that older people in hospital tend to experience different types of adverse events than their younger counterparts, such as falls, hospital-acquired infections and drug errors rather than complications related to invasive procedures. In general, it seems that it is controversial as to whether adverse events are more preventable in elderly than in younger patients.

Data from Reporting Systems

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree