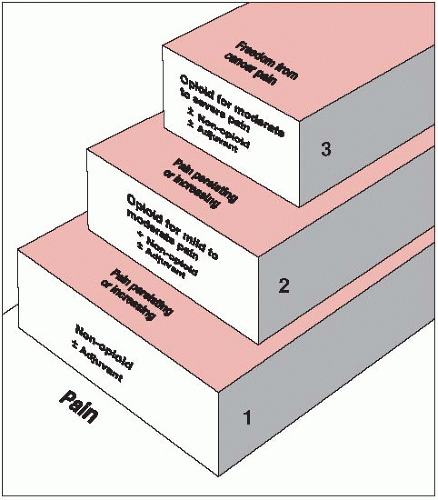

Pain control in patients with cancer is a significant issue in radiation oncology practice. Though opioids form the mainstay of analgesics in the treatment of moderate-to-severe pain, other coanalgesics such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, anticonvulsants, and opioids are frequently used, depending on the severity of pain (Fig. 52-1).

Antineoplastic therapy is the best treatment for cancer pain; however, comprehensive cancer pain management should include both treatment of disease and administration of analgesics that effectively control pain.

Anesthetic and neurosurgical approaches to pain management, including nerve blocks, epidural or intrathecal catheter placement, and electronic devices, should be considered in patients with intractable pain.

Optimal management of cancer pain requires a clear history detailing factors related to the pain, a thorough physical and neurologic examination, and diagnostic studies targeted to determine its etiology.

The history should also include evaluation of the response to analgesics, including time to onset of peak effect, duration of action, and side effects.

Objective parameters of acute pain are often absent.

Diagnostic studies should be performed to help direct therapeutic intervention because pain frequently is the first indicator of disease progression (8).

Cancer pain can be divided into somatic/visceral pain and neuropathic pain; these two types differ in etiology, symptoms, and response to analgesics and palliative irradiation (11, 14).

Somatic or visceral pain arises from direct stimulation of afferent nerves due to tumor infiltration of skin, soft tissue, or viscera.

Visceral pain tends to be poorly localized and is often referred to a dermatome remote from the source of pain.

Common causes of somatic pain include bone metastases, liver metastases that result in capsular distention, biliary, bowel, or ureteral obstruction, and distention of normal skin or soft tissue structures from an expanding tumor mass.

Neuropathic pain develops after injury to or chronic compression of peripheral nerves. Common causes of neuropathic pain include tumor invasion of a nerve plexus, spinal nerve root compression, herpes zoster infection, or surgical interruption of intercostal nerves (thoracotomy or mastectomy) (23).

Neuropathic pain is described as sharp, burning, or shooting and is often associated with paresthesias and dysesthesias. Response to conventional analgesics is usually poor, but antidepressant or anticonvulsant medications may be helpful.

Radiation therapy is one of the most effective therapeutic options (and often the only one) to relieve pain caused by bone metastases, nerve compression, or infiltration by a malignant tumor.

FIGURE 52-1 World Health Organization three-step analgesic ladder. (From World Health Organization. Cancer pain relief, 2nd ed. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 1996, with permission.)

In patients with a reasonable survival expectation, neuropathic pain can often be best relieved by high-dose, extended-course irradiation, taking into account the tolerance of the spinal cord and brachial plexus.

Pharmacologic principles for cancer pain management include an understanding of the metabolism, duration of action, and mechanism of action for nonopioid and opioid analgesics and coanalgesics.

Nonopioid analgesics, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, are generally used for mild pain or to complement opioid analgesics in treating severe pain.

Opioid analgesics, which include codeine phosphate, oxycodone hydrochloride, and morphine sulfate, are used to treat moderate to severe pain.

Coanalgesics such as amitriptyline hydrochloride and corticosteroids act as an adjuvant to opioid analgesics (12, 18, 20).

Dose schedules for various pain control agents are summarized in Table 52-1.

The choice of an analgesic drug must be individualized. Too often, this choice is influenced by unfounded fears of the patient and physician about tolerance, addiction, and respiratory depression, rather than the level of pain experienced.

TABLE 52-1 Classes of Agents Used in Cancer Pain Control

Commonly Used Drugs

Usual Doses (Adults)

Group I: Non-Narcotic Analgesics (Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs)

Acetylsalicylic acid

650 mg q4h p.o.

Acetaminophen

650 mg q4h p.o.

Naproxen

250-275 mg q6-8h p.o.

Ibuprofen

400-600 mg q6h p.o.

Ketoprofen

25-60 mg q6-8h p.o.

Ketorolac

10 mg q4-6h to a maximum of 40 mg/day

Group II: Narcotic Agonist and Antagonist Drugs

Narcotic agonists

Morphine and cogeners

Morphine

30 mg q3-4ha

Controlled-release morphine

30-120 mg ql2ha

Hydromorphone

7.5 mg q3-4ha

Codeine

180-200 mg q3-4ha

Oxycodone

30 mg q3-4ha

Hydrocodone

30 mg q3-4ha

Levorphanol

4 mg q6-8ha

Meperidine and cogeners

Meperidine (Demerol)

Not recommended

Methadone and cogeners

Propoxyphene (Darvon)

Not recommended

Methadone (Dolophine)

20mgq6-8h

Transdermal fentanyl (Duragesic)

25-100 µg/h q3d

Partial agonists and agonist-antagonist drugs

Pentazocine

Not recommended for chronic dosing in cancer patients

Buprenorphine

Not recommended for chronic dosing in cancer patients

Nalbuphine

Not recommended for chronic dosing in cancer patients

Butorphanol

Not recommended for chronic dosing in cancer patients

Group III: Adjuvant Analgesic Drugs

Anticonvulsants

Phenytoin

300-500 mg q.d. p.o.

Carbamazepine

200-1,600 mg q.d. p.o.

Methotrimeprazine

40-80 mg q.d. i.m. in divided doses

Tricyclic antidepressants

Amitriptyline

25-150 mg/day p.o.

Doxepin

25-150 mg/day p.o.

Imipramine

20-100 mg/day p.o.

Trazodone

75-225 mg/day p.o.

Steroids

Dexamethasone

16-96 mg q.d. p.o.

Prednisone

40-80 mg q.d. p.o.

Group III: Adjuvant Analgesic Drugs

Antihistamine

Hydroxyzine

300-450 mg q.d. i.m.

Stimulants (including amphetamines)

Dextroamphetamine

5-10 mg q.d. p.o.

Methylphenidate

5-15 mg q.d. p.o.

Mexiletine

450-600 mg q.d. p.o.

a Usual oral starting dose.

Source: Modified from Jacox A, Carr DB, Payne R. New clinical practice guidelines for the management of pain in patients with cancer. N Engl J Med 1994;330:651-655.

There is essentially no risk of addiction.

With long-term use of analgesics, there is no apparent effect on intellectual function, no definable deterioration in personality, and no metabolic derangements.

The most common side effects of analgesics are constipation and nausea, which should be anticipated and treated prophylactically.

Opioid-related nausea can be treated by either using an alternative narcotic analgesic or administering an antiemetic such as prochlorperazine (Compazine), metoclopramide (Reglan), haloperidol (Haldol), or ondansetron (Zofran) in combination with the analgesic (5).

Constipation can be prevented with cathartics and stool softeners (e.g., Senokot S, Colace, Peri-Colace, Dulcolax). Occasionally, an osmotic agent, such as lactulose, is necessary.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree