Pain Management

Pain can significantly decrease patients’ quality of life during and after radiotherapy, but appropriate and adequate pain management remains imperfect. More than half of patients who undergo radiotherapy experience pain,1 and the majority of patients and physicians feel that patients’ pain is inadequately controlled.2

Pain may result from tissue damage caused by the tumor, such as bone destruction by a metastasis from prostate cancer or invasion of the celiac plexus by pancreatic cancer, or from the delivery of radiotherapy and subsequent complications. Irradiation of normal tissues, especially those with a rapid growth turnover rate, causes cell death and triggers a cascade of proinflammatory cytokines and thrombotic and growth factors, propagating local painful reactions.3,4 Radiation oncologists must be knowledgeable about pain management during and after radiotherapy. In this chapter we discuss the pathophysiology of pain, treatment options, and practice guidelines for developing a stepwise, integrated treatment plan.

Radiotherapy is also a valuable modality in the treatment of cancer pain. It is commonly used in the palliative setting when a radiosensitive cancer invades bone, soft tissue, or nerves.5 Radiotherapy for the palliation of pain caused by various types of cancer is covered in their respective chapters elsewhere in this book.

TYPES OF PAIN

TYPES OF PAIN

Pain generally can be defined as either nociceptive or nonnociceptive. Nociceptive pain refers to the nervous system response that is proportionate to the tissue damage initiating the response. Nociceptive pain is divided into somatic pain and visceral pain, depending on the location and symptoms of the painful stimulus. Typically, somatic pain presents as a well-localized sharp, stabbing (knifelike), and achy pain as a response to skin, muscle, and connective tissue damage. Conversely, patients typically find it difficult to localize visceral pain, which also may have a somatic referral pattern, often complaining of cramping or a dull ache.6

Nonnociceptive pain encompasses both neuropathic and psychogenic (or idiopathic) pain syndromes. In these cases, nervous system responses are not what would be expected from the damage causing the response. In fact, responses may occur without tissue damage. Neuropathic pain involves abnormal pain processing by the peripheral or central nervous system. Patients may complain of burning, shooting, tingling, or numbness, which generally occurs along a nerve distribution.7 Patients also may experience pain that is out of proportion to physical injury. Psychogenic causes such as depression and anxiety may exacerbate the perception of painful stimuli.

Understanding a patient’s symptoms allows the physician to determine the pathophysiology of the pain syndrome. Each type of pain syndrome is amenable to treatment with different modalities. For example, somatic pain, localized sharp pain, may be better treated with opioid medications, whereas anticonvulsants or antidepressants may be more effective against neuropathic pain. Other modalities, such as acupuncture, have been shown to help either type of pain.8

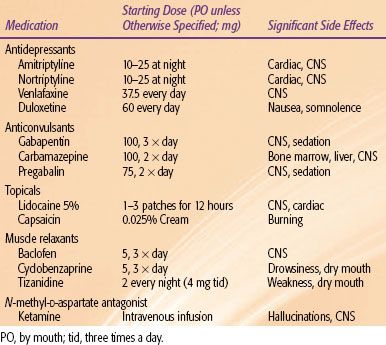

FIGURE 96.1. World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines for initial medical treatment for cancer pain. A three-tiered system broadly indicating the use of opiate medications for continued pain control is shown. As pain symptoms worsen, a physician may enter a higher tier of medications for pain control. (Adapted from World Health Organization. WHO guidelines cancer pain relief, 2nd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1996.)

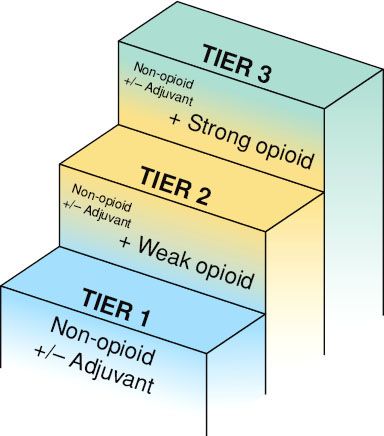

TABLE 96.1 GUIDE TO COMMON NONOPIATE MEDICATIONS AND STARTING DOSES FOR ADULTS

MEDICAL MANAGEMENT

MEDICAL MANAGEMENT

Many national and international organizations have developed guidelines for pain management. Despite variations in the details, the principles and approaches are consistent across guidelines. The World Health Organization (WHO), American Pain Society (APS), and National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines are discussed here.

WHO Pain Ladder

The WHO guidelines for analgesic management of cancer pain, first described in the early 1980s,9,10 consist of a three-step approach that has been validated in recent trials.11 Despite some debate on its effectiveness,12 it establishes a widely practiced, stepwise approach in the treatment of various levels of pain severity.

The first tier involves the use of nonopiate medications, primarily nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (Table 96.1). These medications include acetaminophen, nonspecific cyclo-oxygenase inhibitors (including ibuprofen, diclofenac, aspirin), and cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors (celecoxib).13 NSAIDs are considered the first group of medications to administer. If the patient’s pain persists or worsens, the second tier adds a weak opioid in addition to the nonopiate. Finally, continued treatment for worsening pain includes the addition of a strong opioid to replace the weak opiate, the third tier (Fig. 96.1).

Five simple principles are recommended to make the pharmacologic treatments effective: (a) oral administration of analgesics should be used whenever possible; (b) analgesics should be given at regular intervals; (c) analgesics should be prescribed according to pain intensity as evaluated with a pain scale; (d) dosing of analgesics should be adapted to the individual; and (e) analgesics should be prescribed with a constant concern for detail.14

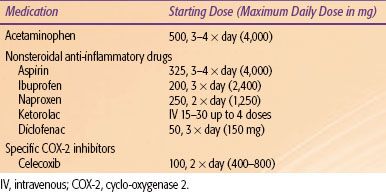

Physicians using the WHO guidelines may find it difficult to select among opioids or other medications to start with and to determine dosages to use when changing medications (Table 96.2). Often a patient may not respond to a weak opioid but may respond well to a strong opioid. When pain control becomes inadequate, the physician can climb a higher tier for guidance for better pain control.14 In light of advances in pharmacogenomics, it is increasingly clear that genetics plays a role in each individual’s sensitivity to an analgesic.15,16 If a patient does not respond or develops tolerance to a particular agent, the current medical regimen should be increased to the maximum tolerated dose or the patient rotated to a different agent.

Over time, adaptations of the WHO ladder have been proposed. In refractory pain or crises of chronic pain, a fourth step may be considered, which includes invasive techniques such as nerve blocks, neurolysis, or surgical or other interventions.9,17 Adjuvant medications including steroids, anxiolytics, antidepressants, hypnotics, anticonvulsants, antiepileptic-like gabapentinoids (gabapentin and pregabalin), membrane stabilizers, sodium channel blockers, N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonists, and cannabinoids may be used in the treatment of neuropathic pain.18,19

TABLE 96.2 GUIDE TO COMMON WEAK AND STRONG OPIOID MEDICATIONS AND POTENTIAL STARTING DOSESA

APS and NCCN Guidelines

As the understanding of pain physiology and treatments expands, so does the management strategy. Although the WHO guidelines are a good initial step in pain management, other organizations have modified and expanded these strategies to improve treatment for cancer pain. These guides provide initial medication dosages, the addition of adjuvant medications, and information on appropriate dose increases, allowing the radiation oncologist to further develop pain management skills.

The 2005 APS Guideline for the Management of Cancer Pain in Adults and Children contains detailed discussions of cancer pain management algorithms, pharmacologic strategies, coanalgesics, psychological strategies, supportive therapy, integration of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic treatments, physical strategies, nerve blocks, surgical strategies, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, and pain management in special populations. It also discusses patient education and the importance of patients’ adherence to the pain management plan, as well as how to improve quality of care in pain management.4

The latest (2010) NCCN guidelines for adult cancer pain contain the following required components: (a) pain intensity must be quantified by the patient (whenever possible); (b) a formal comprehensive pain assessment must be performed; (c) reassessment of pain intensity must be performed at specified intervals to ensure that the therapy selected is having the desired effect; (d) psychosocial support must be available; and (e) specific educational material must be provided to the patient. The guidelines also acknowledge the range of complex decisions faced in caring for these patients. They provide specific suggestions for dosing of NSAIDs, opioids, and coanalgesics; titrating and rotating of opioids; escalation of opioid dosage; management of opioid adverse effects; and when and how to proceed to other techniques/interventions for the management of cancer pain.20

Universal screening of pain should take place for cancer patients, followed by comprehensive assessment of the characteristics, underlying pathophysiology and etiology, psychosocial issues, and risk factors for undertreatment of pain. Patients’ goals and expectations should be sought for any patient whose pain score is not zero (on a visual analog or a numerical rating scale). Patients are then stratified based on the urgency and severity of the pain and treated with escalating aggressiveness. Repeat reassessments are done frequently to adjust treatment plans until patients’ goals and expectations in comfort and function are met. It is preferable to convert short-acting opioids to long-acting ones when the dose required to provide adequate pain control is determined. Rescue dosing with short-acting agents should be provided for breakthrough pain during maintenance therapy.

Opiate Side Effects

Patients taking opioids also should be provided with a bowel regimen. Side effects may limit the maximal tolerable dose of opioid analgesics. Treating a patient’s pain is a balance of maximizing analgesic effects and minimizing side effects.21 Common opioid side effects include gastrointestinal (constipation, nausea, and emesis), respiratory (decreased respiratory rate), dermatologic (pruritus and dry mouth), and central nervous system (sedation, hallucinations, and seizures) effects. Many strategies are implemented in balancing analgesic effects and side effects.22,23 Although no consensus exists, physicians can manage side effects with the following strategies:

1. Pharmacologic treatment of the side effects (e.g., high water intake, dietary fiber, stool softeners, laxatives, or the peripherally acting opioid antagonist methylnaltrexone for constipation);

2. Reduction of opiate dose;

3. Addition of adjuvant medications for pain management (see following discussion), and opioid rotation.

Opioid rotation refers to drug-switching within a group, for example, changing hydrocodone to codeine because of nausea.24 Medications should be changed every 2 to 3 months so that the patient does not become tolerant to an agent.

Adjuvant Therapy

Using the WHO ladder, pain related to cancer can be managed with oral medications in 70% to 85% of patients.11,25 At any point on the WHO analgesic ladder, adjuvant therapy can be initiated to supplement NSAIDs and opioid treatment. Benefits of adjuvant therapy include use of medications tailored to specific causes of nociceptive responses (i.e., neuropathic pain) and reduction of opiate side effects.

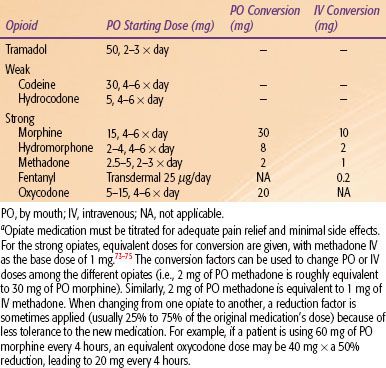

Because neuropathic pain generally is not responsive to opioid medications unless high doses are applied, other classes of medications often are prescribed.26 Anticonvulsants, such as gabapentin, carbamazepine, and pregabalin, are effective in managing neuropathic symptoms.7 Both gabapentin and pregabalin are renally excreted and have minimal drug–drug interactions, which renders these medications effective first-line treatments for neuropathic pain.7

Like anticonvulsants, antidepressants are a broad category of medications that stabilize neurons involved in neuropathic pain. Tricyclic antidepressants in low doses, such as amitriptyline, have been well studied for pain relief.27 Serotonin reuptake inhibitors and newer classes of antidepressants, including selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (milnacipran, duloxetine, and venlafaxine), are less well studied but often prescribed for neuropathic pain. Because many patients with neuropathic pain experience depression or anxiety, antidepressants may play a dual treatment role, resulting in improved efficacy in pain control.27

When faced with a patient with neuropathic pain, the radiation oncologist may prescribe an anticonvulsant, such as gabapentin, at low doses and titrate the medication to improve analgesia while monitoring side effects. Some physicians may initiate antidepressant treatment, especially if patients also exhibit signs of depression or anxiety, and then add the anticonvulsant as a secondary medication. In any case, both medications can be used synergistically to improve analgesia for neuropathic pain.

The NMDA (N-methyl-D-aspartate) receptor has received much attention for its role in modulating pain signals throughout the nervous system. Methadone is a long-acting opioid receptor antagonist, which may act also as an NMDA receptor antagonist, preventing morphine tolerance and NMDA hyperalgesia effects.28 Pain management specialists have also used ketamine, a specific NMDA receptor antagonist, to relieve cancer and neuropathic pain, especially refractory pain.29

Other adjuvant analgesic drug classes used in cancer therapy include local anesthetics, steroids, muscle relaxants, benzodiazepines, α-adrenergic agonists, and bisphosphonates.29 In recent years there has been a resurgence in clinical trials of cannabis extracts and analogs in the treatment of refractory cancer pain.30 Many of these medications are used in specific pain syndromes, which may be useful for the radiation oncologist (Table 96.3).

Nonoral Routes of Administration

Chemotherapy, surgery, and radiotherapy often produce significant side effects. Pain medications given by mouth may not be the most appropriate mode of delivery. When changing from oral to another delivery mode, care must be taken to give equipotent analgesic doses. Conversion charts for opioids are readily available in the literature.22

Some pain medications come in formulations that can be delivered rectally, intramuscularly, intravenously, or topically. NSAIDs and opioids are commercially available in suppository form. Intramuscular delivery of morphine and other medications shows variable efficacy and is not recommended.31 Patient-controlled analgesia allows patients to regularly administer intravenous medications without nursing assistance, especially in the inpatient setting. Both fentanyl and lidocaine are available in a transdermal patch.32 Capsaicin cream and a newer transdermal patch are effective for the local treatment of neuropathic pain.33,34

TABLE 96.3 COMMON ADJUVANT MEDICATIONS WITH STARTING DOSAGES AND COMMON SIDE EFFECTS