Pancreatic Surgery

CRITICAL ELEMENTS

Evaluation for Extrapancreatic Disease and Assessment of Locoregional Tumor Anatomy

Pathologic Examination of the Surgical Specimen

1. EVALUATION FOR EXTRAPANCREATIC DISEASE AND ASSESSMENT OF LOCOREGIONAL TUMOR ANATOMY

Recommendation: Staging laparoscopy should be performed prior to laparotomy to exclude radiographically occult metastatic disease. If no such disease is identified, a thorough, open exploration to identify local infiltration or metastases not revealed during laparoscopy should be conducted before tumor resection.

Type of Data: Primarily retrospective, low-level evidence.

Strength of Recommendation: Strong.

Rationale

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma has a high malignant potential, and the majority of patients have metastases at diagnosis. Pancreatectomy is not associated with a survival benefit in these patients.1,2 Pancreatic cancers may also infiltrate locally into the retroperitoneum and root of the mesentery to involve the superior mesenteric artery (SMA), aorta, and/or celiac trunk, and such involvement precludes a safe and effective margin-negative resection. Unfortunately, even the most advanced cross-sectional imaging and echoendoscopy tests do not have the capacity to detect all low-volume metastatic disease. Therefore, for patients with ostensibly localized pancreatic cancer, rigorous operative staging is critical.

Staging Laparoscopy

The evolution of multidetector row computed tomography and advanced magnetic resonance imaging has increased the accuracy with which the anatomic extent of the primary cancer can be determined. However, the capacity of these modalities to identify small (<1 cm) metastases to the liver or peritoneum remains limited.3 Therefore, a thorough examination of all visceral and parietal surfaces before tumor resection is mandatory. Historically, this examination was accomplished via laparotomy, and patients found to have radiographically occult metastases or unresectable locoregional disease would undergo surgical biliary and enteric bypass to palliative or prevent symptoms of biliary or gastric outlet obstruction.

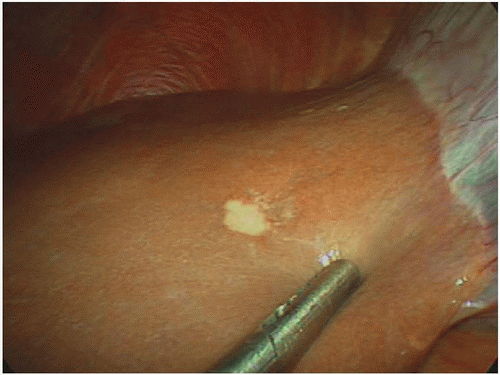

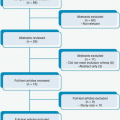

Steady advances in endoscopic and laparoscopic techniques have substantially reduced the need for open palliative operations, thereby limiting the role of exploratory surgery to staging alone. Staging laparoscopy was first used as a minimally invasive technique to identify occult metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) lesions in 1978, obviating the need for nontherapeutic staging laparotomy and its associated morbidity, costs, and delay of definitive oncologic therapy (Fig. 13-1).4 When the procedure was first introduced, some voiced concerns about its possible association with trocar site disease and peritoneal dissemination, but subsequent studies did not support these concerns, so the use of staging laparoscopy became more widespread.5 Many now advocate laparoscopic staging for all patients with potentially resectable pancreatic cancer prior to open exploration and resection.6,7,8,9 When utilized liberally, staging laparoscopy radiographically may identify occult metastases in 14% to 37% of patients.

Selective Laparoscopy

Staging laparoscopy is most cost-effective when its findings redirect patients with unresectable disease from unnecessary open operative exploration to nonsurgical palliation. Staging laparoscopy becomes increasingly less cost-effective when yield decreases as preoperative imaging improves or as tumor biology becomes increasingly favorable and the risk of metastatic disease decreases. Thus, staging laparoscopy is most costeffective when it is utilized selectively in patients whose primary cancers are located in the pancreatic body or tail, are large or anatomically extensive, are associated with a high cancer antigen 19-9 level, are associated with equivocal computed tomography findings of metastasis, and/or are associated with clinical findings suggesting advanced disease, such as marked weight loss.10,11,12,13,14,15,16 In these scenarios, the use of staging laparoscopy is particularly encouraged.17,18

Advanced/Extended Staging Laparoscopy

Although laparoscopy facilitates the detection of small, superficial metastases on the liver and in the peritoneum that are easily missed using radiologic staging techniques, a simple laparoscopic survey of the abdomen may not detect locally advanced disease and vessel encasement that would also represent a contraindication to resection.19 Modifications to improve the accuracy of laparoscopic staging have included the use of extensive wider laparoscopic dissections and laparoscopic ultrasonography to more thoroughly inspect vascular structures and evaluate occult intrahepatic lesions, extraanatomic lymph node involvement, and extrapancreatic tumor extension.8,9 Although retrospective analyses have shown that all these techniques have added benefits, their detection yield has diminished as significant improvements in preoperative imaging have been made.15,16 In general, advanced laparoscopy appears to have limited capacity to detect unresectable locoregional tumor extension in patients who have no radiographic evidence of locally advanced disease.

Peritoneal Lavage

Because pancreatic tumors shed malignant cells into the peritoneum, laparoscopic lavage has been proposed as an additional index of resectability. Several early studies showed that patients with positive peritoneal washings developed metastasis earlier and had shorter survival durations after resection than did patients with negative peritoneal washings.20,21,22 The results of subsequent investigations have suggested that positive peritoneal cytology alone (without other visible evidence of metastatic disease) should not necessarily preclude resection in pancreatic cancer patients whose tumors would otherwise be considered resectable, as these patients may still achieve long-term survival.23,24 Regardless, until additional high-level evidence is found to support its widespread use, routine use of peritoneal lavage cannot be recommended at present. It may be used selectively for patients at high risk for surgery to provide support for a nonoperative therapeutic approach.

Timing of Laparoscopy

Staging laparoscopy should typically be performed at the time of the planned resection. Staged procedures to allow time for biopsy specimen analysis, particularly those

utilizing peritoneal cytology results as a determinant for proceeding to resection, have been described; however, because these procedures carry additional costs and require additional resources, their routine use in the absence of other obvious indications is not recommended.

utilizing peritoneal cytology results as a determinant for proceeding to resection, have been described; however, because these procedures carry additional costs and require additional resources, their routine use in the absence of other obvious indications is not recommended.

Technical Aspects

Technique of Staging Laparoscopic Exploration

Camera port incisions can be made along the proposed lines of the laparotomy incision or (most commonly) periumbilically. Following carbon dioxide insufflation, an angled (≥30°) laparoscope is used to visually inspect the abdominal cavity, including the peritoneal, diaphragmatic, and hepatic surfaces and the porta hepatis, for evidence of occult metastases. Additional trocars may be placed to elevate the liver lobes and mobilize viscera to facilitate a more thorough evaluation of the pelvis for drop deposits specifically and the mesenteric root for evidence of tumor extension or matted nodes. Abnormal lesions, which may vary in size and morphology but typically appear firm and have evidence of microvasculature, should be biopsied, and the samples should be sent for frozen section pathologic evaluation.

Beyond simple laparoscopic maneuvers for visual evaluation of the peritoneal and visceral surfaces, additional extensive laparoscopic maneuvers are not considered standard. Such maneuvers include elevating the omentum from the transverse colon to access the omental bursa, performing a partial kocherization and evaluating the aortocaval nodes, and dividing the gastrohepatic ligament and examining the caudate lobe surface and celiac axis. At some centers, laparoscopic exploration is performed in conjunction with laparoscopic ultrasonography. These types of advanced laparoscopic evaluations of the extent of locoregional disease may be best reserved for patients undergoing planned minimally invasive resections, in which laparoscopic palliative procedures can be performed without formally converting to laparotomy.

Technique of Open Exploration for Staging

Formal laparotomy is reserved primarily for potentially curative operations. If no evidence of obvious unresectability is identified at laparoscopy, conversion to open exploration is performed. The incision used for open exploration depends on surgeon preference and abdominal anatomical considerations and is typically a midline, or bilateral, subcostal incision. The surgical field is then thoroughly examined to identify any other occult disease not easily visualized by laparoscopy and to assess extrapancreatic extension and locoregional resectability. The omental bursa is accessed by dividing the gastrocolic ligament and elevating the omentum from the mesocolon. For lesions in the pancreatic body or tail, the dissection is extended sufficiently to the left to facilitate full visualization of the pancreas to its tail and the hilum of the spleen. For proximal lesions, the hepatic flexure is mobilized inferiorly by dissecting in the avascular plane between the hepatic flexure and the duodenum and performing an extended Kocher maneuver to free the third portion of the duodenum from the colonic mesentery. The gastrocolic venous trunk or middle colic vein is used as landmark to identify the superior mesenteric vein (SMV) inferior to the neck of the pancreas, where the SMV is assessed for direct tumor involvement. Tumor involvement of the

SMA is classically assessed by placing one’s hand posterior to the pancreatic head after kocherization; however, SMA involvement should be readily apparent if highquality preoperative imaging studies have been performed and skillfully interpreted, and any discrepancy between imaging and intraoperative findings should be met with caution. The porta hepatis is assessed for direct tumor infiltration, and the root of the mesentery should be evaluated to rule out nodal disease outside the surgical field. Once locoregional extent has been thoroughly evaluated, formal dissection to resect the tumor and involved tissues begins.

SMA is classically assessed by placing one’s hand posterior to the pancreatic head after kocherization; however, SMA involvement should be readily apparent if highquality preoperative imaging studies have been performed and skillfully interpreted, and any discrepancy between imaging and intraoperative findings should be met with caution. The porta hepatis is assessed for direct tumor infiltration, and the root of the mesentery should be evaluated to rule out nodal disease outside the surgical field. Once locoregional extent has been thoroughly evaluated, formal dissection to resect the tumor and involved tissues begins.

Conclusion

Despite improvements in modern radiographic imaging studies and the use of these studies’ findings to predict locoregional unresectability, cross-sectional imaging studies and echoendoscopy remain relatively nonspecific tests for predicting resectability owing to radiographically occult peritoneal metastases and/or liver metastases in a significant proportion of patients with seemingly localized pancreatic cancer. Minimally invasive procedures and thorough intraoperative evaluation continue to have important roles in staging pancreatic cancers prior to resection with curative intent.

2. PATHOLOGIC EXAMINATION OF THE SURGICAL SPECIMEN

Recommendation: Communication between surgeons and pathologists is essential for the accurate reporting of margin status following pancreatectomy. A standard nomenclature should be used to describe surgical margins. For pancreatoduodenectomy specimens, the status of the pancreatic neck margin, bile duct margin, anterior surface, posterior surface, portal vein/SMV groove, and SMA/uncinate margin should be described. For distal pancreatectomy specimens, the anterior surface, posterior surface, and pancreatic transection margins should be described.

Type of Data: Primarily retrospective, low-level evidence.

Strength of Recommendation: Strong.

Rationale

The oncologic status of the surgical margins (R status) is generally—but not uniformly—regarded as a critical prognostic factor following pancreatectomy and is the most important such factor under the direct influence of the surgeon. For these reasons, the presence or absence of cancer cells at the surgical margins of transection is commonly reported as a primary metric with which the technical success of an individual operation is communicated to patients and other health care providers. The reported association between surgical margins and survival has led to the use of R status as a measure of surgical quality,25,26 an indicator of technical proficiency,27 a surrogate marker of the effect associated with preoperative treatment,28 and a key factor used to stratify patients enrolled in clinical trials of adjuvant therapies.29

Historically, cancer cells have been identified at the inked margins of 20% to 40% of surgical specimens resected from patients treated at single institutions30,31 and

within the context of major clinical trials.32 However, recent investigations that have used meticulous histopathologic protocols to critically evaluate pancreatectomy margins have demonstrated that cancer cells can be identified at one or more surgical margins in close to 90% of resected specimens, a rate that can more easily be reconciled with the reality that as many as 80% of patients who undergo curative resection for pancreatic cancer die with local recurrence.33,34 Therefore, whether a curative operation is reported as microscopically complete (R0) or incomplete (R1) may depend as much on the surgical pathologist as on the surgeon.

within the context of major clinical trials.32 However, recent investigations that have used meticulous histopathologic protocols to critically evaluate pancreatectomy margins have demonstrated that cancer cells can be identified at one or more surgical margins in close to 90% of resected specimens, a rate that can more easily be reconciled with the reality that as many as 80% of patients who undergo curative resection for pancreatic cancer die with local recurrence.33,34 Therefore, whether a curative operation is reported as microscopically complete (R0) or incomplete (R1) may depend as much on the surgical pathologist as on the surgeon.

Differences in the methods used to handle and process surgical specimens and to interpret and report pathologic findings may contribute to significant variability in R1 resection rates across populations.35 Because an inaccurate assessment of the surgical margins may alter the purported relationship between margin status and outcome, the utility of R status both as a robust technical metric and as a prognostic variable has been questioned. Furthermore, such variability may adversely influence the accuracy of assessments of patients’ eligibility for clinical trials of adjuvant therapies, the interpretation of the results of such trials, and ultimately oncologic outcomes. A discussion of the precise histopathologic protocols pathologists use to evaluate the status of pancreatectomy margins is beyond the scope of this book. However, surgeons play a critical role in certain aspects of the pathologic analysis of the surgical specimen, and these aspects are reviewed here.

Surgical Margins and Terminology

The seventh edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Cancer Staging Manual references the College of American Pathologists (CAP) Checklist for Exocrine Pancreatic Tumors as the standard document that should be used to guide pathologic evaluation of pancreatic resection specimens in the United States.36,37 This document does not specifically address differences between the handling or processing of pancreatoduodenectomy and distal pancreatectomy specimens. Rather, it lists the following margins and surfaces as important to evaluate when appropriate: the proximal (gastric or duodenal) and distal (jejunal) enteric margins, the pancreatic neck transection and bile duct margins, the deep retroperitoneal posterior surface, and the nonperitonealized surface of the uncinate process that lies adjacent to the SMA.

Among these anatomic components, the nonperitonealized uncinate surface of pancreatoduodenectomy specimens is emphasized by both the AJCC and CAP as having particular oncologic significance, as it is the most commonly positive margin following potentially curative resection and is the site of most local recurrences following the resection of cancers in the pancreatic head. Although the CAP guidelines refer to the corresponding tissue margin as the “uncinate process (retroperitoneal) margin,” the AJCC refers to it as the “SMA margin.” This inconsistency has further complicated the already confusing nomenclature used to describe the margin(s) that lie adjacent to the SMA and SMV, which have also been variably described as the “radial,” “deep,” and “posterior” margin(s), among other terms, by high-volume pancreatic cancer treatment centers.35

Furthermore, guidelines published by the Royal College of Pathologists promote a different nomenclature that is used by pancreatic surgeons and pathologists in

Europe.34,38,39 In this system, the anterior and posterior surfaces of the pancreatoduodenectomy specimen flank a medial “circumferential resection margin” (also described as the “vascular” or “superior mesenteric vessel” margin), which is composed of both an SMV groove margin and an SMA margin. As opposed to those published by the CAP, these guidelines describe in greater detail the important anatomic components of distal pancreatectomy specimens (e.g., inking the anterior and posterior surfaces is recommended specifically) and vein segments removed at pancreatectomy (e.g., examination of the proximal and distal ends of the resected vein is recommended). This lexicon and its accompanying analysis protocol were recently utilized in the first multicenter study to prospectively analyze margin involvement in pancreatectomy specimens.40

Europe.34,38,39 In this system, the anterior and posterior surfaces of the pancreatoduodenectomy specimen flank a medial “circumferential resection margin” (also described as the “vascular” or “superior mesenteric vessel” margin), which is composed of both an SMV groove margin and an SMA margin. As opposed to those published by the CAP, these guidelines describe in greater detail the important anatomic components of distal pancreatectomy specimens (e.g., inking the anterior and posterior surfaces is recommended specifically) and vein segments removed at pancreatectomy (e.g., examination of the proximal and distal ends of the resected vein is recommended). This lexicon and its accompanying analysis protocol were recently utilized in the first multicenter study to prospectively analyze margin involvement in pancreatectomy specimens.40

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree