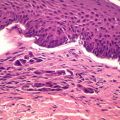

Figure 2.1

Large lateral nasal defect

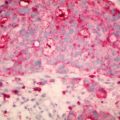

The skin graft was ‘quilted’ in place with a quilting suture through the base of the wound (Fig. 2.2). This method allows me to avoid using a bolus or ‘tie-over’ dressing and therefore use a thin hydrocolloid or foam dressing post operatively. One of the concerns when laying grafts on perichondrium is that graft take can be reduced by accumulation of fluid – seroma or haematoma, and it is important to try and reduce this risk. Tissue sealants or platelet gel and quilting sutures potentially provide an additional intra-operative modality for prevention of fluid accumulation. The mechanism is their ability to act as a hemostatic agent tissue sealant and improve wound healing [4]. When it comes to the nose and full thickness grafts, I have particularly found the quilting suture useful, both to reduce risk of fluid accumulation and to avoid using a bulky dressing post-operatively.

Figure 2.2

Skin graft sutured and quilted in place

The initial graft dressing was done at 5 days post-operatively. After the surgery, the sutured graft was covered with a foam dressing (Allevyn, Smith & Nephew, Christchurch, NZ) and following that with a thin hydrocolloid dressing (DuoDERM® Extra Thin Dressing, ConvaTec, Australia) to make it inconspicuous.

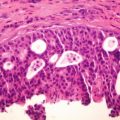

The graft was fully healed at 3 weeks and did not leave any residual deformity, either contour or color mismatch. The image shown at 2 weeks post operatively shows some small suture granulomata on a well-healed graft (Fig. 2.3) due to my use of a continuous fast-absorbing braided suture (VICRYL RAPIDE™ (polyglactin 910) suture, Ethicon)

Figure 2.3

Postoperative appearance at 2 weeks

Discussion

Skin grafts have been known in surgery from circa 2500 BC, when Indian surgeons used them to reconstruct noses [5]. It was during this period the forehead ‘Indian’ flap was also developed to repair amputated noses (sadly, amputation was punishment for alleged adultery for women, and is still reportedly used as punishment in parts of the world such as Afghanistan). In 1875, Wolfe described the full-thickness skin graft that forms the basis for the technique described in this paper [6]. (As an aside, Wolfe was an interesting character, who threw himself into the war for unification of Italy along with Garibaldi [7]. After the war, he returned to his career as an ophthalmologist. Wolfe actually first described the full thickness skin graft as a method to correct ectropion of the eyelids).

Skin grafts have often been considered a less than ideal solution for closure of nasal defects due to the color mismatch they may cause. On the other hand, several plastic surgeons routinely use full-thickness skin grafts for large nasal tip defects. In my view, skin grafts are an excellent option when it comes to the lateral aspect of the nose, but not a good option for anterior surfaces of the nose such as the nasal tip or dorsum – because the color mismatch is more likely to become noticeable. On the lateral aspects of the nose, because light casts a shadow, minor alterations in color are often not noticeable.

It is good to review some general principles of reconstruction of the nose here, especially to do with full thickness skin grafting and also offer some useful tips and techniques.

It is more accepted that allowing for proper client and donor-site selection, a full-thickness skin graft can play an important role in reconstruction of lower third nasal defects, which were previously felt to be off-limits to skin grafts [8]. Unlike flaps which seem to be preferred to skin grafts (to avoid a color mismatch), a skin graft must recruit blood supply from the surrounding tissues at the recipient site. The stages in this process are well known: plasmatic imbibition, inosculation and the bridging phenomenon [9]. The bridging phenomenon is of particular use when laying grafts on relatively avascular sites like the cartilage of the nose. As long as a portion of the defect is well vascularized, a skin graft can recruit vessels from this area to supply blood vessels to the graft overlying the avascular recipient site [10].

I generally perform the procedure under local anesthesia. Contact between the graft dermis and the recipient bed is critical for inosculation – however, I do not aggressively de-fat the graft – it is gently de-fatted using scissors and not by scraping, as in my view that can damage valuable dermal blood vessels. The donor site selection is critical, especially to match ‘like with like,’ as thickness of skin on the nose varies. The skin of the lower third is thick and composed of sebaceous glands, unlike the thin skin of the upper two-thirds of the nose [11]. While some authors do not prefer fenestration of the graft, I tend to make slits that not only allow fluid or blood to escape, but also to allow for easier quilting of the graft via those fenestrations. If the lesion extends to the alar rim, then it is not suitable for a full thickness graft as the ‘alar notching’ this causes can be unsightly. Suitable donor-sites are pre-auricular, post-auricular, glabellar and naso-labial region skin. Some authors specifically use non-absorbable sutures [12]. Some authors suggest that systemic antibiotics with an appropriate bacterial spectrum should be advised in full thickness skin graft reconstruction after surgery for non-melanoma skin cancer of the nose [13]. In my experience of performing skin grafts on the lateral aspect of the nose routinely for large nasal defects, I have not found empirical use of antibiotics has added any value. I also prefer to use absorbable sutures so that there is no need for suture removal and keeping the graft moist with dressings or ointment speeds up the resolution of the sutures.

As mentioned earlier, I do not aggressively de-fat the skin graft. In fact, in deeper defects, which may cause a contour defect and leave a ‘pit’, I find retaining the fat useful. This concept of skin-fat grafting of the nose and its usefulness has also been commented on by other teams [14]. If anything this makes skin grafting of the nose easy and more versatile.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree