Abbreviations

| CBD: | common bile duct |

| CT: | computed tomography |

| ERCP: | endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreaticography |

| IMA: | inferior mesenteric artery |

| IMV: | inferior mesenteric vein |

| MRI: | magnetic resonance imaging |

| PD: | pancreaticoduodenectomy |

| PPPP: | pylorus preserving proximal pancreaticoduodenectomy |

| PTC: | percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography |

| PV: | portal vein |

| SMA: | superior mesenteric artery |

| SMV: | superior mesenteric vein |

| SV: | splenic vein |

| TP: | total pancreatectomy |

| US: | ultrasound scan |

Approximately 6000 people die from pancreatic cancer in the UK each year. Second to colorectal carcinoma,it is the commonest cancer of the gastrointestinal tract and the fourth leading cause of cancer-related death at all sites. The incidence in Europe is 10–15 per 100 000 population per year. In the United States every year, 112 000 people die of gastrointestinal cancer and carcinoma of the pancreas accounts for 22% of these, making it the fifth leading cause of cancer death in the USA (1–3). Surgical resection offers the only chance of long-term survival, but the overall prognosis is poor. Pancreatic cancer accounts for the majority of pancreatic tumors (80%) but can be difficult to distinguish from other types of periampullary tumors on the basis of preoperative investigations and from unusual pancreatic primaries such as neuroendocrine neoplasms. Most of these other tumors have a much better prognosis than pancreatic cancer and the surgeon is usually faced with deciding about resection without definitive histologic guidance. Most pancreatic cancers (80%) are located in the head of the pancreas, but only 10–20% of these lesions are resectable at presentation and even fewer if the tumor arises outside the head. At the time of diagnosis, only 10% of patients have disease confined to the pancreas, while 40% exhibit local spread, and 50% distant disease.4

Surgery of the pancreas presents many technical challenges and is associated with a high morbidity rate for several reasons: (1) Patients are often elderly (80% between the ages of 60–80 years) and many have concomitant medical problems. (2) Despite substantial improvements, preoperative imaging may still leave doubt about the histologic nature of the tumor and the exact extent of the disease. (3) The pancreas is relatively inaccessible in its retroperitoneal location, being closely related to major vessels and other important viscera, which makes the approach and mobilization difficult. (4) The frequent presentation with obstructive jaundice results in potential problems with hepatic insufficiency, renal impairment, and coagulopathy. (5) Resection of the head of the pancreas requires a complex reconstruction with potentially disastrous complications if leakage occurs, particularly from the pancreatic anastomosis. (6) Patients have often lost a substantial amount of weight before operation and are consequently malnourished, which compromises their surgical recovery.

The treatment of pancreatic cancer has been dictated by the underlying philosophy of the physician/surgeon involved.5 Nihilists recommend a palliative approach for all patients, suggesting that the high operative mortality and morbidity rates cannot justify the dismal long-term outcome. Realists recognize the value of a resection when this can be achieved in a limited fashion but see no role for extending the operation beyond the pancreas. At the other end of the spectrum, activists recommend an extended pancreatectomy in the belief that they can achieve a curative resection. The nihilistic view is highlighted by claims that the overall number of five-year survivors is not significantly influenced by operation at all and that the number of those surviving without resection is similar to the number of those surviving with a resection.6

Patients with known hepatic or peritoneal disease are clearly incurable and resection of the primary tumor is of little or no value.7 No difference in survival times exist between patients with gross metastases detected at laparoscopy and those with positive cytologic test results but no visible metastatic disease.8 In the absence of symptoms such as gastric outlet obstruction, these patients are best palliated by nonsurgical means. On the other hand, patients in general good health who have a tumor that appears resectable on imaging should undergo exploratory laparotomy and possible resection since this represents the only chance of cure.9 The situation is more complex when the imaging suggests borderline resectability or when a less aggressive histologic type of tumor is suspected. A similar problem can arise during laparotomy when the surgeon finds that a previously considered “resectable” tumor is closely applied to adjacent structures and it is very difficult to differentiate tumor invasion from inflammatory adhesion.

The extension of pancreatectomy to include adjacent structures is controversial and detailed argument in support of the case is beyond the practical nature of this text, but situations may arise in which even conservative surgeons encounter tumor extension at a late stage of the operation and an extended resection becomes a reasonable option.

Preoperative Diagnosis and Staging

Preoperative Diagnosis and Staging

The appropriate diagnostic work-up of patients with suspected pancreatic carcinoma is a matter of debate, particularly the role of percutaneous biopsy in obtaining a histologic diagnosis before surgical intervention. Factors likely to influence this work-up include: the patient’s age and general health, the clinical presentation, the site of the tumor in the pancreas, the local expertise with various imaging modalities and the patient’s wishes. Spiral CT scanning is replacing angiography and even ERCP in many centers. The morbidity and mortality rate of major pancreatic resection is low today and most experienced surgeons will be comfortable with performing a resection without histologic confirmation. The potential complications associated with percutaneous biopsy of the pancreas are numerous, but in reality they occur very infrequently and the main disadvantage is the false-negative rate. This rate is higher with smaller lesions and these are the ones that are most likely to represent “curable” tumors. The occasional resection for benign pathology needs to be balanced against the tragedy of not resecting a potentially curable lesion. The old adage of not performing an investigation unless the result is likely to influence management holds true in the imaging of potentially resectable pancreatic tumors.

Somewhat paradoxically, a histologic diagnosis is more desirable in patients in whom operation is not likely to be an option, whether for tumor reasons or patient reasons. One always needs to be suspicious of very large or unusual pancreatic tumors, particularly those that are hypervascular or calcified on imaging. Pancreatic lymphoma is rare but eminently treatable, while neuroendocrine tumors of the pancreas also have a much better prognosis than that associated with adenocarcinoma. Biopsy of these large tumors should be straightforward and should yield an accurate diagnosis. If potentially toxic treatments are to be considered such as chemotherapy or radiotherapy, then a tissue diagnosis is essential.

Even small tumors of the pancreas will cause a surrounding area of inflammation and fibrosis that can lead to “sampling errors” when percutaneous biopsy is attempted. Thus, a negative biopsy for cancer certainly does not exclude cancer. In a resectable tumor, the occasional complication from percutaneous biopsy such as hemorrhage or pancreatitis can increase the technical difficulty of operation or even delay the procedure long enough for the tumor to progress to an irresectable stage. Percutaneous needle biopsy of the pancreas is a relatively safe and sensitive technique for establishing a histologic diagnosis, but it should generally be limited to patients with unresectable or metastatic tumors, many of which are sited in the body or tail of the pancreas. Percutaneous biopsy of pancreatic tumors potentially results in release of malignant cells and may affect the prognosis adversely as well as cause seeding along the biopsy tract.10,11 We would support percutaneous biopsy only in the setting of unresectable disease to confirm diagnosis or to determine whether a major resection would be worthwhile in the context of a large tumor that may have a less aggressive histologic pattern than “ordinary” ductal carcinoma of the pancreas.

The objective of imaging in pancreatic neoplasms is both to diagnose and stage the tumor and also to assess resectability. Tumor markers CA19-9 and CEA can be helpful to confirm clinical suspicion but are usually unhelpful in the context of patients with small and resectable tumors.12 Ultrasound scanning (US) is very good at detecting larger pancreatic neoplasms, but for lesions less than 1 cm in diameter computed tomography (CT) has a sensitivity of 79% compared to a sensitivity of 50% for ultrasound (13).13 Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) has a sensitivity of 96%,9 but the combination of clinical presentation, US and CT (without ERCP) allows an accurate preoperative diagnosis in more than 96% of patients.14 It is likely that ERCP will be required to make the diagnosis in a minority of patients, but it may clearly be helpful in relieving jaundice preoperatively; however, the placement of an endoscopic stent early in the patient’s work-up may impair the quality of CT images obtained with the stent in place. The role of angiography is debated: some authors report a greater accuracy in the detection of vascular involvement on CT than by angiography,15 while others suggest that angiography will detect vascular invasion in up to 31 % of patients reported as having negative CT scans.16 Angiography will detect vascular abnormalities in 30-45% of patients, but these can usually be identified during operation. Our policy is to perform angiography if the CT scan indicates a lesion lying close to the mesentericoportal venous trunk. Endoscopic US is reported to have 85% accuracy in assessing tumor resectability, but it is highly operator-dependent and is not yet widely available. Although magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) does not appear to improve on CT findings,17 the additional benefit of providing cholangiopancreaticographic and angiographic information from the single investigation promises an expanding role over the next few years. If involvement of adjacent organs such as stomach or colon is suspected, upper or lower gastrointestinal endoscopy helps to exclude full-thickness invasion, which may affect the decision to operate.

Role of Laparoscopy

Role of Laparoscopy

Advocates of laparoscopic staging suggest that more than 40% of patients with pancreatic cancer whose CT scan shows no evidence of distant disease will have metastases detected by this means.18 The incidence of peritoneal disease detected by laparoscopic staging of left-sided pancreatic carcinomas is reported to be as high as 53%.19 This technique is uniquely valuable at identifying peritoneal nodules. Others suggest that left-sided cancers are generally unresectable because of mesenteric axis infiltration; since this infiltration is not detected by routine laparoscopy, only 7% of patients will benefit from laparoscopy.9 We perform laparoscopy only if clarification is required for suspicious CT findings regarding distant metastases.

Preoperative Preparation

Preoperative Preparation

In patients with deep jaundice, particularly those with renal impairment or any suspicion of sepsis, we advocate a period of preoperative biliary drainage. The preferable route is with ERCP, but percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC) can successfully achieve internal drainage of bile in most cases. In patients with mild, uncomplicated jaundice it is reasonable to proceed to operation without decompressing the biliary tree, although in practice a stent has often been inserted before surgical referral at the time of diagnostic cholangiography.20

All patients for pancreatectomy should receive intravenous broad-spectrum antibiotics on induction of anesthesia and all will have subcutaneous low molecular weight heparin perioperatively. Jaundiced patients receive parenteral vitamin K and operation is usually delayed until the prothrombin time has normalized. Patients with tumors located in the body or tail of the pancreas, in whom splenectomy may be anticipated, are vaccinated prophylactically 2 weeks before operation against Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenza-B, and Neisseria meningitidis. If a colonic resection is suspected, particularly a left-sided resection,then osmotic bowel preparation is also given on the day before operation. Patients with recent jaundice are rehydrate don on the night before operation with intravenous fluids. Cross-matched blood is made available with a minimum of four units for a major pancreatic resection.

Materials

Materials

We use a general surgical instrument tray during the procedure but have available a vascular tray with a selection of straight and side-biting vascular clamps. The operating theatre is stocked with a range of prosthetic vascular grafts and appropriate vascular sutures. Our choice of incision is a bilateral subcostal or “gable” one and we prefer to use a fixed retractor system for displacing the costal margin.

Positioning

Positioning

The patient is placed in the supine position. Operation is commenced with a right subcostal incision for initial assessment. In the absence of gross signs of irresectability, the incision is extended to the left as necessary in a “gable” or “rooftop” fashion.

Technique

Technique

Basic Operative Approach

Basic Operative Approach

Although the major components of a pancreatic resection are traditionally described as “assessment,” “resection,” and “reconstruction,” in reality the first two steps are closely interwoven and a good deal of mobilization may be needed to complete a full assessment. Sometimes towards the end of the resection it becomes clear that a curative excision is not possible, yet so much of the resection has been performed that the operator is committed to completing what then becomes a palliative resection. Alternatively, the surgeon may elect to perform an extended resection in an attempt to clear all macroscopic disease.

The following description of operative technique will be based upon our “standard” pylorus-preserving proximal pancreaticoduodenectomy (PPPP) for tumors located in the head of the gland and will highlight the stages of the procedure at which further radicality/extension may be considered.21,22 These maneuvers will then be discussed in more detail. A later section will discuss the approach to pancreatic tumors located to the left of the portal vein. Underlying the overall approach to pancreatic surgery is the surgeon’s philosophy regarding the appropriate degree of radicality. Some surgeons set out to be very radical and will plan extended resections from the outset, while others will find themselves doing extended resections infrequently only after reaching the “point of no return” mentioned above. We acknowledge that all surgeons, regardless of their philosophy, may find themselves in the position to consider extension of the standard approach in certain situations and it is with this assumption that we proceed to describe how this might safely be accomplished.

Standard Pylorus-Preserving Proximal Pancreaticoduodenectomy

Standard Pylorus-Preserving Proximal Pancreaticoduodenectomy

Assessment

The first step is a detailed search for metastatic disease: hepatic metastases, lymph node deposits, peritoneal seedlings, and nodules in the omentum. The transverse colon and greater omentum are retracted upwards to expose the base of the transverse mesocolon and the area of the duodenojejunal flexure. Both are potential sites of tumor extension that will often suggest encasement of the superior mesenteric artery and irresectability. The dorsal surface of the stomach and the peritoneal surface of the lesser sac are also carefully palpated. In the case of neuroendocrine tumors, it is particularly important to examine the small bowel in some detail as the primary tumor may be identified, particularly in gastrinoma. The presence of metastatic disease is not necessarily a sign of irresectability. Some groups have advocated resection of liver metastases in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma,7,23 despite the generally poor prognosis in this group of patients. While noting this difference in surgical attitudes towards pancreatic tumors, we would not advocate resection of liver metastases in the setting of adenocarcinoma of the pancreas but certainly support this procedure in selected patients with neuroendocrine tumors.

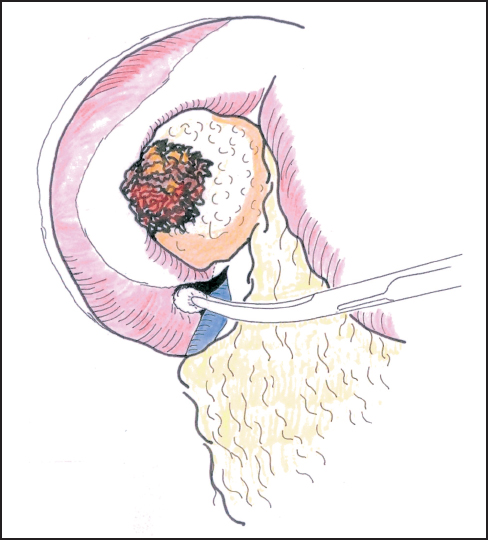

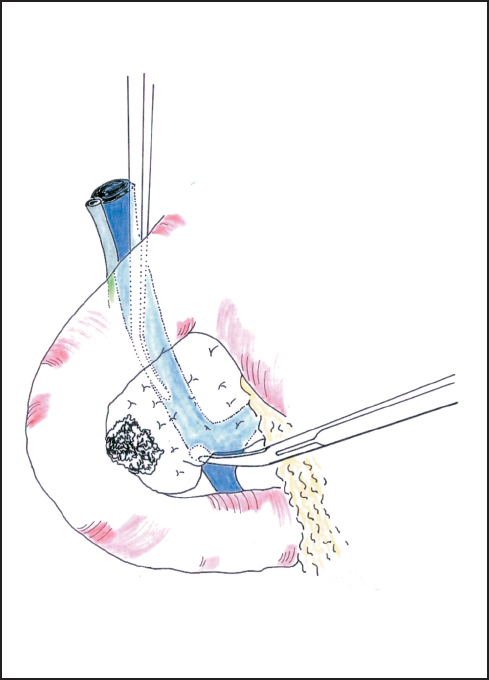

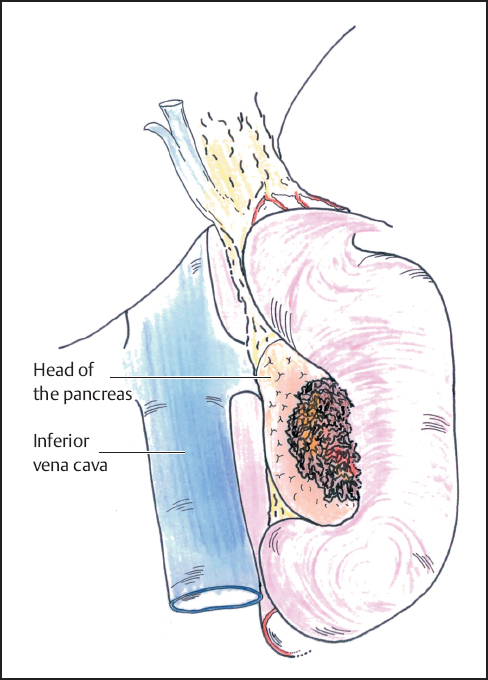

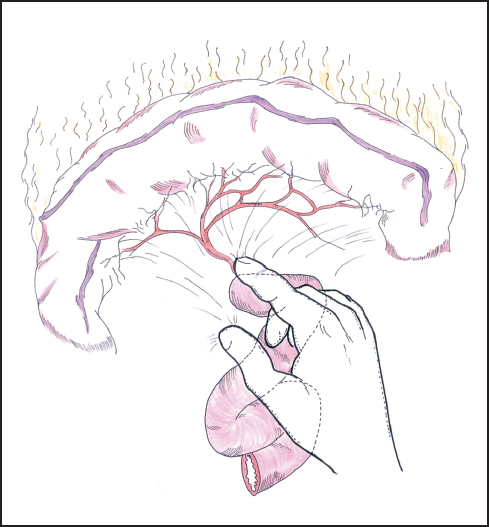

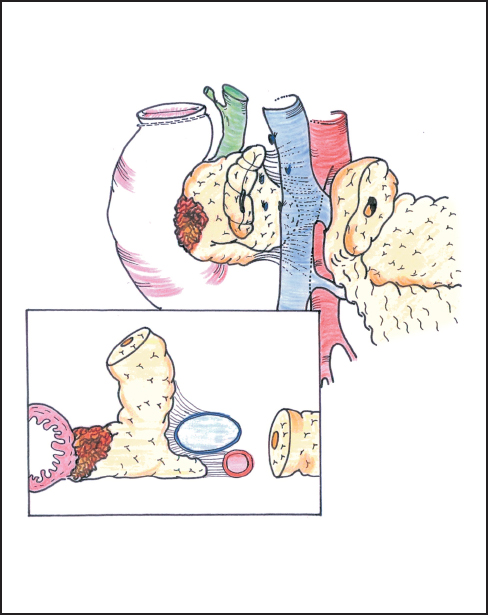

Mobilization of the head of the pancreas starts with the performance of a Kocher maneuver by incising the peritoneum along the lateral edge of the second part of the duodenum (Fig. 6.1). The hepatic flexure of the colon will sometimes need to be mobilized to achieve this step, but complete mobilization is usually only achieved once the lesser sac is fully opened. With the fingers of the left hand behind the pancreatic head and duodenum, the tumor is elevated to determine size, fixity, and invasion of contiguous structures, notably the portal and superior mesenteric veins (Fig. 6.2). At this point it may be possible to identify posterior fixity to the preaortic fascia, which is often heralded by back pain. It may be possible to develop a plane between the tumor and aorta in the case of peritumoral inflammation, but frank posterior invasion of the tumor precludes this step and makes the tumor irresectable. Pancreatic cancer spreads first along the nodes of the anterior and posterior duodenopancreatic grooves and then either along the hepatic artery to the nodes of the celiac axis or to the superior mesenteric nodes or both, depending on the position of the primary. Nodes adjacent to the pancreas can be resected en bloc and are generally included in a “standard” resection. The inclusion of distant nodes is controversial and is covered below as one possible type of extension.

Fig. 6.1 Incision of the posterior peritoneum and blunt dissection of the second duodenum.

Fig. 6.2 The head of the pancreas is mobilized by incising the peritoneum along the lateral edge of the second part of the duodenum (Kocher maneuver). After full mobilization of the duodenum and head of the pancreas it is possible to palpate the periampullary area to assess the relationship of the tumor to the portal and superior mesenteric veins and the superior mesenteric artery.

Fig. 6.3 The lesser sac is entered by elevating the greater omentum and developing the avascular plane between it and the transverse colon, thus exposing the body of the pancreas.

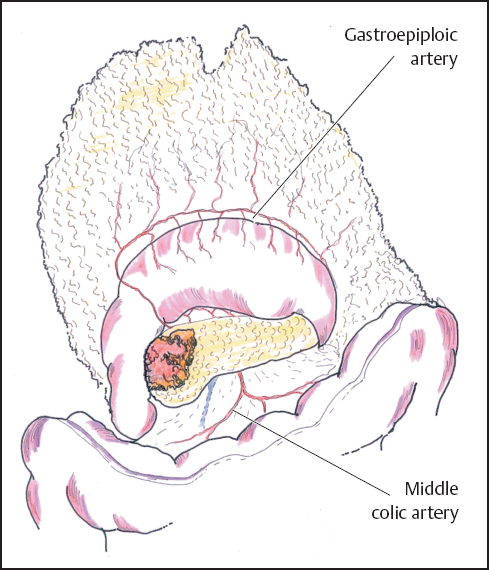

Once obvious signs of irresectability have been excluded in the form of extensive local invasion or remote metastases, further assessment takes the form of a trial dissection. Much of the necessary mobilization can be achieved without irreversible commitment to a resection. At this point the lesser sac is widely entered by developing the avascular plane between the transverse colon and the greater omentum, keeping well clear of the gastroepiploic vascular arcade (Fig. 6.3). Infrequently sizeable veins cross this “avascular” plane and require formal ligation, but most of the dissection can be usually performed with diathermy. Dissection of the greater omentum is continued to the right to mobilize the hepatic flexure of the colon and to the left as far as necessary to expose the neck and body of the pancreas. The tumor may occasionally involve the right colon or its mesocolon by direct tumor invasion or inflammatory adherence. The nature of this involvement may be difficult to determine and en bloc resection of the right colon may then be required (see below).

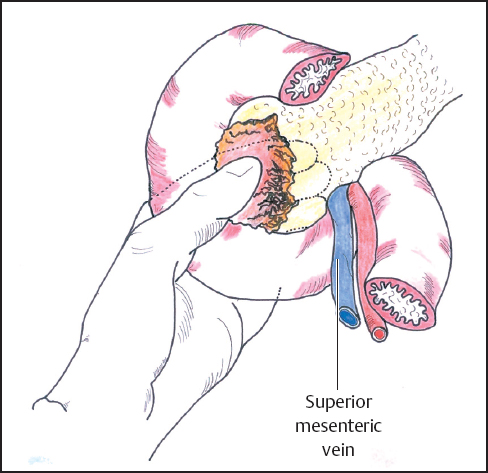

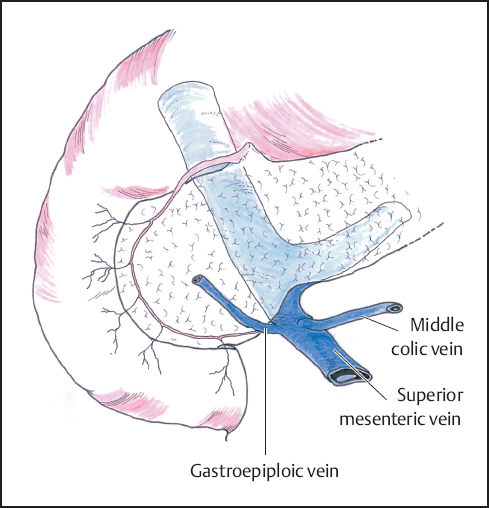

The stomach and attached greater omentum are retracted upwards and the transverse mesocolon is drawn downwards to expose the lower edge of the pancreatic neck. The middle colic veins are identified and followed as a guide to the superior mesenteric vein below the neck of the pancreas and the peritoneum over the vein is carefully incised to expose the vessel wall (Fig. 6.4). Gentle blunt dissection is employed to develop the tunnel between the portal vein and the neck of the pancreas. It may help to divide the right gastroepiploic vein and artery on the pancreas and below the first part of the duodenum to facilitate this exposure, but this step has no adverse consequence if resection is not in fact performed. In some instances it may be quicker and safer to identify the portal vein by approaching it in the lateral groove between the uncinate process and the third part of the duodenum as an extension of Kocher‘s maneuver (Figs. 6.5, 6.6), but often it is the clearance of the right lateral border of the portal vein that is most in doubt and a plane may be difficult to develop (Fig. 6.7).

Fig. 6.4 The superior mesenteric vein is identified at the inferior border of the pancreas. Care must be taken not to damage the middle colic and gastroepiploic veins that enter the superior mesenteric vein at this point.

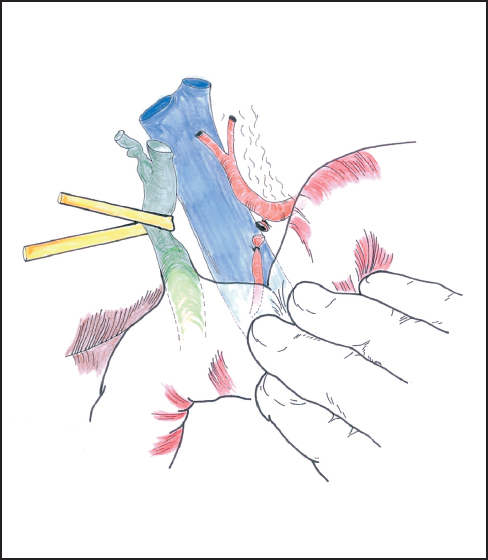

If the portal vein tunnel is difficult to develop from below, it may be safer to expose it from above. The peritoneum of the lesser omentum/gastrohepatic ligament is divided to enter the lesser sac from above. The hepatic artery is located, being usually marked by a lymph node or nodes at this site. The artery is traced proximally and distally for a short distance to identify the origin of the gastroduodenal artery, which arises from a “genu” or right-angled bend on the hepatic artery. The gastroduodenal artery is ligated and divided at this point. The hepatic artery is now slung and retracted cephalad to expose the portal vein below. This maneuver is facilitated by dissecting the common bile duct (CBD) and passing a sling around this structure to retract it laterally (Fig. 6.8). The plane between the portal vein and the neck of the pancreas is further developed. No major tributaries enter the anterior surface of the portal vein in this area and as long as the dissection does not stray from this plane, bleeding is not usually a problem. At this stage it should be becoming clear how the portal vein is related to the tumor and thus whether resection is a possibility. If a surgical palliative bypass is to be completed in any case, then it may be appropriate to divide the CBD at this point to improve access and allow further assessment of the relationship between the tumor and the portal vein. A swab of bile is taken for culture and any indwelling stent is removed and also sent for microbiological examination.

Fig. 6.5 The superior mesenteric vein is approached between the uncinate process and the third duodenum.

Fig. 6.6 Complete mobilization of the duodenum and head of the pancreas is shown (Kocher maneuver).

Fig. 6.7 Gentle blunt dissection is employed to develop the tunnel between the portal vein and the neck of the pancreas. The tunnel between the portal vein and the neck of the pancreas is established and the passage of a sling often aids further dissection.

Fig. 6.8 The gastroduodenal artery is securely ligated before division. As the bile duct is retracted laterally, the suprapancreatic portion of the portal vein is exposed.

Fig. 6.9 The bile duct is divided just above the entry of the cystic duct. The duodenum is stapled after the pylorus.

Fig. 6.10 The root of the transverse mesocolon and the area around the duodenojejunal flexure are further assessed for tumor invasion.

Although there is no clear oncological benefit in removing the uninvolved gallbladder, we generally complete a retrograde cholecystectomy and divide the bile duct at the point of entry of the cystic duct (Fig. 6.9). Removing the gallbladder should allow for a higher division of the bile duct, thus clearing more nodal tissue, avoiding the problem of an ischemic stump and future potential problems with gallstones and cholecystitis due either to tumor invasion of the cystic duct or as a consequence of any adjuvant chemotherapy. In practice, however, experience with preservation of the gallbladder in pancreaticoduodenectomy for chronic pancreatitis or less aggressive periampullary tumors has shown little or no ill effect from such a maneuver.22

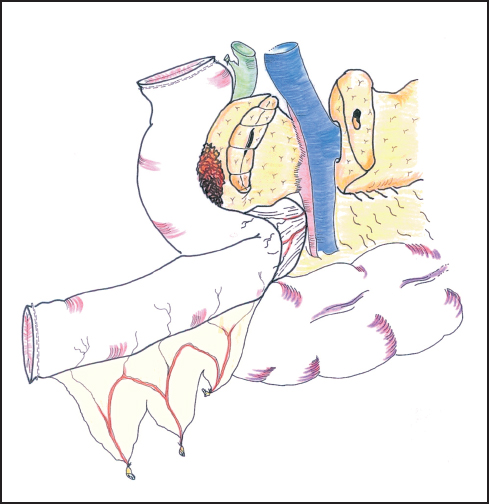

Attention is now turned to the duodenojejunal flexure, where the fourth part of the duodenum is further mobilized by dividing the ligament of Treitz to assess the tumor relationship to the SMA (Fig. 6.10). If resection looks feasible, then it is reasonable to divide the first part of the jejunum and begin mobilization of the proximal portion by dividing the jejunal and duodenal branches of the SMA close to the bowel wall, taking care not to damage the main vessel or the adjacent inferior mesenteric vein. This maneuver represents an irreversible step as the jejunum quickly becomes ischemic and will need to be resected in any case. Jejunal transection can be delayed until after division of the pancreas, but in reality the resectability or otherwise of the tumor is usually evident by this stage of the assessment. We tend to mobilize the jejunum and fourth part of the duodenum as much as possible from below the transverse mesocolon as the access and exposure allow this to be achieved more easily than from above, although the dissection can proceed from both aspects according to satisfactory progress.

Resection

The boundary between assessment and resection becomes blurred at this stage of the procedure, but it is now that a decision needs to be made on the resectability of the tumor and whether the antrum and/or portal vein are to be resected. For a carcinoma arising in the upper head of the pancreas close to the pylorus or duodenal cap, a formal Whipple procedure incorporating distal gastrectomy will be needed. For lesions of the lower pancreas head or uncinate process, we generally favor a pylorus-preserving resection but perform frozen section histology of the duodenal resection margin. Should the result (exceptionally) be positive for carcinoma, or should we feel that tumor clearance might be compromised in any way, we have little hesitation in resecting the antrum of the stomach (see below). The first part of the duodenum is mobilized from the pancreas by securing several small vessels that run between the two organs thereby allowing division of the duodenum by stapling or between fine clamps about a few cm distal to the pylorus (Fig. 6.11). The distal end is oversewn and the proximal end is tucked away into the left upper quadrant, taking care not to damage the spleen. The stomach is emptied by suction and the duodenal cap is then surrounded by a swab soaked in antiseptic solution if occluded by tissue forceps. If stapled the duodenal stump is simply rubbed with an antiseptic swab. It is important to maintain an adequate blood supply to the pylorus and in the absence of the gastroduodenal artery, the blood supply is dependent on the gastroepiploic arcade which should be preserved on the greater curve of the stomach. This is another reason for elevating the greater omentum off the transverse colon rather than entering the gastrocolic omentum directly.

Fig. 6.11 The bile duct is divided at a convenient point, usually above the cystic duct. This provides further access to the portal vein.

Fig. 6.12 The neck of the pancreas is divided between hemostatic stay sutures. Care is taken to protect the portal vein at this point.

Fig. 6.13 With the operator’s left hand behind the head of the pancreas, the plane between the pancreas and portal vein is gently developed, ligating any vessels that are encountered. Excessive traction may pull the superior mesenteric artery to the right of the portal vein and place it at risk during dissection.

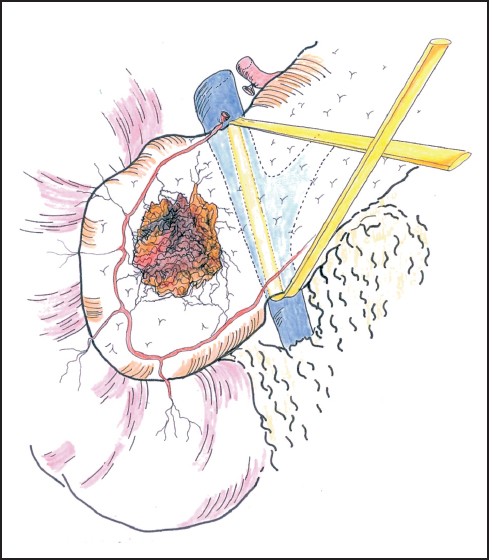

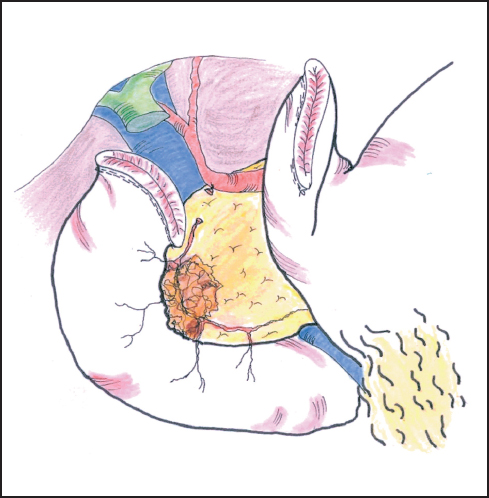

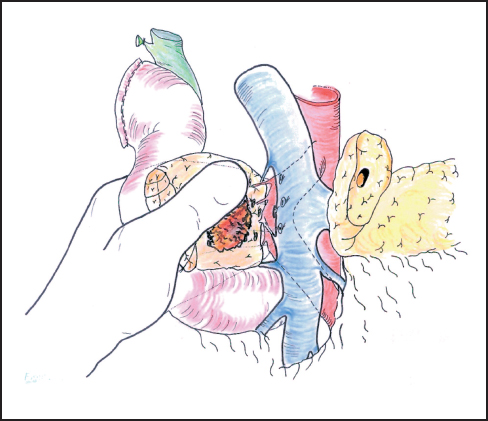

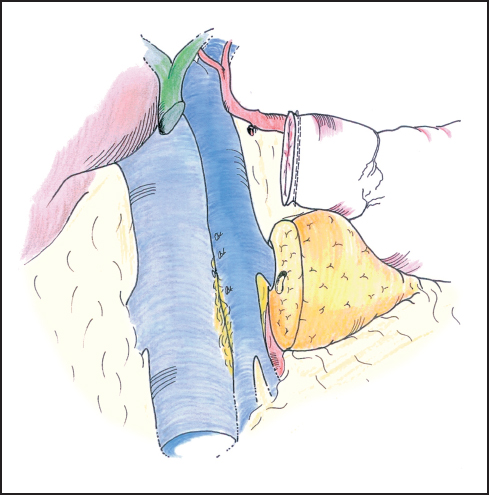

Our standard approach is now to divide the neck of the pancreas, which has been clearly exposed by retracting the stomach to the left (Fig. 6.12). In some instances the portal vein can be resected at this point and this maneuver is described below. A Kocher’s grooved director is inserted along the portal vein tunnel and stay sutures are inserted into the inferior and superior margins of the neck of the pancreas on either side of the line of anticipated division partly to enclose small arteries running on the surface of the gland and partly to facilitate retraction. The neck of the pancreas is now divided. We prefer to use a scalpel as it allows clear visualization of the pancreatic duct and makes frozen section examination of the cut surface easier to interpret without diathermy artefact. If frozen section is positive, then we consider extending the pancreatectomy or completing a total pancreatectomy (see below). Frozen section is used in this way by other groups.24–27 The head of the pancreas and duodenum are now supplied only by a few tributaries of the portal vein and the duodenal branches of the second/third part of the duodenum. With the operator’s left hand behind the head of the pancreas and with aid of a small swab, the right hand is used to sweep the portal vein gently off the pancreas, ligating any vessels that are encountered (Fig. 6.13). The venous drainage is relatively constant and comprises an upper pole vein and two-to-three inferior pancreatic veins; they are fragile and need to be encircled and ligated with care. The left hand in this position allows palpation of the SMA to make sure it is not included in ligatures and it also allows for control of the portal vein if hemorrhage is encountered. It is necessary to divide the roots or “crura” of the pancreas, i.e., the tough connective tissue that binds its deep surface to the preaortic fascia (Figs. 6.14, 6.15). Leashes of tissue are encircled with a right-angled forceps and are ligated and divided. One or more of these tissue leashes will include SMA branches, i.e., inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery or arteries, but if they are all ligated then bleeding should not occur. The dissection is carried out just beyond the border of the pancreas (which is recognized by its lobular appearance) unless the tumor appears to be infiltrating in this region or a decision is taken to skeletonize the SMA. Pulling the mobilized proximal jejunum through the congenital mesocolic window into the supracolic compartment often helps orientation and clarifies the appropriate place for jejunal division, which is usually 20-30 cm beyond the duodenojejunal flexure (Fig. 6.16). It is during this final dissection that the detailed relationship between tumor and portal vein becomes apparent. A degree of “adhesion” often exists and it can be difficult to decide between tumor invasion and inflammatory change. This part of the operation is time-consuming and care must be taken to achieve hemostasis (Fig. 6.17). The indication and technique for resection of the portal vein are described below if this maneuver is to be included.

Fig. 6.14 The deep part of the pancreas is bound down by fascia surrounding the aorta and superior mesenteric artery. This usually needs to be divided between ligatures.

Fig. 6.15 The frontal view and cross-section show how the deep part of the pancreas is closely bound to the superior mesenteric artery by tough connective tissue and requires retraction of the margin of the portal vein for full exposure.

Fig. 6.16 The first jejunal loop is passed through the mesocolic window on the right of the superior mesenteric vessels.

Fig. 6.17 Once the specimen is resected the deep attachments of the pancreas head can be inspected for final hemostasis.

Reconstruction

Several methods of reconstruction are possible, each with its own advocates and none of proven superiority. The most important points are technical skill in creating the several anastomoses and adherence to surgical principles of good blood supply, freedom from tension, and careful hemostasis. The pancreatic anastomosis is the Achilles’ heel of pancreaticoduodenectomy and a greater impact on postresection survival can be made by reducing the operative mortality rate than by the application of extended resection or adjuvant treatments. Our preference is to commence by joining the pancreatic neck to the upper jejunum, end-to-end, followed by the bile duct anastomosis, and finally the duodenoenterostomy, as described previously.28 The jejunum is usually delivered to the supracolic compartment through the congenital tunnel behind the superior mesenteric vessels but in certain cases, for example a tumor of the uncinate process, it may be better to use a separate right-sided mesocolic window.

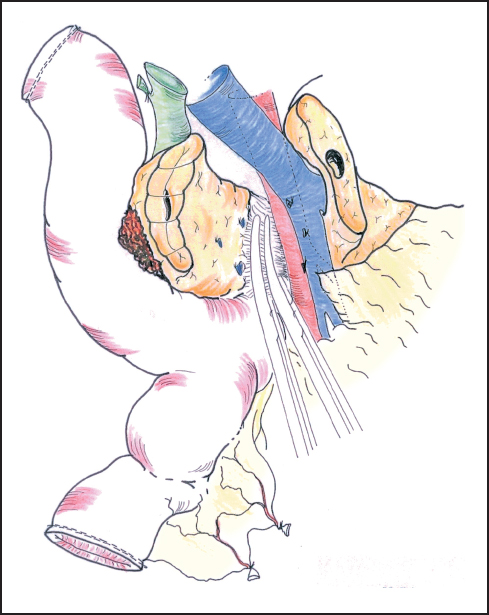

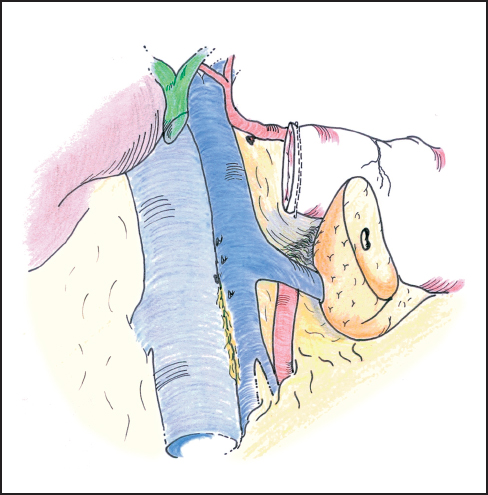

The two-layer pancreaticojejunostomy is facilitated by mobilizing the posterior surface of the proximal body of the pancreas off the splenic vein for a distance of 3–4 cm, carefully dividing between ligatures one or more tributaries of the splenic vein (Fig. 6.18). The exact technique employed depends on the disease process and consequently the calibre of the pancreatic duct and the nature of the pancreatic parenchyma: soft glands with small ducts require an invaginating or “dunking” type of anastomosis with a supporting stent, while glands with dilated ducts and firm parenchyma can be sutured directly mucosa-to-mucosa with the jejunum. However, in every case it is appropriate to have at least some of the sutures incorporate ductal mucosa and to include an outer layer of invaginating sutures.

Fig. 6.18 The pancreatic anastomosis is facilitated by mobilizing the posterior surface of the proximal body of the pancreas off the splenic vein for a distance of 3–4 cm.

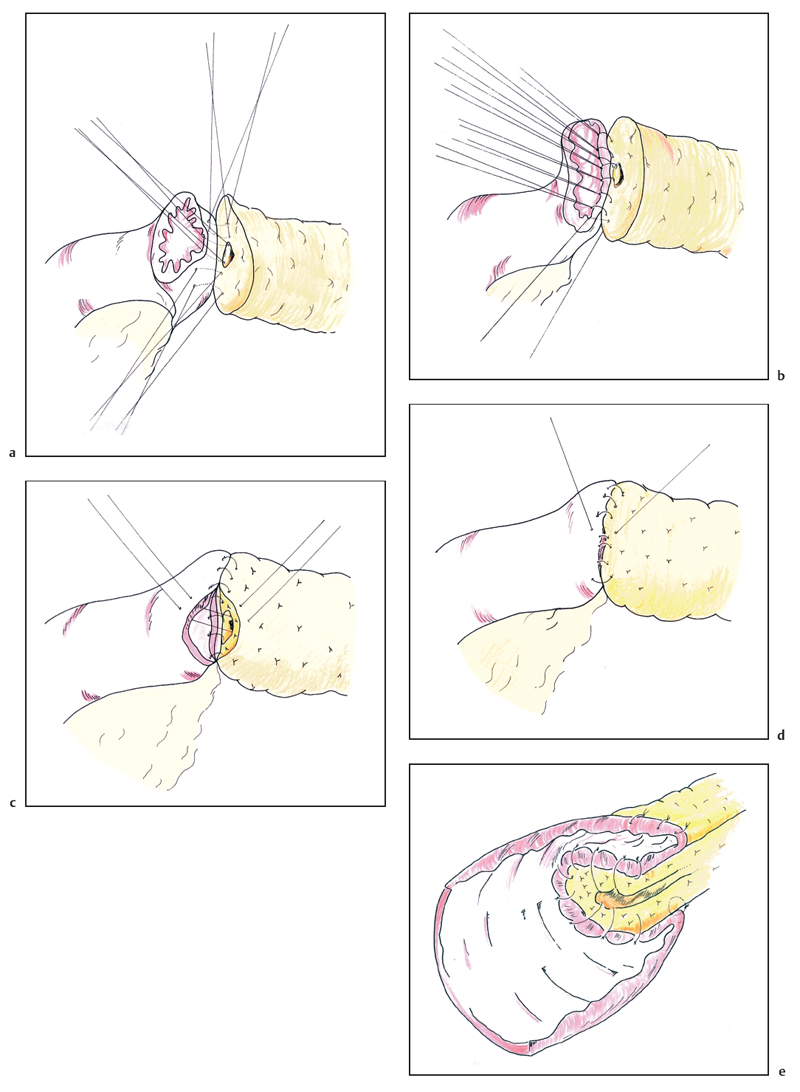

The end-to-end invaginating anastomosis is carried out using two layers of interrupted nonabsorbable (3–0 silk) sutures. However, some authors perform the entire anastomosis with 4–0 or even 5–0 PDS absorbable sutures. Initially, a few anterior sutures are placed through the pancreatic parenchyma so as to emerge from the duct and these are held in hemostats; if the duct is small this may be the only opportunity to suture its mucosa anteriorly (these sutures are represented on Fig. 6.19a,b). Then a first posterior row of inner sutures is placed between the pancreatic duct (and pancreatic parenchyma outside the duct) and the seromuscular layer of the jejunum. When meeting the duct, the full thickness of the jejunum is taken (Fig. 6.19 a). In this posterior row, the sutures are first inserted then tied up. The second inner layer incorporates the pancreatic parenchyma and the full thickness of the small intestine (Fig. 6.19 b). The sutures must be tied with great care to avoid them cutting through the pancreatic tissue and causing troublesome bleeding halfway through construction of the anastomosis. The anterior inner layer then unites the cut surface of the pancreas and its duct to the full thickness of the jejunum (Fig. 6.19 c) and the outer layer of sutures is placed between the seromuscular coat of the bowel and the fibrous pancreatic capsule, drawing the jejunum over the inner anastomosis like a sheath; this second layer should be placed approximately 1 cm beyond the first layer so as to ensure sufficient tissue for invagination (Fig. 6.19d). Although each individual outer suture only draws the jejunum over by a small amount, with care and progressive suturing, it is eventually possible to “bury” the inner layer 1.5-2 cm within the outer layer (Fig. 6.19e). We attempt to incorporate the duct mucosa in as many inner sutures as possible and even in very small ducts find that 3-4 sutures can be placed in this fashion both anteriorly and posteriorly. When concerned about patency of the pancreatic duct, we place a trans-anastomotic stent in the form of a pediatric feeding tube (6 or 8 Fr) across the anastomosis (Fig. 6.20a,b). The tube is first passed through the abdominal wall and then along the jejunum, entering some 30 cm distal to its cut end. The tube is passed up the pancreatic duct, if possible for 5-10 cm. The stent is anchored within the pancreatic duct using an absorbable suture (4-0 PDS) before completing the anastomosis. The stent is pierced by one needle of a double-ended suture and each needle is brought out through the duct and the pancreatic tissue so the suture can be tied over a small buttress of muscle taken from the rectus abdominus (Fig. 6.20c). Using this technique we have reported a pancreatic leak rate of 4%.21 The stent is then exteriorized and the jejunum around the stent exit point is ultimately sutured to the peritoneum of the anterior abdominal wall. The stent can be clamped (with or without tubography) after the early postoperative phase and it is removed before the patient’s discharge or at an early outpatient follow-up visit.

Fig. 6.19 The pancreaticojejunal anastomosis is commenced by placing the inner layer of sutures, incorporating the pancreatic duct in as many sutures as possible (a, b). The anterior wall is completed in a similar fashion, again attempting to place several sutures into the pancreatic duct (c). The second layer of sutures between the seromuscular layer of the jejunum and the fibrous capsule of the pancreas progressively buries the inner layer (d) to result in a two layer anastomosis (e).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree