Introduction

Dementia is an acquired syndrome in which there is impairment of cognitive abilities, severe enough to interfere with the individual’s occupational, social and functional abilities. As conventionally used, the term dementia implies ‘degenerative’ and ‘progressive’, but it is also often used in the context of static conditions (such as post-stroke cognitive impairment) or reversible conditions (such as depression or medication-related cognitive impairment). Table 79.1 provides a list of the many causes of dementing illnesses that can occur in older individuals.

Table 79.1 Causes of dementia other than Alzheimer’s disease.

1. Other degenerative dementias a. Dementia with parkinsonism i. Diffuse Lewy body disease ii. Parkinson’s disease dementia iii. Progressive supranuclear palsy iv. Corticobasal degeneration v. Multiple system atrophy b. Frontotemporal dementia c. Huntington’s disease d. Hallervorden–Spatz disease e. Kufs’ disease 2. Vascular dementia 3. Other CNS causes a. Normal-pressure hydrocephalus b. Epilepsy c. Traumatic dementia i. Acute and chronic subdural haematoma ii. Dementia pugilistica iii. Craniocerebral injury d. Tumours i. Primary CNS tumours: gliomas, meningiomas ii. Metastatic tumours, lymphoma, leukaemia iii. Paraneoplastic limbic encephalitis 4. Psychiatric disorders a. Depression b. Others: schizophrenia, mania, other psychoses 5. Inflammatory a. Cerebral vasculitis i. Primary angiitis of the CNS ii. Part of systemic involvement: disseminated lupus erythematosus, temporal arteritis, Behçet’s disease, Wegener’s granulomatosis, Churg–Strauss disease b. Multiple sclerosis 6. Metabolic a. Endocrinopathies i. Hyper- and hypothyroidism ii. Glucose disorders: hyper- and hypo- states iii. Cushing’s disease iv. Addison’s disease b. Electrolyte abnormalities i. Hypo- and hypernatraemia ii. Hypercalcaemia c. Inherited i. Wilson’s disease ii. Mitochondrial disorders iii. Adult lysosomal diseases (particularly metachromatic leukodystrophy) iv. Peroxisomal disorders 7. Nutritional deficiency a. Thiamine deficiency b. Vitamin B12 deficiency c. Folate deficiency d. Vitamin B6 deficiency (pellagra) 8. Infective a. Neurosyphilis b. Human prion disease c. HIV-associated dementia d. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy e. Post-meningitic/post-encephalitic dementia 9. Drugs (remembered by the mnemonic ACUTE CHANGE IN MS30) a. Antiparkinsonian drugs b. Corticosteroids c. Urinary incontinence drugs d. Theophylline e. Emptying (motility) drugs f. Cardiovascular drugs g. H2 blockers h. Antimicrobials i. NSAIDs j. Geropsychiatric drugs k. ENT drugs l. Insomnia drugs m. Narcotics n. Muscle relaxants o. Seizure drugs 10. Toxins a. Alcohol b. Heavy metals: lead, aluminium, mercury c. Carbon monoxide poisoning 11. Others a. Obstructive sleep apnea b. Whipple’s disease c. Neurosarcoidosis |

Because Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is widely reported as the commonest cause of dementia worldwide, it may be tempting for clinicians to make this diagnosis routinely without systematically considering alternative or additional diagnoses. Such a practice, although probably fortuitously correct most of the time, would fail to detect reversible diseases that affect cognition (which often occur concomitantly with AD) and other non-AD aetiologies that may confer different prognosis and necessitate different treatment modalities from AD.

Population-based studies on Western and Asian cohorts indicate that vascular dementia (VaD) is often the commonest reported dementia aetiology after AD. When actively sought for with standard criteria, the prevalence of dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) and frontotemporal dementia (FTD) may be higher than previously thought. For example, the Islington study of community-dwelling elderly revealed the following distribution of dementia subtypes: AD 31.3, VaD 21.9, DLB 10.9 and FTD 7.8%.1 Specialized memory clinic-based estimates differ somewhat from population-based studies in having a relatively higher prevalence of non-AD aetiologies and concomitant potentially reversible conditions, especially depression and metabolic abnormalities. Generally, however, only a small percentage of these conditions have been found to be completely reversible, most notably hypothyroidism and vitamin B12 deficiency. The prevalence of aetiologies in demented patients presenting to private practitioners has not been estimated, but would likely reflect values intermediate between population- and specialized outpatient-based estimates.

This chapter discusses some conditions that are commonly encountered in clinical practice, notably vascular cognitive impairment and non-AD neurodegenerative dementias. We focus on conceptual advances and clinical gems that can help in the diagnosis and management of these conditions and conclude with a general approach to the evaluation of dementia with parkinsonism.

Vascular Cognitive Impairment/Vascular Dementia

Epidemiological studies in the West indicate that VaD is second in prevalence to AD, accounting for 12–20% of dementia cases. The incidence of VaD increases with age, but much less steeply than AD. Unlike AD, men are disproportionately more affected, especially at younger ages. Earlier international comparative studies revealed a higher frequency of VaD in Asian countries, notably Japan and China. The ratio of AD to VaD varied from 1.4 in Beijing, China, to 2.8 in Korea, compared with the ratio of 3.4 in Europe. However, a recent study from China reported a higher prevalence of AD than VaD (3.5 versus 1.1%) in the population older than 65 years.2 Whether this portends an epidemiological shift towards Western trends or is due to methodological differences is unclear.

Despite being described by Alois Alzheimer more than a century ago, the role of cerebrovascular disease (CVD) in dementia has been dogged by misconception. For the greater part of the twentieth century, it was commonly held that the most frequent cause of late-onset dementia was arteriosclerosis. Seminal work in the late 1960s challenged this assumption, establishing that the main type of pathology underlying late-onset dementia was degenerative and of Alzheimer type rather than vascular. This led to a redefinition of late-onset dementia as primarily the result of AD, with the result that the nosological status of vascular dementia became uncertain.

The field moved forward when the concept of multi-infarct dementia (MID) was described to reflect dementia due to multiple large and small strokes. The field further evolved with the recognition that MID was just one of many subtypes of VaD (Table 79.2).3 VaD encompasses several clinicopathological subtypes, ranging from haemorrhagic (including hypertension, cerebral amyloidal angiopathy, subarachnoid haemorrhage, post-haemorrhagic obstructive hydrocephalus, subdural haematoma and haematological causes) to ischaemic and combinations of ischaemia and haemorrhage (such as cortical vein and sinus thromboses). Ischaemic forms of VaD can be further divided into large-vessel, small-vessel and strategic infarct subtypes (Table 79.2). Among the hereditary group, the most extensively studied condition is cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL), a genetically transmitted small-vessel disorder that has been mapped to chromosome 19q12 with mutations in the Notch 3 gene.

Table 79.2 Subtypes of vascular dementia (VaD).

| Subtype | Description |

| Multi-infarct dementia (cortical VaD) | Predominantly resulting from large cortical infarcts |

| Small-vessel dementia (subcortical VaD) | Predominantly resulting from subcortical lacunes, white and/or deep grey matter lesions |

| Strategic infarct dementia | Resulting from a unilateral or bilateral infarct in a strategic area |

| Hypoperfusion dementia | Resulting from brain damage due to hypoperfusion |

| Haemorrhagic dementia | Resulting from intracerebral haemorrhage |

| AD with CVD | Presence (or presumption on the basis of clinical picture and brain imaging) of both significant Alzheimer and vascular pathology, both of which are thought to contribute to dementia |

| Hereditary dementia | Genetic causes of VaD, such as CADASIL due to mutation in the NOTCH 3 gene in chromosome 19 |

To make a diagnosis of VaD, three elements are necessary: presence of dementia, presence of cerebrovascular lesions and a temporal relationship between the two. Traditional diagnostic criteria for VaD can be broadly divided into two groups.4 The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV), and the Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders, 10th Revision, under the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10), are general diagnostic tools that outline criteria without operationalizing them. The second set, such as the widely used National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and the Association Internationale pour la Recherche et l’Enseignement en Neurosciences (NINDS–AIREN) criteria (Table 79.3),5 is a development of the first two and offers operational criteria. Autopsy studies have shown that although these criteria are generally able to exclude about 90% of AD, they have only modest sensitivity (50–70%) in diagnosing VaD. There is a tendency to misclassify mixed dementia (AD with CVD) as VaD (54% for ADDTC and 29% for NINDS–AIREN), especially in the ‘possible VaD’ category. Application of the NINDS imaging criteria also did not distinguish between demented and non-demented patients.

Table 79.3 NINDS–AIREN criteria for probable and possible vascular dementia (VaD).5.

| Probable VaD |

1. Dementia 2. Cerebrovascular disease

3. Temporal relationship between dementia and CVD, as evidenced by one or more of the following:

Clinical features consistent with diagnosis:

Criteria for relevant cerebrovascular disease on brain imaging

|

| Possible VaD |

1. Dementia with focal neurological signs but without neuroimaging confirmation of definite CVD 2. Dementia with focal signs but without a clear temporal relationship between dementia and stroke 3. Dementia and focal signs but with subtle onset and variable course of cognitive deficits |

| Alzheimer’s disease with cerebrovascular disease |

1. Clinical criteria for possible AD 2. Clinical and imaging evidence of CVD |

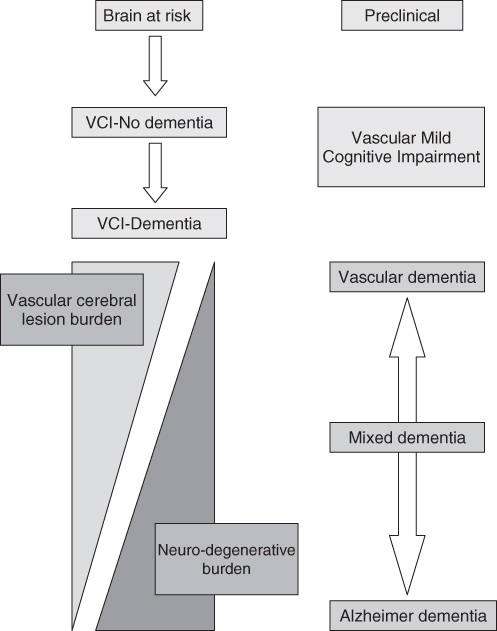

Advances in the past decade have consolidated our understanding of the contribution of CVD in cognition in three key areas.6 First, vascular cognitive impairment (VCI) is a more comprehensive and appropriate concept than VaD. VCI is an umbrella term that includes VCI-no dementia, VaD and mixed dementia (Figure 79.1). About 5% of VCI people over the age of 65 are estimated to have VCI; in patients under 74, VCI may be the single most common cause of cognitive impairment.7 The inclusion of VCI-no dementia, a subset with less severe cognitive impairment that do not meet formal criteria for dementia, is analogous to the concept of the pre-dementia stage of amnestic MCI in AD and serves to emphasize the preventable nature of VCI and the importance of early diagnosis. This concept can be taken further: while the progression of VCI is analogous to secondary prevention, primary prevention requires the recognition of the presence of risk factors in an asymptomatic susceptible host, termed ‘brain-at-risk’.

Figure 79.1 Schematic diagram depicting the spectrum of vascular cognitive impairment (VCI) and the overlap between vascular dementia (VaD) and neurodegenerative disease using Alzheimer’s disease (AD) as an example. In this conceptual model, AD and VaD fall on a continuous spectrum of disease. The gradient of features, driven by the underlying burden of vascular (lacunes, white matter disease and cerebral microhaemorrhage) and neurodegenerative (amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles) pathology, would then determine the phenotype and nosologic classification (VaD, mixed or AD).

Second, with increasing recognition of the overlap between AD and VCI in terms of predisposing factors and pathophysiology, these two disorders are currently conceptualized as a continuous spectrum rather than coexisting unrelated conditions (Figure 79.1).8 Apart from the ends of the spectrum where pure AD or pure VaD lie, mixed dementia constitutes the majority of patients who cannot easily be classified as being in one group or the other. Limited data suggest that patients with mixed dementia outnumber those with pure AD.6 Within the mixed group, vascular brain injury acts additively or synergistically with concomitant AD pathology to produce more severe cognitive dysfunction than either process alone. In support of this, clinicopathological data such as the Nun Study indicate that subjects with both vascular disease and AD pathology exhibit either more severe cognitive impairment during life than those with pure AD or require less pathology to produce the same amount of cognitive impairment. This suggests that in AD patients with concomitant CVD, both conditions require treatment, even if the vascular component may appear trivial.

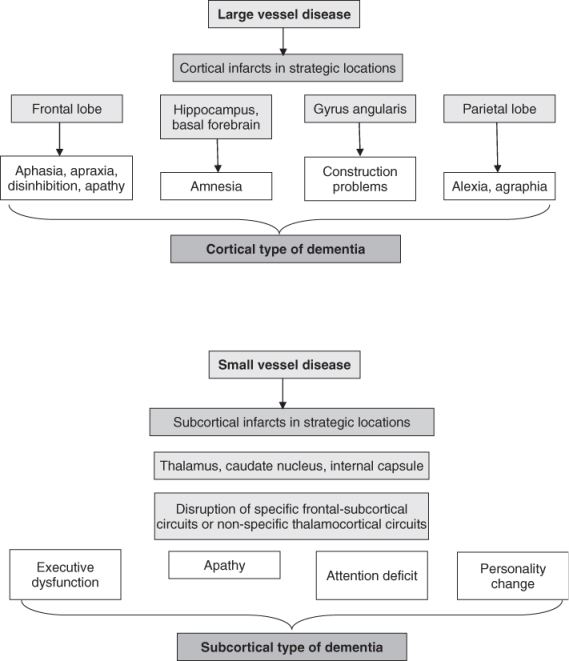

Third, our understanding of the pathophysiology of VCI has evolved to distinguish VCI associated with large vessel disease from that associated with small vessel disease, including subcortical ischaemic vascular disease (SIVD) and non-infarct ischaemic changes such as leukoaraiosis. SIVD includes the lacunar state and Binswanger’s disease, characterized, respectively, by multiple lacunes and periventricular leukoencephalopathy that typically spares the arcuate subcortical U fibres. Limited data from clinical samples indicate that SIVD is the most common subtype.4 A recent study reported that 82.2% had small-vessel VaD whereas only 25.9% had large-vessel VaD.

Although there is some degree of overlap, large-vessel strokes tend to yield a clinical picture of cortical dementia, as opposed to the subcortical dementia of small-vessel forms (Figure 79.2). These can be reasonably differentiated by a combination of cognitive features, neurological features and clinical course (Table 79.4).9 SIVD typically causes a slow, subacute-onset dementia that is characterized by executive dysfunction, impaired attention and impaired processing speed, with a comparatively milder memory deficit. There may be ‘lower-half parkinsonism’ producing characteristic gait changes of hesitation, marche à petit pas (walking with hurried small steps) and diminished step height. In fact, the triad of dementia, urinary incontinence and gait disturbance, is more often produced by small-vessel VaD than normal-pressure hydrocephalus (NPH). Neuropsychiatric disturbances such as depression, anxiety, agitation, disinhibition and apathy are not uncommon in VaD, especially the small-vessel subtype.

Table 79.4 Characteristics of cortical and subcortical dementia.

| Clinical feature | Cortical | Subcortical |

| Cognitive deficits | Memory impairment prominent | Executive dysfunction prominent |

| Heteromodal cortical symptoms | Memory deficit milder | |

| Neuropsychological syndromes | Perseveration | |

| Executive dysfunction usually present | Mood changes (depression, emotional lability, apathy) | |

| Neurological symptoms | Field cut Lower facial weakness Upper motor neuron signs Dominant/non-dominant lobe signs | Imbalance/falls Gait disturbance Altered urine frequency Mild upper motor neurone signs |

| Dysphagia | ||

| Extrapyramidal signs | ||

| Clinical course | Abrupt onset | 60%: slow, less abrupt onset |

| Stepwise deterioration | 80%: slow progression with or without stepwise decline | |

| Fluctuating course with plateaux |

Dementia may occur in 25–33% of ischaemic stroke cases at ages 65 years and older. Predictors of the occurrence of dementia following stroke include older age, lower education level, non-White race, pre-existing cognitive decline, ‘silent’ infarcts on neuroimaging, ischaemic rather than haemorrhagic strokes, hemispheric rather than brainstem or cerebellar lesions, left rather than right hemispheric lesions, larger and recurrent strokes and more severe neurological deficit on admission. The number of vascular risk factors might be more important for predicting cognitive impairment than any individual factor. Apolipoprotein ε4 has been associated with increased risk for AD and mixed dementia, but not VaD. Leukoaraiosis may be an important predictor of cognitive decline in domains affected by cerebral small-vessel disease. There has been a continuing debate on whether periventricular or deep leukoaraiosis is more damaging to cognition. In the Rotterdam Study, periventricular leukoaraiosis and infarcts but not subcortical white matter lesions were correlated with a decline in processing speed and general cognition.10 The number of cerebral microbleeds as diagnosed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study may be an independent predictor of cognitive impairment and severity of dementia. Patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) may be at risk for both early (within 1 month) and late (beyond 5 or more years) cognitive decline. A recent observational study suggests that late cognitive decline after CABG is not specific to the use of cardiopulmonary bypass, because nonsurgical cardiac comparison patients also showed mild late cognitive decline.10

Management of VaD is multi-pronged and involves (1) symptomatic treatment for cognition, (2) management of neuropsychiatric disturbances, (3) stroke prevention strategies and (4) management of stroke-related disabilities such as spasticity, parkinsonism and incontinence. To date, three studies of donepezil in VaD and two of galantamine (one in VaD, the other in mixed dementia and VaD) have been completed.7 A modest improvement in cognition analogous to 3 points on the ADAS-Cog has been found, but effects on other outcomes such as activities of daily living, behaviour and global assessment are inconsistent. Two studies in VaD of memantine, an NMDA antagonist that protects against glutamate-mediated excitotoxicity, show modest benefits in cognition, but no benefit on a global outcome measure. Depression is common in association with stroke and SIVD and is an eminently treatable condition; hence a course of antidepressant is justifiable if there is a suspicion of concomitant depression. Levodopa can be helpful in the treatment of apraxic gait in SIVD if the burden of vascular disease lies in the basal ganglia or substantia nigra.

Strategies for stroke prevention include anticoagulation in patients at risk of cardioembolism, antiplatelet agents, targeting modifiable risk factors (such as hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidaemia and metabolic syndrome) and optimizing lifestyle factors (such as smoking cessation, physical activity, addressing mid-life obesity and fish consumption). Observational studies suggest a role for vitamin B12, folic acid and homocysteine in VCI, although rigorous intervention studies are lacking.10 Some studies suggest that treatment of hypertension may reduce the risk of incident dementia, although the recent HYVET-COG study of those aged ≥80 years treated with indapamide with option of perindopril or placebo found no effect on dementia. Despite the benefit of statins in reducing stroke by 30%, this did not translate into benefits in cognition in the PROSPER study.

In the later stages of disease, VaD is often associated with a greater degree of physical, behavioural and functional issues than in AD. The goal of treatment is then shifted to the alleviation of morbidity and caregiver burden and a multidisciplinary team input is often required.

Lewy Body Disease

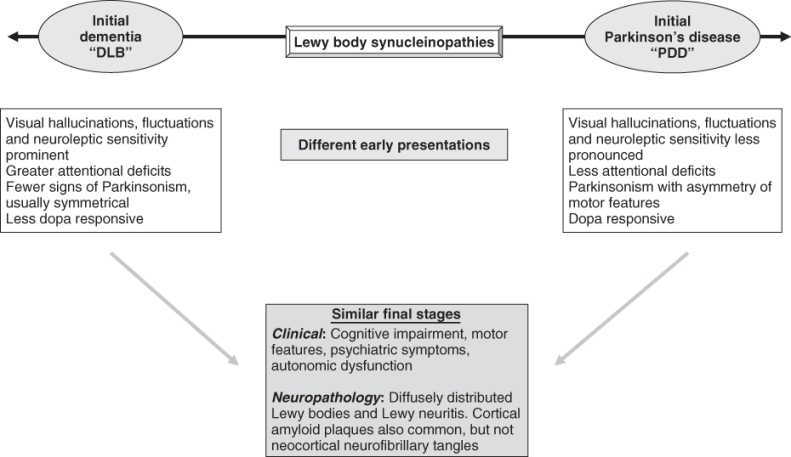

There is growing appreciation that dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) and Parkinson’s disease dementia (PDD) are actually part of the spectrum of Lewy body disease (LBD).11 Differences in early disease presentation in DLB and PDD gradually merge into a similar common pathway as the disease progresses, such that they share identical features in the end stage (Figure 79.3). The hallmark of both diseases is the presence of Lewy bodies, which are related to dysregulation of the synaptic protein, α-synuclein and suggest neurobiological links with other synucleinopathies such as multiple system atrophy (MSA). Recent evidence suggests that it is the presynaptic α-synuclein aggregates, rather than Lewy body pathology, that are synapto-toxic and cause neurodegeneration in LBD.

Figure 79.3 Schematic representation depicting how dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) and Parkinson’s disease with dementia (PDD) represent different points in the spectrum of Lewy body disease. Although the initial clinical manifestations of DLB and PDD differ, they are often indistinguishable in terms of clinical and neuropathological features by the end stage.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree