Other Tumors of Undefined Neoplastic Nature

Sean V. McGarry

C. Parker Gibbs

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) and Erdheim-Chester disease (ECD) are histiocytoses: rare benign lesions of bone in which the proliferating tumor cell of origin is a histiocyte. There are two types of histiocytes: (1) macrophages arising from monocytes and (2) dendritic cells arising from Langerhans cells. In LCH the involved cell is a Langerhans cell, in ECD a macrophage. Histiocytoses in general exist in multiple forms, ranging from a solitary lesion to a diffuse systemic disease, and they can affect any organ or tissue in the body. This section deals with the two histiocytoses involving bone: LCH and ECD. LCH is most commonly a solitary lesion occurring in children and young adults and often requires surgical intervention. ECD is often a systemic disease of older adults and very rarely involves surgical intervention.

Erdheim-Chester Disease

The original description of ECD was made by Chester in 1930. In 1972, Jaffe first used the eponym ECD to recognize that description. In 1983, a review of the literature by Alper found that 47 cases had been described up to that point. ECD remains an extremely rare entity; thus, our knowledge of the natural history of the disease and its treatment is somewhat limited. Its etiology is unknown.

Pathogenesis

Epidemiology

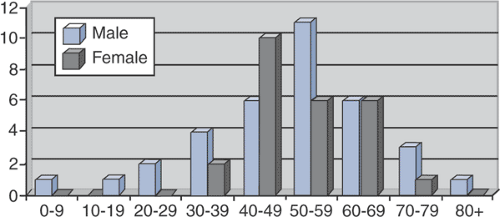

Typically a disease of older adults (Fig. 5.8-1)

Age range 7 to 84 years

Mean age 53 years

Slight male predominance

Affects long bones most commonly

Bilateral and symmetric

Classically affects diaphysis and metaphysis, sparing epiphysis (not always)

Lower extremity (femur, tibia, fibula) more common than upper extremity (humerus, radius, ulna)

Usually spares flat bones

Pathophysiology

Systemic lipid storage disorder affecting histiocytes

Lipid-laden histiocytes form granulomas in bones, other organs or tissues.

Prognosis and Natural History

Because of the infrequency of the disease, little is known about prognostic factors.

Prognosis is related to extent of visceral involvement.

In some patients the disease is quiescent.

In most patients the disease is progressive, and patients die of end-organ failure

Respiratory distress or pulmonary fibrosis

Heart failure

Renal failure

Classification

There currently is no accepted classification scheme for ECD.

Diagnosis

Physical Examination and History

A definitive diagnosis requires the combination of history, physical examination findings, radiographs, and a tissue diagnosis.

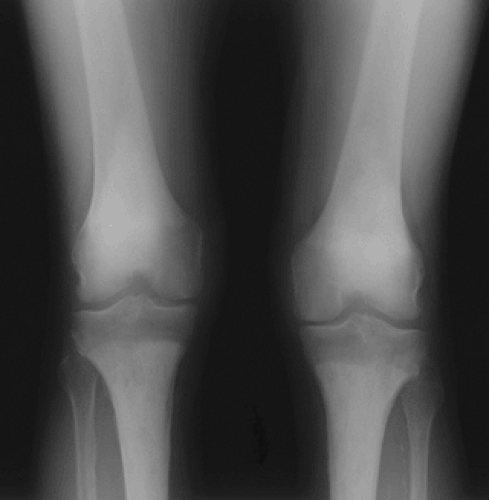

Classical radiographic findings with bilateral, symmetric osteosclerosis of the diaphysis and metaphysis with epiphyseal sparing can be considered pathognomonic.

Radiologic Features

Densely sclerotic changes of the metaphysis and diaphysis, with coarsened trabeculae

Typically spares the epiphysis

Rarely, lesions are more lytic in nature.

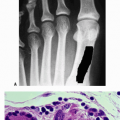

Long bones most commonly affected (Fig. 5.8-3)

Lower extremities more commonly affected than upper extremities

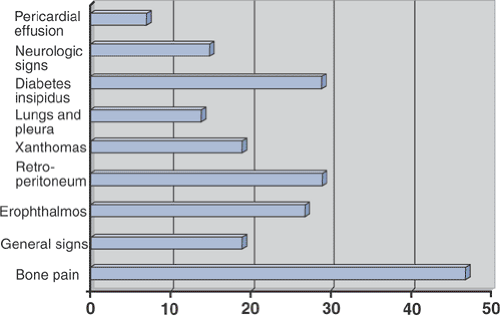

Table 5.8-1 Clinical Manifestations of Erdheim-Chester Disease According to Organ of Involvement | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

Diagnostic Workup Algorithm

Radiographs are nearly always pathognomonic for ECD.

When seen in concert with typical complaints of bone pain, exophthalmos, diabetes insipidus, or xanthomas, these patients are not a diagnostic challenge.

They can show elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, alkaline phosphatase, or serum lipid profiles.

However, laboratory testing is unreliable and nonspecific.

Figure 5.8-3 Radiograph of patient with Erdheim-Chester disease showing typical radiographic changes.

If there is any question as to the diagnosis, a biopsy of an accessible skeletal lesion is performed.

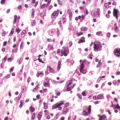

Histopathologic evaluation demonstrates infiltration of the bone by foamy, lipid-laden histiocytes, with giant cells and rare lymphocytes.

Immunostaining demonstrates negative staining for both S-100 and CD1a (which would suggest the diagnosis of LCH).

Treatment

Surgical and Nonoperative Options

Occasional need for biopsy to confirm diagnosis

No need for surgical intervention other than rare prophylactic fixation to prevent fracture

No good nonoperative treatment options, but historically patients are treated with any combination of the following:

Steroids

Chemotherapy

Radiation

Results and Outcome

Overall Outcome

With no good treatment options for ECD, overall survival is rather bleak. In a review of 37 patients followed for an average of 30 months, Veyssier-Belot reported a mortality rate of 59%. Other reports suggest a mortality rate of approximately 33%, but with limited follow-up. Patients die of end-organ failure (pulmonary fibrosis, heart failure, or renal failure most commonly).

Specific Treatment Outcome

Because there is not a consensus as to the appropriate treatment of ECD in combination with the rarity of the diagnosis, there are not sufficient numbers to assess specific treatment outcomes. In the review by Veyssier-Belot, the following results are presented:

Steroid therapy alone in 12 patients

Effective transiently in 4 patients

Ineffective in 8

Chemotherapy in combination with steroids in 8 patients

4 patients improved

No effect in 4 patients

Radiation therapy in 6 patients

Transiently effective in 3 for bone pain

Not effective in 3 to treat exophthalmos

Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis

In 1953, Lichtenstein, noting the histological similarities in eosinophilic granuloma, Hand-Christian-Schüller, and Letterer-Siwe, coined the term “histiocytosis X” as a general term to encompass all three diagnoses. We know today that all three diseases originate from a Langerhans cell and refer to the group of disorders as the Langerhans cell histiocytoses (LCH) or granulomatoses. The three share a common histopathology and are considered to be clinical variations of the same disease.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree