Pathologic Fractures

Timothy A. Damron

A pathologic fracture is defined as one occurring in abnormal bone. The abnormality in the bone may be due to metabolic diseases (such as osteoporosis, osteomalacia, or Paget’s disease), benign lesions, sarcomas, lymphoma, metastatic disease, and myeloma. This section focuses on management of pathologic fractures in bone sarcomas and in disseminated malignancy (metastatic disease and myeloma).

Diagnostic Work-Up

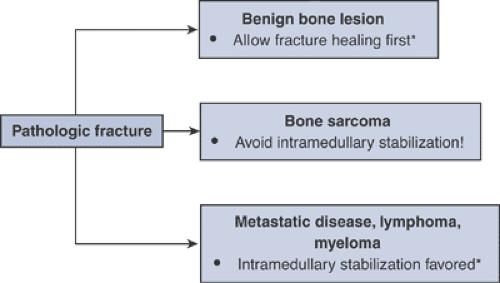

Because treatment differs according to diagnosis, the underlying diagnosis should be established prior to embarking on a treatment plan (Algorithm 4.5-1). The most serious mistake one can make is to assume that a pathologic fracture is due to a disseminated malignancy only to find out after the surgical procedure that the actual diagnosis is that of a bone sarcoma.

The work-up of an aggressive-appearing bone lesion suspected of being due to disseminated malignancy is detailed in Chapter 8, Metastatic Disease. Other than for some benign bone lesions and very carefully selected cases of widely disseminated metastatic disease, biopsy is often necessary to establish the diagnosis.

General Principles of Work-up

Presence of a fracture should not preclude an adequate preoperative work-up.

Many benign bone lesions can be managed without biopsy initially, allowing healing of fracture if specific criteria are met:

No pain preceding fracture

Pain preceding fracture should elicit concern for active or aggressive lesion, and biopsy should be considered.

Recognizable radiographic features of an indolent lesion

Nonossifying fibroma

Unicameral bone cyst

Enchondroma

Proximal femoral benign lesions with displaced pathologic fractures heal with malunion if not treated operatively.

Intramedullary reamings are not a good source of biopsy material.

Await final frozen section diagnosis before proceeding with operative intervention.

Pathologic Fractures in Bone Sarcomas

Pathologic fractures through bone sarcomas present the clinician with two difficult decisions. First, initial fracture management must be carefully executed to minimize complications and, in the case of high-grade sarcomas, to allow completion of neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Second, since pathologic fracture has been associated with a poorer overall prognosis, a decision must be made between amputation and limb-sparing surgery, taking into account the associated fracture and its initial treatment.

Table 4.5-1 Alternatives for Initial Management of Pathologic Fracture Through Bone Sarcoma | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Initial Bone Sarcoma Pathologic Fracture Management (Table 4.5-1)

Goals

Minimize tumor contamination of uninvolved areas

Avoid spreading tumor proximally and distally within intramedullary canal.

Avoid exposure of vital neurovascular structures to tumor.

Avoid spreading tumor to uninvolved muscle compartments.

Avoid loading pulmonary vasculature with tumor-laden reamings.

Allow completion of neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

Approaches

Preferred: casting or traction

Less viable alternatives

Spanning external fixation

Limited internal fixation with plate/screws

Contraindicated: intramedullary stabilization

Contaminates uninvolved proximal and distal bone, soft tissues

Reamings may disseminate tumor into pulmonary vasculature.

Limb-Sparing Versus Amputation for Bone Sarcoma Pathologic Fracture

Theoretical Concerns

Fracture hematoma increases local tumor dissemination.

Difficulty predicting extent of tumor

Consequent increased risk for local recurrence

More difficult to manage resection intraoperatively, particularly with unstable fracture or deformity

Consequent increased risk of tumor spillage or positive margin

Outcome

With adjuvant chemotherapy, osteosarcoma and Ewing sarcoma oncologic survival outcome equivalent between amputation and limb-sparing surgery

Pathologic Fractures in Disseminated Malignancy

The goals of treatment for patients with disseminated malignancies, including metastatic disease, myeloma, and lymphoma, are to relieve pain, preserve function, and maintain independence. These goals may be accomplished by means of surgery, bracing, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, bisphosphonates, or a combination. Consideration for nonorthopaedic care should be given in consultation with medical and/or radiation oncologists. Medical oncologists should be consulted to estimate expected survival.

Surgical Principles

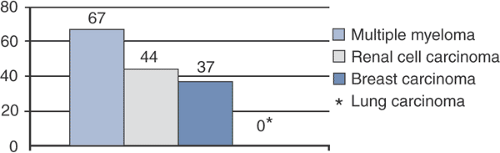

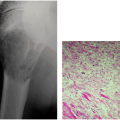

Surgical principles are summarized in Table 4.5-2. Figure 4.5-1 summarizes the healing rates associated with pathologic fractures based on underlying disease.

Preoperative Planning

X-rays of entire long bones and adjacent joints should be obtained to evaluate for other lesions.

Consider complete staging to assess for extent of disease.

Extent influences the prognosis, which should be considered prior to operative intervention.

Impending pathologic fractures may become apparent in other bones.

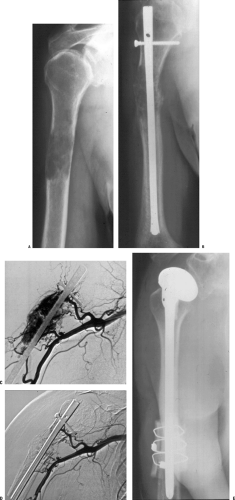

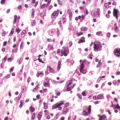

Consider preoperative embolization for renal cell metastases due to their high propensity for intraoperative hemorrhage (Fig. 4.5-2).

Table 4.5-2 Surgical Principles for Pathologic Fractures Due to Disseminated Malignancy | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Complications Unique to Metastatic Disease Pathologic Fracture Fixation

Disease recurrence

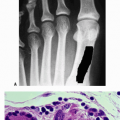

Radiosensitive tumors are less likely to recur locally following postoperative irradiation (especially breast cancer, myeloma; Fig. 4.5-3).

Relatively radioresistant tumors must be watched closely (especially renal cell carcinoma; see Fig. 4.5-2).

Failure of fixation

Tumors with higher potential to heal fractures are less likely to incur fixation failure (e.g., myeloma; see Fig. 4.5-1).

Tumors with lower potential to heal fractures are more likely to incur fixation failure (e.g., lung carcinoma), but patients may not live long enough to have a problem.

Postoperative Management

Goal should be to allow full weight bearing immediately postoperatively.

Importance of postoperative radiotherapy

Lower chance of disease recurrence

Lower chance of hardware failure and need for second operative intervention

Better functional outcome

Surgical and Nonoperative Options

Femur

Proximal femur

Femoral neck

Long-stem cemented hemiarthroplasty is the gold standard for both impending fractures and after the fact.

Long stem is absolutely indicated when there are distal shaft lesions, as these lesions serve as stress risers and may progress. The long stem protects the remainder of the femur.

Cementing provides immediate stability.

Hemiarthroplasty is inherently more stable than total hip arthroplasty.

Total hip arthroplasty is not needed unless there is a significant acetabular lesion that requires operative fixation (see acetabular section).

Potential complications

Embolization has been reported, sometimes with catastrophic consequences, so adequate precementing hydration, oxygenation, canal lavage, and consideration of venting should be done.

Occult penetration of the femoral cortex by guide rods, reamers, broaches, and/or femoral stems may occur through unrecognized distal lesions.

Intertrochanteric region (Figs. 4.5-4 to 4.5-6)

Surgical options: Depend on extent of destruction, adequacy of proximal femoral bone to accept internal fixation (Table 4.5-3)

Subtrochanteric region

Gold standard is the proximally and distally locked intramedullary reconstruction nail.

Bone cement is absolutely indicated only if screw fixation is inadequate or when segmental destruction creates loss of femoral continuity, but bone cement can be used at the surgeon’s discretion.

When subtrochanteric lesions extend proximally to the point that inadequate fixation will be achieved with an intramedullary nail, a proximal femoral replacement long-stem cemented endoprosthetic hemiarthroplasty should be considered.

Femoral diaphysis

Gold standard is the proximally and distally locked intramedullary reconstruction nail. (Fig. 4.5-7).

Rationale: Proximal prophylactic fixation of the neck region protects a common site of femoral metastases, where a standard intramedullary nail would leave the femoral neck unprotected.

Distal femur

Surgical options: Depend on exact location of lesion, extent of destruction (Table 4.5-4)

Distal femoral plate and screw options are dictated by availability of distal bone.

Dynamic condylar screw requires approximately 5 cm of intact distal bone.

Distal femoral blade plate requires approximately 3 cm of intact distal bone.

Condylar buttress plates, particularly newer locking condylar plates, are necessary for severely compromised distal bone with less intact bone or partially compromised distal bone; these plates are generally preferred for pathologic distal femur fractures.

Bone cement is generally indicated as an adjunct to these fixation options.

Pelvis

Nonacetabular (ilium, pubic ramus)

Nonoperative care: observation, irradiation

Operative care: usually not indicated

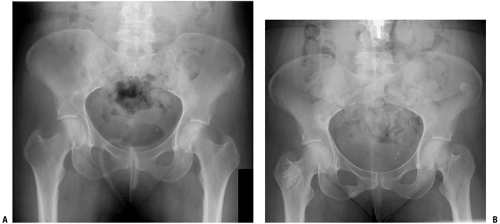

Acetabulum (Table 4.5-5 and Fig. 4.5-8)

Humerus

Proximal humerus

Nonoperative treatment: Sarmiento-type fracture brace with proximal Galveston extension, irradiation

Prophylactic stabilization and fracture fixation depend upon location and extent of bone destruction (Table 4.5-6 and Fig. 4.5-9).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree