PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Any disorder of the breast is viewed by the patient with alarm. Although, with the exception of carcinoma, disorders of the breast are not life threatening, any deviation from normal size and appearance must be thoroughly evaluated. Because the development of the breasts is hormone dependent and breast disorders either may have a hormonal etiology or may be misconstrued as having a hormonal cause, the endocrinologist should be familiar with the pathophysiology of these organs.

DEVELOPMENTAL ANOMALIES

It was not until 1969 that a system for classifying breast development was established by Marshall and Tanner9 (see Chap. 91). In addition to its obvious use in evaluating the adequacy of breast development, this classification can be used to determine the presence of pathology.

CONGENITAL ANOMALIES

Congenital anomalies of the breast itself are uncommon; however, one frequently sees anomalies of development. Even so, amastia, congenital absence of the breast; athelia, congenital absence of the nipple; polymastia, multiple breasts; polythelia, multiple nipples; or some combination, occur in 1% to 2% of the population and may have a familial tendency.44 If treatment is deemed necessary, surgical augmentation or excision is recommended (Fig. 106-2).

Young patients may present with the problem of premature thelarche (see Chap. 92). Many would define this condition as breast development beginning before age 8. Affected individuals may have either bilateral or unilateral development. The disorder may be differentiated from precocious puberty by the finding of prepubertal serum levels of gonadotropin and estrogen. Precocious thelarche is self-limited and demands no therapy other than assurance, once complete or incomplete isosexual precocity has been ruled out.

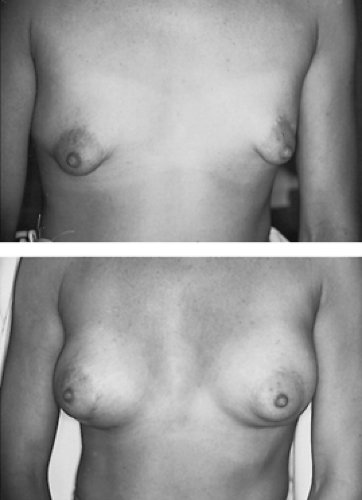

BREAST ASYMMETRY

Breast asymmetry is fairly common (Fig. 106-3) and presumably is secondary to a difference in end-organ sensitivity to estrogen and progesterone. Occasionally, full symmetry is obtained in adolescents by the administration of an oral contraceptive agent, although either augmentation or reduction mammoplasty may be required if severe asymmetry does not resolve. Most patients with breast asymmetry do not require therapy other than reassurance that this is simply a variation of normal.

HYPOPLASIA OF THE BREASTS

Perhaps one of the most common disorders of the breast involves hypoplasia. These individuals may simply have small breasts secondary to a transient delay in puberty or may have a genetic tendency toward hypoplasia, with other siblings having similar problems. Such breasts show a physiologic response to pregnancy, and lactation can follow. Not uncommonly, because of social pressure to have “normal-sized” breasts, augmentation is often sought by affected individuals (Fig. 106-4). Such augmentation will not interfere with lactation or breast-feeding but does increase the difficulty of self-examination and surveillance for breast malignancies. Breast hypoplasia is sometimes found in patients with severe anorexia nervosa and other variants of psychogenic amenorrhea associated with decreased body weight or extremes of exercise (see Chap. 128); such individuals have an altered fat/lean mass body ratio, which generally renders them hypogonadotropic and hypoestrogenic. The removal of estrogen-progesterone stimulation leads to breast atrophy. Reconstructive therapy is contraindicated in this group; correction of nutritional requirements is the therapy of choice, although this must often be accompanied by psychotherapy in patients with emotionally related weight loss.

Breast hypoplasia also occurs in the female pseudohermaphroditism of congenital adrenal hyperplasia (see Chap. 77) and in Turner syndrome (see Chap. 90). The early institution of corticosteroid therapy will greatly benefit the former patient; the latter should be treated at the appropriate time with cyclical estrogen and progesterone.

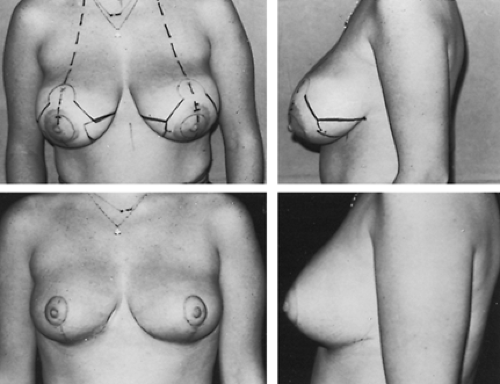

BREAST HYPERTROPHY

Breast hypertrophy or macromastia is encountered commonly in both adolescents and adults. The breasts may be either symmetric or asymmetric. The patient frequently presents seeking advice on reduction mammoplasty (Fig. 106-5), perhaps because of chest wall pain secondary to the weight of the breasts, difficulty in finding clothes that fit the upper body, and difficulty with her self-image. Frequently, young women are under intense sexual pressure and are often embarrassed by

peers during gymnasium classes or when wearing swimming suits. As an alternative to surgical correction, danazol has been tried.45 Unfortunately, this drug has many side effects and definitely is not acceptable for long-term therapy.

peers during gymnasium classes or when wearing swimming suits. As an alternative to surgical correction, danazol has been tried.45 Unfortunately, this drug has many side effects and definitely is not acceptable for long-term therapy.

NIPPLE INVERSION

Nipple inversion is common but rarely presents as a complaint to the clinician. Cosmetic repair can be performed, but breast-feeding is difficult after such procedures.

GALACTORRHEA

Galactorrhea, the inappropriate production and secretion of milk, may be intermittent or continuous, bilateral or unilateral, free flowing or expressible. By definition, fat droplets must be present on microscopic examination for a breast secretion to be considered milk and as evidence of galactorrhea. Galactorrhea is frequently associated with hyperprolactinemia (see Chap. 13),46 which should be sought by repeatedly measuring serum prolactin levels, remembering that prolactin is a stress-related hormone whose secretion may be increased by breast examination and stimulation, acute exercise, food intake (particularly protein), and sleep.47 Although the differential diagnosis of hyperprolactinemia is extensive, the common causes of this condition are prolactinoma, primary hypothyroidism, and drug intake. Galactorrhea should be evaluated by the measurement of multiple serum prolactin levels, thyroxine, and thyroid-stimulating hormone and by radiographic or magnetic resonance imaging studies of the pituitary. The prolactin level at which radiographic surveillance is begun is debated; however, computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging should be done if basal prolactin levels exceed 100 ng/mL. Galactorrhea and its treatment are considered in more detail in Chapter 13, Chapter 21, Chapter 22 and Chapter 23.

MASTODYNIA

Mastodynia, painful engorgement of the breasts, is usually cyclic, becoming worse before menstruation.48 Although most women describe mastodynia at some times, they require no therapy. However, some patients require cyclic analgesics or nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. Occasionally mastodynia is a complaint of women experiencing the premenstrual syndrome; some affected patients will sporadically obtain some relief with nonspecific therapy, as discussed in Chapter 99. Mastodynia may also be treated effectively with danazol, but the side effects of the drug mandate its use only in severe cases.

In addition, a second generation of drugs, the GnRH analogs, have been used to induce hypogonadotropism and hypoestrogenism, thus treating disorders such as endometriosis, fibroids, hirsutism, and premenstrual syndrome. Treatment with these agents, either on a daily or monthly basis, will result in profound hypogonadism, breast atrophy, and relief of mastodynia. These drugs are not approved by the Food and Drug Administration for this purpose, and therapy beyond 6 months results in reversible bone demineralization. To compensate for this loss in other disorders, estrogen “add-back” therapy, cotreatment with progestogens, and the use of variable-dose estrogen-progestogen overlapping protocols have been used to counter this and other side effects.

BREAST INFECTIONS

Breast infections are often confused with galactorrhea but require therapy with appropriate systemic antibiotics. Patients present with unilateral or bilateral breast drainage, which, when examined by microscopy, fails to show fat globules. Gram stain frequently will reveal Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, or Escherichia coli. If the discharge has a greenish tint, Pseudomonas should be suspected. If the discharge is accompanied by abscess formation, drainage as well as antibiotics should be used.

The galactocele, or retention cyst, which usually occurs after cessation of lactation, is caused by duct obstruction and can masquerade as mastitis. These lesions usually lie below the areola and are often tender to palpation. Such cysts occasionally can be emptied by properly placed pressure; however, drainage frequently must be carried out. Untreated galactoceles may be sites of future sepsis and can calcify and become confused with malignant lesions radiologically. The drainage from a galactocele may range from milky to clear to yellow-green purulent-appearing material; however, these lesions are usually sterile.

MAMMARY DYSPLASIAS

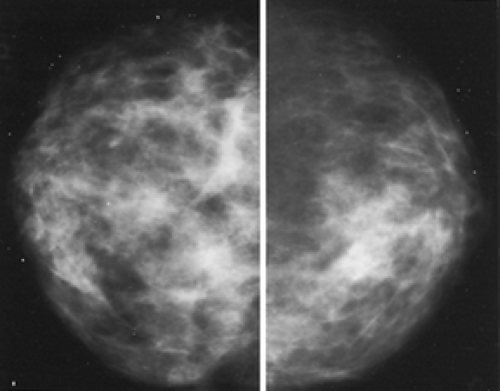

Mammary dysplasia is perhaps the most common lesion of the female breast (Fig. 106-6). Historically, mammary dysplasias have carried the label fibrocystic disease, chronic lobular hyperplasia,

cystic hyperplasia, or chronic cystic mastitis.49 The term cystic mastitis should be discarded, since inflammation is not present in this disorder.

cystic hyperplasia, or chronic cystic mastitis.49 The term cystic mastitis should be discarded, since inflammation is not present in this disorder.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree