CHAPTER 9 Nutrition and the Hard Tissues

By the end of this chapter you should be able to:

• understand the dynamic nature of skeletal metabolism

• define osteomalacia, rickets and osteoporosis

• discuss the role of vitamin D and calcium nutrition in skeletal health

• appreciate the role of other nutrients in skeletal health

• give definitions for dental caries, erosion, abrasion and periodontal disease

• describe the indices used for the measurement of dental caries

• describe the epidemiology and trends of dental caries in Western and other countries

• outline the structure of the tooth

• explain the mechanisms of the decay process

• summarize evidence for the role of dietary sugars and fluoride in the causation and prevention of decay

• compare the relative cariogenicity of various sugars and other carbohydrates

• summarize the interaction of protective effects of fluoride and destructive effects of sugars

9.1 INTRODUCTION

This chapter concerns the physiology and nutritional factors affecting the hard tissues of the body. The first section deals with bones and their two main nutrition related disorders, osteoporosis, and osteomalacia or rickets, and the second section with teeth and their main diet related disorder, dental caries.

9.2 BONE STRUCTURE AND CHANGES

Bone changes

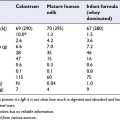

The fetal skeleton is initially composed mainly of unmineralized cartilage, and mineralization occurs mainly during the last 10 weeks of pregnancy at a rate of more than 100 mg calcium/day. This continues after birth as the size and shape of bones changes during growth. Skeletal mass increases from about 100 g in the neonate to about 3000 g in an adult (peak bone mass) at about age 35. Over 90% of peak bone mass is achieved by age 18, and so children and adolescents are a particularly important target for interventions to increase bone mass for later life. Bone mineral content declines in the elderly, and is particularly rapid in women after the menopause, caused in large part by a reduced ovarian production of oestradiol. Peak bone mass is the most important predictor of bone mineral content in later life.

9.4 OSTEOPOROSIS, OSTEOMALACIA AND RICKETS

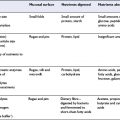

Osteoporosis

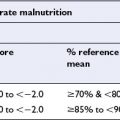

Osteoporosis is characterized by low bone mass and ‘microarchitectural’ deterioration of bone, resulting in an increased risk of fracture. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines osteoporosis as a bone mineral density value less than 2.5 standard deviations below that expected for young adults, and osteopenia when bone mineral density is between 1 and 2.5 standard deviations below the young adult mean. However many osteoporotic fractures occur in individuals who do not fulfil these criteria for a diagnosis of osteoporosis.

Rickets

In the early part of the 20th century it was discovered that rickets could be cured by a fat-soluble nutrient or sunshine exposure. An unfortified infant diet contains a very small amount of vitamin D, although there are small amounts in milk and egg yolk. Causes of osteomalacia and rickets include high dietary intakes of phytate; increased skin pigmentation or traditional dress; calcium deficiency; genetic or acquired disorders of phosphate metabolism or vitamin D metabolism; and deficiency of the enzyme alkaline phosphatase (Box 9.1).

9.5 THE ROLE OF CALCIUM AND VITAMIN D IN BONE (SEE CHAPTER 5)

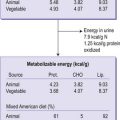

Calcium supplementation and adequate protein intake has important therapeutic value in osteoporosis and combined supplements of calcium and vitamin D are often recommended to patients with osteoporosis. Most calcium supplementation studies which have shown a skeletal effect have used intakes of at least 1000 mg per day. Maintenance of body weight is critical, since moderate weight loss and low body weight are associated with loss of bone mass and risk of fracture. However, excessive calcium intake can result in hypercalcaemia, renal insufficiency or renal stones, and impaired absorption of other nutrients such as iron, phosphorus and zinc.