Introduction

Nutrition care is essential not only in after care or survivorship but also as a supportive resource throughout diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer. Patients often request nutrition advice early on in their care. Breast cancer patients in particular show interest in learning more about diet and lifestyle. Many want to learn all they can to ensure a good outcome. In our system, we focus on plant-based eating, as able, and promote physical activity as tolerated. When patients begin treatment, our first goal is for them to survive and thrive throughout treatment. We assist with symptom management throughout treatment, in addition to providing healthy eating and lifestyle information.

Role of Oncology Dietitians

Oncology dietitians have a specific focus on oncology patients and are encouraged to obtain designated certification. The Oncology Nutrition Dietetic Practice Group of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics has worked together with the Commission on Dietetic Registration to create a Board Certification credential (Certified Specialist in Oncology Nutrition [CSO]) for Registered Dietitians in Oncology Nutrition. CSO stands for Board Certified Specialist in Oncology Nutrition. A recommended minimum of 2 years of clinical practice with documentation of 2000 hours of practice experience in the oncology care setting is required.

Oncology dietitians participate in multidisciplinary clinics where appropriate, including breast, head and neck, gastrointestinal, thoracic cancers, and survivorship. Oncology dietitians provide education to patients, family, and staff. We also present to the community for various events and participate in community health fairs regarding cancer prevention.

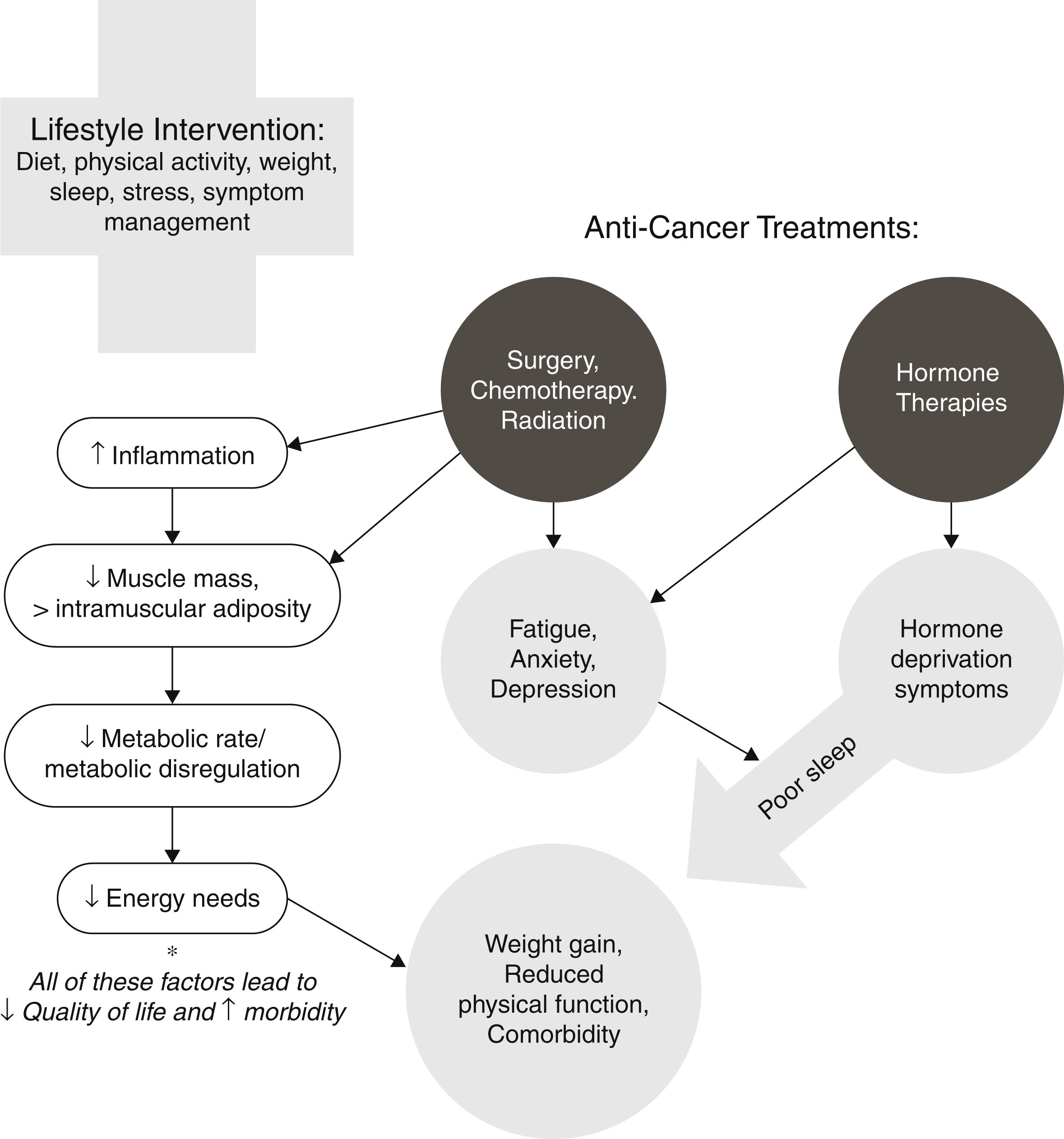

Oncology dietitians assess for malnutrition, as this is a common issue in the oncology population. We perform a Nutrition Focused Physical Assessment on our patients. We document this assessment in the electronic medical record (EMR) and update it throughout treatment. Preventing malnutrition and early intervention is always preferable and far more achievable than reversing severe malnutrition. Documenting malnutrition in the outpatient setting helps support the acute care staff with malnutrition diagnoses in the hospital setting. Outcomes are affected by malnutrition status, so documenting this throughout a patient’s care supports accuracy and efficacy, in addition to achieving best outcomes ( Fig. 12.1 ).

During treatment, oncology dietitians support patients with food and fluid recommendations. We may suggest oral nutrition supplement drinks. Often patients are interested in making healthy changes during treatment, but other times their focus is survival or getting through treatment. It is imperative that the oncology dietitian meets the patient where they are with their own treatment goals.

Oncology dietitians support our colleagues’ recommendations to start a walking program as soon as possible. We promote physical activity as able, and often suggest cancer rehabilitation for patients when appropriate. If patients are reluctant to try cancer rehab or therapies, additional encouragement from the dietitian to try these may be beneficial.

Certain patients may need nutrition support, such as enteral or parenteral nutrition. The oncology dietitian assesses the patient’s needs and collaborates with the provider to prescribe the appropriate enteral or parenteral formula. Some oncology dietitians instruct patients on how to use their feeding tubes when needed. We monitor their intake and tolerance for nutrition support and ensure proper fluid intake.

Medical Nutrition Therapy

Medical nutrition therapy (MNT) is defined as “nutritional diagnostic, therapy, and counseling services for the purpose of disease management which are furnished by a registered dietitian or nutrition professional” (Medicare MNT legislation, effective January 1, 2022). MNT is a specific application of the Nutrition Care Process in clinical settings that is focused on the management of diseases. MNT involves in-depth individualized nutrition assessment and a duration and frequency of care using the Nutrition Care Process to manage disease.

MNT for oncology patients includes setting goals of care. These include addressing any nutrition impact symptoms resulting from the disease and its treatment; supporting the patient’s goals while providing evidenced-based care; limiting unintentional weight loss during treatment to less than 1 to 2 pounds per week; and encouraging the patient to maintain and obtain a healthy body weight. Previous recommendations in oncology patients would have avoided any weight loss during treatment, even intentional, to improve other health outcomes and minimize additional cancer risk. More recent evidence in the overweight patient suggests slow, intentional weight loss while eating healthfully and increasing physical activity is considered safe. A study comparing women with breast cancer and women without breast cancer found no difference in resting energy expenditure between the two groups.

Nutrition-related problems during breast cancer treatment include fatigue, vasomotor symptoms, lymphedema, bone loss, musculoskeletal symptoms from aromatase inhibitors, neuropathy, nausea and vomiting from chemotherapy, mucositis, taste changes, and weight gain.

A common issue for cancer patients, particularly breast cancer, is well-meaning family and friends providing their own suggestions for diet and supplementation. With information so easily accessible, this can oftentimes prove to be more of a hinderance than helpful. People are overloaded with information and may find it difficult to sift through facts or solutions that are effective. Food and supplement pills are two areas where patients get excessive information or suggestions. We can help them navigate this complicated part of their treatment with reliable, reputable resources.

Family members often would like to be able to do something to help their loved one who is suffering through a diagnosis and treatment. Food is an area they often feel they can help with. Part of our role as a dietitian is to help family members understand the complexity of symptoms, as well as gray areas. Things can change quickly in symptoms and side effects—something that worked last week, or last cycle, may not work today, or at this time. We can help patients and family members understand this changing flow, and realize it is to be expected and common. Family members work hard to prepare foods for their loved one that they request, usually like, and typically work well, but often the patient is unable to eat it as desired or finish a plate of food. As frustrating as this is to deal with, it is quite common. Sometimes reassuring patients and families that this experience is fairly common is a way to help them cope with this aspect of their disease. Sometimes a husband or a wife will feel this inability to eat or finish a plate of food is personal to the helper. It is important we remind them this is a normal challenge facing patients on cancer treatment.

Many nutrition supplement pills make claims they can speed up apoptosis, slow tumor growth, or prevent cancer altogether. As nutrition professionals we must help our patients and family members sift through this information as well. Some supplement pills may interact with certain chemotherapy or immunotherapy drugs, causing them to become less efficacious. Many of these pills are metabolized on the same pathway as the antineoplastic drugs, thus potentially interfering with the drugs’ effectiveness. Oncology dietitians can recommend food sources of vitamins and minerals to help manage side effects, and potentially increase effectiveness of these therapies. These changes should be made in consultation with the patient’s treating oncologist.

Evidence shows a diet made up mostly of minimally processed plants can lower the risk for cancer, in addition to other chronic diseases. Getting the health benefits of plant-based diet eating does not require one to completely remove all animal proteins (eggs, poultry, fish, and dairy) from one’s diet. Instead, one should make plants the majority of each meal. Decreasing consumption of red meat can decrease the risk of breast cancer. Including omega-3 fatty acids in the diet has been shown to decrease mortality in breast cancer patients.

Phytonutrients are an important part of a plant-based diet. They provide color, flavor, fiber, and texture. Phytonutrients include carotenoids, lycopene, isoflavones, and anthocyanins. They may help prevent cancer through a variety of mechanisms, including preventing damage to cellular DNA. Different colors of plant-based foods provide different combinations of phytonutrients. The type and amounts of phytonutrients vary greatly between vegetables and fruits. We recommend including a wide variety of colorful plant foods to get the benefits from as many different phytonutrients as possible.

Functional foods are foods that are eaten in the diet to provide beneficial properties that go beyond the basic nutritional function. In relation to breast cancer, soy and flaxseed have been studied for the effects they can have on breast cancer risks and the effects their compounds have on tumors.

Soy

It is important to address the link between soy consumption and breast cancer risk. Many breast cancer patients feel that they need to avoid soy. Soy’s role has been controversial because earlier animal studies suggested that the phytoestrogens contained in soy isoflavones may stimulate breast cancer growth. Newer studies have found that this is not the case and, in some cases, those phytoestrogens may lower the risk of breast cancer. These studies have found that it is safe to use soy in moderation in breast cancer patients. Some lab studies have shown that isoflavones could act like estrogen and promote tumor growth, and other studies found them to act against the effects of estrogen and have protective properties. Meta-analysis of the prospective cohort studies had previously shown that relationships between levels of dietary isoflavones and breast cancer risk was inconclusive, but newer meta-analysis explored all possible correlations between dietary isoflavone intake and the risk of breast cancer. This analysis found that moderate intake of soy foods was not significantly related to breast cancer risk, but a high intake of soy foods correlated with reduced risk of breast cancer (RR = 0.87, P = .048). In this meta-analysis, it also found that isoflavones may inhibit aromatase synthesis by binding to the estrogen receptor (ER), possibly blocking the binding of more potent natural estrogens. The Zhao et al. meta-analysis found that high intakes of soy foods provide a beneficial role in reducing the risk of breast cancer but did not study the mechanisms of how soy compounds do this.

While soy is not particularly common in the North American and European diets, it is a common protein in diets of Asian countries. Based on observational studies, soy food consumption may provide protection from breast cancer primarily in Asian countries but not Western countries. It raises the question of the protective effects of soy foods based on genetic factors such as metabolic enzymes, timing of exposure, or intestinal metabolism by microbiota. In Asian countries, soy is introduced into the diet at a young age, and it is hypothesized that consumption during the prepubescent period can affect breast tissue morphology, decreasing overall risk of developing breast cancer. Asian populations have the highest intake of isoflavones in the diet with 20 to 50 mg/day. In Western countries, it is less common to eat whole soy foods, and it is usually introduced later in the life span, with North American populations consuming between 0.15 and 3 mg/day and European populations consuming even less at 0.49 to 1 mg. The occurrence of breast cancer in the United States and Europe is two to four times higher than in Asia. There have been many randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to study how introducing soy isoflavones into the diet can affect estrogen homeostasis and its effect on breast cancer risk.

With the promotion of plant-based diets, soy is an important protein because it has the complete amino acid profile that the body requires, making it an ideal substitute for animal proteins. It is also lower in calorie and fat content than some animal proteins, which can be helpful in weight management. Besides being a good source of protein, many soy foods are good sources of fiber and selenium. Soy isoflavones are also good source of antioxidants.

Soy contains six different isoflavones with the three primaries being daidzein, genistein, and glycitein. Isoflavones are phytoestrogens, and soy is the main source of phytoestrogens in the human diet. They are structurally like 17-β-estradiol and may bind to estrogen Erα and Erβ receptors. Genistein, the main isoflavone in soy, was shown to have a two-phase effect on the ER present on breast cancer cells in a study by researchers at Texas A&M University-Commerce. At low concentrations, genistein stimulated the growth of positive-ER breast cancer cells, whereas at higher concentrations it inhibited the growth of ER positive breast cancer cells.

Soy is considered a healthy food due to its many health-promoting compounds. Isoflavones exert antioxidant properties that protect breast cells from the damage of oxidative stress that can lead to cancer development through stimulation of inflammatory and proliferative pathways. Other compounds such as phenolic acid, phytic acid, lignans, and saponins can provide more antioxidant and anti-inflammatory defense against cancer proliferation. Soy is also a good source of folate helping maintain healthy deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and keep cancer-promoting genes inactivated. Half a cup of cooked soybeans contains 47 µg of folate while a quarter cup of soynuts contain almost half the daily recommended value of folate.

Soy is considered safe to consume in moderation for breast cancer patients and survivors, including those with estrogen-sensitive breast cancers. Moderate consumption is one to two standard servings of whole soy foods. This is less than the average intake in Asian countries of up to three servings of soy foods that contribute up to 100 mg of isoflavones per day with no increased risk of breast cancer. Whole soy foods are tofu, soy milk, edamame, or soy nuts. Each serving averages about 7 g of protein and 25 mg of isoflavones.

Flaxseed

Flaxseed has also been extensively studied in relation to breast cancer. It is important to understand flaxseed and how to incorporate it into the diet before, during, and after treatment. It can be consumed as whole seed, ground seed, flaxseed oil, or as partially defatted flax meal. There are two species of flaxseed; golden flaxseed grown in colder climates; and brown flaxseed grown in warmer, humid climates. There are four main bioactive compounds in flaxseed: alpha-linoleic acid (ALA), an omega-3 fatty acid, lignans, and fiber. Flaxseed is also a good source of magnesium, phosphorous, manganese, vitamin B1, selenium, and zinc.

In both animal studies and human trials, dietary flaxseed has been proven protective against breast cancer. Flax is the richest source of lignans, containing 100 times more than any other food. These phytoestrogens can modify estrogen levels through estrogenic and anti-estrogenic effects due to rich compositions of ALA and secoisolariciresinol diglucoside (SDG), which makes up about 95% of flaxseed lignan content. Doses of 50 mg SDG have been shown to reduce tumors through the action of bacteria in the colon converting the SDG into enterolignans, enterolactone, and enterodiol, which bind to the estrogen receptors and affect tumor cell growth. These metabolites are structurally like estrogen and have a weak estrogenic effect. SDG can reduce cancer mortality by 33% to 70%.

Omega-3 fatty acids are important to the diet, as they are an essential fatty acid that the body cannot make on its own. Flaxseed is considered the best plant-based source of omega-3 fatty acids in the diet. The Western diet lacks in omega-3 fatty acids due to the extensive processing of foods and other agricultural practices. The recommendation for the ratio of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) in the diet is 1:1 to 2:1 of omega-6 fatty acids to omega-3 fatty acids. As mentioned earlier, the ALA is the omega-3 fatty acid present in flaxseed and is the precursor to eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexanoic acid (DHA). These compounds are anti-inflammatory and can be protective against cancer. The recommendation for daily intake is one to four tablespoons (~13 to 51 g) of ground flaxseed per day, but more human studies are needed. Ground flaxseed is preferable, as it is easier for the body to access the nutrients in ground flaxseed over the whole seed.

There has been concern over interaction of flaxseed when patients are taking Tamoxifen. Per experimental studies, it is safe to consume flaxseed when taking Tamoxifen. Doing so can possibly have a protective effect. Flax has also been studied with other breast cancer therapies and was found to downregulate the cardiotoxicity of Doxorubicin and Trastuzumab in mouse studies. This is likely attributed to the antioxidant effect decreasing reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, but more studies are needed.

Lymphedema

Lymphedema occurs in an estimated 20% to 64% of breast cancer patients. The swelling from obstructed lymphatic vessels in the arm, shoulder, and trunk can be painful and affect a person’s feeling of health and well-being on many levels. It is characterized by a progressive increase in inflammation, depositing of fat, and fibrosis in edematous tissues. One of the major risk factors for breast cancer-related lymphedema (BCRL) after treatment is overweight status and obesity. A meta-analysis found that there is an upward trend in BCRL with increasing body mass index (BMI). In this analysis, the odds ratio (OR) of obese (BMI >30 kg/m²) breast cancer patients to normal weight patients was 1.84, and 1.39 for obese versus overweight (BMI =25 to 29.9 kg/m²). This demonstrates a positive association between weight and the degree of lymphedema.

A 5% to 10% weight loss can have a significant impact on health as well as lymphedema. Studies have shown that weight loss is positively correlated to decreased volume of lymphedema and the impact of lymphedema on quality of life. Currently there is no specific diet for lymphedema, and many diets have been studied including calorie restricted, ketogenic, intermittent fasting, and anti-inflammatory diets. All have had some positive outcomes with weight loss and volume.

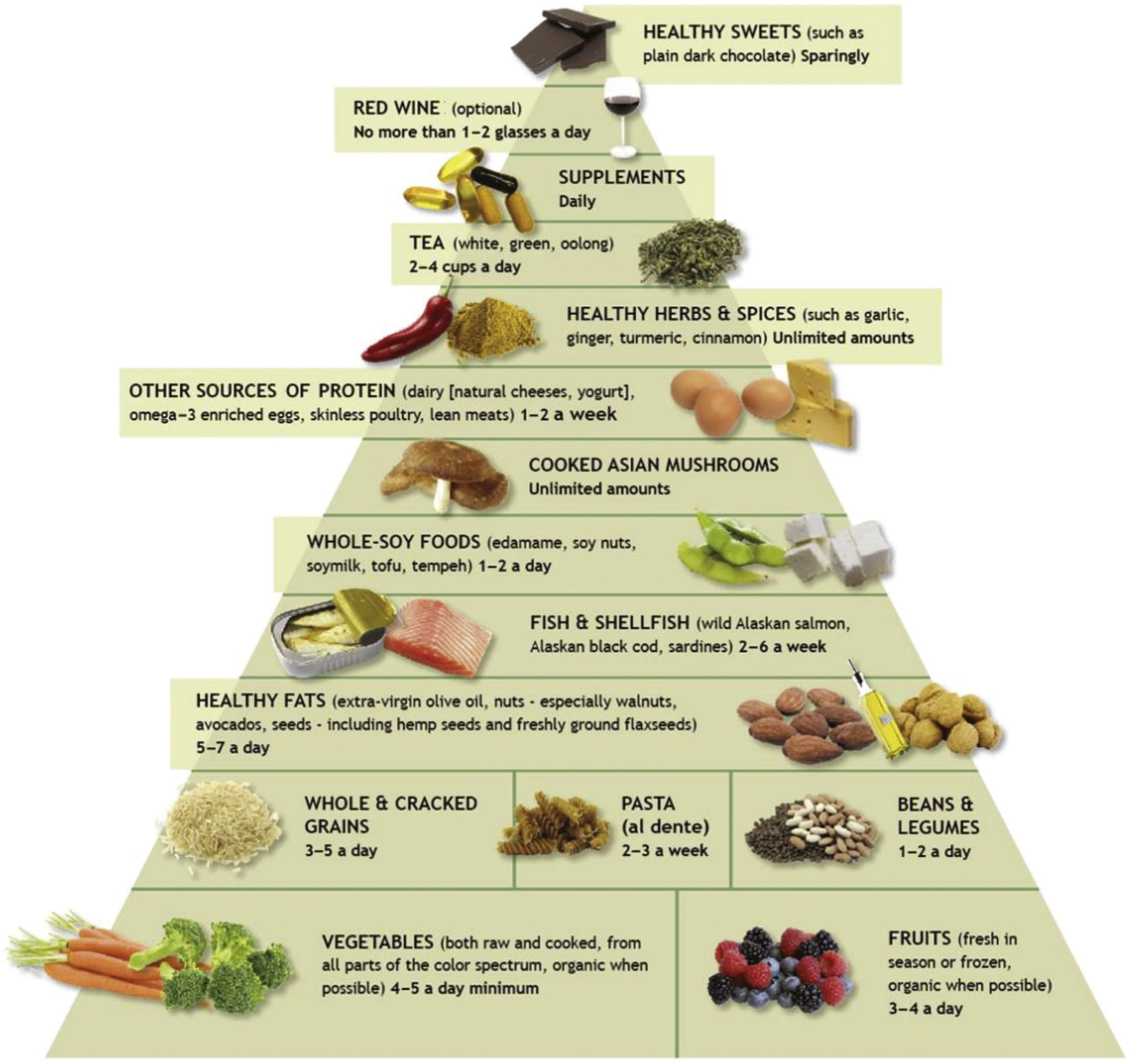

Anti-inflammatory Diet

An anti-inflammatory diet consists of foods that are rich in antioxidants, fiber, phytonutrients, plant-based and lean animal proteins, and anti-inflammatory spices. It can be helpful in managing weight and, in turn, reduce lymphedema. The anti-inflammatory diet also focuses on mindful eating, which focuses on using senses during the eating experience. It also suggests slowing down when eating, taking time with the meal process. Mindful eating can help with weight loss as well as lowering cortisol levels. Anti-inflammatory diets focus on a high variety of vegetables and fruits of a variety of colors. Protein is mostly plant-based but also includes fatty fish and lean animal protein, with little to no dairy. Healthy fats come from avocados, nuts, seeds, and olive oil. Herbs and spices are included for their anti-inflammatory properties, and there is focus on a healthy lifestyle. Many diets have anti-inflammatory properties, and the Mediterranean diet is well known for its anti-inflammatory properties. The Nordic diet and the Okinawa diet also have been studied for their diversity of anti-inflammatory nutrients and health properties. These types of diets fit in with the American Institute of Cancer Research and American Cancer Society dietary recommendations to reduce cancer risk and recurrence ( Fig. 12.2 ).