Introduction

The Need for Clinical Trials Involving Older People

The ageing of the global population has brought about a greater need to understand the health status, underlying risk factors and prevention and care needs of older people.1 Observational epidemiological studies on ageing, such as the Baltimore Longitudinal Study on Aging, Women’s Health and Aging Study, Health Aging and Body Composition Study, Rotterdam Study and PAQUID, are now well established and have shown that the recruitment and retention of older adults in clinical studies are clearly feasible.

The most reliable evidence regarding the efficacy of interventions aimed at preventing, curing or managing a disease or health status comes from randomized controlled trials. However, traditionally, older people have been excluded from such studies,2 meaning that the level of participation in clinical trials is highly disproportionate to the level of health burden, healthcare expenditure and prescription drug use in this population.3 For example, in cancer trials, only around one-third of participants are thought to be elderly, whereas over 60% of incident cancers occur in elderly persons.4, 5 Older adults are even under-represented in trials for diseases that almost exclusively affect older people, such as osteoarthritis6 and dementia.7 Aside from the evident need to test treatments for specific age-related diseases, such as dementia, age-related macular degeneration, osteoporosis or cataracts, in elderly populations, another important reason for conducting clinical trials on older people is that in this population drug doses may need to be adapted to physiological changes associated with old age in order to avoid serious adverse events, and also the high level of comorbidities and concomitant medications must be taken into account.

Why are Older People Excluded from Clinical Trials?

There are various potential reasons for the exclusion of elderly people from clinical trials, for example, patient fear and misunderstanding of research, physician bias against suggesting enrolment in trials (perhaps through fear that elderly people will not be able to withstand aggressive therapies) or too rigorous exclusion criteria that eliminate many potential participants.8, 9 Although age in itself is not now generally used as an exclusion criterion, older people may be excluded from trials on the basis of haematological, hepatic, renal or cardiac abnormalities that may be widespread in this population. Furthermore, trial participants may be required to be ambulatory, to be able to walk and to be able to carry out activities of daily living independently, thus excluding further categories of older people. The use of strict inclusion and exclusion criteria for clinical trials is favoured by researchers since it ensures a more homogeneous study population, which may facilitate demonstration of efficacy. However, trials based on such populations provide little indication of real-life effectiveness.

Even if the inclusion and exclusion criteria allow their participation, investigators may be deterred from enrolling older subjects due the numerous methodological difficulties of conducting research with older people, for example, high rates of dropout or death, selection bias and the presence of comorbidities and multiple medicines (polypharmacy). Rates of attrition (or ‘dropout’) are higher in trials carried out in older populations than those carried out in younger individuals,10 which reduces the statistical power of trials to detect treatment effects and can affect the validity of the results obtained. High attrition rates can be brought about in trials of older adults due to death, worsening health, decreasing autonomy, institutionalization and refusal to continue trial participation, often because of the perceived burden of study visits. Also, trials for older people often require the participation of another family member or close friend, at the very least in order to transport or accompany the participant to study visits, but in some cases to act as a proxy in order to give information about the patient’s health status and/or quality of life if the patient is incapable of giving this information him- or herself. This may impact on attrition bias, since if the family member cannot or does not want to participate, then the participant will have to withdraw from the study. There may also be problems with the validity of using information gained from proxies since one cannot be sure that it is a valid or reliable measure of the patient’s actual health status. A further problem in trials of older people is selection bias, since older individuals who participate in research studies are generally healthier than those in the general population. Finally, elderly people are likely to have a high rate of comorbidities and risk factors for various diseases, which bring about risks of drug interactions, side effects, death and hospital admission, all of which may be seen as having negative influences on trial findings.

Consequences of the Exclusion of Older Adults from Clinical Trials

The exclusion of older people from clinical trials limits the generalizability of their findings, since there will be insufficient data about positive or negative effects of treatment in this specific population, which may well contain individuals with the greatest need for new treatments.5 This can result in suboptimal treatment for older people—either through not receiving potentially useful therapies because of a lack of evidence or through exposure to unnecessary risks because of a lack of information on adverse events in older people of therapies tested in trials involving primarily younger subjects.11

There are therefore now calls for trial participants to be more representative of the patient population for the disease under study;12 for many chronic diseases, this will require the inclusion of significantly more older people. Despite the methodological complexities highlighted above, it has been demonstrated that clinical trials can be successfully carried out both in healthy older subjects13 and also in those with serious illnesses.14 Furthermore, it has been shown that older people are willing to participate in clinical trials.11

Given the projected increases in the number of older adults in the coming years, there is an urgent need to develop new interventions for the prevention, treatment or management of age-related syndromes and diseases. It is therefore important to increase the participation of older adults in clinical trials.

Summary of Existing Clinical Trials Involving Older People

Clinical Trials Reported in the Literature

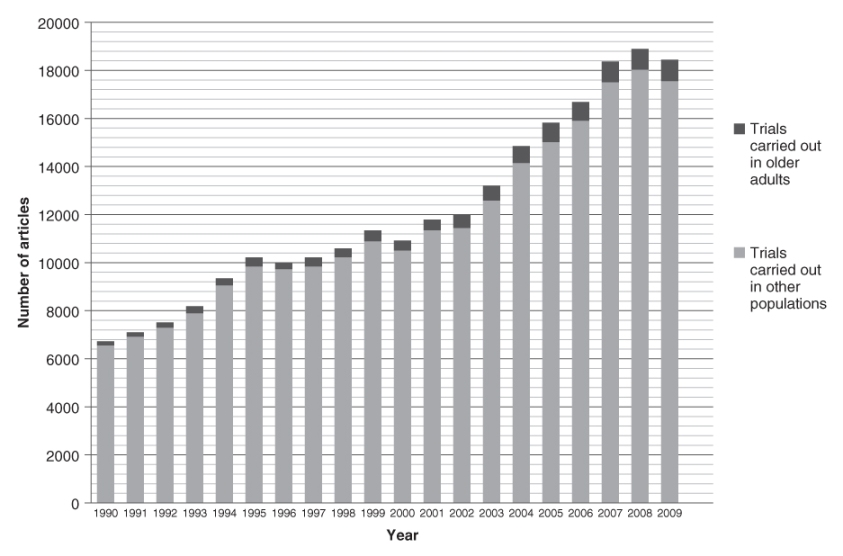

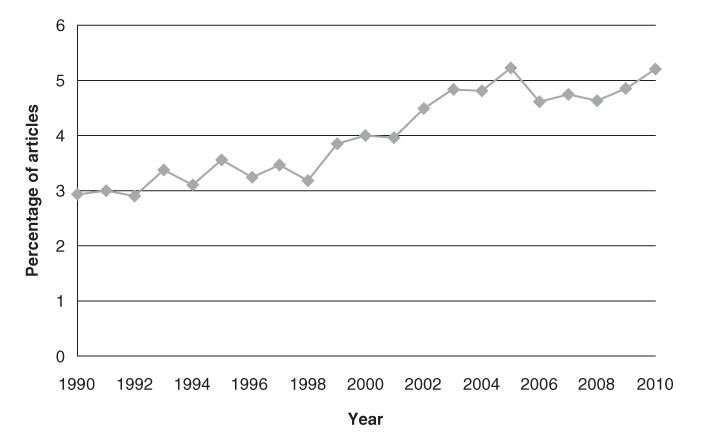

A search was carried out in the PubMed database in order to quantify the number of clinical trials for older people reported in the literature since 1990. The total number of articles per year indexed in the database and classed as randomized controlled trials has tripled in the last two decades, gradually increasing each year from ∼6700 papers in 1990 to ∼18 000 papers per year in 2007–2009 (Figure 132.1). The proportion of these trials conducted specifically in older populations has also increased over time from ∼3% per year in the 1990s to ∼5% per year since 2003 (Figure 132.2).

Figure 132.1 Number of articles indexed in PubMed reporting randomized controlled trials, by year of publication.

Figure 132.2 Percentage of articles indexed in PubMed reporting randomized controlled trials carried out specifically in older subjects, by year of publication. Results for 2010 do not include the whole year (search carried out in August 2010).

Clinical Trials Recorded in an Online Registry

Another source of information about clinical trials is the online clinical trials registry ClinicalTrials.gov. A search in August 2010 showed that there were 266 intervention trials specifically for ‘seniors’ registered in the database. These studies represented 0.4% of the total number of registered intervention trials.

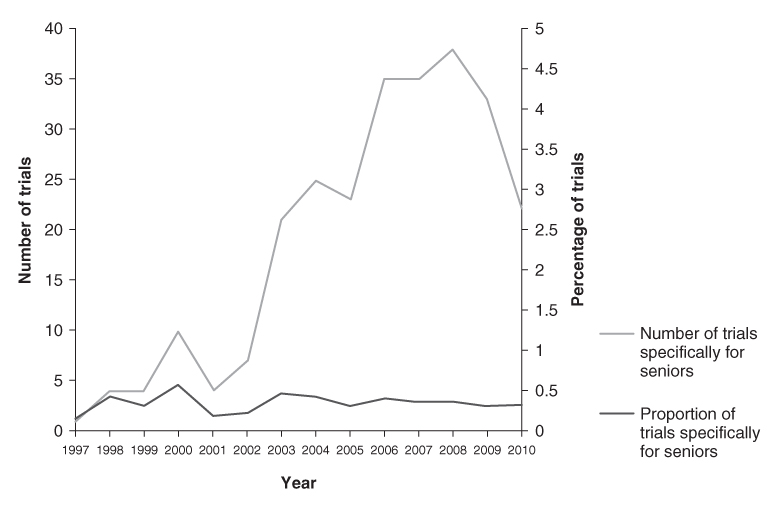

The earliest registered trial that was specifically for seniors began in 1990, but there were only two such trials prior to 1997. Between 1998 and 2002, there were between 4 and 10 trials per year for seniors and since 2003 there have been more than 20 trials per year (Figure 132.3). Since 1997, these trials have generally represented less than 0.5% of all intervention trials per year (Figure 132.3).

Figure 132.3 Number (grey line) and percentage (black line) of intervention trials specifically for seniors registered in the ClinicalTrials.gov database, by trial start year. Results for 2010 do not include the whole year (search carried out in August 2010).

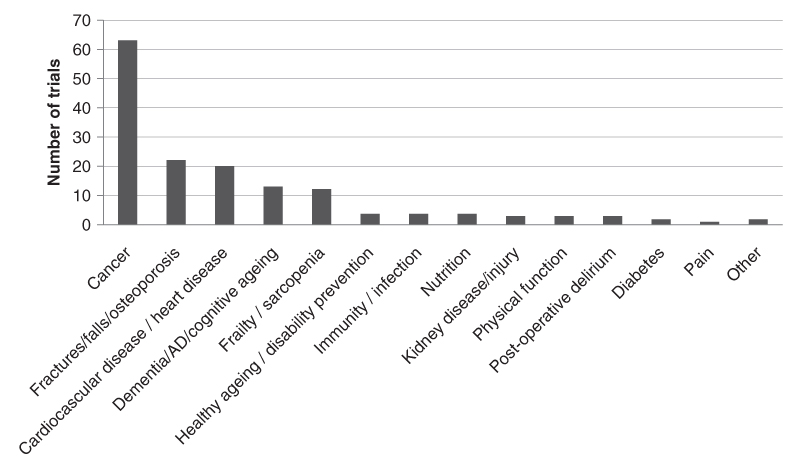

Of the 266 seniors trials identified, 156 were ongoing or not yet started as of August 2010 (recruitment status: ‘Recruiting’; ‘Enrolling by invitation’; ‘Active, not recruiting’; or ‘Not yet recruiting’). Most of these trials were focused on a specific condition such as cancer (N = 63) or cardiovascular disease (N = 20), whereas others were targeted towards more general syndromes of ageing, such as frailty and sarcopenia (N = 12) or ‘healthy ageing’ or the prevention of disability (N = 4) (Figure 132.4).

Figure 132.4 Primary conditions targeted by the 156 ongoing clinical trials specifically for seniors registered in the ClinicalTrials.gov database.

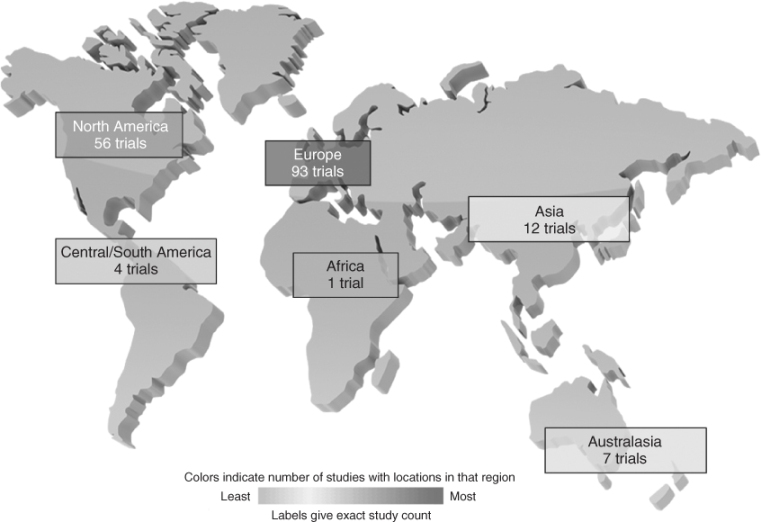

Most of these trials for seniors are taking place in Europe (N = 93) and North America (N = 56), with other regions clearly under-represented, participating in at most 12 trials (Figure 132.5). Africa is the least represented region in clinical trials for seniors and is only participating in one trial at the present time.

Figure 132.5 Participation by region in ongoing clinical trials specifically for seniors registered in the ClinicalTrials.gov database.

Determinants of Participation of Older People in Clinical Trials

The factors that motivate older adults to participate in clinical trials may differ from those that motivate younger individuals. The specific identification of barriers and motivators that prevent or facilitate the enrolment of older adults in clinical trials, and also factors that are predictive of enrolment, can inform the development of strategies aimed at increasing the participation of this population of individuals in future trials.

Patient Factors

Patient Factors Associated with Participation or Non-Participation

There are few studies that have made a detailed comparison of the characteristics of older people who enrol in clinical trials with those who do not enrol, perhaps due to the ethical difficulties of obtaining detailed information from non-participants. Other studies have assessed factors associated with willingness to participate in a clinical trial, often in a hypothetical situation, rather than actually comparing those who do and do not participate in an actual trial.

Sociodemographic Factors

Whereas some studies have found no difference in terms of demographic characteristics between older adults participating in certain trials and those not participating,15, 16 others have suggested that age and level of education or socioeconomic status can affect older adults’ participation in clinical trials. A review of the literature noted that older people with a lower level of education or lower socioeconomic status are less likely to want to participate in research or actually do so.11 Indeed, non-participants in a lifestyle intervention trial for patients with stable cardiovascular disease had a lower level of education than participants,17 as did non-participants in an intervention study on successful ageing for people aged 65 years compared with participants in this study.18

Even for clinical trials specifically targeting older adults, age seems to be predictive of trial participation. For example, in a primary prevention trial for Alzheimer’s disease for people aged 75 years or older, persons under age 85 years were more likely to enrol than those aged over 85 years.19 Also, participants in an intervention study on successful ageing for people aged 65 years or more were younger than non-participants18 and non-participants in a lifestyle intervention trial for patients with stable cardiovascular disease were older than participants.17

There is little information regarding gender differences between participants and non-participants in clinical trials for older adults, although it was noted that men were more likely to enrol than women in a primary prevention trial for Alzheimer’s disease.19

Disease Severity and General Health Status

There is little information regarding the relationship between disease severity and trial participation in older adults.

General health status may affect older adults’ participation in clinical trial since it was found that participants in an intervention study on successful ageing had better physical status and functional abilities and fewer depressive symptoms than non-participants.18 Another study showed that while eligible refusers and participants (from the usual care control group only) in a disability prevention trial in older adults were similar in terms of self-perceived health at baseline, refusers had a significantly higher rate of mortality [adjusted relative risk (RR) 1.49; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.15–1.93; p = 0.002] during 3 years of follow-up.16

Other Factors

Other factors that may be associated with trial participation amongst older adults include prior experience or knowledge of clinical trials,11 the person giving the informed consent for participation (the patient him/herself or a proxy if the patient is incapable of giving their own consent) and marital and working status. For example, patients themselves were more likely to accept to participate in an acute stroke trial than proxies (if the patient was incapable of giving informed consent)15 and non-participants in a lifestyle intervention trial for patients with stable cardiovascular disease were more likely to be single and less likely to be working, compared with participants.17

Patient-Related Motivators for Participation

As a complement to the identification of patient characteristics associated with participation in clinical trials, some studies have attempted to determine the reasons driving older adults’ participation in clinical trials.

Personal Benefit

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree