Palliation:Brain, Spinal Cord, Bone, and Visceral Metastases

CEREBRAL METASTASES

Natural History

Annual incidence of approximately 170,000. Metastatic brain tumors outnumber primary brain tumors by a factor of 10 to 1.

The patient has a median survival of 3 months.

Many signs and symptoms will respond to steroids within 48 hours.

Headache and impaired cognition are the most common symptoms.

The most common anatomic primary sites are breast and lung.

Except for choriocarcinoma, metastases to the brain from cancers of the urogynecologic region or gastrointestinal tract are uncommon.

Melanoma has the highest percentage of brain metastases relative to other primary sites.

Hemorrhagic metastases are commonly seen from renal cell carcinoma, choriocarcinoma, and melanoma

“Single” brain metastasis describes one brain metastasis in the setting of other sites of disease.

“Solitary” brain metastasis describes one brain metastasis in the setting of no other sites of disease.

Diagnostic Workup

Magnetic resonance imaging with gadolinium can detect multiple metastases and leptomenin-geal invasion more effectively than any other imaging technique.

When a single, first suspected metastatic lesion is detected, histologic confirmation should be obtained.

Prognostic Factors

Both performance status and extent of extracranial disease have been shown to impact prog nosis. Three RTOG brain metastases studies involving 1,200 patients were used to develop a recursive portioning analysis (RPA). Three RPA classes were described: RPA class I (Karnofsky

performance score [KPS] > 70, controlled primary, age less than 65 years, brain metastasis only), II (not meeting requirements of classes I or III), and III (KPS less than 70) having median survivals of 7.1,4.2, and 2.3 months, respectively (10).

A computed tomography (CT) review of 779 patients with cerebral metastases showed no imaging characteristic that predicted a prolonged median survival after irradiation (39). In 79% of patients who presented with one to three lesions on the pretreatment CT scan, the median survival was 4 months, compared with 3.2 months in the remaining 21% who had four or more lesions.

General Management

Corticosteroids are recommended to improve neurologic function, but neither survival nor length of response is affected.

A reasonable corticosteroid regimen in patients with brain metastases is a 10-mg intravenous or oral bolus of dexamethasone, followed by 4 to 6 mg every 6 to 8 hours for an appropriate period of time, followed by a taper.

In an asymptomatic patient with little peritumoral edema or mass effect, corticosteroids may be reserved until the first sign of neurologic symptoms.

The median survival in patients treated with steroids alone is 2 months; adding radiation therapy extends the median survival to 3 to 5 months. Selected patients with solitary metastasis who have good performance status, no meningeal involvement, and no extraneurologic disease (or very limited extraneurologic disease that has responded to systemic therapy) may have a median survival of greater than 12 months (8, 24).

Metastasis to the cerebellum, causing severe ataxia, or a large single cavitating metastasis in the cerebral hemisphere, is occasionally best palliated by excision.

In 1,506 patients managed by surgery and irradiation who were compared with 2,724 patients treated with radiation therapy only, the median survival was similar at 6 months, but the 1-year survival was doubled for the combined-modality series (41).

In two randomized RTOG studies comparing several fractionation schedules and total doses of radiation (20 Gy in 5 fractions to 40 Gy in 20 fractions), improvement in neurologic function, duration of improvement, time to progression, and survival were the same in the various groups (6).

Cancer of the breast is the most common primary site to metastasize to the orbit or choroid, potentially causing proptosis and diplopia. If the orbital metastasis is solitary or the recurrencefree interval is greater than 3 years, a dose higher than 30 Gy given over an interval greater than 2 weeks may be indicated. The base of the skull must be evaluated carefully for associated lesions.

Radiation Therapy Techniques

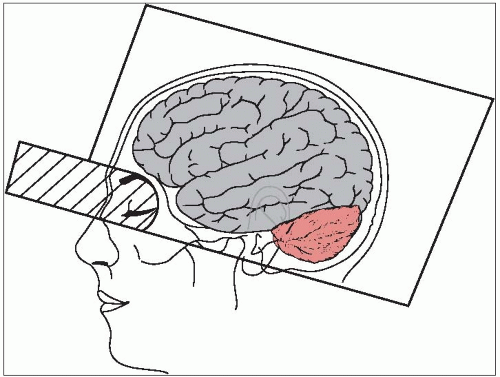

For whole-brain radiation therapy (WBRT), opposed fields covering all cranial contents that flash the calvarium and extend inferiorly, stopping at a border delineated by the supraorbital ridge to the mastoid, can easily be used in a cooperative patient.

If the lesion is in the inferior portion of the frontal or temporal lobe, the portal must descend to the infraorbital ridge and the external auditory meatus (Fig. 51-1). A lens block or a fixed shield defining the skull base may be considered in this case.

Patients who respond to 20 Gy in 4 or 5 fractions or 30 Gy in 10 to 12 fractions and have a recurrence can be treated again with 25 Gy in 10 fractions.

Postoperative whole-brain radiation for solitary brain metastases was shown to reduce disease recurrence not only at the site of initial disease but also elsewhere in the brain in a prospective randomized trial (26).

Radiosurgery

Although no randomized trials have been performed comparing surgery with stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS), they both have similar local control rates when combined with WBRT.

Radiosurgery can easily treat subcortical and deep lesions, as well as those in other critical (eloquent) brain areas (e.g., sensorimotor, language, and visual cortex; hypothalamus and thalamus; internal capsule; brainstem; cerebellar peduncles; deep cerebellar nuclei).

The first randomized trial reporting the benefit of SRS after WBRT was by Kondziolka et al. (17). This small study was stopped early because of a large difference in local control in favor of SRS (92% versus 0% p = 0.0016). There was a nonsignificant overall survival benefit in the SRS group.

RTOG 95-08 was a prospective randomized control trial that compared WBRT plus SRS to WBRT alone in patients with one to three brain metastases. Overall survival was not statistically different between the WBRT plus SRS and WBRT alone arms (6.5 and 5.7 months, respec tively;ˆ = 0.1356), except on subgroup analysis of those patients with single metastasis who dem onstrated a survival benefit with the addition of SRS. Overall, local control was higher in the SRS boost arm; this did not, however, translate into a lower death rate from neurologic progression. An overall survival benefit with SRS boost was found in several subgroups that included patients with RPA class 1, tumor size > 2 cm, and metastases from non-small cell lung cancer (2).

Sneed et al. reviewed data on newly diagnosed brain metastases managed initially with SRS alone versus SRS + WBRT from ten different institutions. No difference was found in overall survival by RPA class. Freedom from relapse was worse without WBRT but that difference disappeared after first salvage therapy (37).

The maximum tolerated dose for single fraction radiosurgery in the setting of brain metastases was demonstrated by the RTOG to be dependent on the size of the brain metastasis: tumor diameter less than 20 mm, dose 24 Gy; diameter 21 to 30 mm, dose 18 Gy; diameter 31 to 40 mm, dose 15 Gy (35).

The 50% isodose line is the prescription line typically used for Gamma Knife SRS, but the approximately 80% isodose line is used for linear accelerator-based SRS.

In 1,281 patients from ten institutions treated by radiosurgery, the dose varied by a factor of 2 (16 to 29 Gy), but the percentage control was similar (approximately 90%) (15).

SPINAL CORD COMPRESSION

Natural History

Of 100 patients with spinal cord compression, the radiation oncologist will complete treatment on 60; 20 patients will progress during irradiation, and 20 will not be referred either because of paraplegia with sphincter paralysis or early death (38).

Prognostic Factors

The most important prognostic factor is ambulation (1). Patients who are ambulatory after treatment have a median survival of 8 to 9 months, whereas median survival is 1 month for nonambulatory patients.

Clinical Presentation

Most patients who present with metastatic spinal cord compression have endured back pain for weeks.

The most common site for cord compression is the thoracic spine.

In 610 patients with small cell lung cancer, bony metastases were associated with less than 5% of patients with clinical cord compression (11).

Diagnostic Workup

Magnetic resonance imaging is the most informative study in the evaluation of suspected metastasis to the epidural space. If it is a first metastatic lesion, histologic confirmation should be obtained, unless medically contraindicated.

General Management

Radiotherapy, surgery, or a combined-modality approach constitutes the management for spinal cord compression.

Patchell et al. (27) demonstrated in a prospective randomized trial of surgery with postoperative RT compared with RT alone that surgery followed by postoperative RT improved survival and ambulation. Patients who received postoperative RT regained the ability to walk more often, retained their ability to walk longer, and required less steroid and pain medication.

An operative procedure should especially be considered for fracture/dislocation/mechanical instability, acute-onset paraplegia, radioresistant lesions, absence of steroid response, and/or if there is no histologic proof of metastatic cancer (19).

A starting dose of 10 to 20 mg of dexamethasone, i.v. or p.o., followed by 4 to 6 mg q.i.d. relieves pain and improves neurologic symptoms in many patients.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree