CHAPTER 10 Overseas Medical Screening for Immigrants and Refugees

Introduction

Migration is a major human and global phenomenon, with many complex linkages to economic, trade, social, security, and health policies. In the dynamic relationship between migration and health, immigration has long been recognized to have a large impact on disease epidemiology and the use of health services in migrant receiving nations.1 For example, the impact of immigration on disease epidemiology is demonstrated by the global epidemiology of tuberculosis (TB). Tuberculosis is a leading global cause of infectious disease morbidity and mortality; however, rates of TB in most regions of the developing world are many times higher than those in the developed world (i.e. the TB prevalence gap), and decreasing at a much slower rate.2 Many migration receiving countries in the developed world have had stable or increased migration of persons from regions with high TB prevalence, while at the same time have successfully decreased TB incidence in their native-born population, further exacerbating this prevalence gap. Consequently, the majority of TB cases in migration receiving countries such as the US and Canada are now being diagnosed in foreign-born populations from high-prevalence source countries.3,4

Many immigration receiving countries have pre-arrival medical examination requirements and protocols for entering migrants, which vary both by the types of populations screened, and the diseases for which examination is required. As an example, the US currently does not require a sputum culture for TB diagnosis, while it is required by some other receiving countries. The health conditions tested through the medical examination procedures required by countries such as Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States of America are determined on the basis of the risk or danger that these conditions can represent to public health and safety and the additional costs that may be incurred by national public services expenditures.5–9 In general, these medical examination procedures include a review of the past medical history, a physical examination, and tests that include a chest X-ray and laboratory analyses. The diseases most frequently tested for to determine visa eligibility or the admissibility of a migrant are infectious diseases such as tuberculosis, sexually transmitted diseases, and mental or behavioral conditions. Immigration regulations in some of these countries do allow for the consideration of medical waivers to inadmissible health conditions. Although many immigration receiving countries in Europe either do not require pre-arrival health evaluations or have fewer requirements and only limited grounds for refusal of admission based on health grounds, most have provisions for notification and inspection if a communicable or serious health condition is recognized or suspected.10,11

US Migration and Health Screening Policies

The number of foreign-born persons living in the US, approximately 28 million, is greater than ever before in the nation’s history.12 In 2004, the foreign-born proportion of the total US population reached approximately 12%, a proportion comparable to the peak reached during the great immigration wave at the turn of the twentieth century. In contrast to the previous twentieth-century US immigration wave, which was dominated by Eastern Europeans who were driven from their countries of origin by factors such as persecution and poverty (so called ‘push factors’), the twenty-first-century immigration wave, which began in the 1970s, is characterized predominantly by Hispanic migrants followed by Asian migrants who are attracted to the US for economic opportunities (or ‘pull factors’). In both waves of migration, migrants have brought with them not only skills and cultural traditions that enriched US economic and social fabrics, but also diseases and disease exposures which were different from those existing in US receiving communities. In addition, twenty-first-century migrants are more mobile and remain connected to their countries of birth, typically making several back and forth journeys to visit friends and relatives (VFR). New immigrants and refugees who cross disease prevalence gaps and their frequent VFR travel patterns constitute potentially high-risk populations for translocating communicable diseases of public health significance.

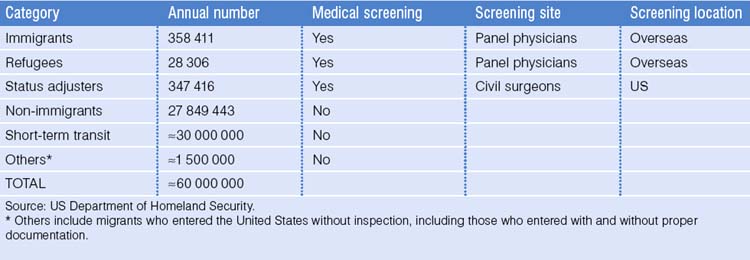

The Department of Homeland Security has reported that approximately 60 000 000 migrants enter the United States annually (Table 10.1).13 These migrants include immigrants, refugees, migrants adjusting their visa status, persons with non-immigrant visas, persons in short-term transit status, and other groups of migrants who entered the United States without inspection, including undocumented migrants. The majority of these migrants are not required to undergo medical screening prior to US entry. Given the immense numbers of persons crossing US borders and finite resources for evaluation and surveillance, US migrant health screening policy focuses on migrants planning to establish permanent US residence, as this group has the largest potential long-term impact both on disease epidemiology and healthcare resources utilization. Currently, the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) requires that medical screening examinations be performed overseas for all US-bound immigrants and refugees, and in the United States for migrants applying to adjust their visa status to permanent residence (i.e. ‘green cards’).8,9,14,15 In 2003, approximately 700 000 immigrants, refugees, and migrants seeking visa status adjustment underwent medical screening examinations. The remainder of this chapter will discuss US overseas medical screening issues for US-bound immigrants and refugees. The two following chapters will address screening programs and individual health assessments for new immigrants on arrival in the US.

Required Overseas Medical Screening Examinations for US-Bound Immigrants and Refugees

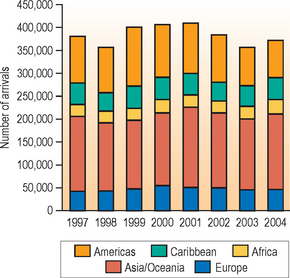

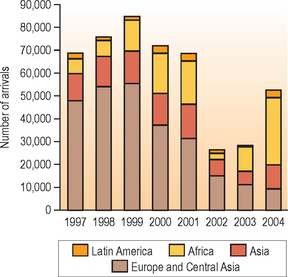

On average, approximately 400 000 documented immigrants and refugees arrive in the US annually; immigrants comprise approximately 90% of arrivals, and refugees close to 10%.13 Trends in the number and regions of origin for US-arriving immigrants and refugees are presented in Figures 10.1 and 10.2. From 1997 to 2004, over 3 million immigrants arrived in the US; the number of arrivals and regions of origin remained relatively stable over the 8 years examined. Between 357 000 and 410 000 immigrants arrived annually; 43% from Asia/Oceania, 26% from the Americas (with the majority of these arrivals [roughly 60%] from Mexico), 13% from the Caribbean, 12% from Europe, and 7% from Africa. From 1997 to 2004, close to 560 000 refugees arrived in the US; in contrast to immigrants, the number of arrivals and regions of origin have changed markedly over the 8 years examined. From 1997 to 2001, the number of refugees entering the US remained stable at approximately 70 000 per year. However, after the September 11 terrorist attacks, increased security requirements delayed some refugee processing, and therefore the number of refugees arriving in 2002 and 2003 decreased to 30 000 or less. It is reported that almost 53 000 refugees arrived in the US by the end of 2004. The number and proportions of arriving refugees from different regions of the world also changed over the 8 years examined. In 1997, the majority (70%) of arriving refugees were from Europe and Central Asia, with only 9% of arriving refugees from Africa. In contrast, in 2004, almost 55% (approximately 29 000 refugees) arrived from Africa. These trends have important implications for medical evaluation and treatment of refugees, both overseas and stateside, as refugees from Africa have relatively high rates of certain diseases, including human immunodeficiency (HIV), TB, malaria, intestinal helminth infections, and other tropical diseases (e.g. schistosomiasis), and likely lack routine vaccinations.

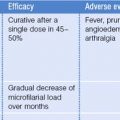

All immigrants and refugees migrating to the United States are required to have a medical screening examination overseas, which is performed by local physicians (panel physicians) appointed by the local US embassy.8,9 The mandated medical examination focuses primarily on detecting diseases determined to be inadmissible conditions for the purposes of visa eligibility. These diseases include certain serious infectious diseases such as infectious tuberculosis, human immunodeficiency virus infection, syphilis, and other sexually transmitted infections, and infectious Hansen’s disease. Other diseases (noninfectious) designated as inadmissible conditions include mental disorders associated with harmful behavior, and substance abuse. For the purposes of determining the inadmissibility of an applicant, medical conditions are categorized as class A or B. Class A conditions are defined as those conditions which preclude an immigrant or refugee from entering the US. Class A conditions require approved waivers for United States entry and immediate medical follow-up upon arrival. These conditions include communicable diseases of public health significance, a physical or mental disorder associated with violent or harmful behavior, and drug abuse or addiction. Class B conditions are defined as significant health problems: physical or mental abnormalities, diseases, or disabilities serious in degree or permanent in nature amounting to a substantial departure from normal well-being. Follow-up evaluation soon after US arrival is recommended for migrants with class B conditions. If immigrants or refugees are found to have an inadmissible condition that may make them ineligible for a visa, a visa may still be issued after the illness has been adequately treated or after a waiver of the visa eligibility has been approved by US Customs and Immigration Services.

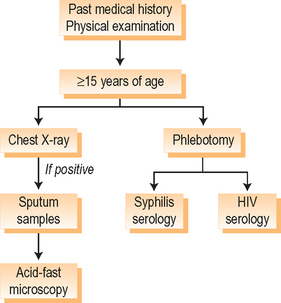

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Division of Global Migration and Quarantine (DGMQ), is responsible for providing technical guidance to the panel physicians in performing the overseas medical screening examination.14 The testing modalities recommended for the medical examination are outlined in Table 10.2, and the algorithm for the required overseas medical screening examination is presented in Figure 10.3. The CDC, DGMQ, is also responsible for monitoring the quality of the overseas medical examination process at over 650 panel physician sites (healthcare staff, radiology facilities, vaccination protocols, and laboratories) worldwide, through its Quality Assurance Program (QAP). Due to limited resources, not all panel physician sites can be visited and assessed annually. Sites are prioritized for monitoring, based upon the number of immigrant and refugee visas processed and country-specific prevalence of such diseases as tuberculosis and human immunodeficiency virus. In addition, DGMQ performs remediation visits when medical screening examination deficiencies have been identified. In an effort to share experiences regarding the optimization of immigration medical processes, technical aspects of the medical screening, the performance evaluation of panel physicians, and review policies, regulations, and practices of the various resettlement nations, DGMQ has met with sister agencies from other countries to discuss possible approaches to common challenges such as health information systems, privacy, confidentiality, and resource utilization and constraints.

Table 10.2 Testing for required overseas medical screening examination

| Health condition | Testing |

|---|---|

| Tuberculosis | Chest radiograph; AFB smear if CXR+ |

| HIV | Serology |

| Syphilis | Serology |

| Other sexually transmitted diseases | Physical examination |

| Hansen’s disease | Physical examination |

| Mental disorders with associated harmful behavior | History |

| Drug abuse or addiction | History, physical exam |

| Vaccinations | History, vaccination records, serology |

Source: CDC, DGMQ.

The CDC, DGMQ, is also responsible for notifying state and local health departments of all arriving refugees and those immigrants with class A or B health conditions who are resettling in their jurisdiction and need follow-up evaluation and possible treatment in the US.8,9 Under the current system, US Department of State forms summarizing the results of the overseas medical examination, including classification of health conditions, are manually collected at US ports of entry. This information is transmitted to state and local health departments through the US mail. State and local health departments are asked to report to DGMQ the results of these US follow-up evaluations, and any significant public health conditions occurring among recently arrived immigrants and refugees, as a way to better understand epidemiological patterns of disease in recently arrived migrants and to monitor the quality of overseas medical examination. Public health models for accomplishing these goals are discussed in Chapter 11.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree