Osteosarcoma

Francis R. Patterson

Osteosarcoma is the most common sarcoma of bone in young people. While relatively rare compared to other orthopaedic disorders, an appropriate level of suspicion must be maintained for osteosarcoma as a source of pain in this age group. When diagnosed early and treated appropriately, survival with a highly functional limb can often be achieved in this age group. Most osteosarcoma patients present with pain as the initial symptom, but some patients first notice this after an injury or falsely attribute their symptoms to a minor trauma. Therefore, pain that does not improve in the expected time period, or pain that is worsening despite treatment or rest, should raise a red flag, and an appropriate work-up, starting with plain radiographs, must be pursued. Osteosarcoma has a bimodal distribution with a second but smaller peak in late adulthood. Adult osteosarcomas are often secondary to conditions such as Paget’s disease or prior radiation (Table 6.1-1). After biopsy, the standard treatment of osteosarcoma includes preoperative chemotherapy, followed by resection, and postoperative chemotherapy when appropriate.

Pathogenesis

Etiology

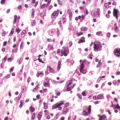

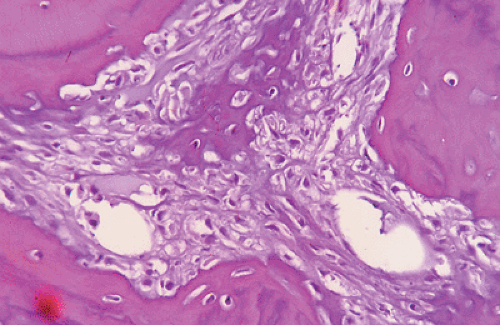

Osteosarcoma is a tumor composed of a malignant spindle cell stroma (background) with malignant osteoblasts

that produce tumor osteoid (collagenous immature bone that appears pink on hematoxylin-and-eosin [H&E] staining) or bone (Fig. 6.1-1).

Table 6.6-1 Comparison of Vascular Sarcomas of Bone

Sarcoma Type

Age

Gender

Anatomic Distribution

Gross Appearance

Histologic Features

Other Details

Hemangioendothelioma

First through ninth decades

M > F (slightly)

Half involve lower extremity; any bone affected

Firm, friable, bloody

Well-formed vascular spaces (“staghorn spaces”) lined by plump endothelial cells.

Intermixed with corded pattern mimicking carcinoma.

Multicentricity common; one third of cases multifocal

Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma

Second through eighth decades; peaks in second and third decades

M > F (slightly)

Femur most common; any bone affected

Firm, lobulated, tan

Corded, nested, or stranded pattern of plump endothelial cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm within hyalinized stroma (see Fig. 6.6-1).

May form narrow vascular channels.

Occasional cytoplasmic vacuoles (represent primitive blood vessel lumina).

Signet ring-like appearance.

Angiosarcoma

Peaks in fourth decade

M > F (slightly)

Long tubular bones and spine most common; any bone affected

Firm, bloody

Less vasoformative than hemangioendotheliomas.

Regions with vascular differentiation and plump malignant endothelial cells.

Some areas may show epithelioid appearance.

As is the case with most sporadic occurring malignancies, the factors that lead to the development of an osteosarcoma are largely unknown.

Most likely, a mutation or group of mutations occurs that leads to uncontrolled growth of the mutant cells.

Evidence exists to support the role of genetic abnormalities in patients with osteosarcoma, though these abnormalities are not identified in most patients.

Figure 6.1-1 H&E stain shows a malignant spindle cell (osteoblast) stroma with lace-like (pink) osteoid and calcified (darker) osteoid in center, typical of a high-grade osteosarcoma.

Two tumor suppressor genes may play a significant part in tumorigenesis in osteosarcoma: p53 (chromosome 17) and Rb (chromosome 13).

Reported familial patterns of osteosarcoma

Chromosome 13:14 rearrangement in sisters

Deletion of part of chromosome 13 resulting in inactivation of the retinoblastoma (RB) gene in cousins

Two genetic conditions that predispose to development of osteosarcoma

Retinoblastoma patients

May have germline mutation of Rb gene

Increased risk of osteosarcoma

Li-Fraumeni syndrome (a familial cancer syndrome; p53 gene abnormalities)

Increased risk of osteosarcomas and other malignancies

Mothers of children with sarcomas have up to a three times increased risk of breast carcinoma.

Epidemiology

Osteosarcoma is the most common type of bone sarcoma. It is neither the most common primary bone malignancy nor the most common malignancy affecting bone. The most common primary bone malignancy is multiple myeloma, and the most common malignancy affecting bone is metastatic carcinoma.

Bimodal peak age incidence

Crude incidence: 0.3 per 100,000 per year in United States (roughly 900 per year)

Majority occur within the second decade (∼60%)

Most occur at age <30 (∼85%)

Second peak age >55; often secondary osteosarcomas (e.g., Paget’s sarcoma or postradiation sarcoma)

Classic secondary osteosarcomas represent 5% to 7% of all osteosarcomas; usually with worse prognosis.

Definition: osteosarcomas that occur in relation to previous exposures or procedures as well as in the presence of other primary diseases

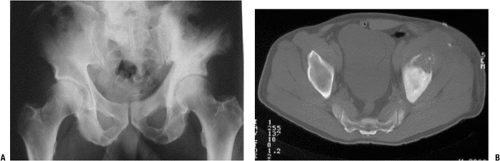

Paget’s osteosarcoma (Fig. 6.1-2)

Most common of the “secondary osteosarcomas”

Estimated 1% of Paget’s patients may develop osteosarcoma

Majority in polyostotic Paget’s, although they do occur in monostotic disease

Reports as high as 5% of polyostotic symptomatic patients

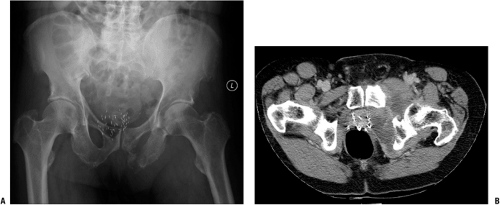

Postradiation osteosarcomas occur in bone that is in a previously irradiated field (Fig. 6.1-3).

Usually >3 years after exposure

May occur decades after treatment for other malignancies or after high-dose exposure

Disease-associated osteosarcomas

Pathophysiology

Local Growth

Osteosarcomas usually arise within the metaphyseal region of long bones. They may be located within the bone or on the surface of the bone. If untreated, osteosarcomas will continue to grow, with local destruction of bone and extension outside the bone into the surrounding soft tissues. The physis and articular cartilage may act as a relative barrier to tumor extension, but epiphyseal or intra-articular extension is still seen frequently.

Metastases

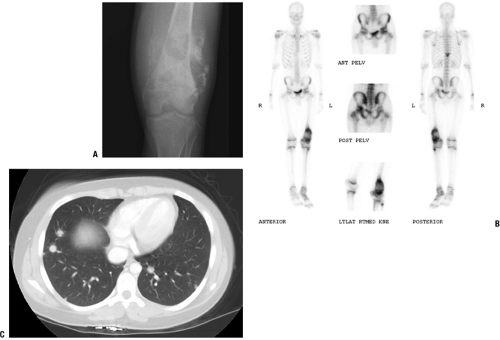

Osteosarcomas, as with all sarcomas, usually metastasize hematogenously.

Lymph node metastases are not common and usually present only very late in the course of metastatic disease.

15% to 20% of patients present with metastases at time of diagnosis.

Most common site of metastasis: lungs (Fig. 6.1-4)

Second most common: bone

Skip lesions: distinct smaller areas apart from primary tumor within same bone

Prognosis: same as or worse than distant metastases (lung or bone)

Death

Occurs most commonly due to respiratory failure secondary to widespread pulmonary metastases, but also due to other sequelae of tumor burden

Superior vena cava obstruction

Pneumonia

Hemorrhage into tumor

Sepsis

Chemotoxicity (1% to 5%)

Classification

Osteosarcoma and Variants

“Classic” osteosarcoma, also referred to as conventional osteosarcoma, and central high-grade osteosarcoma represent the majority of osteosarcomas (up to 75% in some series). Variants of osteosarcomas exist that present differently, have unique radiographic and histologic characteristics, may be treated differently, and may convey a worse or better prognosis than conventional osteosarcoma. It is important that these differences are identified and understood so that correct diagnosis and treatment may be rendered.

Pathology

Osteosarcoma is classically described as a high-grade spindle cell sarcomatous stroma with malignant osteoblasts that produce malignant osteoid or bone. The tumor cells are typically anaplastic (less differentiated), may show marked atypia and pleomorphic (widely variable) nuclei, and may show many and/or bizarre mitoses. There may be areas of osteoblastic (osseous), fibroblastic (fibrous), or chondroblastic (cartilage) appearance, but if there is the presence of malignant osteoid (wavy, lace-like, uncalcified bone matrix produced by malignant osteoblasts), the diagnosis of osteosarcoma is made regardless of the associated areas.

Grade

The grade of an osteosarcoma is used to:

Plan treatment: low-grade sarcomas are not treated with chemotherapy

Predict prognosis: low-grade osteosarcomas are less likely to develop metastases

Most osteosarcomas are high-grade tumors.

Low- and intermediate-grade osteosarcoma variants do exist (Box 6.1-1).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree