Chapter 65 Oropharyngeal Disease

Oral lesions are common throughout the course of HIV infection. They may represent theinitial signs of infection in the undiagnosed individual or they may occur in patients with well-established disease. Severe pain and loss of dental function as a result of oral disease processes can significantly alter the patient’s ability to sustain proper nutritional intake, to take oral medications, and to communicate effectively. Although the use of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) has significantly reduced the incidence of opportunistic infections in general, oral lesions continue to occur and may be useful as clinical markers of disease progression.1,2

FUNGAL INFECTIONS

Superficial Diseases

Oropharyngeal candidiasis is the most common intraoral lesion among human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected individuals (see Chapter 46). Reports indicate prevalence varying from less than 5% in adults living with HIV in developed countries to greater than 50% in those in the developing world.3,4 Predominantly caused by Candida albicans,5 this localized fungal infection is often a presenting sign of HIV infection. Closely associated with a low CD4+ T-lymphocyte count and high viral load,6,7 it is a marker for progression of HIV disease.8–10

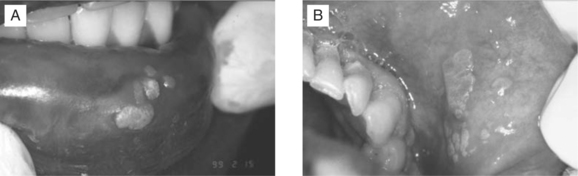

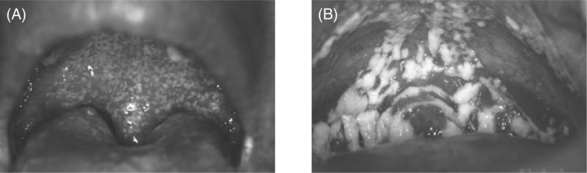

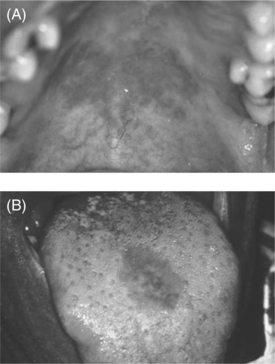

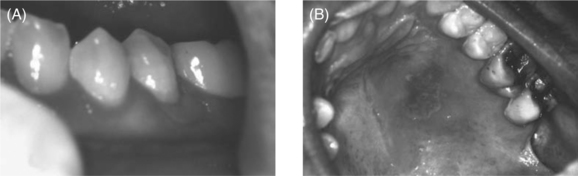

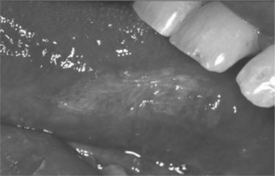

Four distinct clinical presentations of oral candidiasis can be seen: pseudomembranouscandidiasis (Fig. 65-1), erythematous candidiasis (Fig. 65-2), hyperplastic candidiasis, and angular cheilitis (Fig. 65-3). Diagnosis is based on clinical appearance of the lesions, and may be confirmed by the presence of hyphae on a potassium hydroxide preparation.

Figure 65-1 (A) Moderate-severe pseudomembranous candidasis. (B) Azole-resistant, severe pseudomembranous candidasis.

Reprinted from the International AIDS Society-USA, From Reznik DA. Oral manifestations of HIV disease. TOP HIV Med 13:143, 2005.

Figure 65-2 (A) Erythematous candidasis on the roof of the mouth. (B) Erythematous candidiasis on the tongue.

Reprinted from the International AIDS Society-USA, from Reznik DA. Oral manifestations of HIV disease. TOP HIV Med 13:143, 2005.

Figure 65-3 Angular cheilitis at the corner of the mouth caused by Candida species.

Reprinted from the International AIDS Society-USA, from Reznik DA. Oral manifestations of HIV disease. TOP HIV Med 13:143, 2005.

Pseudomembranous oral candidiasis presents as a creamy-white plaque that can be scraped off mucous membranes with a tongue blade or cotton gauze, often leaving an erythematous surface beneath (Fig. 65-1A). Patients may complain of a mild burning sensation or a foul or metallic-like taste. The most common sites are the buccal mucosa, ventral tongue or floor of the mouth, and palate (Fig. 65-1A), but the lesions may appear anywhere in the oral cavity. Severe cases may lead to difficulty in eating or swallowing (Fig. 65-1B).

Erythematous oral candidiasis may be seen as a red macular lesion of the dorsal tongue, hard palate (Fig. 65-2A), or buccal mucosa. This form of oral candidiasis may appear as an erythematous, atrophic or ‘bald’ area of the middle of the dorsum of the tongue (Fig. 65-2B). This represents a loss of filiform papillae, which should regenerate with proper treatment. Patients may complain of a burning sensation when eating salty, spicy or acidic foods.

Angular cheilitis presents as erythematous fissured, scaly patches at the angles of the mouth, with or without a pseudomembranous covering (Fig. 65-3). These sometimes painful lesions may appear unilaterally or bilaterally.

Therapy

Patients can be treated with topical, oral or intravenous regimens. Adherence, drug interactions, ability to take oral drugs, and likely fungal susceptibility results should influence the choice of agent. Topical therapy can be used for the treatment of mild to moderate episodes of pseudomembranous or erythematous candidiasis in which there is no esophageal involvement, although most clinicians choose systemic therapy.13 Effective topical agents include clotrimazole (10 mg) oral troches, nystatin (200 000 U) oral pastilles, nystatin (100 000 U) vaginal troches, which have the advantage of not containing sugars, and nystatin swish and swallow (100 000 U/mL), which has a high sucrose content. The troches or pastilles are dissolved slowly in the mouth four to five times a day, for 14 days. Nystatin swish and swallow should be held in the mouth as long as possible four times a day for the 2 week treatment period. Topical preparations that contain high sugar content can exacerbate preexisting dental decay. The use of daily fluoride preparations should be employed to help reduce the risk of dental caries. Dentures should be removed during administration of the drug. The acrylic portion of dentures or partial dentures may also harbor fungus and should be thoroughly cleaned and disinfected, with either a 1–10 parts sodium hypochlorite and water solution, a 50% dilution of 0.12% chlorhexidine suspension and water, or nystatin suspension prior to re-insertion.

Systemic therapy should be reserved for moderate to severe cases of oropharyngeal candidiasis or in cases where patients cannot adhere to the multiple dosing involved with topical preparations. Systemic treatment is also warranted in cases where lesions are nonresponsive to topical therapy, following a review to verify proper regimen and patient compliance. Toxicities of oral azoles include headache, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, skin rash, and hepatotoxicity.14 The recommended treatment duration is 14 days. Chronic suppressive therapy is indicated only if recurrences are frequent or severe.

Fluconazole is currently the preferred agent worldwide. Most clinicians use 200 mg PO as a loading dose to result in plasma concentrations close to steady state by the second day of therapy, followed by 100 mg PO/day for the remainder of the 14 day treatment period. Clinical evidence of oropharyngeal candidiasis generally resolves within several days, but treatment should be continued for at least 2 weeks to decrease the likelihood of recurrence. If the oral suspension (50 mg/5 mL or 200 mg/5 mL) is used, patients should swish and swallow 5 mL once a day. Fluconazole like the other azoles is metabolized by the cytochrome P450 system and can cause drug interactions, although much less frequently than other azoles used in the management of oral candidiasis. There have been increased reports of cases of oral infection with Candida species other than C. albicans, which are often inherently not susceptible to fluconazole (e.g., C. glabrata). Such cases may require alternative antifungal therapy (see Chapter 46).

Fluconazole-refractory oral candidiasis (FROC; Fig. 65-1B)is defined by failure to resolve within 14 days with treatment of 200 mg fluconazole per day, although this reflects dose-dependent resistance and can be temporarily overcome with doses of up to 800 mg/day. Factors associated with the development of FROC include CD4+ T-lymphocyte count <50 cells/μL, prior use of fluconazole, and frequent recurrences of candidiasis.15,16 Voriconazole and posaconazole have good anticandidal activity and can be used as first-line therapy in FROC.17,18 If oral agents are not effective in managing FROC, then the treatment of choice is an IV echinocandin class medication, such as caspofungin, or a liposomal amphotericin B.

Other Fungal Infections

Aspergillus species, Mucor, Cryptococcus, and Histoplasma occasionally can cause local invasion of oropharyngeal and nasal pharyngeal structures, and may be the initial presentation of these systemic fungal infections. Diagnosis is established by identification of characteristic organisms through biopsy and histologic examination. Cryptococcosis may present as a crater-like, nonhealing ulcer that is tender to palpation. Intraoral histoplasmosis may appear as a solitary, painful ulceration of several weeks duration with firm, rolled margins. Lesions present as white or erythematous areas with an irregular surface on the tongue, palate, and buccal mucosa.21,22 All oral ulcerations that do not respond to traditional therapy should be biopsied.

Aspergillus, Zygomyces, and Geotrichum candidum can manifest as maxillary alveolar and/or palatal swelling.21,23 A black, necrotic ulceration may be seen. Tissue damage to the maxillary sinus following tooth extraction or endodontic procedures, especially in the maxillary posterior region, can provide a portal of entry, but in most cases no predisposing anatomic factor can be found. These invasive fungal infectionsmay initially present as localized pain and tenderness accompanied by nasal discharge.

VIRAL INFECTIONS

Herpes Simplex Virus

Recurrent herpes simplex virus (HSV) infections are one of the most common complications of HIV infection (see Chapter 48).26,27 Most lesions are caused by HSV-1, although a few are caused by HSV-2. Oral mucosal involvement usually presents on keratinized mucosa. The lesions begin as an area of necrotic epithelium, then spread laterally to form a zone of erosion with a circinate, raised, yellow border. Multiple smaller lesions may coalesce forming an irregular pattern. Intraoral lesions usually appear in conjunction with herpes labialis.

A presumptive diagnosis of HSV infection can be made by clinical appearance (Fig. 65-4A,B). Viral culture can be performed if the diagnosis is in question, or if susceptibility testing is needed due to poor response to therapy. Biopsy or cytology is almost never necessary for the evaluation of herpetic lesions, although occasionally atypical lesions require biopsy.

Figure 65-4 Herpes simplex virus on gingiva (A) and palate (B).

Reprinted from the International AIDS Society-USA, from Reznik DA. Oral manifestations of HIV disease. TOP HIV Med 13:143, 2005.

Therapy

Patients with low CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts and frequent recurrences may develop acyclovir-resistant herpetic lesions (see Chapter 48). There is no effective oral regimen for such lesions. Depending on the mutation causing resistance, either intravenous cidofovir or intravenous foscarnet should be used. Interestingly, when such lesions recur, the isolate may be acyclovir-sensitive.

Epstein–Barr Virus

Oral hairy leukoplakia (OHL) is an Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)-associated lesion. OHL has been clearly linked to HIV disease progression.29–32 OHL also been documented in patients with types of immunosuppression other than HIV infection.33 Although the prevalence of OHL in the HIV-positive population has decreased dramatically with the widespread use of combination antiretroviral therapy (ART), it is still seen in ∼12% of patients.34

Diagnosis is established by clinical appearance (Fig. 65-5). OHL occurs most often on the lateral borders of the tongue, but can extend to the dorsal surface as well as other mucosal surfaces. The lesions range in appearance from faint white vertical streaks to thickened corrugated areas of leukoplakia, with a shaggy, or ‘hairy’, keratotic surface. These white plaques will not rub off helping to differentiate this clinical presentation from pseudomembranous candidiasis.

Figure 65-5 Oral hairy leukoplakia on lateral border of tongue.

Reprinted from the International AIDS Society-USA, from Reznik DA. Oral manifestations of HIV disease. TOP HIV Med 13:143, 2005.

Cytomegalovirus

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) disease can present as painful, nonhealing mucosal ulcerations.35,36 The ulcers may appear anywhere in the oral cavity, with the gingiva, buccal mucosa, and palate being the most common sites. Oral ulcers that are nonresponsive to therapy should be biopsied, with histological verification, for a definitive diagnosis. If oral CMV lesions are documented, other sites of CMV disease such as the retina, should be sought. These oral lesions can be treated with oral valganciclovir or intravenous ganciclovir.

Varicella-Zoster Virus

Varicella-zoster virus can present with painful vesicles along the path of any of the branches of the trigeminal nerve, hence impacting the face and oral mucosa.37,38 Diagnosis requires clinical suspicion and culture or biopsy.

Human Papillomavirus

The incidence of oral warts due to human papillomavirus (HPV) has dramatically increased in the HAART era. Certain “high-risk” types of HPV, such as HPV 16, 18, and 33, have been shown to be associated with the development of invasive oral carcinomas.41–46 The potential for malignant transformation correlates with the presence of HPV DNA, the extent of the disease, and the degree of immunosuppression. Patients with a CD4+ T-lymphocyte count <200 cells/μL are at greatest risk.47 HPV-associated oral lesions present as oral papillomas, condylomata, and focal epithelial hyperplasia. The lesions are usually multiple and may appear on any mucosal surface, most commonly the labial (Fig. 65-6A) and buccal mucosa (Fig. 65-6B), tongue, and gingiva. The vermilion border and labial commissures may also be involved. Lesions may be white, slightly erythematous, or normal in color. Clinical presentations vary from a pedunculated, exophytic lesion with numerous finger-like surface projections (papilloma), to multiple inconspicuous flat-topped papules or papillary areas (focal epithelial hyperplasia). Condylomata present as sessile, pink, exophytic masses with short, blunted surface projections. They are usually larger than papillomas and are typically multiple and clustered. Biopsy may be necessary to establish a diagnosis since the clinical appearance of some HPV-associated lesions may be nonspecific. Treatment should be directed at the removal of the associated lesions by electrosurgery, cryotherapy, or scalpel excision. The recurrence rate is high, and repeated treatment is often necessary.

BACTERIAL INFECTIONS

Gingivitis and Periodontitis

There does not appear to be an increased incidence of conventional periodontal disease in patients with HIV infection.48 Recent studies indicate there is no association between periodontal pocket depth or attachment loss (markers for periodontal disease) and CD4+ T-lymphocyte count.51,52,57 However, severe forms of gingivitis and periodontitis can be seen in HIV-seropositive patients, especially those who are severely immunosuppressed.49

One manifestation of severe gingival disease is linear gingival erythema (LGE; Fig. 65-7). This presents as a distinctive linear band of erythema at the free gingival margin, extending 2–3 mm apically.54 Petechial patches may be seen on the attached gingiva and adjacent alveolar mucosa. Mild pain and occasional bleeding have been reported but are not necessarily characteristic. LGE can be distinguished from conventional gingivitis by its failure to respond to routine plaque control measures and proper home care maintenance. Treatment of LGE should consist of a professional dental prophylaxis with thorough irrigation using a 0.12% chlorhexidine gluconate suspension or a 10% povidone-iodine solution, followed by 0.12% chlorhexidine gluconate rinse twice daily for 2 weeks. Frequent follow-ups and a maintenance dose of 0.12% chlorhexidine gluconate may be required.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree