in breasts with cancer was compared with their prevalence in breasts without cancer (1). While these studies demonstrated that some benign lesions are more common in cancer-containing breasts, the histologic coexistence of certain benign breast lesions with breast cancer is not sufficient to establish that those benign lesions impart an increased cancer risk.

TABLE 9-1 Categorization of Benign Breast Lesions According to the Criteria of Dupont, Page, and Rogers (3) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

TABLE 9-2 Relative Risk of Breast Cancer According to Histologic Criteria of Benign Breast Disease in Four Studies Using the Criteria of Dupont, Page, and Rogers (3) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

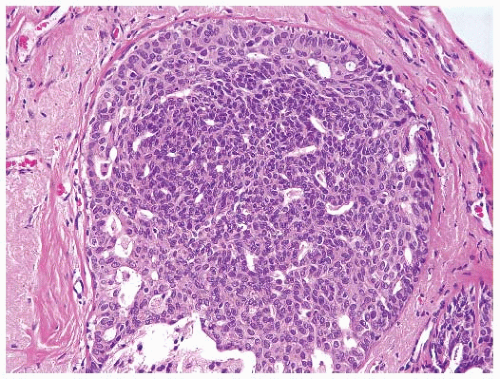

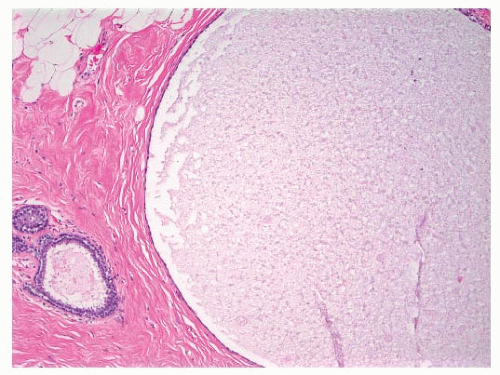

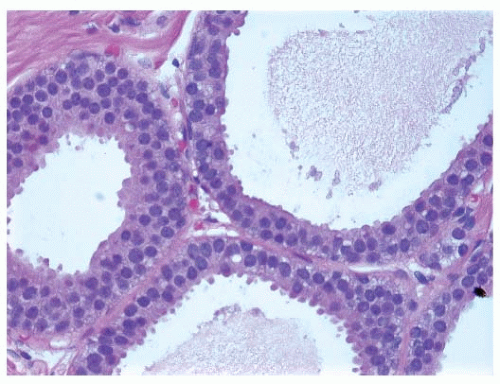

FIGURE 9-1 Cyst characterized by a large, dilated space filled with secretory material and lined by a flattened epithelial cell layer. |

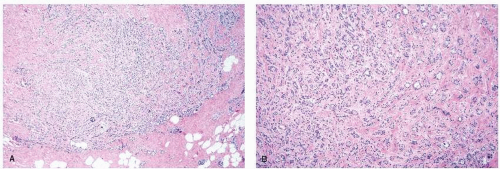

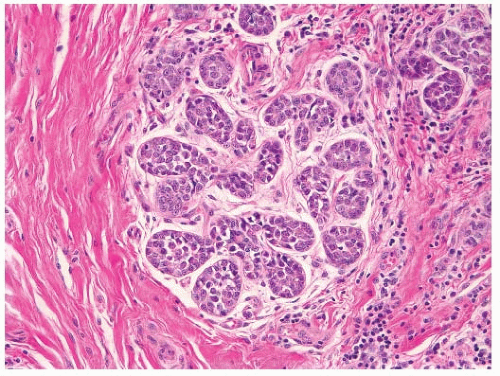

or lobular type (3, 7). Atypical ductal hyperplasias (ADH) are lesions that have some of the architectural and cytologic features of low-grade DCIS, such as nuclear monomorphism, regular cell placement, and round regular spaces, in at least part of the involved space. The cells may form tufts, micropapillations, arcades, bridges, solid, and cribriform patterns (11). A second cell population with features similar to those seen in usual ductal hyperplasia is also typically present (Fig. 9-4).

not (16) (Table 9-3); at the present time this issue remains unresolved. Patients whose biopsies showed ALH involving both lobules and ducts had a higher relative risk of developing cancer (RR 6.8) than those with either ALH alone (RR 4.3) or those with only ductal involvement by atypical lobular hyperplasia (RR 2.1) (14).

TABLE 9-3 Relative Risk of Breast Cancer According to Type of Atypical Hyperplasia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

lesions without atypia who remained free of breast cancer for 10 years after their benign breast biopsy were at no greater breast cancer risk than women of similar age without such a history. In addition, the breast cancer risk among women with atypical hyperplasia was greatest in the first 10 years after the benign breast biopsy (RR 9.8) and fell to a relative risk of 3.6 after 10 years (18). In contrast, in an analysis of data from the Nurses’ Health Study, the breast cancer risk among women with proliferative lesions without atypia was similarly elevated before and after 10 years following the benign breast biopsy (RR 1.4 and 1.6, respectively). In addition, the risk associated with atypical hyperplasia was higher after 10 years (RR 5.2) than in the first 10 years after the benign breast biopsy (RR 3.3) (2). Similarly, in the Mayo Clinic study, an excess breast cancer risk was seen among women with biopsy-proven benign breast disease for at least 25 years after the benign breast biopsy (5). Among patients with atypical hyperplasia, the relative risk was persistently elevated beyond 15 years (16). More data are needed to clarify further the relationship between time since biopsy and breast cancer risk for women with benign breast disease, particularly for women with atypical hyperplasia.

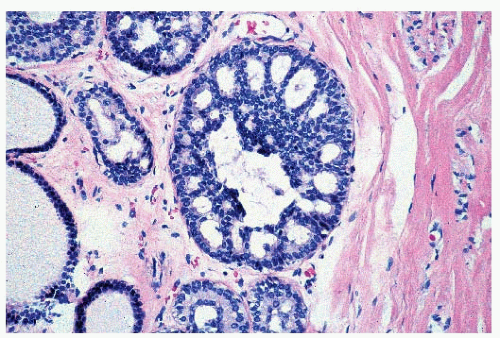

FIGURE 9-6 Flat epithelia atypia. The normal epithelial cells in the acini of this terminal duct are replaced by a population of columnar epithelial cells with round, monomorphic nuclei. |

TABLE 9-4 Effect of Family History of Breast Cancer on Relative Risk of Breast Cancer | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree