Jerome O. Klein Infection of the external auditory canal (otitis externa) is similar to infection of skin and soft tissue elsewhere. Unique problems occur because the canal is narrow and tortuous; fluid and foreign objects enter, are trapped, and cause irritation and maceration of the superficial tissues. The pain and itching that result may be severe because of the limited space for expansion of the inflamed tissue. Infections of the external canal may be subdivided into four categories: acute localized otitis externa, acute diffuse otitis externa, chronic otitis externa, and malignant otitis externa. Reviews by Senturia and co-workers,1 Hirsch,2 and Rubin and Yu3 provide more complete information. The external auditory canal is approximately 2.5 cm long from the concha of the auricle to the tympanic membrane. The lateral half of the canal is cartilaginous; the medial half tunnels through the temporal bone. A constriction, the isthmus, present at the juncture of the osseous and cartilaginous portions, limits the entry of wax and foreign bodies to the area near the tympanic membrane. The skin of the canal is thicker in the cartilaginous portion and includes a well-developed dermis and subcutaneous layer. The skin lining the osseous portion is thinner and firmly attached to the periosteum and lacks a subcutaneous layer. Hair follicles are numerous in the outer third and sparse in the inner two thirds of the canal. Cerumen and debris from epithelial cells accumulate in the canal and are extruded by normal cleansing mechanisms. On occasion, the material may become inspissated and obstruct the canal. The microbial flora of the external canal are similar to the flora of skin elsewhere. There is a predominance of Staphylococcus epidermidis, Staphylococcus aureus, Corynebacteria, and, to a lesser extent, anaerobic bacteria such as Propionibacterium acnes.4,5 Pathogens responsible for infection of the middle ear (Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, or Moraxella catarrhalis) are uncommonly found in cultures of the external auditory canal when the tympanic membrane is intact. The epithelium absorbs moisture from the environment. Desquamation and denuding of the superficial layers of the epithelium may follow. In this warm moist environment, the organisms in the canal may flourish and invade the macerated skin. Inflammation and suppuration follow. Invasive organisms include those of the normal skin flora and gram-negative bacilli, particularly Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Invasive otitis media is a necrotizing infection frequently associated with P. aeruginosa. The organism gains access to the deeper tissues of the ear canal and causes a localized vasculitis, thrombosis, and necrosis of tissues. Diabetic microangiopathy of the skin overlying the temporal bone results in poor local perfusion and a milieu for invasion by P. aeruginosa. Acute localized otitis externa may occur as a pustule or furuncle associated with hair follicles; the external ear canal is erythematous, edematous, and may be filled with pus and flakes of skin debris. S. aureus is the most frequent pathogen. Erysipelas caused by group A Streptococcus may involve the concha and the canal. Pain may be severe. Bluish-red hemorrhagic bullae may be present on the osseous canal walls and also on the tympanic membrane. Adenopathy in the lymphatic drainage areas is often present. Local heat and systemic antibiotics are usually curative. Incision and drainage may be necessary to relieve severe pain. Acute diffuse otitis externa (swimmer’s ear) occurs mainly in hot humid weather. The ear itches and becomes increasingly painful. The skin of the canal is edematous and red. Gram-negative bacilli, mainly P. aeruginosa, may play a significant role. A severe hemorrhagic external otitis caused by P. aeruginosa was associated with mobile redwood hot tub systems.6 Gentle cleansing to remove debris, including irrigation with warm tap water should reduce symptoms; alternatively, hypertonic saline (3%) and cleansing with mixtures of alcohol (70% to 95%) and acetic acid may be used. . Hydrophilic solutions, such as 50% Burrow’s solution, may be used for 1 to 2 days to reduce inflammation. A cotton wick may be of value in enhancing distribution of the ototopical agent when the canal is swollen. A 10-day regimen of a fluoroquinolone otic solution, such as ofloxacin7 or ciprofloxacin-dexamethasone otic8 or eardrops of neomycin alone or with polymyxin combined with hydrocortisone, are effective in reducing local inflammation and infection. Chronic otitis externa is caused by irritation from drainage through a perforated tympanic membrane. The underlying cause is chronic suppurative otitis media. Itching may be severe. Management is directed to treatment of the middle ear disorder. Rare causes of chronic otitis externa include tuberculosis, syphilis, yaws, leprosy, and sarcoidosis. Invasive (“malignant”) otitis externa is a severe, necrotizing infection that spreads from the squamous epithelium of the ear canal to adjacent areas of soft tissue, blood vessels, cartilage, and bone3,9 (see Chapter 221). Severe pain and tenderness of the tissues around the ear and mastoid are accompanied by the drainage of pus from the canal. Older, diabetic, immunocompromised, and debilitated patients are at particular risk. Life-threatening disease may result from spread to the temporal bone and then on to the sigmoid sinus, jugular bulb, base of the skull, meninges, and brain. Permanent facial paralysis is frequent, and cranial nerves 9, 10, and 12 may also be affected.10 P. aeruginosa is almost always the causative agent (see Chapter 221). The extent of damage to soft tissue and bone may be identified and monitored by the use of computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging.3 Diagnostic tests for underlying disease should be instituted. The canal should be cleansed, devitalized tissue removed, and eardrops with antipseudomonal antibiotics combined with steroid instilled into the external auditory canal. Systemic therapy with regimens including activity for Pseudomonas spp. should be used for 4 to 6 weeks. The combination of ceftazidime, cefepime, or piperacillin with an aminoglycoside (gentamicin or tobramycin) should be considered.10 Oral quinolones with activity against Pseudomonas spp., such as ciprofloxacin, have been effective therapy early in the course of invasive external otitis.11 Aspergillus species, particularly A. niger, may grow in the cerumen and desquamated keratinaceous debris in the external auditory canal, sometimes forming a visible greenish or blackish fluffy colony. Role of the mold in acute otitis externa is usually modest, if any, although, in the severely immunocompromised patient, Aspergillus can cause necrotizing otitis externa.12 Candida albicans is a frequent cause of external otitis in children with chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis. Acute otitis media (AOM) is defined as an acute illness marked by the presence of middle ear fluid and inflammation of the mucosa that lines the middle ear space. Otitis media with effusion (OME) is defined by the presence of middle ear fluid without acute signs of illness or inflammation of the middle ear mucosa. It usually follows AOM but may also occur as a result of barotrauma or allergy. The peak incidence occurs in the first 3 years of life. The disease is less common in the school-aged child, adolescents, and adults. Nevertheless, infection of the middle ear may be the cause of fever, significant pain, and impaired hearing in all age groups. In addition, adults suffer from the sequelae of otitis media of childhood: hearing loss, cholesteatoma, adhesive otitis media, and chronic perforation of the tympanic membrane. Three recent factors have and will alter the incidence, microbiology, and management of otitis media: 3. In 2004 and 2013, publication of management guidelines by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) presented criteria for managing AOM without antimicrobial agents.13,14 Interested readers are referred to the AAP/AAFP guidelines for management of AOM13,14 and OME15 and Otitis Media in Infants and Children by Bluestone and Klein.16 By 3 years of age, more than two thirds of children have had one or more episodes of AOM, and one third have had three or more episodes.17 The highest incidence of AOM occurs between 6 and 24 months of age. Subsequently, the incidence declines with age, except for a limited reversal of the downward trend between 5 and 6 years of age, the time of school entry. Otitis media is infrequent in adults, but the bacteriology and therapy are similar to those in children.18 Longitudinal studies have provided information about the characteristics of children who have recurrent and severe episodes of AOM. The vast majority of children have no obvious defect responsible for severe and recurrent otitis media, but a small number have anatomic changes (cleft palate, cleft uvula, submucous cleft), alteration of normal physiologic defenses (patulous eustachian tube), or congenital or acquired immunologic deficiencies. An increased incidence of AOM occurs in children with Down syndrome.19 Children with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome have a higher age-specific incidence of otitis media, beginning at 6 months of age, than uninfected children or children who initially were positive for human immunodeficiency virus antibody but who seroreverted.20 As is true for most infectious diseases of childhood, AOM occurs more often in males than in females. Correlation of the index child with severe or recurrent AOM in a sibling or parent identifies a likely genetic susceptibility. Proinflammatory cytokine gene polymorphisms and polymorphisms in immunoresponse genes were associated with recurrent AOM.21,22 The age at the time of the first episode of AOM appears to be among the most powerful predictors of recurrent middle ear infections. Breast-feeding for 3 or more months is associated with a decreased risk of AOM in the first year of life. Race and ethnicity provide additional data, suggesting a genetic basis for recurrent middle ear infections; Native Americans, Alaskan and Canadian Eskimos, and Aboriginals have an extraordinary incidence and severity of otitis media. The role of increased exposure to infectious agents and the importance of environmental pollutants have been identified in studies of the incidence of infection in group daycare and the effects of passive smoking on children. The introduction of infants into large daycare groups increases the incidence of respiratory infections, including otitis media. The daycare risk of infection is associated with the number of children in the facility. For children in large-group daycare, almost one episode of respiratory tract infections a month occurs during the first year of life, and AOM is a complication in about one third to one half of respiratory tract infections.23 Children in daycare not only have more episodes of AOM than children in home care but have more severe disease, as measured by the need for more surgical procedures. A study of Pittsburgh children observed from birth through the second year of life noted that myringotomy and tympanostomy tube placements were performed in 21% of children in group daycare and in only 3% of children in home care.24 Exposure to tobacco smoke documented by measuring a nicotine metabolite, cotinine, in saliva and urine, correlated with an increased incidence of new episodes of OME and the duration of effusion.25 Kim and co-workers26 have identified an association of invasive pneumococcal disease and otitis media with atmospheric conditions, air pollution (identified by levels of sulfur dioxide), and the isolation of respiratory viruses. The middle ear is part of a continuous system that includes the nares, nasopharynx, and eustachian tube medially and anteriorly and the mastoid air cells posteriorly. These structures are lined with a respiratory epithelium that contains ciliated cells, mucus-secreting goblet cells, and cells capable of secreting local immunoglobulins. Anatomic or physiologic dysfunction of the eustachian tube appears to play a critical role in the development of otitis media. The eustachian tube has at least three physiologic functions with respect to the middle ear: protection of the ear from nasopharyngeal secretions, drainage into the nasopharynx of secretions produced within the middle ear, and ventilation of the middle ear to equilibrate air pressure with that in the external ear canal. When one or more of these functions is compromised, the results may be the development of fluid and infection in the middle ear. Most episodes of AOM occur in the following sequence: congestion of the mucosa of the upper respiratory tract, often caused by a respiratory viral infection; swelling of the mucosa of the eustachian tube, progressing to obstruction of the tube at its narrowest section, the isthmus; secretions that are constantly formed by the mucosa of the middle ear accumulate behind the obstruction and if a bacterial pathogen is present, AOM may result. The pathogenesis of fluid that persists for weeks to months after episodes of adequately treated AOM or persistent OME remains uncertain. Recent studies have suggested that bacterial biofilms on the middle ear mucosa may play a role in chronic OME or OME.27 The bacteriology of otitis media has been documented by appropriate cultures of middle ear effusions obtained by needle aspiration. Many studies of the bacteriology of AOM have been performed. The results are remarkably consistent in demonstrating the importance of S. pneumoniae and H. influenzae in all age groups, but more recent studies, since the introduction of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, suggest that H. influenzae may replace S. pneumoniae as the most frequently isolated pathogen of AOM in children (Table 62-1).28,29 TABLE 62-1 Bacterial Pathogens Isolated from Middle Ear Fluid in Children with Acute Otitis Media, 1995-2003 * Total percentages are more than 100% because of multiple pathogens per middle ear effusion.

Otitis Externa, Otitis Media, and Mastoiditis

Otitis Externa

Pathogenesis

Clinical Manifestations and Management

Otitis Media

Epidemiology

Pathogenesis

Microbiology

Bacteria

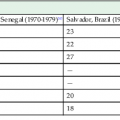

CHILDREN WITH PATHOGEN (%)*

BACTERIAL PATHOGEN

1995-2000 (N = 399)

2001-2003 (N = 152)

Streptococcus pneumoniae

28

23

Haemophilus influenzae

25

36

Moraxella catarrhalis

3.5

3

Streptococcus, group A

1.5

1.3

None or nonpathogens

46

41

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Otitis Externa, Otitis Media, and Mastoiditis

62