clearly documented that low-grade invasive cancers are most often associated with low-grade ductal carcinoma in situ, and high-grade invasive cancers with high-grade in situ lesions (7). In addition, studies evaluating profiles of biological markers and genetic abnormalities have shown that coexisting invasive and in situ carcinomas often share the same immunophenotype and genetic alterations. Gene expression profiling studies have confirmed this observation (8).

TABLE 25-1 Histologic Types of Invasive Breast Cancer in Four Large Series before the Widespread Use of Mammographic Screening | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

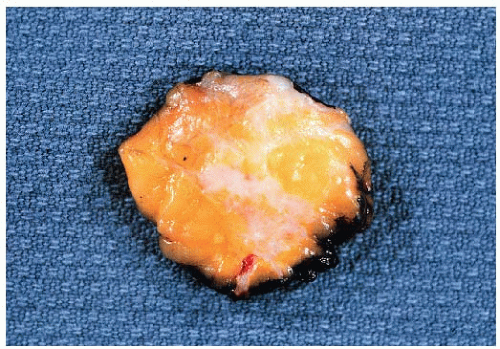

FIGURE 25-1 Cut surface of an excision specimen containing an invasive ductal carcinoma. The tumor appears as an irregular area of whitish tissue. |

highly variable in invasive ductal carcinomas as might be anticipated from their histologic heterogeneity. Although a large number of biomarkers have been studied in invasive ductal carcinomas, only estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and HER2 are reported in routine clinical practice at this time. Overall, 70% to 80% of invasive ductal carcinomas are estrogen receptor positive and approximately 15% are HER2 amplified and overexpressed.

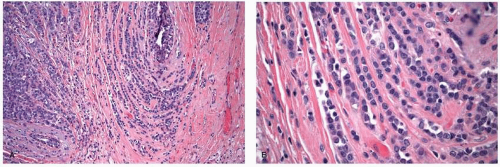

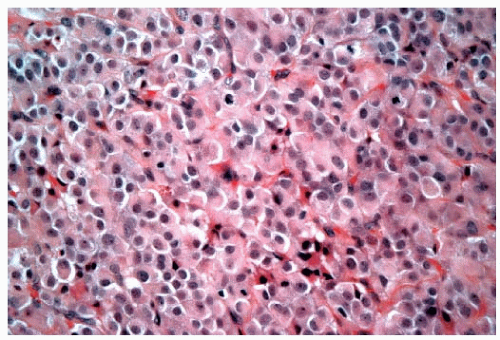

FIGURE 25-2 Invasive ductal carcinoma. (A) Histologic grade 1. (B) Histologic grade 2. (C) Histologic grade 3. |

TABLE 25-2 Histologic Grading System for Invasive Breast Cancers (Elston and Ellis Modification of Bloom and Richardson Grading System) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

criteria. In particular, since the “classical” form of invasive lobular carcinoma was first described by Foote and Stewart (11), a variety of authors have described invasive breast cancers that they consider variants of invasive lobular carcinoma, thereby expanding the spectrum of this histologic type and accounting for a higher incidence of invasive lobular carcinoma in more recent series than in the past. In addition, recent studies have suggested that the increase in the frequency of infiltrating lobular carcinoma may be in part related to the use of postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy (14).

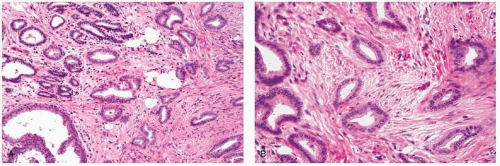

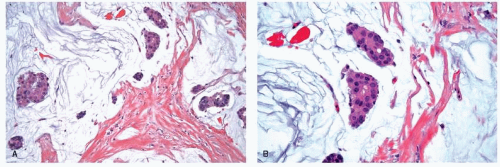

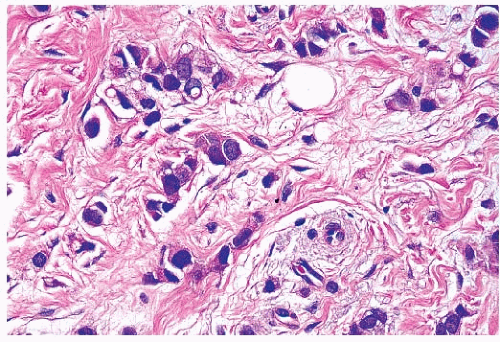

stroma (Fig. 25-4). The alveolar form is characterized by tumor cells that grow in groups of 20 or more cells. These cellular aggregates are separated from one another by a delicate fibrovascular stroma (Fig. 25-5). Although a trabecular variant has also been described (10), there is considerable overlap between this pattern and that seen in the classical form of invasive lobular carcinoma. In the pleomorphic variant, the neoplastic cells are larger, exhibit more nuclear variation than that seen in the classical form, and may show apocrine features (13) (Fig. 25-6). Although signet ring cells can be seen in the classical type of invasive lobular carcinoma as well as in some examples of invasive ductal carcinoma, tumors that are composed of a prominent component of signet ring cells that otherwise have the characteristic features of invasive lobular carcinoma are considered to represent the signet ring cell variant of invasive lobular carcinoma (12). Histiocytoid carcinoma is an apocrine variant of invasive lobular carcinoma in which the tumor cells have a histiocyte-like appearance with abundant foamy pale eosinophilic cytoplasm and mild nuclear atypia (20). Some authors have recognized a “mixed” category of invasive lobular carcinoma. This term is generally used to designate lesions in which no single pattern comprises more than 80% to 85% of the lesion (21).

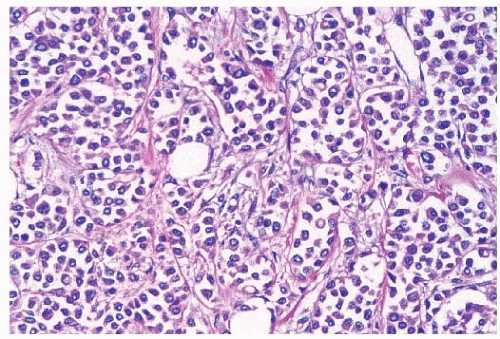

FIGURE 25-4 Invasive lobular carcinoma, solid type. The tumor cells grow in a confluent sheet with little intervening stroma. |

FIGURE 25-5 Invasive lobular carcinoma, alveolar type. Loosely cohesive tumor cell aggregates are separated by delicate fibrous septa. |

FIGURE 25-6 Invasive lobular carcinoma, pleomorphic type. The tumor cells infiltrate the stroma in linear strands, similar to those seen in the classic type of invasive lobular carcinoma. However, the cells in this lobular variant show considerable nuclear pleomorphism, in contrast to the small, monomorphic nuclei characteristic of the classic type of invasive lobular carcinoma (compare with Fig. 25-3B). |

leptomeninges, peritoneal surfaces, retroperitoneum, gastrointestinal tract, and reproductive organs and bone (25). In fact, the majority of cases of carcinomatous meningitis in patients with metastatic breast cancer occur in patients with lobular cancers (98, 26). Peritoneal metastases may appear as numerous small nodules studding the peritoneal surfaces in a manner similar to that seen in ovarian carcinoma (25, 26). Metastases to the stomach can produce an appearance that simulates an infiltrative (linitis plastica) type of primary gastric carcinoma (27). Involvement of the uterus may result in vaginal bleeding (28), whereas metastatic tumor in the ovary may produce ovarian enlargement and the appearance of a Krukenberg tumor.

TABLE 25-3 Frequency of Invasive Lobular Carcinoma Subtypes in Series with More Than 100 Patients | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

experienced significantly greater overall survival at 10 years compared to other patients in a univariate analysis, and “favorable” histology proved to be an independent predictor of survival in node-negative patients by multivariate analysis (43). Similar improved survival rates in patients with tubular carcinoma were reported in a series of 1,621 patients, although these patients were not stratified by node status (6). In this latter study, even patients with “tubular mixed” tumors (which were defined as stellate cancers composed of cells typical of invasive ductal carcinoma but with central tubules identical to tubular carcinoma) experienced significantly better overall survival compared to patients with invasive ductal carcinoma (6). In addition, two series, one examining node-negative early stage breast cancer patients treated with mastectomy, and the other examining early stage patients treated with breast-conserving therapy, both reported that patients with tubular carcinoma had significantly lower rates of distant recurrences compared to patients with invasive ductal carcinoma (41, 42).

include mucocele-like lesions, benign lesions characterized by cystically dilated ducts associated with rupture and extravasation of mucin into the stroma. Type B mucinous carcinomas may show endocrine differentiation, including immunoreactivity for chromogranin or synaptophysin (48). Mucinous carcinomas are often accompanied by a DCIS component which may have a papillary, micropapillary, cribriform, or solid pattern. In some cases, the DCIS may also exhibit prominent extracellular mucin production (47).

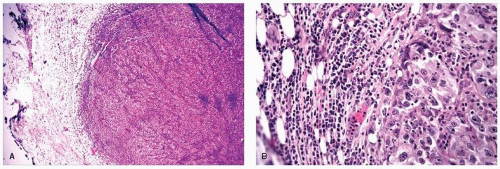

the available data suggest that conservative surgery and radiation therapy is appropriate local treatment for patients with medullary carcinoma and carcinoma with medullary features.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree