According to the American Cancer Society statistics, there are 21,880 estimated new cases of ovarian cancer in the United States, with an estimated death toll of 13,850 (2).

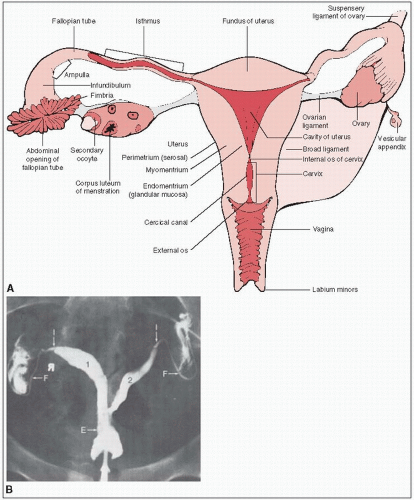

The paired ovaries are light gray and approximately the size and configuration of large almonds (Fig. 37-1).

During the reproductive years, the ovary weighs 3 to 6 g and measures approximately 1.5 × 2.5 × 4.0 cm.

The mesovarium, ovarian ligament, and infundibular pelvic (suspensory ligament of the ovary) ligaments determine the anatomic mobility of the ovary.

The mesovarium ligament contains the arterial anastomotic branches of the ovarian and uterine arteries.

The ovarian ligament is a narrow, short, fibrous band that extends over the lower pole of the ovary to the uterus. The suspensory ligament attaches the ovary to the lateral pelvic walls and contains the ovarian artery, veins, and accompanying nerves.

Lymphatic drainage is primarily to the periaortic nodes at the level of the renal veins. The external iliac and inguinal lymph nodes may be involved by retrograde lymphatic flow.

Carcinoma of the ovary is a disease of older women, with a peak incidence in the fifth to seventh decade. It is rarely seen before menarche, but when it is seen, ovarian germ cell tumors predominate.

Endocrine effects of carcinogenesis may be related to the number of uninterrupted ovulatory cycles. Nulliparous women are at an increased risk of ovarian cancer compared with those who have borne children; multiple pregnancies exert an increasingly protective effect.

Oral contraceptives have a protective effect, particularly in nulliparous women.

Hereditary site-specific ovarian cancer syndrome, hereditary breast/ovarian cancer syndrome, and Lynch II cancer family syndrome occur as autosomal-dominant traits with a variable penetrance. The last is characterized by nonpolyposis colorectal cancer, endometrial cancer, and ovarian cancer.

Peutz-Jeghers’ syndrome is associated with an increased risk of sex cord-stromal tumors.

Sunlight, which is related to vitamin D synthesis for ovarian cancers, has been reported as a protective factor; low incidences of this type of cancer are found in countries with high amounts of sunlight.

Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate and short-term use of tamoxifen have not conclusively been shown to be associated with an increased risk of ovarian cancer.

Family history of BRCA1 or BRCA2 increases the risk of ovarian cancer.

Epithelial ovarian carcinoma arises from the ovarian surface epithelium.

Early disease is confined to the ovary as a cystic growth.

Dissemination occurs through transcoelomic, lymphatic, or hematogenous spread.

All peritoneal surfaces are at risk for tumor implantation and nodule growth. The peritoneal surfaces of the diaphragm, liver, and spleen are frequently coated by tumor.

The most frequently associated nodes are the periaortic and pelvic lymph nodes, which are involved in approximately 10% to 25% of patients with clinically localized disease and up to 80% of those with advanced disease.

Autopsy findings have revealed involvement of pelvic nodes in 80% of all cases, periaortic nodes in 78%, inguinal nodes in 40%, mediastinal nodes in 50%, and supraclavicular nodes in 48% (5).

Hematogenous metastases occur to the liver, lung, pleura, and, less frequently, to the bone, kidney, bladder, skin, adrenal gland, and spleen.

Common genetic abnormalities are c-myc, H-ras, K-ras, and the neu oncogenes.

Latzko’s triad (11% to 15%) is pelvic pain, pelvic mass, and serosanguinous vaginal discharge.

Hydrops tubae profluens (rare) is colicky lower abdominal pain alleviated with release of sporadic, yellowish watery vaginal discharge.

Because early gastrointestinal symptoms are nonspecific, women present with early-stage disease only 15% to 25% of the time.

Detection of early-stage disease usually occurs by palpation of an asymptomatic adnexal mass on routine examination.

Most adnexal masses are not malignant, and in premenopausal women, ovarian cancer represents fewer than 5% of adnexal neoplasms.

An adnexal mass in a postmenopausal woman has a higher likelihood of malignancy, and surgical exploration is usually indicated.

Most women are diagnosed after the disease has spread beyond the pelvis and presents as abdominal pain or discomfort with increased abdominal girth related to ascites or large intraabdominal masses.

The diagnostic workup and preoperative evaluation of a patient suspected of having ovarian malignancy should include an initial full history and physical assessment, including bimanual pelvic examination.

Transvaginal ultrasonography is more sensitive in the assessment of adnexal masses, especially when combined with color flow Doppler.

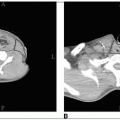

Computed tomography (CT) is useful in the detection of upper abdominal and retroperitoneal disease.

Routine laboratory studies should include a complete blood cell count, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, liver enzymes, and CA 125 level. Other tumor markers have been investigated to enhance the specificity of CA 125.

CA 19-9, along with carcinoembryonic antigen, is useful in monitoring patients with mucinous subtypes of ovarian cancer.

Human chorionic gonadotropin (beta-hcG) and alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) are the most useful markers for germ cell tumors.

Patients also should undergo routine preoperative surgical clearance.

The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics staging classification is the most widely used classification system (Table 37-1).

Ovarian carcinoma staging requires a thorough surgical exploration. The surgeon should be able to perform the procedures listed in Table 37-2, as outlined by the Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG).

After appropriate staging procedures have been completed, a total abdominal hysterectomy should be performed with a bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and appendectomy. The appendectomy is necessary because of a high frequency of metastatic involvement.

Patients who did not undergo complete surgical staging at the time of the initial surgical procedure should have a second-look laparotomy.

CA 125 is the best available tumor marker for ovarian carcinoma. It detects up to 89% of patients with serous adenocarcinoma of the ovary, compared with only 68% of those with mucinous tumors, which are better detected with CA 19-9 (18).

The upper limit for a normal serum level of CA 125 is 35 units per mL. Levels above this are suspicious for ovarian malignancy; however, this level is insufficiently sensitive to be used as a screening tool for ovarian cancer.

CA 125 can accurately reflect tumor burden after surgery and cytotoxicity. In one study, if CA 125 levels decreased less than 60%, the sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive value for residual disease larger than 2 cm was 100% (6).

CA 125 levels should be interpreted with caution until 3 to 4 weeks after surgery because the surgery itself may reflect increases in CA 125 as a result of peritoneal inflammation.

Probably the most valuable and reliable use of CA 125 is for detection of disease recurrence and progression. When monthly CA 125 levels and clinical examination were evaluated, progressive disease could be diagnosed in 92% of patients (22).

The World Health Organization and International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics adopted a unified classification of the common epithelial, germ cell, sex cord, and stromal tumors.

Of all malignant ovarian tumors, 85% to 90% are epithelial, arising from the germinal epithelium of the ovarian surface. Serous cystadenocarcinoma is the most common of these, accounting for 42%.

Fewer than 10% of all ovarian malignancies are primary germ cell, sex cord, or stromal tumors.

Serous tumors are usually cystic and may be bilateral in up to 30% of patients; mucinous tumors are bilateral in only 5% to 10% of patients.

Tumor stage, volume of postoperative residual disease, and tumor grade are the major independent prognosticators for epithelial ovarian cancers.

Histologic subtypes of malignant epithelial ovarian neoplasms are of limited prognostic significance.

TABLE 37-1 Staging Systems for Carcinoma of the Ovary and Fallopian Tubes

TNM

FIGO

Definition

Primary Tumor (T)

TX

—

Primary tumor cannot be assessed

T0

—

No evidence of primary tumor

Ovary

T1

I

Tumor limited to ovaries (one or both)

T1a

IA

Tumor limited to one ovary; capsule intact, no tumor on ovarian surface. No malignant cells in ascites or peritoneal washings

T1b

IB

Tumor limited to both ovaries; capsules intact, no tumor on ovarian surface. No malignant cells in ascites or peritoneal washings

T1c

IC

Tumor limited to one or both ovaries with any of the following: capsule ruptured, tumor on ovarian surface, malignant cells in ascites or peritoneal washings

T2

II

Tumor involves one or both ovaries with pelvic extension and/or implants

T2a

IIA

Extension and/or implants on uterus and/or tube(s). No malignant cells in ascites or peritoneal washings

T2b

IIB

Extension to and/or implants on other pelvic tissues. No malignant cells in ascites or peritoneal washings

T2c

IIC

Pelvic extension and/or implants (T2a or T2b) with malignant cells in ascites or peritoneal washings

T3

II

Tumor involves one or both ovaries with microscopically confirmed peritoneal metastasis outside the pelvis

T3a

IIIA

Microscopic peritoneal metastasis beyond pelvis (no macroscopic tumor)

T3b

IIIB

Macroscopic peritoneal metastasis beyond pelvis 2 cm or less in greatest dimension

T3c

IIIC

Peritoneal metastasis beyond pelvis more than 2 cm in greatest dimension and/or regional lymph node metastasis

Fallopian Tubes

Tis

a

Carcinoma in situ (limited to tubal mucosa)

T1

I

Tumor limited to the fallopian tube(s)

T1a

IA

Tumor limited to one tube, without penetrating the serosal surface; no ascites

T1b

IB

Tumor limited to both tubes, without penetrating the serosal surface; no ascites

T1c

IC

Tumor limited to one or both tubes with extension onto or through the tubal serosa, or with malignant cells in ascites or peritoneal washings

T2

II

Tumor involves one or both fallopian tubes with pelvic extension

T2a

IIA

Extension and/or metastasis to the uterus and/or ovaries

T2b

IIB

Extension to other pelvic structures

T2c

IIC

Pelvic extension with malignant cells in ascites or peritoneal washings

T3

III

Tumor involves one or both fallopian tubes, with peritoneal implants outside the pelvis

T3a

IIIA

Microscopic peritoneal metastasis outside the pelvis

T3b

IIIB

Macroscopic peritoneal metastasis outside the pelvis 2 cm or less in greatest dimension

T3c

IIIC

Peritoneal metastasis outside the pelvis and more than 2 cm in diameter

Regional Lymph Nodes (N)—Ovary and Fallopian Tubes

NX

Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed

N0

No regional lymph node metastasis

N1

IIIC

Regional lymph node metastasis

Distant Metastasis (M)—Ovary and Fallopian Tubes

M0

No distant metastasis (no pathologic M0; use clinical M to complete stage group)

M1

IV

Distant metastasis (excludes metastasis within the peritoneal cavity)

Notes:

For both Ovary and Fallopian Tube: Liver capsule metastasis T3/stage III; liver parenchymal metastasis M1/stage IV. Pleural effusion must have positive cytology for M1/stage IV.

aFIGO no longer includes stage 0 (Tis).

Source: Staging from Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al., eds. AJCC cancer staging manual, 7th ed. New York, NY: Springer Verlag, 2009, with permission.

Overall, 5-year survival rates for stage I, II, III, and IV disease are 90%, 80%, 15% to 20%, and less than 5%, respectively (1).

Histologic grade is a particularly important prognosticator for early-stage disease. Stage I patients with grade 1,2, and 3 disease have survival rates of 97%, 78%, and 62%, respectively (7).

Figure 37-2 shows the classification of patients into three distinct risk groups based on stage, postoperative residual tumor volume, and grade. The low-risk group requires no adjuvant therapy and has excellent survival, with surgery being the only treatment modality. The intermediate-risk group constitutes almost 33% of patients with ovarian cancer; abdominopelvic irradiation is the most appropriate treatment. This group primarily includes patients with stage I and II disease, but patients with stage III disease, grade 1 optimally debulked (less than 2 cm residuum) with residual disease located in the pelvis are amenable to abdominopelvic irradiation.

In early-stage disease, other factors have been identified as independent prognosticators. Dembo et al. (11) demonstrated in 642 patients with stage I disease that tumor variables predictive for high probability of relapse after complete tumor removal are degree of differentiation, presence of dense adhesions between tumor and pelvic organs, and presence of ascites. When these factors were accounted for, no other significant prognosticators, including bilateral tumor, capsular penetration, tumor size, cyst rupture, patient age, histologic subtype, or type of postoperative therapy, were found to be significant.

Other studies have found tumor ploidy to be a significant prognosticator. Aneuploid tumors are more aggressive than diploid tumors and are generally of higher stage at presentation; they also have a shorter median survival time (4.5 versus 22.0 months, respectively) (12).

TABLE 37-2 Staging Surgical Procedures for Ovarian Cancer | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree