It has been well documented that a paravertebral block (PVB) reduces the stress response in patients with breast cancer, and PVB has been used in various surgical procedures and for the management of chronic pain.1 PVB is a form of regional anesthesia and was first performed by Hugo Sellheim of Leipzig, Germany in 1905 as a replacement for spinal anesthesia.2 The literature describes PVB being used in the thoracic and lumbar regions in a unilateral and bilateral fashion. PVB may be used for multiple surgical procedures, including, but not limited to, thoracotomy, laparoscopic or open cholecystectomy, colectomy, gastrectomy, abdominal and inguinal hernia repairs, appendectomy, transurethral prostatectomy, hip replacement, and total knee replacement.3 At The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, we primarily use PVB for breast cancer–related surgeries, including mastectomies, axillary dissections, and breast reconstruction.

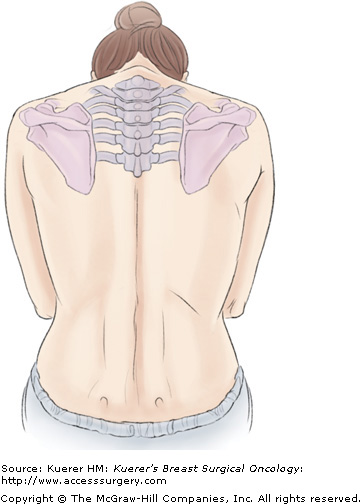

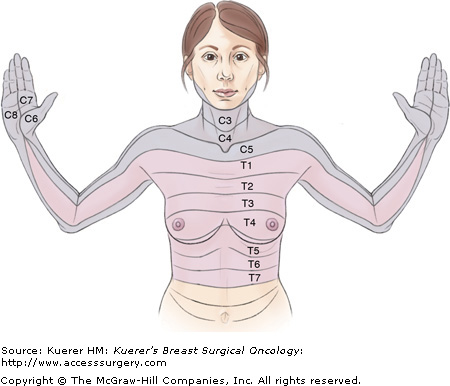

The thoracic paravertebral space is the space on each side of the vertebrae. For breast surgery, we use the T1 through T6 paravertebral spaces. Anterolaterally, the space is formed by parietal pleura; medially, the space is formed by the vertebral body, intervertebral disk, and intervertebral foramen; and posteriorly, the space is formed by the superior costotransverse ligament. The intercostal space is lateral to the paravertebral space and contains the intercostal nerve, and the epidural space is medial to it. In the paravertebral space, the spinal nerves are not covered by the fascial sheath.4

PVB is used for unilateral and bilateral breast surgery, as well as postmastectomy breast reconstruction. To be candidates for undergoing PVB, patients have to meet certain minimum requirements. First, the surgical field should not exceed the area being covered by the block. Second, the anesthesiologist, the surgeon, and the patient should agree on the necessity of the block. The patient’s anatomy should be compatible with the block, as discussed below. We also routinely perform PVB in patients who are undergoing bilateral mastectomies with breast tissue expander placements (Figs. 52-1 and 52-2).

In an attempt to be time efficient, placement of the PVB is performed in the preoperative holding area.4 During the actual placement of the paravertebral block, the patient is fully monitored (oxygen saturation as measured by pulse oximetry, electrocardiogram, noninvasive blood pressure with supplemental oxygen) with resuscitation and intubation equipment immediately available if necessary.4 At MD Anderson Cancer Center, we routinely block the Thoracic 1 (T1) through Thoracic 6 (T6) paravertebral spaces for many of our breast surgical procedures (eg, modified radical mastectomy, total mastectomy, axillary dissections, cosmetic breast surgical procedure such as tissue expanders, breast augmentation with implants, and mastopexy). Most of the patients who undergo PVB also receive a general anesthetic during surgery. The PVB is primarily used for postoperative pain control.

Patients who undergo PVB are placed in the sitting position and sedated with midazolam 2 mg administered intravenously (IV), fentanyl 50 to 100 μg IV, and a titrated dose of propofol.5 All patients receive promethazine 6 mg IV and famotidine 20 mg IV before actual placement of the PVB. The literature suggests that placement of the PVB can occur in the lateral decubitus position and the side being blocked in the elevated aspect of the patient.6

PVB is generally performed with the patient in the sitting position; the patient’s neck should be flexed, shoulders dropped forward, and back arched, and the patients’ chin should rest on the chest, with the patient slightly leaning forward.4 The needle entry point is found by observing the midline of the superior aspect of the thoracic spinous processes (T1-T6), measuring 2.5 cm unilateral or bilaterally, and marking the point of entry, which should overlie the inferior aspect of the transverse process.7 The patient’s back is cleaned and prepped in the usual sterile fashion with povidone-iodine or chlorhexidine gluconate and then anesthetized with a local anesthetic at the needle entry site in a unilateral or bilateral manner. Ropivacaine 1% (2-3 mL) is injected subcutaneously along the line where the injections should be made.8 The amount of sedation required to place the PVB is one that requires the patient to be cooperative and the airway maintained without assistance.5

The transverse process should be expected to be contacted 2 to 4 cm beyond the point at which the needle penetrates the skin.5 Knowledge of the approximate depth from the skin to the paravertebral space is required for safe and effective placement of the PVB.6 The approximate median depth of the skin to the paravertebral space is 55 mm in the T1 to T6 dermatome levels.6 It has been well documented that a patient’s body mass index (BMI) influences the distance between the skin and paravertebral space.6 Thus the greater the BMI, the greater the distance from the skin to the paravertebral space.

Using a 22-gauge 10-cm Tuohy spinal needle attached with extension tubing to the syringe containing the local anesthetic, the needle is incrementally advanced approximately 1 mm anteriorly and is perpendicular to the back in all planes until the transverse process is contacted.5 The needle is then withdrawn from the transverse process and walked off in a caudal fashion.5 Once all contact from the transverse process is lost, the needle is then advanced approximately 1 cm to the paravertebral space.5,9 If the needle is inserted at the appropriate depth and the transverse process is not contacted, then the needle is probably between 2 transverse processes.4 Advancing the needle to a deeper depth is not recommended; instead, the needle should be withdrawn and redirected in a cephalad or caudal fashion until the transverse process is located.4 If the angle is too extreme while attempting to walk off the transverse process in a caudal fashion, the needle is probably contacting the transverse process in the superior aspect instead of the desired inferior aspect.4 In this situation, there are 2 recommended options. One option is to withdraw the needle back to the skin and reinsert the needle approximately 0.5 to 1.0 cm inferiorly to locate the paravertebral space.4 Another option is to walk off the transverse process in a cephalad fashion, remaining cognizant of the fact that the nerve root is being blocked 1 level higher than originally intended.4 If the 22-gauge Tuohy needle advances beyond the appropriate depth, it may contact bone, which is probably the rib, because the ribs are anterior to the transverse process. Once again, the needle should be withdrawn to find the desired superficial contact of bone, and this should be the transverse process.4

When the Tuohy needle passes through the costotransverse ligament, it causes a “popping” sound, and a loss of resistance is felt. However, relying on the popping sound is not always pathognomonic for locating the paravertebral space when one has successfully walked off the transverse process.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree