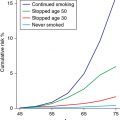

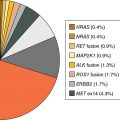

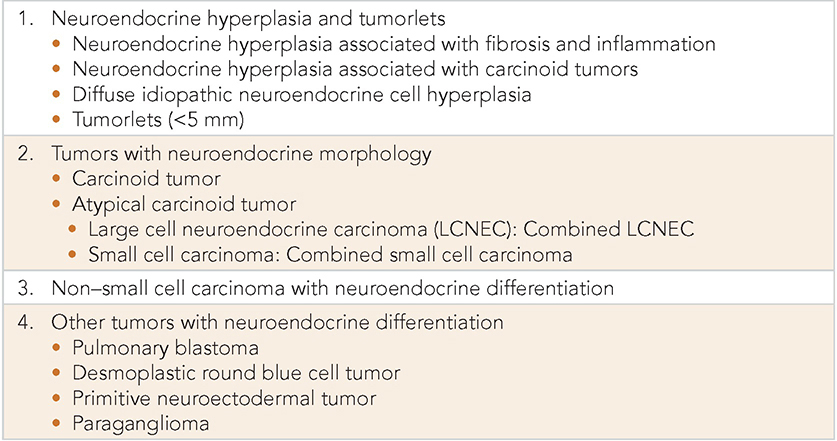

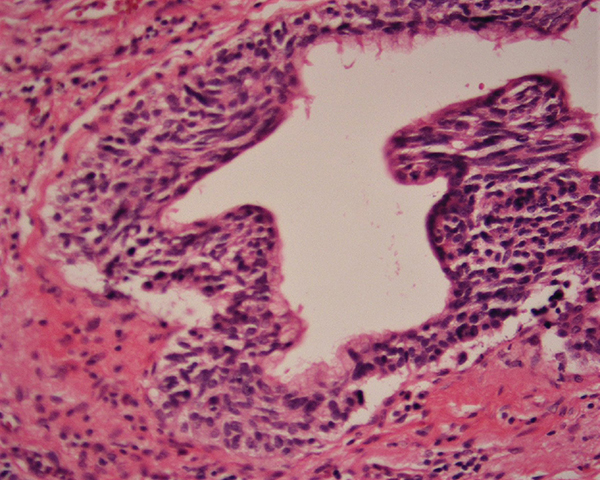

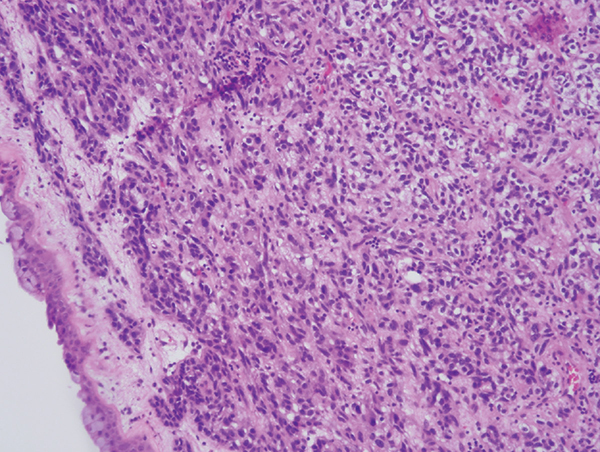

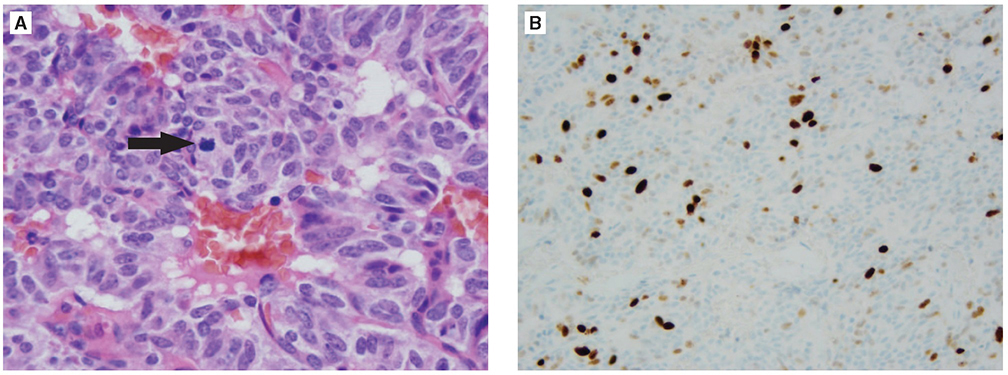

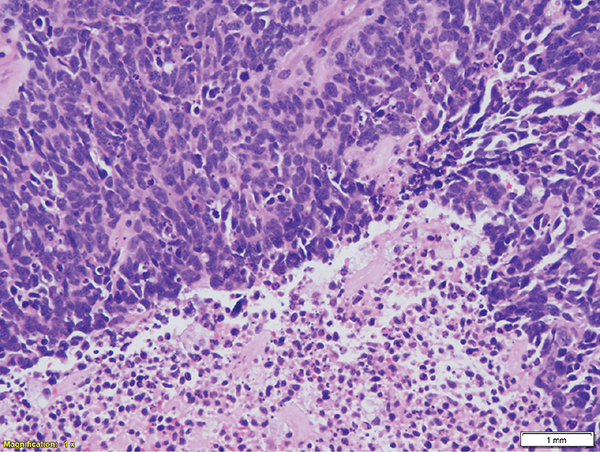

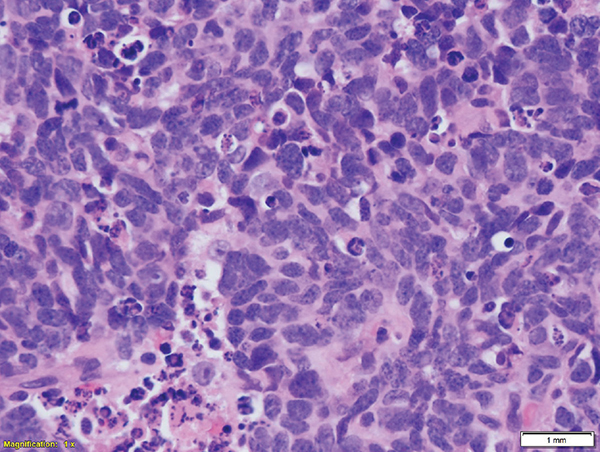

A 60-year-old white male had a 6-cm central lung mass biopsied by core needle biopsy. He smoked two packs of cigarettes per day for 40 years and has had a coronary stent placed. The magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain shows 2 subcentimeter metastases. A positron emission tomographic (PET) scan shows a liver mass and rib lesions. His serology shows a sodium level of 120 mEq/L. Learning Objectives: 1. What is the new World Health Organization (WHO) classification for small cell lung cancer? 2. What are the markers distinguishing small cell from non–small cell lung cancer? 3. What are the types of neuroendocrine tumors found in the lung? Recognition of the distinct biological behavior of small cell carcinoma from that of non–small cell carcinoma has been long established. Therefore, the characterization of small cell carcinoma has proven to be very important as it has therapeutic as well as prognostic implications. However, the presence of other tumors with overlapping morphological, ultrastructural, and immunohistochemical features has complicated this endeavor. The spectrum of preinvasive neuroendocrine lesions encompasses conditions of several associations and clinical presentations. However, the histomorphologic features are mostly similar with only a few distinguishing features. There are conditions that are associated with neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia but the mechanism of action is poorly understood. The chronic conditions of inflammation and fibrosis as in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease have a tendency to harbor small foci of neuroendocrine proliferation. These are usually incidental findings encountered when the lung is sampled for other reasons. In resections for carcinoid tumors, other foci of neuroendocrine proliferation are present and could represent a “field defect” similar to that of atypical adenomatous hyperplasia (AAH) and adenocarcinoma. The spectrum of neuroendocrine tumors in their progressive pattern is outlined (Table 7-1). TABLE 7-1 Neuroendocrine Proliferations and Tumors of the Lung Diffuse idiopathic neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia is an uncommon condition in which the airways are circumferentially involved by a proliferation of neuroendocrine cells underneath the bronchial epithelium (Figure 7-1). The origin of these cells is believed to be from Kulchitsky cells, which normally reside as individual cells in this location. In about half of the patients, the neuroendocrine hyperplasia could present in the setting of an interstitial lung disease investigation based on peribronchial fibrosis and inflammation in addition to neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia. In the other half of the patients, it is usually an incidental finding in the course of investigating extrapulmonary malignancies with potential metastasis to the lung.1 They have a distinctive CT presentation, with pulmonary nodules and centrilobular and peribronchial nodules corresponding to carcinoid tumorlets and carcinoid tumors, respectively.2 Figure 7-1. Diffuse idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia (DIPNECH) has a peribronchial pattern with hyperchromatic nuclei and a small amount of cytoplasm compared with the overlying layer of bronchial epithelium. Because of the coexistence of DIPNECH with carcinoid tumorlets, and the lesions are usually multiple, this led to the belief that they are closely related and represent part of the spectrum in the evolution of other neuroendocrine tumors. DIPNECH present as a layer of darker, more compact cells than those of the overlying bronchial epithelium. They are immunoreactive to the common neuroendocrine markers, such as synaptophysin, chromogranin A, and CD56. Carcinoid tumorlets are usually present as nests of neuroendocrine cells separated by the surrounding connective tissue stroma in the peribronchial area. The cells have uniform nuclei with salt-and-pepper chromatin, absent or inconspicuous nucleoli, and granular amphophilic cytoplasm. Mitotic figures are extremely rare, and no necrosis is noted. The overall dimension of the lesion should be less than 5 mm; anything beyond this dimension with the same morphology is considered as a typical carcinoid tumor. Carcinoid tumors account for 1%-2% of all invasive lung malignancies. In about half of the cases, the patients are asymptomatic, and the lesions are discovered incidentally in the course of workup of other conditions. In the other half, nonspecific symptoms such as hemoptysis, postobstructive pneumonia, or dyspnea may manifest themselves. The average age of patients is between 45 and 55 years, but the tumors could occur at any age. They are the most common lung tumors of childhood. They could be associated with a paraneoplastic syndrome, with the most common type Cushing syndrome. The tumor location is usually central with a well-circumscribed or lobulated outline. The tumors could also be peripheral, under the pleural surface. The tumors usually show low uptake by PET scans. A microscopically typical carcinoid tumor is characterized by an organoid pattern, with tumor cells organized in nests, strips, festoons, papillary, mucinous, or signet ring and pseudoglandular patterns separated by either a delicate or sclerotic stroma. Some tumors could assume enough of spindle cell morphology to be confused with benign or well-differentiated mesenchymal tumors. There is usually peripheral palisading of the nuclei and the presence of rosettes contributes to the organoid pattern. The nuclei are uniform with absent or inconspicuous nucleoli. The chromatin is evenly distributed and could be powdery, imparting the salt-and-pepper quality characteristic of neuroendocrine cells in general. The cytoplasm is faintly granular and amphophilic with a fair amount surrounding the nuclei. The mitotic activity is very low, with less than 2 mitoses per 2 mm2 (equal to 10 high-power fields in some microscopes) (Figure 7-2). In between 5% and 20% of cases, metastasis to local lymph nodes could occur; however, this should not be used as a criterion for atypical carcinoid (Table 7-1). The treatment of choice is usually surgical resection, with excellent prognosis. Patients rarely die of typical carcinoid tumors. Figure 7-2. Carcinoid tumors could present in different patterns, ranging from nests to sheets, strips, and spindle cells. In the image, the cells have a clear cell pattern, but they share the common features of having uniform nuclei with slightly granular chromatin and inconspicuous nucleoli. Atypical carcinoid tumors usually share the clinical presentation and most of the microscopic features of carcinoid tumors with few exceptions. The tumors are usually larger in size than typical carcinoid tumors, and they have a higher rate for regional lymph node metastasis, ranging between 40% and 50%. There is partial loss of the organoid pattern, and single-cell necrosis or central punctate necrosis is frequent. The mitotic activity is between 2 and 10 per 2 mm2. Nuclear pleomorphism and prominent nucleoli are frequently present. The proliferative index as measured by Ki67 immunolabeling is less than 5% in typical carcinoid tumors and between 5% and 20% for atypical carcinoid tumors. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (LCNEC) usually has a much higher proliferative index than 20% (Figure 7-3). Both types of carcinoid tumors are positive for neuroendocrine markers by immunohistochemistry (IHC). They show positivity for Synaptophysin and CD56, with variable staining for Chromogranin in the case of atypical carcinoid.3 Figure 7-3. Atypical carcinoid tumors demonstrate the cellular features as in a typical carcinoid tumor but with partial loss of architectural organization and the presence of mitotic figures such as seen in the center (arrow) in A. As a surrogate for the mitotic activity, immunolabeling for Ki67 shows brisk activity, as illustrated in B. Small cell lung carcinoma (SCLC) comprises 14% of all lung cancers, and as such it presents 30,000 newly diagnosed cases per year in the United States. About two-thirds of these tumors have a prehilar location and are present around the proximal part of the bronchial tree. They circumferentially involve the endobronchial wall, causing compression of the lumen. However, they rarely involve the mucosal surface to cause ulceration or fungating masses within the lumen. Early lymph node and distant metastasis are common at presentation. The tumor is white-tan and friable with extensive necrosis. In about 5% of the cases, the tumor could present as a coin lesion within the lung parenchyma. Historically, SCLC was classified in three classes: oat cell carcinoma, intermediate cell type, and combined small cell carcinoma with non–small carcinoma.4 In 1988, the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC) recommended dropping the intermediate cell category for lack of reproducibility among pathologists and lack of significant clinical differences. The category of mixed SCLC and non–small carcinoma was maintained, and a mixed small cell carcinoma/large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma category was added. The last category was subsequently included in the 2004 WHO classification for the same reasons cited for the intermediate cell type. Small cell lung carcinoma has very distinctive clinical properties. It has a very aggressive course, and extensive metastasis at the time of presentation is usually expected. SCLC is frequently associated with paraneoplastic syndrome. The mediastinal lymphadenopathy could impinge on the superior vena cava and lead to what is known as superior vena cava syndrome. With combination chemotherapy (etoposide and cisplatin) and radiation chemotherapy to the chest, the median survival for a patient with limited-stage disease is 15 months, and the 5-year survival is 10%. Because of the tendency of SCLC to spread far and fast to other organs, brain radiation and sometimes whole-body radiation are employed in treating this disease, which is very unusual for other lung tumors.5 The role of surgical excision is not standardized, and some surgeons will resect limited-stage tumors to reduce the tumor burden, with surgery followed by systemic chemotherapy.6 Small cell lung carcinoma has very distinctive morphologic features. It is characterized by very hyperchromatic nuclei with an elliptical or fusiform shape demonstrating nuclear molding and very scant cytoplasm. The chromatin is granular or is described as “salt and pepper” with absent or inconspicuous nucleoli. The number of mitotic figures is very high, and apoptotic bodies within the cytoplasm are frequent. There are areas of necrosis and crush artifacts due to the fragility of the cells (Figure 7-4). The same reasons account for the basophilic smearing of adjacent blood vessels by released chromatin, a phenomenon known as the Azzopardi effect. In small forceps-assisted transbronchial biopsies, the crush artifacts could be extensive, so differentiation from peribronchial lymphocytic infiltrate becomes difficult, and resorting to IHC stains becomes inevitable. Figure 7-4. Small cell carcinoma (low magnification view) has a very distinct morphology with hyperchromatic nuclei and a scant amount of cytoplasm. There are areas of necrosis among sheets of tumor cells. Most cases are diagnosed on small biopsies or by cytology. This makes it imperative for pathologists to adhere to the diagnostic criteria as the diagnosis of SCLC is essentially morphologic. There are overlapping features as well as IHC reactivity to neuroendocrine markers. Fortunately, the cytomorphologic features are characteristic, with the high cytoplasmic ratio and nuclear molding the easiest features to note. Apoptotic bodies and stringing of chromatin are also evident. In fact, the diagnosis of SCLC on cytologic material is easier than on small biopsies for the experienced cytopathologist (Figure 7-5). Figure 7-5. Small cell carcinoma, high-magnification view. There is nuclear molding and granular chromatin with absent or faint nucleoli. There are numerous mitotic figures and single-cell apoptosis with areas of necrosis scattered around. Almost 10% of SCLC could be negative for all neuroendocrine markers, and only immunoreactivity to pancytokeratin to exclude hematopoietic and mesenchymal tumors should be relied on to keep the diagnosis as a carcinoma. The positivity of neuroendocrine tumors for pancytokeratin in general, including SCLC, has a characteristic dot-like pattern within the cytoplasm, which could serve as a useful tip-off to the neuroendocrine differentiation in unsuspected cases of poorly differentiated carcinoma. The histomorphologic features are the key to making a diagnosis in these cases. Immunoreactivity to thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1) is another peculiar feature found in 70%-80% of cases of SCLC regardless of the tumor site of origin and should not be interpreted as indicative of derivation from a lung primary.

7

PATHOBIOLOGY OF SMALL CELL CARCINOMA AND OTHER NEUROENDOCRINE TUMORS OF THE LUNG

PREINVASIVE LESIONS

Neuroendocrine Hyperplasia and Tumorlets

Diffuse Idiopathic Neuroendocrine Cell Hyperplasia

Carcinoid Tumorlets

CARCINOID TUMORS

Atypical Carcinoid Tumors

SMALL CELL LUNG CARCINOMA

Clinical Features and Prognosis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree