Fig. 4.1

Gross specimen showing a white pearly irregular tumor with pale yellow gritty areas likely corresponding to comedo necrosis

Classic histologic features of DCIS include cohesive, clonal-appearing epithelial cells with prominent cell borders (Fig. 4.2). However, DCIS has significant histologic heterogeneity, with a wide spectrum of architectural and cellular patterns including comedo, cribriform, solid, papillary, micropapillary, clinging, apocrine, and clear-cell types (Fig. 4.3a–h). Histologic grade of DCIS also has significant variability and although there have been many proposed grading systems for DCIS [22–31], consensus committee guidelines [32] have supported reporting of nuclear grade as low, intermediate, or high (Fig. 4.4a–c) as well as documenting of the presence of necrosis, cell polarization, and prominent architectural pattern(s). The most salient histological features of low, intermediate, and high-grade DCIS are described below.

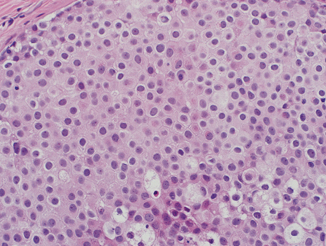

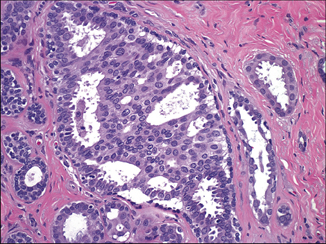

Fig. 4.2

Ductal carcinoma in situ with cohesive, moderately enlarged, monotonous epithelial cells with evident nucleoli and prominent cell borders (H&E, 40×)

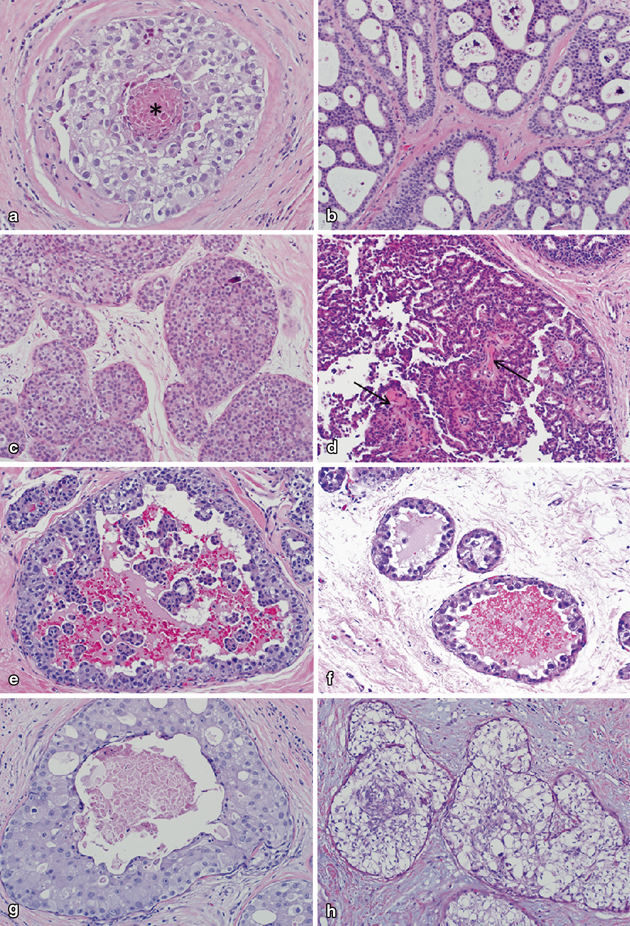

Fig. 4.3

Various architectural patterns of ductal carcinoma in situ. a Comedonecrosis pattern with punctate central necrosis (indicated by *). b Cribriform pattern with numerous round, “punched out” microlumina. In this case, lumina contain abundant purple-staining microcalcifications. c Solid pattern with complete filling of involved glands. A single, small, purple-staining microcalcification is present in the upper right. d Papillary pattern in which DCIS cells line prominent fibrovascular cores (denoted by arrows). e Micropapillary pattern with tufts and fronds of DCIS cells protruding into the central duct lumen. f Clinging pattern with DCIS cells lining the basement membrane. As seen in this case, clinging pattern DCIS cells often have prominent luminal cytoplasmic tufts or “snouts.” g Apocrine pattern in which DCIS cells have prominent nucleoli and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm. h Clear-cell pattern with cytoplasmic clearing (a–h; H&E, 20×)

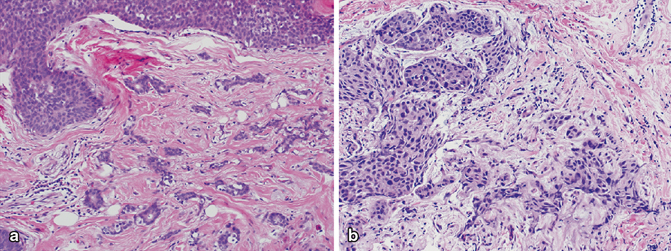

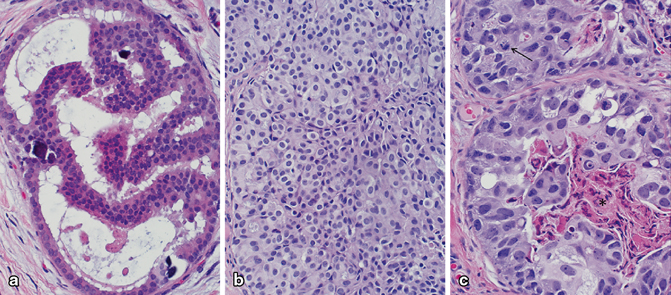

Fig. 4.4

Spectrum of nuclear grade in ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). a Low nuclear grade DCIS with small, uniform, monotonous nuclei. b Intermediate nuclear grade DCIS with moderate enlargement and pleomorphism. c High nuclear grade DCIS with marked enlargement and pleomorphism. Comedonecrosis (denoted by *) and numerous mitotic figures (denoted by arrow) are often present in high-grade DCIS as seen in this case (a–c; H&E, 40×)

Low-Grade DCIS

Low-grade DCIS is characterized by the growth of small, fairly monotonous cells respecting each other’s cell borders. The nuclei are often hyperchromatic and uniform, with inconspicuous nucleoli. The cytoplasm is usually scant, with a slight increase in the nuclear–cytoplasmic ratio. Mitoses are infrequent, but when present, aid in the diagnosis.

Low-grade DCIS may exhibit a variety of architectural patterns of which the most frequent are micropapillary, cribriform, and solid. Micropapillary low-grade DCIS is composed of rounded tufts of neoplastic cells that project into the duct lumen without fibrovascular cores. The cells forming the micropapillae are typically evenly distributed and are uniform with dark nuclei and a monotonous appearance (Fig. 4.5). The cribriform pattern of low-grade DCIS is characterized by neoplastic cells forming round and rigid secondary lumens. These spaces are frequently calcified. While necrosis is rare in low-grade DCIS, it may be observed in some cases .

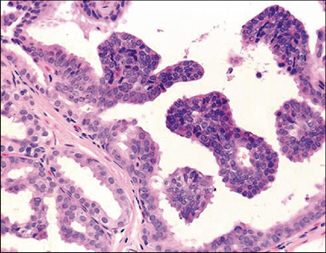

Fig. 4.5

Low-grade ductal carcinoma in situ with micropapillary pattern. The neoplastic cells are monotonous and form rounded micropapillae lacking fibrovascular cores that project into the ductal lumens (H&E, 40×)

Micropapillary low-grade DCIS is frequently multicentric, and most of these patients accordingly have extensive microcalcifications on imaging. Not surprisingly, despite the low-grade features, micropapillary DCIS is nevertheless a risk factor for recurrence in patients treated with lumpectomy. The ducts with tumor are often admixed with benign or atypical ducts. Hence, diagnosis can be a challenge, especially in core biopsies.

Stringent criteria need to be used to diagnose micropapillary low-grade DCIS. These include: (a) micropapillae are club like and involve the entire duct circumference, extend at least one third of the duct diameter, and show a tendency to detach, (b) the nuclei are not overlapping, and (c) at least three adjacent ducts must be fully involved .

Intermediate Grade DCIS

While the architectural patterns of intermediate grade DCIS are similar to low-grade lesions, intermediate-grade DCIS is characterized by slightly increased cellular pleomorphism, more frequent prominent nucleoli, and coarser chromatin than low-grade DCIS (Fig. 4.2) . Mitoses and necrosis are also more frequently encountered in intermediate-grade DCIS compared to low-grade lesions.

High-Grade DCIS

High-grade DCIS is defined by marked nuclear enlargement and pleomorphism . The nuclei have coarse chromatin and prominent nucleoli. There is loss of cell polarity and mitoses are frequent and often atypical. The comedo-type necrosis architectural pattern is very common, but solid, cribriform, micropapillary, and clinging patterns are also often seen. Central comedonecrosis is often accompanied by calcifications, which may be large and amorphous (Fig. 4.6). High-grade DCIS is also frequently associated with periductal chronic inflammation (Fig. 4.7) and angiogenesis, and a desmoplastic or sclerotic stromal response, with both concentric and distorting patterns (Fig. 4.8a–c).

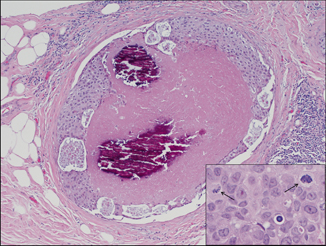

Fig. 4.6

High-grade ductal carcinoma in situ with comedonecrosis and large, amorphous calcifications (H&E, 10×); inset shows large, pleomorphic cells with readily identifiable mitotic forms (denoted by arrow; H&E, 40×)

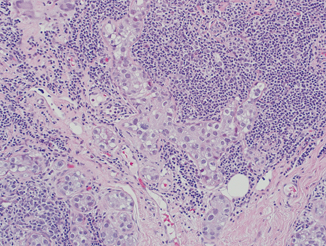

Fig. 4.7

High-grade ductal carcinoma in situ with cancerization of lobules and marked periglandular chronic inflammation (H&E, 20×)

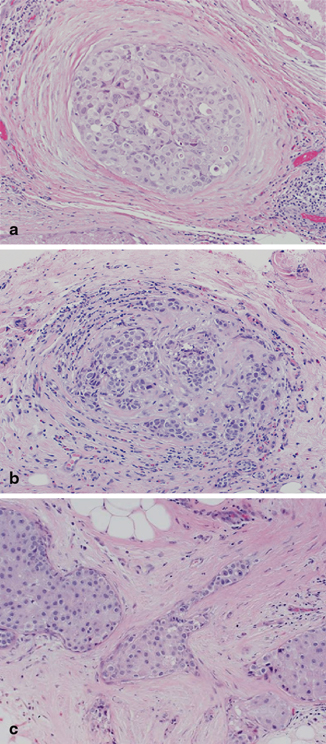

Fig. 4.8

Variable sclerosis associated with high-grade ductal carcinoma in situ, ranging from a concentric, b mixed concentric and distorting, and c markedly distorting (a–c; H&E, 20×)

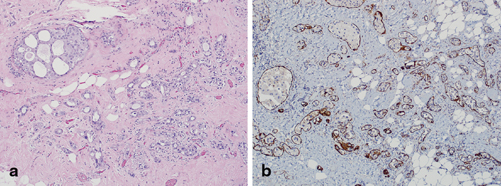

High-grade DCIS may sometimes mimic microinvasive carcinoma , especially when DCIS extends into small glands of lobules that are distorted by marked sclerosis or secondarily involve sclerosing adenosis, radial scars, or complex sclerosing lesions. In such cases, deeper sections and immunohistochemical (IHC) stains that highlight myoepithelium, such as p63, calponin, muscle-specific or smooth muscle actin, among others, may be helpful in assessing the presence of microinvasion. The use of myoepithelial stains is particularly helpful if DCIS extends into sclerosing lesions such as sclerosing adenosis, which is rich in myoepithelial cells (Fig. 4.9a, b). However, staining for myoepithelial markers may not always aid in the differentiation between DCIS and microinvasive carcinoma, as staining may be patchy and difficult to interpret or the small focus may be mostly or completely lost in deeper immunostained slides. In such cases, the suspicion for a focus of microinvasion should be stated in the pathology report .

Fig. 4.9

a Apocrine ductal carcinoma in situ involving sclerosing adenosis (H&E, 10×) and b corresponding immunohistochemical (IHC) stain for muscle-specific actin which highlights myoepithelium throughout, confirming in situ disease only (IHC, 10×)

Biomarkers and Molecular Pathology

Consonant with the histological heterogeneity, DCIS exhibits significant variability in biomarker profiles and genetic aberrations . Low nuclear grade DCIS almost universally has diffuse, strong expression of estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) and lacks HER-2/neu protein overexpression or gene amplification. In contrast, high nuclear grade DCIS can be ER/PR positive or negative and is HER-2/neu positive in 60–80 % of cases (Fig. 4.10a–h) [33–36]. Unlike low-grade DCIS, high-grade DCIS also has high proliferative rates and is often p53 positive by IHC and mutational analyses [29, 37]. Molecular studies have shown that low-grade DCIS is characterized by chromosomal losses at 16q and 17p and gains at 1q, whereas high-grade DCIS shows more numerous and variable alterations, including losses at 11q, 14q, 8p, and 13q and gains at 17q, 8q, and 5p [38, 39] .

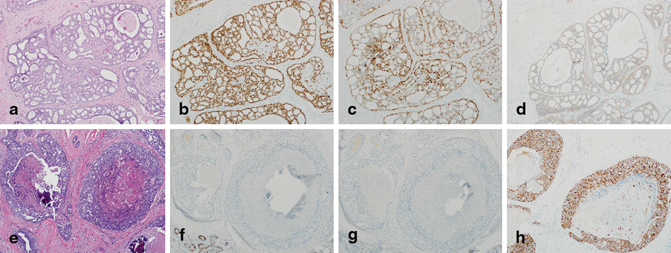

Fig. 4.10

a Low nuclear grade ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS; H&E, 10×) that is b estrogen receptor (ER) positive, c progesterone receptor (PR) positive, and d HER-2/neu (1+) negative for overexpression by immunohistochemical (IHC) staining (b, d; IHC, 10×). e High nuclear grade DCIS (H&E, 10×) that is f ER negative (with positive staining in benign glands in the lower left-hand corner), g PR negative, and h HER-2/neu (3+) positive for overexpression (f–h; IHC, 10×)

Morphologic, immunophenotypic, and molecular evidences support that DCIS represents a heterogeneous group of diseases that differ in biologic potential, ranging from little-to-no to very high risk of progression to invasive carcinoma. Due to its diversity and in attempt to avoid the anxiety-producing word “carcinoma” in its name, some support renaming DCIS as ductal intraepithelial neoplasia (DIN) as proposed by Tavassoli et al. [30], which is similar nomenclature to that used to describe dysplasias of the genital tract and perineum. Further study is necessary to determine whether DCIS should be further subclassified and/or redefined based on grade, hormone receptor status or other remarkable histological features .

Differential Diagnosis of DCIS Relevant to Clinical Practice

Atypical ductal hyperplasia . The main differential diagnosis of low-grade DCIS is with atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH). ADH is characterized by one or two moderately distended ducts, filled by cells that are evenly spaced, having uniform nuclei, and some regular secondary lumens (Fig. 4.11). Importantly, ADH lacks pleomorphism, individual cell necrosis, frequent mitoses, or prominence of nucleoli, which characterize DCIS. The presence of cells that overlap and stream, features more in keeping with benign usual ductal hyperplasia, mixed with atypical cells is a helpful feature to distinguish ADH from DCIS.

Fig. 4.11

Atypical ductal hyperplasia showing a group of atypical pleomorphic cells mixed in with bland, overlapping, and streaming epithelial cells (H&E, 40×)

It is common to observe a spectrum of disease in the same breast that ranges from ADH to DCIS. Thus, borderline cases may be seen at either the low end or high ends of the spectrum. At times, the distinction between ADH and low-grade DCIS is one of the most challenging diagnostic difficulties in breast pathology. Most experts would assign these challenging cases to the less severe diagnostic category. Interestingly, most ADH is detected in the vicinity of—or within—a sclerosing lesion, a papilloma and—especially—within or close to a worrisome columnar altered lobule. ADH is often near the targeted calcifications in a biopsy.

Pleomorphic lobular carcinoma in situ . Pleomorphic lobular carcinoma in situ (pLCIS) has morphologic features of both classic LCIS and high-grade DCIS. Like classic LCIS, the cells are discohesive and have prominent plasmacytoid morphology. However, the cells of pLCIS are also enlarged and have marked nuclear pleomorphism and readily identifiable mitotic activity as seen in high-grade DCIS. pLCIS may also have comedo-type necrosis, a common architectural pattern of high-grade DCIS. pLCIS has been further divided into non-apocrine and apocrine types, the latter of which has apocrine features including prominent nucleoli and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm (Fig. 4.12) .

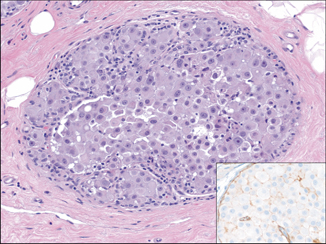

Fig. 4.12

Pleomorphic lobular carcinoma in situ (pLCIS), apocrine type. pLCIS cells are discohesive with plasmacytoid morphology and intracytoplasmic lumina but have moderate-marked enlargement and pleomorphism. Apocrine features including prominent nucleoli and abundant eosinophic cytoplasm are present. The inset shows the corresponding E-cadherin immunohistochemical (IHC) stain demonstrating lack of staining in the neoplastic cells, supporting lobular differentiation (H&E and IHC, 20×)

pLCIS demonstrates loss of E-cadherin expression and chromosomal losses at 16q and 17p and gains of 1q, which are hallmark features of classic invasive and in situ lobular carcinomas [40, 41]. However, compared to classic LCIS which is invariably ER/PR positive and HER-2/neu negative, pLCIS has lower levels and is less frequently ER positive and may be HER-2/neu positive in approximately 25 % of cases [42]. pLCIS also has been shown to have additional genetic aberrations including deletion of 8p and 13q and gains of 8q, which were also identified in matched pleomorphic invasive lobular carcinoma (pILC) [40, 41, 43]. However, Chen et al. [44] found that apocrine pLCIS had greater numbers and diversity of genetic abnormalities than non-apocrine pLCIS, which had a similar profile to classic LCIS. Specifically, they identified amplification at 17p11.2–17q12 and 11.q.13.3, gain of 16p and losses of 3q, 11q, 13q, and 17p in the apocrine pLCIS group .

Classic LCIS is generally regarded as a marker of bilateral future cancer risk. In contrast, pLCIS has higher-grade morphology, an often unfavorable biomarker profile and greater extent of genetic aberrations, and thus is thought to be a non-obligate precursor of pILC [45]. Therefore, pLCIS is treated similar to DCIS, with excision to histologically negative margins and eradication of all suspicious mammographic calcifications. However, use of adjuvant radiation for pLCIS is controversial with many advocating it but with little data to support its use.

pLCIS is a morphologically and genetically distinct entity but may be misinterpreted as high-grade DCIS, especially if it is the apocrine subtype. Current practice is, treatment in a similar manner to DCIS, thus misclassification may have little detrimental effect to the patient. However, correct classification may influence decision for adjuvant radiation therapy. Furthermore, correct classification will aid in identifying cases for future study to better understand how pLCIS differs from classic LCIS and high-grade DCIS .

Microinvasive carcinoma

Microinvasive carcinoma is invasive carcinoma that has unequivocal infiltration beyond the glandular basement membrane but has no focus of invasion greater than 0.1 cm in size (T1mic) [46]. Microinvasive carcinoma cells may infiltrate as small clusters, tubules, or as single cells. Performance of IHC stains to show lack of staining with myoepithelial markers may be necessary to prove a morphologic suspicion of microinvasion .

Microinvasive carcinoma often occurs in the setting of abundant DCIS. Therefore, it is extremely important to thoroughly sample excision specimens for microscopic evaluation if there is a prior biopsy diagnosis of DCIS only, especially, if there is radiologic or gross evidence of multifocal or mass-forming disease. Microinvasive carcinoma more often arises in the setting of high-grade DCIS but may also be seen in association with low-grade DCIS (Fig. 4.13a–b). Coexisting microinvasive carcinoma and DCIS components very frequently have similar morphologic features and ER, PR, and HER-2/neu staining patterns.