CHAPTER 13 Public Health Nutrition

By the end of this chapter you should be able to:

• justify public interventions in addressing malnutrition, both under- and over-nutrition

• describe the main types of malnutrition worldwide, their prevalence and trends

• appreciate the type of factors involved in their aetiology

• give examples of causes by level – such as immediate, underlying, and root causes

• appreciate the factors involved in developing preventative measures or appropriate intervention to reduce malnutrition

• describe the types of direct and indirect measures to improve nutritional status

• explain the evolution of emphasis in types of policy interventions used over the last half century to reduce malnutrition

• describe the current challenges to food and nutrition security

• define the terms food security, food insecurity, food supply, food demand, hunger, famine, and Green Revolution

• give examples of past scares concerning the adequacy of the world food supply and reasons for their resolution

• compare food supply with population needs

• list the socioeconomic, agro-ecological and health constraints on future food production

• explain how globalization relates to food security

• compare publicly- and privately-funded agricultural research

• explain the potential for biotechnology in achieving food security

13.1 INTRODUCTION TO PUBLIC HEALTH NUTRITION

The first sections of this chapter review briefly the extent and causes of malnutrition and some of the policy and intervention options available for reducing malnutrition. Direct nutrition interventions have a stated objective of improving nutrition, and indirect interventions or policies may affect nutrition status in important ways but do not necessarily have this as their primary goal. Adequate food supply is one of the essential factors in good nutrition. The subsequent sections describe the world food supply and past trends and future projections of the ability for supply to meet the increased demand caused by population growth and increased affluence, as well as the impact of globalization of food trade and of biotechnology on food security.

13.2 INTRODUCTION TO FOOD AND NUTRITION POLICIES AND INTERVENTIONS

• many services relevant for good nutrition such as nutrition education campaigns are not provided by the private sector

• individual decisions may have a high cost for the community, eg a decision not to get immunized leading to the spread of infection

• they can help to ensure accurate information is available about a food product

• they can ensure equity of distribution such as universal salt iodization or the availability of primary health care.

Good nutrition is related to access to and appropriate utilization of available food. Food supply is therefore part of the equation. The second part of the chapter therefore deals with various factors that affect world food supply and the ability of the world to provide enough food for an increasing population.

13.3 EXTENT AND CAUSES OF MALNUTRITION

Descriptions of malnutrition are usefully classified by stage in the lifecycle. Dramatic growth failure most typically occurs between the ages of 12–18 months with a low probability of catch-up growth. The impairments in cognitive function are also largely irreversible. Hence early infant malnutrition has consequences throughout the lifecycle. Malnourished babies become malnourished adolescents and adults who are less able to learn in school and less productive in the labour market. Malnourished female babies are more likely to be malnourished girls and women who give birth to malnourished babies. Moreover the fetal origins hypothesis (see chapter 6) proposes that maternal dietary imbalances at critical periods of development in the womb can trigger adaptations that affect fetal structure and metabolism in ways that predispose the individual to chronic diseases later in life. This section reviews the extent and causes of malnutrition at different stages in the lifecycle.

Assessment of extent and worldwide distribution of malnutrition

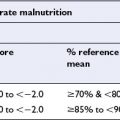

Stunting (low height for age) and underweight (low weight for age) of infants in the developing world is widespread. A third of all children under the age of 5 in developing countries are stunted and underweight. In South Asia almost half are underweight, although nutritional status in all regions of the world except sub-Saharan Africa has been improving over recent decades (Table 13.1)

Table 13.1 Percent of pre-schoolers (under-5s) that have low weight for age

| Region | Percent under-fives underweight | |

|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 2000 | |

| Developing countries | 32 | 28 |

| East Asia/Pacific | 24 | 16 |

| Latin America/Caribbean | 11 | 8 |

| Middle East/North Africa | 13 | 17 |

| South Asia | 55 | 48 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 32 | 31 |

Source: UNICEF 2003 (http://www.childinfo.org/eddb/malnutrition/index.htm; accessed 29 July 2003)

The proportion of adults who fall below the cut-off for underweight (BMI < 17) and above the cut-off point for obesity (BMI ≥ 30) is shown in Table 13.2. The poorest countries are therefore still grappling with underweight and the developed countries with overnutrition issues such as obesity. Despite the widespread efforts to reduce the extent of obesity and its associated diseases, their prevalence continues to increase.

Table 13.2 Percent below and above BMI cut-offs: adults in 2000

| BMI < 17 (underweight) | BMI ≥ 30 (obese) | |

|---|---|---|

| Least developed (n = 45) | 8.9 | 1.8 |

| Developing (78) | 6.9 | 4.8 |

| Transition (27) | 2.4 | 17.1 |

| Developed market (24) | 1.6 | 20.4 |

Source: WHO 2002 (http://www.who.int/nut/db_bmi.htm; accessed 9 September 2002)

Anaemia prevalence is used as a proxy for iron deficiency. In industrialized countries this is likely to be a close approximation, but in the developing world anaemia can occur due to factors other than iron deficiency such as malaria, other parasitic infections, current infectious diseases and other pathologies. Anaemia is a serious problem throughout the lifecycle, both in industrialized and developing countries where the prevalence is over 10% and 14% respectively. It is a particular problem for pregnant women who have high haematinic needs, with a prevalence of almost 20% in industrialized countries and almost 60% in developing countries (see chapters 5 & 8).

One of the most visible manifestations of iodine deficiency is goitre (see chapter 5) and this is used as one indicator of deficiency. The overall world prevalence of goitre is 13%, highest in the African region (20%), followed by Europe (15%), SE Asia (12%), Western Pacific (8%) and the Americas (5%)

Severe vitamin A deficiency (VAD) manifests itself clinically as night blindness and corneal xerosis (see chapter 5). Sub-clinical vitamin A deficiency in pre-school children is defined as serum retinol level <0.7 μmol/L. While clinical signs of vitamin A deficiency are relatively rare (estimated 3 million pre-school children), subclinical deficiency, which increases the likelihood of morbidity and mortality in pre-schoolers, is estimated to be widespread (75–250 million) in developing countries only, and most likely found in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.

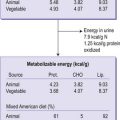

In addition to anthropometric data and patchy micronutrient status data, food balance sheet data are available for most developing countries for most years. These data are compiled by the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) from food production, food trade and food aid flows. The foods are converted into calories and divided by population size to give the dietary energy supply (DES) in calories per capita. The DES numbers are converted to estimates of the percentages of individuals without adequate access to food: 17% in developing countries, with the highest in sub-Saharan Africa (33%), and 7% in countries in transition.

Some of the factors behind the tragic decline in nutrition status in sub-Saharan Africa include: closed markets in the developed world (especially the EU) for their exports; HIV/AIDS generating a health and development crisis and undermining the ability to respond to the crisis; wars and refugee movements; military expenditure; drought; crop and livestock disease; many ecosystems making technology diffusion and adaptation difficult; under-investment in agricultural research; no economy serving as regional driver (Nigeria and South Africa’s under-whelming economic performance); low levels of human capital in terms of literacy; declining terms of trade for natural resources on world markets; low population densities leading to thin infrastructure and market institutions.

Analysis of causes

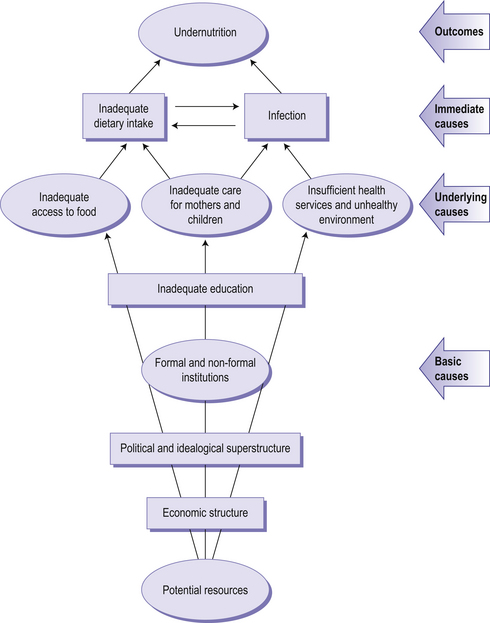

Figure 13.1 summarizes the causes of undernutrition in children, but much of this scheme is also relevant to adults. The causes lie at several levels (immediate, underlying and basic) and in many sectors (agriculture, health, water, education, and employment, etc). It is important to understand the causes of malnutrition to guide the interventions needed to improve nutrition status. The following examples focus first on undernutrition, followed by similar analyses that can be made for the chronic nutrition related diseases (overnutrition).

Immediate causes

The most immediate causes of malnutrition in young children (and also adults) are poor diet and infection (see chapters 6 & 8). If the child is not able to ingest enough food, both in terms of quantity and quality that can be used for growth and development, then malnutrition occurs. Infection and an inadequate diet reinforce each other as infection reduces the intake of nutrients by diminishing appetite, inhibiting nutrient absorption, and increasing nutrient requirements for combating infection while poor diet reduces the effectiveness of the immune function.

Basic causes

The basic or root causes of malnutrition are essentially political and economic. There are very few instances of high levels of undernutrition (as opposed to overnutrition) above a certain GDP per capita. A 10% increase in income produces a 5% reduction in the rate of undernutrition but income growth is by no means sufficient, and there is a wide range of levels of undernutrition at a given income level. Other factors beyond income growth are obviously essential for good nutrition, such as good levels of education, social equity, and enlightened government behaviour. Good governance – by which we mean institutions that give voice to all parts of society; respect for the civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights of its citizens; and appropriate levels of investment in public goods such as safety, research, roads, health and education – is more likely to produce these conditions. Good education levels mean that individuals know how to access, assess, and use information that is helpful to the attainment of good nutrition status (such as the right types of foods to consume, what to do in the case of diarrhoea, and the optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding). The status of women relative to men is a dimension of society and values that is crucial to the nutrition status of women and of infants.

• Undernutrition is located largely in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa; it is declining slowly in South Asia, but not in sub-Saharan Africa

• Overnutrition is present in all countries, in general is more prevalent in developed countries, but is increasing most rapidly in the developing world

• Sub-Saharan Africa is beset by multiple factors at all levels that make progress in reducing malnutrition very difficult

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree