Abstract

Pain is a common occurrence in cancer patients, with a prevalence of approximately 39%, even in patients who have undergone curative treatment. The pain can last for years or even decades after diagnosis and treatment. This pain is usually multifactorial in nature and can result from direct tumor invasion, side effects from chemotherapy, as well as sequelae of diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. Pain can be classified as being nociceptive, neuropathic, myofascial, thalamic, and funicular. Specific syndromes such as malignant spinal cord compression, meningeal carcinomatosis, chronic regional pain syndrome, and acute or chronic radiation–induced sequelae are just a few of the common issues to consider. Gathering a comprehensive history is important in this frequently complex patient population and should include screening for depression, maladaptive behavior, and functional level. Appropriate diagnostic testing and broad differential diagnoses are critical to achieve optimal outcomes. Treatment for cancer-specific pain syndromes can be multifaceted and should involve a multimodal approach, including rehabilitation, complementary and alternative medicine, pharmaceutical treatment, and interventional techniques when appropriate.

Keywords

Cancer-related pain, Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy, Malignant spinal cord compression, Meningeal carcinomatosis, Radiation-induced pain

Introduction/Epidemiology

Pain is one of the most common symptoms related to cancer and overall cancer treatment, and cancers of the brain and spinal cord are no exception. In fact, pain is frequently the initial presenting symptom for these types of cancers. Pain prevalence rates are about 39% after curative treatment and up to 66%–80% in advanced, metastatic, or terminal cancers. Moderate to severe pain (numerical rating scale score ≥5) was reported by 38.0% of all patients. Cancer-related pain, in general, is caused by either direct tumor involvement, diagnostic or therapeutic procedures, and the side effects or toxicities of treatment. Of course, individual patients may have more than one type of cancer-related pain at the same time. Painful procedures include surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, and supportive or diagnostic procedures. The different types of pain, the approach to the assessment of pain in brain and spinal cord malignancies, and the various available treatments will be discussed in this chapter.

Etiology

Types of Pain

Nociceptive

Nociceptive pain is typically what people think of when they think of pain. This is the type of pain everyone is familiar with. It is defined as pain that is triggered by the activation of the peripheral receptive terminals of the primary afferent neurons. These nociceptors fire in response to noxious irritants such as chemical, mechanical, or thermal stimuli. Unlike the other types of pain discussed in the following sections, nociceptive pain is unique in that the pain is proportional to the nociceptive input.

Neuropathic

Neuropathic pain in cancer is very common, occurring in between 19% and 21% of all cancer patients who report having pain and in up to 90% of patients receiving neurotoxic chemotherapies. Neuropathic pain can have a substantial impact on quality of life of a cancer patient as it can impact activities of daily living (ADLs), ambulation, fine motor tasks, mood, and sleep. It can be challenging to manage as it is commonly just one layer in the complex pain syndromes of patients. However, neuropathic pain is a distinct entity unto its own and must be addressed as such.

Clinical characteristics unique to neuropathic pain include sensory abnormalities such as thermal and cold allodynia, paresthesias, mechanical hyperalgesia, and dysesthesias. Pain is described as “burning”, “stabbing”, “numb”, or “pins and needles.” Severe cases can affect the motor nerves as well, resulting in weakness. In the setting of cancer, the most common type is a painful peripheral neuropathy resulting from specific types of chemotherapies. Referred to as chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN), it is most often a dose-dependent, cumulative adverse effect of treatment with certain drugs. It usually is also length-dependent, resulting in a stocking-and-glove distribution of pain and impairment.

For example, one of the most commonly used combination chemotherapy regimens in neuro-oncology is procarbazine, lomustine, and vincristine (PCV). Of these, vincristine is known to result in a polyneuropathy characterized by numbness and tingling and/or burning of the hands and feet. The drug exerts its antitumor effects by disrupting microtubule structures required for mitosis and cell division. Unfortunately, these same structures are also implicated in axonal transport of nutrients, and thus we see a “dying back” effect in the damaged nerves. Vincristine can affect any nerve and so results in a mixed sensorimotor neuropathy with possible autonomic involvement.

In another example, spinal cord gliomas are commonly treated with cisplatin and carboplatin, both members of the group of platinum chemotherapies. These compounds exert their damaging effects in the dorsal root ganglia, resulting in a pure sensory neuropathy. Patients receiving this chemotherapy, unlike PCV, would not have any muscle weakness—an important clinical distinction. They can, however, have paresthesias of the hands and feet, loss of deep tendon reflexes, and impaired vibration and proprioception. A unique feature of the platinum compounds is that the symptoms can continue to worsen, and even peak, weeks or months after the last dose has been administered. This phenomenon is known as “coasting.” As you might imagine, this can result in undue anxiety on the part of the patient and the uninformed clinician.

Myofascial

Myofascial pain is pain that arises from myofascial trigger points, which are small localized areas of taut muscle bands that are sometimes palpable. They are hypersensitive and tender to palpation, frequently reproducing a patient’s pain, including any referral patterns. They frequently occur after a discrete trauma or injury but can be insidious in onset as well. In CNS cancer patients who have developed new patterns of movement, a high clinical suspicion for this type of pain should be maintained as it frequently follows postural abnormalities. The pain is regional in nature and described as a deep ache. There are many treatment options, the mainstays of which are exercise, stretching, postural/ergonomic considerations, and trigger point injections.

Thalamic

Thalamic pain is a type of central pain syndrome that can be severe and difficult to treat. It typically occurs in those who sustain damage to the ventrocaudal regions of the thalamus, although it occurs from other damaged thalamic nuclei and it is difficult to predict which patients will develop it and which will not. It is generally seen in patients who have suffered a thalamic stroke and considered a type of central poststroke pain. However, cancerous lesions and subsequent cancer treatments affecting the thalamus may also result in this pain syndrome. It is characterized by severe and paroxysmal pain producing a sensation described as burning. It is activated by cutaneous stimulation and changes in temperature and can be accompanied by hyperalgesia and allodynia.

Funicular

Funicular pain is another type of central pain disorder that is the consequence of a lesion or disease of the ascending spinothalamic tracts. This can occur secondary to radiation to spinal lesions, for example, or secondary to mass effect resulting in compression of the tract. The result of this ectopic activity in this tract is a nebulous type of excruciating pain that can be difficult to diagnose. It does not follow in any fixed dermatomal pattern and pain can be experienced anywhere in the body caudal to the lesion.

Specific Syndromes

Malignant Spinal Cord Compression

Spinal cord or cauda equina compression as a result of mass effect is present in approximately 3%–14% of all cancer patients and is referred to as malignant spinal cord compression. After brain metastasis it is the second most common neurologic complication of cancer. It can have a major impact on a patient’s quality of life—frequently resulting in not only pain but also paralysis and incontinence. Most patients who are affected by it are those with advanced cancers with limited survival. It is often considered a medical and surgical emergency.

The spine itself is the most frequent site of osseous metastases, occurring in about 40% of patients. Over half of the cases result from cancers of the breast, prostate, and lung. Other common associated cancers are lymphoma, renal cell carcinoma, multiple myeloma, melanoma, and head and neck cancers, including thyroid cancer.

Pain is usually secondary to mass effect of a metastasis distorting the anatomy of the pedicle or vertebral body itself. This can occur independent of vertebral body collapse, which, of course, may further distort the anatomy and have its own impact on surrounding structures. Epidural compression is by far the most common cause. Either the mass grows into the epidural space and compresses the spinal cord, into the neuroforaminal space, or the metastasis results in vertebral body collapse displacing bone fragments into the epidural space. Most malignant spinal cord compression occurs in the thoracic vertebra (70%), followed by the lumbar spine (20%), and then the cervical spine (10%). About one-fifth of cases will have multiple instances of compression.

The vast majority of cases of malignant spinal cord compression initially present with pain (>90%). But motor weakness (76%–78%), autonomic dysfunction (40%–64%), and sensory loss (51%–80%) are also common. Pain may be acute or long-standing at the time of diagnosis. The nature of this pain is variable, largely dependent on the site of compression. Pain localized to just one area is not always the case, although local tenderness is common. Spinal percussion may reproduce this local pain. Compression of the exiting nerve roots generally results in a unilateral radicular pain in the cervical and lumbar spine but is more frequently bilateral in thoracic compression. This is because the spaces available are narrower in the thoracic spine. In general, there are some associated pain syndromes caused by vertebral metastases. These are outlined in the table below :

| Location | Bone Pain | Radicular Pain | Other Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cervical spine | “Constant, aching” pain in the paraspinal area radiating to both shoulders | Unilateral radiating to the shoulder and medial aspect of the arm | Tenderness on percussion of spinous process; parestheisas and numbness in digits 4 and 5; progressive weakness of triceps and hand |

| Lumbar spine | “Aching” pain in the midback with referred pain to unilateral or bilateral sacroiliac joints | Pain in groin/thighs | Exacerbated by sitting or lying down, relieved by standing or vice versa |

| Sacral spine | “Aching” pain in sacral and/or coccygeal region | n/a | Perianal sensory loss; bowel and bladder dysfunction/incontinence; impotence; exacerbated by sitting and relieved with ambulation |

| Epidural spinal cord compression | “Aching” pain and tenderness in the affected vertebrae; stocking distribution of leg pain | May or may not be present | Upper motor neuron signs; motor weakness progressing to paraplegia; sensory loss; bowel and bladder dysfunction |

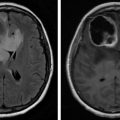

Meningeal Carcinomatosis

Meningeal Carcinomatosis (MC), also called leptomeningeal carcinomatosis or neoplastic meningitis, is a disease wherein intracranial primary tumors or extracranial malignant cells disseminate or focally invade into the meninges and spinal subarachnoid. It usually results from metastatic spread into the cerebrospinal fluid. Once there, the cancerous seedlings develop on the meninges of the brain and spinal cord and may invade the nearby CNS tissue as well.

Most patients with MC first present with headache, which may be severe, and associated symptoms and signs of meningeal irritation. These include nausea, vomiting, photophobia, and nuchal rigidity. Other presentations may include epilepsy, cervical radicular pain, hemiplegia, and unconsciousness. In a cohort of 60 patients with breast cancer leptomeningeal metastases, headache was the most common presenting symptom (55%), followed by various cranial neuropathies and epilepsy (50% and 12%, respectively). Vertigo presented in 12 patients (20%).

Complex Regional Pain Syndrome

Complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) is more likely a result of surgical or nonsurgical trauma as well as cervical spine or spinal cord disorders. Malignancy in general is an infrequent cause. The mechanism of the syndrome is unclear, but it is theorized to result from sympathetic nervous system hyperactivity and some degree of inflammatory response. CRPS is likely both a peripheral and central pain syndrome. The major pathologic change is thought to be the development of sensitivity of peripheral nociceptors to sympathetic stimulation. Patients frequently have spontaneous pain or allodynia/hyperalgesia not limited to the territory of one peripheral nerve. Skin changes, hair loss, sudomotor alterations, or edema are also a necessary part of making this diagnosis.

Radiation Therapy Pain

Radiation-induced pain

Radiation is associated with several different types of pain syndromes. Patients may experience pain from brachytherapy, wherein radioactive seeds are placed inside the body. Positioning the body during radiation treatment and even getting onto the table for treatment may be uncomfortable. Delayed tissue damage from radiation including mucositis, mucosal inflammation in areas receiving radiation, may occur. Radiodermatitis is the skin’s reaction and is frequently painful. Finally, a temporary worsening of pain in the treated area, knows as a pain flare, is a potential side effect of radiation treatment for bone metastases. Steroids, including dexamethasone, are frequently prescribed to reduce the incidence of these pain flares.

Patient Assessment: The Pain History

The proper assessment of pain in the setting of cancer is frequently underperformed, which results in a high level of unnecessary distress in patients and their families. Barriers to proper assessment include patient’s reluctance to discuss their pain, lack of time for the clinical encounter, low priority placed on pain, hesitancy on the part of clinician in prescribing opioids and other pain medications, and the infrequent use of standardized pain assessment tools, among others.

The pain experience is the end result of a very complex, multifaceted process. The traditional biomedical model assumes a solid relationship between nociceptive pain and an underlying, organic process. Sometimes this is the case, but very frequently this view is an incomplete one. A better approach to integrating all the aspects of pain in an assessment is to address some central questions to cancer patients who report pain. The first is to assess the extent of the patient’s disease or injury. This would include questions regarding nociceptive pain and the physical impairments that have resulted from their cancer or cancer treatments. The second aspect is to assess the magnitude of the illness. This would include questions regarding the extent to which the patient is suffering, disabled, and unable to enjoy their favorite activities. The third aspect is the assessment of the psychologic contribution to their pain. This is elucidated by asking about any concomitant depression or anxiety and the presence of stressful events. Studies show that at least half of all chronic pain patients suffer from depression. The last aspect of the assessment is the awareness of any pain behaviors. Pain behaviors are the way that a patient responds to pain. This can be moaning, facial grimacing, guarded movements, altered gait, etc. They also include habitual patterns such as coping behaviors and incorporate maladaptive pain behaviors, such as catastrophizing, as well.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree