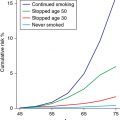

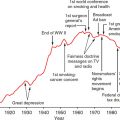

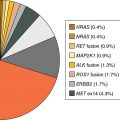

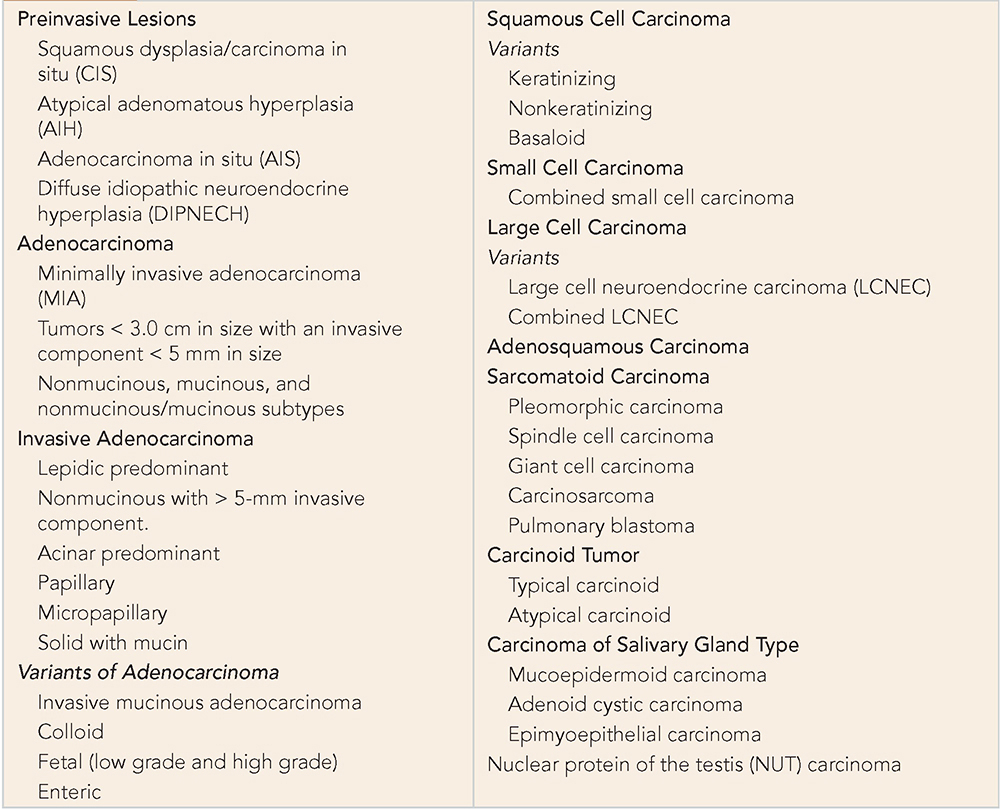

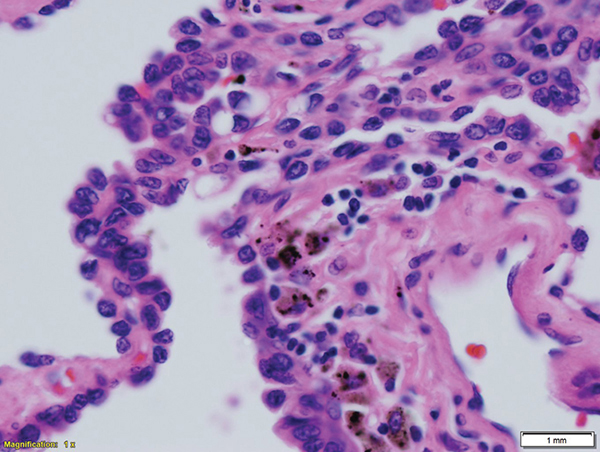

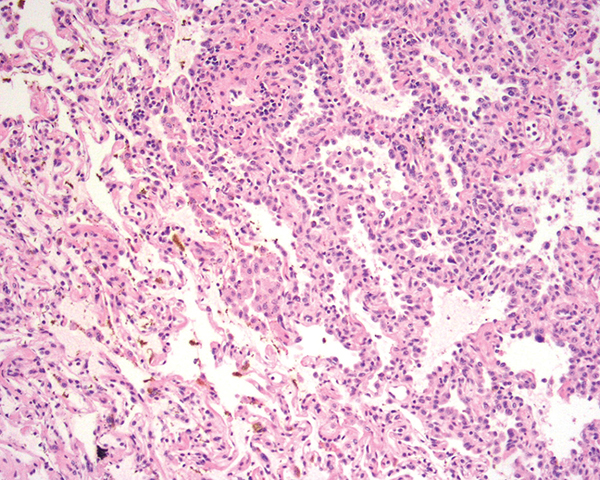

A 60–year-old Asian female had a 4-cm lung mass biopsied by core needle biopsy. She never smoked and has no history of cancer or comorbidities. What testing do you ask for to confirm the suspicion of lung cancer? What other histology findings are important if lung cancer is confirmed? Learning Objectives: 1. What is the new World Health Organization (WHO) classification of lung cancer? 2. What are the markers distinguishing squamous from non-squamous lung cancer? 3. What terminology has replaced the former bronchoalveolar carcinoma? 4. What are scar carcinomas? 5. What are poor prognostic histologies in non-squamous lung cancer? Historically, the basis of all classifications of lung tumors was based on the sections routinely stained with hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) demonstrating the histomorphologic features of tumor cells: cell size and tumor architecture, cellular differentiation along the known types of histology, and the stage at which arrest of differentiation occurs. The biologic behavior was extensively studied, and clinical outcome was correlated with types and even subtypes of tumors based on some peculiar histomorphologic differences. The introduction of ultrastructural, immunohistochemical markers and lately molecular markers has supplemented but not supplanted the morphologic diagnosis. To understand how tumors would behave is to understand how they develop and progress from one stage to another based on a multistep progression model that has been studied over decades. Pathologists have observed this process in other organ systems and concluded it is valid in the case of lung tumors. Lung tumors have been grouped under different major groups with subgroups assigned under those in a branched tree model that not only reserved the broad characteristics but also recognized additional distinctive features. As our understanding of the histogenesis and due to the heterogeneity of tumors, which could create overlapping features and hence confusion, the classification of lung cancer has evolved over the years. The standard classification is the one adopted by WHO, which is meant to be applied worldwide, taking into consideration the variability of practices and differences in the availability of resources in different parts in the world. The last iteration is the one from 2015, and it introduced some transformational improvements based on the revolutionary changes with the advent of targeted therapy and immunotherapy.1 It not only has altered the classification of resection specimens but also has made recommendations applicable for the diagnosis of small biopsies and cytology specimens. Lung cancer can be broadly divided into epithelial tumors and mesenchymal tumors. The former includes 4 major groups: adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, small cell carcinoma, and large cell carcinoma (Table 6-1). Historically, the most important distinction was between small cell carcinoma and non–small cell carcinoma for lack of therapeutic benefit for distinguishing squamous cell carcinoma from adenocarcinoma. A diagnosis of non–small cell carcinoma (not otherwise specified) was frequently used, especially on small biopsies and cytology specimens. Large cell carcinoma served as a wastebasket entity for those tumors with no evident squamous or glandular differentiation. TABLE 6-1 Histologic Classification of Lung Cancer Since the tumors of 70% of patients are unresectable at the time of diagnosis and with the introduction of new targeted therapies that are dependent on the type of histology, it became imperative to further classify the current broad entities into subsets using ancillary studies that reflexes the patients to further molecular testing. Most lung cancer is first diagnosed by small biopsies and cytology, shifting the emphasis to these type of specimens and how to classify tumors based on them.2 In the last iteration of the WHO classification system in 2015, new significant changes were introduced. Chief among them1 are use of immunohistochemistry throughout the classification2; integration of molecular testing for personalized strategies for patients with advanced lung cancer3; a new classification for small biopsies and cytology4; a new classification of lung adenocarcinoma as proposed by the 2011 IASLC/ATS/ERS (International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer/American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society)5; restriction of the diagnosis of large cell carcinoma only to resected tumors that lack any clear morphologic or immunohistochemical differentiation. The pathology of preinvasive lesions has attracted interest from investigators in recent years. As the importance of early detection of cancer has gained popularity, many of these lesions that used to be an incidental finding and characterized as “field defect” are being studied in more detail to understand their impact and provide more understanding in the evolution of cancer. Early classifications of lung cancer did not provide much detail about those lesions except squamous cell carcinoma in situ (CIS). It was not till 1999 that the WHO classification recognized 2 new lesions: atypical adenomatous hyperplasia (AAH) and diffuse idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia (DIPNECH). These designations were maintained as three preinvasive lesions in the subsequent classification in 2004. In the latest 2011 and 2015 editions of the WHO classifications, the entity adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS) was added, which used to be called bronchioloalveolar carcinoma (BAC). The evolution of lung cancer has been understood to follow a multistep progression from a metaplastic, hyperplastic, and finally dysplastic morphology. The bronchial epithelium would undergo squamous metaplasia, which progressively would acquire basal layer hyperplasia, which will eventually turn dysplastic under the influence of carcinogenic stimulation like that encountered in the cases of smoking.3 In the same fashion, multiple molecular “hits” have been reported to occur along this course. Such changes include the allelic loss of the 3p region, which represents an early event in 78% of preinvasive bronchial lesions.4 Other events are known to follow that, including loss of heterozygosity at 9p21 corresponding to (p16), 17p loss in cases of hyperplasia; telomerase activation and retinoic acid receptor (RAR) B in cases of mild dysplasia; p53 mutation in moderate dysplasia; and bcl-2 and cyclin D and E overexpression in cases of CIS.5 Squamous atypia could occur in the setting of severe inflammation and in the cavitary lesion of aspergillosis and should not be overcalled as dysplasia/CIS. Grading of squamous cell dysplasia has been attempted. Some authors advocated a three-tier system with mild, moderate, and severe dysplasia based on how far the dysplastic features extended within the full thickness of the metaplastic squamous mucosa and dividing the thickness into thirds, with each grade assigned to each third of involvement. The difference between severe dysplasia and CIS was based on the presence of any maturing or flattened layer of squamous cells near the top of the metaplastic layer. If full thickness was involved, a diagnosis of CIS was rendered. Other authors advocated a two-tier system for dysplasia, eliminating the middle category. However, this system did not provide any clinical utility, and it was difficult to achieve reproducible results as these lesions tend to change their severity from one focus to another, and there is much overlap in features to produce consistent results. Caution must be exercised in areas of prior biopsies and ulceration or squamous metaplasia of the seromucinous glands around the bronchial wall to avoid overcalling these foci as invasive squamous cell carcinoma. Atypical adenomatous hyperplasia (AAH) is a bronchioloalveolar proliferation that resembles, but does not fulfill the criteria, for AIS with a size less than 5 mm. It is usually encountered as an incidental finding in lung resection specimens. The incidence ranges between 5.7% and 21.4% depending on the extent of the search and criteria applied to the diagnosis. It is important to recognize it as a separate lesion and not an intrapulmonary metastatic lesion. It is characterized by a proliferation of atypical cuboidal cells replacing the original alveolar cells, with an abrupt transition from type I pneumocytes to atypical cells, as opposed to the gradual transition that occurs in reactive changes in the alveolar lining in cases of infection and inflammation (Figure 6-1). There could be several lesions within the lung, suggesting that this type of lesion represents a “field defect” rather than spread through air spaces (STAS).6 Several molecular mutations like those encountered in AIS have been detected in these lesions, making them preinvasive lesions.7 Earlier attempts at grading these proved difficult due to lack of interobserver reproducibility and lack of clinical or therapeutic benefits. There are no data to infer any negative prognostication on patients with AAH when compared with those without.8 Figure 6-1. Atypical adenomatous hyperplasia shows atypical bronchioloalveolar cell proliferation with large dark nuclei lining alveolar spaces. They are small in size (<5.0 mm). In the current adenocarcinoma classification, AIS is defined as a glandular proliferation measuring less than 3 cm that has a pure lipidic pattern with no invasion (Figure 6-2). In most cases, the cells are of the nonmucinous type; rarely, they could represent a mucinous type. These were formerly known as BAC. When they are completely resected, the overall prognosis is 100%. On computed tomographic (CT) scan, they appear as ground glass attenuation if they are of the nonmucinous and as a solid nodule if they are of the mucinous type. In the past classification, the term BAC used to cover the nonmucinous type as well as the mucinous type of BAC. It has been recognized that these are two different types of tumors with different biology and different clinical outcomes. Figure 6-2. Adenocarcinoma in-situ, nonmucinous type. Classically, tumor cells are shown that abruptly stop at the interface with benign lung parenchyma, in contrast to the gradual blending that occurs in reactive lung changes where type II pneumocytes would merge with type I pneumocytes. Nonmucinous AIS tends to harbor EGFR mutations and could occur in non-smokers and never smokers. Mucinous AIS proved to be very rare in its purist form and usually expresses a K-ras mutation similar to those encountered in patients with a history of cigarette smoking. Even rarer is the occurrence of the combination of nonmucinous and mucinous AIS. For a diagnosis to be made, there should be no evidence of invasion, as would be manifested by the presence of thickened stroma, with chronic inflammation as an indication of host response to an invasive carcinoma. In their mucinous form, they show on CT imaging as a pneumonia-like presentation, whereas the nonmucinous type has the morphology of ground glass attenuation.9 Adenocarcinoma accounts for 38% of all lung cancers in the United States. The subclassification of adenocarcinoma of the lung has undergone some transformational change in the last two decades. It started with a somewhat obscure historic controversy surrounding so-called scar carcinoma. One camp of investigators believed that this type of adenocarcinoma usually arises from a preexisting scar from the proliferation of cells within the scar or the surrounding environment. Other authors believed that this was an active fibrotic process representing the host response to the invading carcinoma. Studying those scars diligently led to the recognition that the presence of a scar has an adverse prognostic outcome and, going even further, proved that the size of the scar correlated with the prognosis.10 Based on this observation and others, the current classification no longer recognizes BAC diagnostic terminology. The concept of minimally invasive adenocarcinoma (MIA) was introduced, and the mixed subtype was eliminated and replaced by a predominant type and reference to the percentage of tumor subtypes within a heterogeneous adenocarcinoma. Certain subtypes of adenocarcinoma proved to have worse prognosis than others. For instance, micropapillary and solid adenocarcinoma with mucin have a worse prognosis than the acinar and papillary types of adenocarcinoma.11 The lipidic pattern is considered as a low-grade type of adenocarcinoma and carries a much better prognosis. It is also the subtype that more likely to harbor EGFR mutations and hence respond to the tyrosine kinase inhibitors set of drugs. Minimally invasive adenocarcinoma is defined as a lipidic-predominant tumor measuring 3 cm or less in maximum dimension, with 5 mm or less of an invasive component. Multiple studies support the notion that the patients with MIA have a near 100% 5-year disease-free survival (DFS). Most of these cases are of the nonmucinous type, but rarely mucinous cases could occur. The presence of a scar is the major criterion separating AIS from MIA. It is very important to carefully sample these tumors to adequately measure the largest dimension at the right plane of sectioning. CT measurement of the solid portion in an otherwise ground glass lesion could be used as a surrogate for the estimation of the invasive portion if the measurement of the lesion proved to be difficult to measure during the gross examination or on the slides.9 An adenocarcinoma with an invasive component in excess of 5 mm is considered an invasive adenocarcinoma. It should be further subclassified based on the predominance of one component, or if there is more than one component, a percentage of each should be presented in increments of 5%-10%. Since certain subtypes are known to have a worse prognosis, they should be mentioned in the pathology report. Signet ring and clear cell subtypes are now considered cytologic features and do not represent histologic subtypes. Of note, carcinoma with a signet ring feature is the most frequent subtype to express mutations in the ALK gene. The recognized subtypes of adenocarcinoma are listed in Table 6-1. The most recognized pattern is the lipidic pattern, which is basically the AIS component accompanying an invasive component. This is called lipidic-predominant adenocarcinoma (LPA). This used to be called a mixed subtype of adenocarcinoma with a mixture of BAC and acinar types of adenocarcinoma. By CT imaging, the lipidic pattern is represented by ground glass attenuation, and the invasive component shows as a speculated mass within that area.

6

PATHOBIOLOGY OF NON–SMALL CELL LUNG CARCINOMA

CLASSIFICATION OF LUNG TUMORS

PREINVASIVE LESIONS

Squamous Cell Dysplasia and Carcinoma in Situ

Atypical Adenomatous Hyperplasia and Adenocarcinoma in Situ

Adenocarcinoma in Situ

ADENOCARCINOMA

Adenocarcinoma Diagnosis in Resected Specimens

Invasive Adenocarcinoma

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree