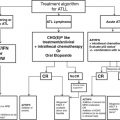

Fig. 1

Algorithm for Ovarian cancer management

6.1 Surgical Management

In advanced ovarian cancer, the aim is to achieve optimal cytoreduction, currently defined as complete resection of all disease with zero residuum (R0), ideally by a specialized gynecologic oncologist. This has been shown to be associated with a significantly increased PFS and OS [8]. However, in areas of the world which lack or are deficient in specialized gynecology oncology surgeons, ovarian cancer surgery can also be undertaken by gynecologists with training in gynecologic oncology surgery. A maximal surgical effort, including (if required) intestinal resection, peritoneal stripping, diaphragmatic resection, removal of bulky para-aortic lymph nodes, and splenectomy, should ideally be undertaken to achieve optimal cytoreduction. In advanced stage disease, systematic retroperitoneal lymph node dissection may be undertaken if adequate intraperitoneal cytoreduction has been achieved.

Although primary cytoreductive surgery is the standard approach in patients with advanced ovarian cancer, neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by interval surgery is a valid option when optimal debulking is not feasible due to poor performance status or extensive tumor dissemination. Three randomized trials have shown that neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by interval surgery is not inferior to primary debulking surgery with respect to overall survival, while treatment-related morbidity is lesser with neoadjuvant approach [9–11]. However, there remains some controversy about the role of neoadjuvant therapy before surgical debulking if the disease is surgically resectable and whether this should be the chosen option if initial disease is debulkable. Thus, when access to expert surgical resources is scarce, neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by interval surgery is an acceptable, evidence-based, alternative in patients with advanced stage disease. The same regimen (paclitaxel-carboplatin) which is used after primary surgery is also used in the neoadjuvant approach, and surgery is usually sandwiched between the third and fourth cycles of chemotherapy.

6.2 Chemotherapy

6.2.1 Standard Intravenous Chemotherapy

The combination of paclitaxel (175 mg/m2 as a 3-h infusion) and carboplatin (dosed to area under curve of 5–7), administered every 3 weeks for a total of 6 cycles, is the standard first-line adjuvant chemotherapy regimen in advanced stage ovarian cancer. This recommendation is based on a number of studies which proved the superiority of taxane-platinum compared to the previous standard of cyclophosphamide-platinum in patients with previously untreated stage III–IV disease [12, 13]. However, there was no superiority of paclitaxel-platinum over single-agent platinum in two other randomized trials [14, 15]. The latter results have been interpreted variably, including the possibility of pharmacological antagonism between cyclophosphamide and cisplatin and considerable crossover to paclitaxel in single-agent platinum arms. The latter argument suggests that these were really sequential, platinum followed by paclitaxel, strategies rather than true single-agent ones. The current broad consensus is that paclitaxel-platinum is the standard first-line regimen in advanced ovarian cancer. However, single-agent platinum is an appropriate alternative in frail patients and when use of taxanes is not feasible. Carboplatin and cisplatin can both be used in this setting although the former is preferable.

When patients have preexisting neuropathy or are at significant risk of developing it, docetaxel-carboplatin is an acceptable alternative to paclitaxel-carboplatin [16]. For those patients who develop hypersensitivity reaction to paclitaxel, the combinations of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin with carboplatin or gemcitabine with carboplatin are considered acceptable alternatives [17, 18].

6.2.2 Dose-Dense Chemotherapy

A Japanese study compared 3-weekly paclitaxel and carboplatin with the same dose of carboplatin every 3 weeks (AUC 6) and paclitaxel administered in a weekly dose of 80 mg/m2 for 18 cycles and proved the superiority of weekly regimen in terms of both PFS (28.2 vs. 17.5 months, HR = 0.76, 95 % CI 0.62–0.91; p = 0.0037) and OS (100.5 vs. 62.2 months, HR = 0.79, 95%CI 0.63–0.99; p = 0.039) [19]. However, dose-dense chemotherapy was more toxic, and more patients in the dose-dense therapy arm discontinued chemotherapy compared to the standard chemotherapy arm. A second randomized trial (MITO-7) failed to prove the superiority of dose-dense regimen compared to the conventionally scheduled one, albeit with reduced dose intensity of paclitaxel in the dose-dense arm as also less toxicity [20]. Of note, unlike the Japanese trial, both paclitaxel and carboplatin were scheduled in a weekly manner in MITO-7. A third trial of weekly paclitaxel also failed to prove its superiority over every 3 week paclitaxel, when patients in both arms were allowed to take bevacizumab [21]. At present conventionally scheduled (every 3 weeks) chemotherapy is still considered the standard of care.

6.2.3 Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy

Intraperitoneal chemotherapy involves administration of a part of the regimen, usually the platinum agent, directly into peritoneal cavity through a catheter. A meta-analysis of five clinical trials confirmed benefit of intraperitoneal chemotherapy in OS [22] which led to a National Cancer Institute alert recommending that intraperitoneal therapy should be considered in patients with small volume (<1 cm) or no residual disease after surgery. Subsequently one more randomized trial [23] showed an improvement in OS with intraperitoneal cisplatin plus intraperitoneal paclitaxel plus intravenous paclitaxel, delivered in a day 1 and day 8 schedule compared to standard intravenous paclitaxel and carboplatin. However, because of difference in paclitaxel schedule and cumulative dose of platinum between the 2 arms, there is some debate whether the improved results are due to intraperitoneal administration or a partial weekly schedule of administration. Intraperitoneal chemotherapy has not been adopted as a standard treatment in the majority of centers worldwide because of its difficult and specialized delivery, greater toxicity, and lingering doubts about incremental efficacy compared to intravenous chemotherapy.

The addition of a third drug to taxane-platinum and maintenance/consolidation strategies has failed to improve outcome, and should not be routinely practiced.

6.2.4 Targeted Therapy

Angiogenesis is an important component driving the growth of ovarian cancer, and targeting this pathway may improve outcome. Two randomized trials have assessed the addition of bevacizumab, a monoclonal antibody against vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), to the combination of paclitaxel and carboplatin in first-line adjuvant setting [24, 25]. Both studies reported a modest improvement in radiologically defined PFS (14.1 vs. 10.3 months in GOG 218, p = 0.001 and 24.1 vs. 22.4 months in ICON 7, p = 0.04), but no improvement in OS or quality of life. Moreover, PFS curves tended to converge after bevacizumab was stopped at protocol-defined time points (12 and 15 months, respectively, in ICON-7 and GOG-218). Planned subgroup analysis suggested a significant overall survival benefit in suboptimally cytoreduced stage III/IV patients in ICON-7 trial, but this finding can only be considered exploratory rather than practice changing. The benefit of adding bevacizumab is seen only in women at high risk of recurrence, with no benefit in women with advanced disease who are optimally debulked. No predictive biomarker for bevacizumab activity has been identified to date. The clinical benefit of adding bevacizumab to standard adjuvant chemotherapy in advanced ovarian cancer has led to adoption of this strategy in some countries, but its routine use in a first-line setting would not be considered as the current standard of care in resource-constrained settings.

7 Management of Relapsed Ovarian Cancer

Most women with primary advanced ovarian cancer (approximately 75 %) develop recurrence at a median of 1–2 years after initial diagnosis. The role of secondary cytoreductive surgery is not definitely established but may be considered in a selected group of patients with platinum-sensitive localized relapse amenable to complete resection. In patients with platinum-sensitive relapse (disease-free interval of >6 months after completion of adjuvant chemotherapy), combination platinum chemotherapy (for, e.g., paclitaxel-carboplatin, liposomal doxorubicin-carboplatin, gemcitabine-carboplatin) is standard based on an individual patient data meta-analysis, which has demonstrated improvement in OS and PFS compared to single-agent platinum [26]. In patients with platinum-resistant or refractory disease (disease-free interval <6 months after completion of adjuvant chemotherapy or progressive disease on primary treatment), single-non-platinum agent is the preferred chemotherapy option. Numerous agents like docetaxel, weekly paclitaxel, topotecan, oral etoposide, liposomal doxorubicin, capecitabine, etc., have been used with consistently low response rates of less than 20 %.

Again, addition of bevacizumab to standard chemotherapy in patients with platinum-sensitive and platinum-resistant relapsed ovarian cancer has led to modest benefits in PFS with no impact on OS [27, 28]. However, when feasible, its use may be considered in relapsed patients who have significant ascites and do not have features of intestinal obstruction. Recently poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor, olaparib, has been found to be of utility in platinum-sensitive recurrence, especially in BRCA-mutated patients [29]. However, this treatment is currently not feasible for the large majority of relapsed patients in resource-limited settings.

Table 1 shows the various management options for epithelial ovarian cancer based on resource considerations.

Table 1

Management options for Epithelial ovarian cancer (based on resource considerations)

No resource restrictions

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|

|---|