Chapter 12

Oophorectomy and Other Risk-Reducing Gynecologic Surgeries

IF YOU DEVELOP OVARIAN CANCER, your treatment will involve oophorectomy, surgery to remove your ovaries. If you have a BRCA mutation, the most effective way to lower your high risk for ovarian cancer is prophylactic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO), removal of both ovaries and both fallopian tubes. (It’s important to remove the fallopian tubes as well, because hereditary cancer may develop there.) Several studies of BRCA women, including the Prevention and Observation of Surgical Endpoints (PROSE) research funded by the National Institutes of Health, validate the significant risk-reducing effectiveness of BSO.1 Experts recommend the surgery for women with BRCA mutations, ideally between the ages of 35 and 40 and when they have completed childbearing.

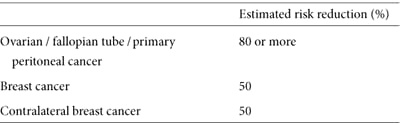

In women with BRCA mutations, BSO reduces the odds of dying from both breast and ovarian cancer, and decreases overall risk for dying prematurely. BSO also cuts your breast cancer risk in half.2 If you develop breast cancer, it reduces your odds for a second diagnosis by half as well.3 (See table 12.)

It may seem logical that removing the ovaries and tubes would reduce all risk for ovarian and fallopian tube cancer, but the facts are a bit more complicated. After BSO, 2 to 6 percent lifetime risk remains—much less than your lifetime risk if you keep your ovaries—for developing primary peritoneal cancer, a disease that begins in the lining, or peritoneum, of the abdomen.4 The peritoneum cannot be removed during oophorectomy, and there’s no proven method of preventing or screening for this rare cancer, which behaves like and is treated like stage 3 or 4 ovarian cancer.

Table 12. Risk reduction from BSO before natural menopause

BSO is not without side effects. It forever ends menstrual periods, which you may welcome, although it also ends fertility. If you don’t plan to have children or you’re already menopausal, oophorectomy might be an easy decision. It’s not as straightforward if you want to pursue prophylactic BSO and also want to become pregnant. A fertility expert can explain your options, and your doctor can help you understand and manage your risk in the meantime. BSO also causes menopause. After surgery, medical intervention may be required to deal with mild to serious hot flashes, dry skin, vaginal dryness, and other symptoms. These symptoms (discussed in chapter 13) are less likely to occur in women who have BSO after natural menopause.

Oophorectomy Procedures

A surgeon needs clear access to the abdominal cavity to inspect the organs for cancer or other abnormalities before she removes the ovaries. She uses either of two techniques.

Laparoscopic BSO is frequently used to remove ovaries and tubes when cancer is not suspected. A tiny fiberoptic camera inserted through a small incision in the navel allows the surgeon to view the abdominal and pelvic areas on a video monitor. She makes two or three additional small incisions, through which she dissects and removes the ovaries. No sutures are required; only a small bandage covers the laparoscopic incision. The resulting scar is miniscule and eventually becomes almost invisible. Recovery after the one- to two-hour procedure may include an overnight hospital stay; some women go home the same day. Pain is controlled with medication during the first couple of weeks after surgery. Most women experience fatigue and need frequent rest throughout the day, recovering fully in one to two weeks.

Laparotomy, or abdominal oophorectomy, is performed when more access is needed to better view the abdomen. This might occur if you have scar tissue from previous surgeries, if your organs appear abnormal, or if the surgeon suspects cancer. In some cases, a laparoscopic oophorectomy ends up as a laparotomy if a larger incision is needed to control bleeding or a complication occurs. During laparotomy, a surgeon makes a four- to six-inch abdominal incision, cutting through the skin, fascia (connective tissue), and peritoneum. She cuts horizontally across the pubic hair line or vertically from the belly button down to the pubic bone. Although a horizontal scar is less noticeable, a vertical incision provides greater visibility into the abdomen and is always used when cancer is suspected. The surgeon pulls the abdominal muscles apart, inspects the organs, and removes the ovaries and fallopian tubes. When completed, she stitches the abdominal layers in reverse order and closes the incision with sutures or staples. A drain may be placed to collect excess fluid. Laparotomy takes about the same time as laparoscopy. Complications are more likely, and recovery is usually longer and more painful. Patients are discharged in two to five days. Abdominal discomfort and fatigue gradually subside after two weeks. Most exercise and lifting must wait until full recovery, usually in four to six weeks.

Either procedure should include an abdominal wash. This involves flushing sterile liquid into the pelvic cavity, removing the fluid, and sending it to a pathologist who looks for any evidence of cancer. If you’re at high risk, a serial sectioning of your ovaries and tubes is critically important.5 This is a close pathological examination of several thin cross-sections of the fallopian tubes and ovaries to be certain no cancer is present. In some BRCA women, pathology reveals a small previously undetected cancer that requires chemotherapy and/or radiation treatment to prevent it from spreading.

Laparotomy (left) and laparoscopic (right) oophorectomy incisions

Even though a gynecologist is trained to perform oophorectomy, it may be to your advantage to have your procedure done by a gynecologic oncologist, a specialist with advanced training who can also recognize and stage gynecologic cancers. If a gynecologist performs your oophorectomy and cancer is found, a second surgery may be needed to stage and determine the extent of the disease. Gynecologic oncologists, however, are familiar with the specific protocol for high-risk women, which includes exploring the pelvic organs for abnormalities or evidence of cancer, performing a peritoneal wash, and completely removing the ovaries and fallopian tubes. If cancer is found, she can remove lymph nodes and as much of the tumor as possible, and then treat you. The Society of Gynecologic Oncologists (www.sgo.org) will help you find a gynecologic oncologist.

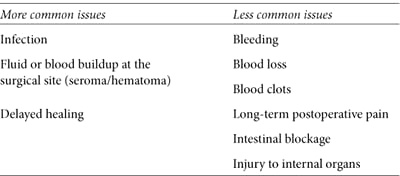

Performed under general anesthesia in a hospital, BSO is a relatively safe operation, but it’s still major surgery, and problems can occur (see table 13).

Table 13. Risks of gynecologic surgery

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree