71.1

Introduction

The general nutritional advice for skeletal health is that adults should follow a varied nutrient-rich diet with adequate protein and fruits and vegetables, and they should also ensure an adequate intake of calcium and vitamin D. These nutrients were covered in the previous chapter along with a discussion of the nutrients that influence their metabolism. Information in the following chapter is further explained in a recent review paper .

In a report from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2000, 52% of adults reported taking a dietary supplement in the past month, with higher rates in individuals with a diagnosis of a chronic disease . Many adults resort to the use of supplements and nutraceuticals for their skeletal health. Nutraceuticals are defined as any substance that is a part of a food that may provide medical or health benefits, including the prevention and treatment of disease. Nutraceuticals are various substances that include isolated nutrients, dietary supplements, herbal products, and medical foods (available only by prescription). The Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (1994), states that the dietary supplement manufacturer is responsible for ensuring the safety of a dietary supplement and that any health claims should not be false or misleading; in fact, there should not be claims that the product prevents or cures disease. Supplement is defined as a product that contains a vitamin, mineral, amino acid, herb, or other botanical or dietary substance that will increase total dietary intake of that ingredient, and there are no provisions in the law for Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to “approve” dietary supplements for safety or effectiveness before they reach the consumer .

71.2

Phytoestrogens

71.2.1

Isoflavones

Phytoestrogens are naturally occurring plant compounds that can function like estrogen agonist–antagonists. Phytoestrogens have three classes: (1) isoflavones (genistein, daidzein, glycitein) found in soybeans and soy products; (2) chickpeas and other legumes, lignans (enterolactone and enterodiol) that are found in oilseeds such as flaxseed, cereal bran, and legumes; and (3) coumestans (coumestrol) that are found in alfalfa and clover. Black cohosh may also have estrogenic activity . Many of these naturally occurring phytoestrogens are purified and concentrated into high-dose dietary supplements.

The typical American diet contains only about 1–3 mg/day of isoflavones, while typical Asian diets have traditionally higher intakes (30–60 mg/day) of isoflavones . The Dietary Guidelines for Americans (2010) has added fortified soy products as a replacement option for dairy or for protein, which may lead to an increased intake of soy products in the United States . Although legumes such as soybeans, green beans, and mung beans have isoflavones, they are present mostly as glycosides that are poorly absorbed on consumption. Processing legumes into miso, natto, soy milk, and tofu improves absorbability. Consuming moderate amounts of traditionally prepared and minimally processed soy foods may offer modest health benefits while minimizing potential for any adverse health effects .

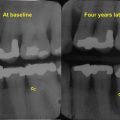

Some bone effects of isoflavones depend on estrogen receptors for mediation, while others are estrogen receptor independent. Isoflavones bind to α and β estrogen receptors and are predominantly agonists, based on transcriptional activation assays . Isoflavones could benefit bone because they have stimulatory effects on osteoblasts and hinder osteoclast and adipocyte generation . Some isoflavones act as potent antioxidants that also could lead to favorable bone balance . Dietary supplements containing genistein-like isoflavones (from soy cotyledon and germ) can modestly suppress net bone resorption in postmenopausal women suggesting another mechanism to improve bone health that appears to be specific to different isoflavones. Mixed isoflavones in their natural proportion were reported to be the most effective isoflavone supplement at improving bone calcium retention, regardless of an individual’s equol-producing status . In a double-blind randomized study, 200 early postmenopausal women were randomized to 15 g soy protein with 66 mg isoflavone (SPI) or 15 g soy protein alone (SP), daily for 6 months. There was a significant reduction in bone resorption (CTX) followed by a significant reduction in type I procollagen- N -propeptide (P1NP) more marked between 3 and 6 months when comparing SPI compared to SP supplementation . In one study the bone-sparing properties of isoflavones were enhanced by maintaining isoflavones in aglycone form through fermentation and by providing probiotics to improve intestinal uptake and isoflavone metabolism . However, the demonstration that these changes result in improved bone density or reduced fractures is limited.

The data suggesting that dietary phytoestrogens lower fracture risk are limited to observational studies and subject to confounding. Women with high dietary soy intake (>13.26 g soy/day) had a 36% lower fracture risk as compared to women with low dietary soy intake (<4.98 g soy/day) in a dose-dependent fashion . In another study of 63,257 Singapore Chinese participants between the ages of 45 and 72, soy intake was unrelated to hip fracture risk in men, but in postmenopausal women, soy protein intake was associated with an approximate 25% reduction in risk .

Several reviews and metaanalyses have concluded that there is either a lack of effect or only a modest effect of soy protein and isolates on the skeleton . The inconsistent skeletal benefit may be a result of differences in study design and duration, sample size, initial bone mineral density (BMD) level, years since menopause, age, body weight, and the baseline intake of soy, calcium, and other nutrients. Results from randomized controlled trials subsequent to these reviews continue to be inconsistent and primarily negative. Studies of between 60 and 400 postmenopausal women have shown either no benefit or only a modest benefit on preventing bone loss . These studies have used soy protein isolates and/or isoflavones of varying doses and compositions for 9 months to 3 years, and in most cases calcium and vitamin D supplements were also given to all study participants. Therefore many well-designed trials have determined that there is limited or no skeletal benefit from soy protein isolates or isoflavones.

Isoflavones, whether evaluated as soy proteins or soy isoflavones, that contain varying amounts of genistein, daidzein, and glycitein, do not appear to provide a consistent skeletal benefit to postmenopausal women . However, 26 Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) ( n =2652) were included in a metaanalysis and when isolating studies that provide isoflavone aglycones in their treatment arm, the average BMD effect was increased at the spine (5 RCTs, n =682) and femoral neck (4 RCTs, n =524) when compared with the control ( P <.05) . The aglycone form of isoflavones may have improved bioavailability and biological efficacy when compared to other isoflavone glycosides , leading to the apparent benefit specific to this compound.

An aglycone form of Isoflavone (genistein) has also been evaluated in combination with other nutrients. In a 6-month double-blind pilot study, 70 subjects were randomized to receive daily either calcium only or a blend which consisted of genistein (30 mg/day), vitamin D3 (800 IU/day), vitamin K1 (150 micrograms/day) and polyunsaturated fatty acids (geniVida TM ). In this study, femoral neck BMD and bone turnover [formation (Bone specific alkaline phosphatase but not osteocalcin) followed by resorption (N-telopeptide)] were higher in the treated than in the control group after 6 months .

Isoflavones, in the aglycone form, have also been marketed as a Medical Food, a designation that requires data to support an indication for treatment (of low bone mass) and also show that all ingredients of the product are generally regarded as safe. One medical food is Fosteum containing 27 mg genistein aglycone, 200 IU vitamin D, and 20 mg citrated zinc bisglycinate (4 mg elemental zinc). In two studies , 54 mg daily of genistein aglycone (the major component of Fosteum) led to gains in BMD at the spine and the hip similar to hormone therapy, compared to bone loss in the placebo group. In a post hoc analysis of a subgroup of patients from this study who had osteoporosis, genistein plus calcium and vitamin D3 treatment demonstrated similar benefits of BMD increase at the femur versus placebo over 2 years . The reported benefits of genistein aglycone, in contrast to several studies with negative outcomes that used other isoflavone compounds, may be related to the specificity of this isoflavone compound, its bioavailability and bone affinity, or the dose used. Furthermore, results showing increased bone mass in women taking genistein aglycone need to be confirmed in a large head to head clinical trial. Some calcium supplements have now added genistein to create a “product to promote bone health” in the words of one manufacturer. The product includes 27 mg genistein, along with other nutrients, and the reference in support of this product is based on the data mentioned earlier .

The safety of isoflavones has been evaluated in several studies. One potential side effect is that some women develop nausea or gastric irritability, stomach pain, vomiting, and constipation when taking some products , but taking isoflavones with food appears to minimize these effects. Safety data have been reported regarding the effect of genistein and other isoflavones on endometrial thickness or vaginal cytology, changes in breast tissue density or breast cancer, with no negative effects in both epidemiologic studies and clinical trials with up to 3 years duration in postmenopausal women .

Data are clearly needed to confirm some of the efficacy findings and to elucidate the differences between the different isoflavones and the apparent benefit with aglycone isoflavone equivalents. The aglycone isoflavone equivalents were reported to be the most bioactive form of isoflavones in an National Institutes of Health (NIH) workshop . Investigations need to be specific with regard to the isoflavone used and analyze the contents of the treatment in rigorously designed clinical trials for a longer duration.

71.2.2

Red clover ( Trifolium pratense )

Red clover is a wild plant belonging to the legume family and is often used in attempts to relieve symptoms of menopause, and treat high cholesterol, and osteoporosis. A review of the potential skeletal benefit of red clover concluded that there was limited evidence of efficacy . In a recent placebo-controlled 3-year trial, 40 mg of red clover produced no effect on BMD in 401 women with a family history of breast cancer . Red clover does seem to be safe for most adults when used for short periods of time and to improve menopausal symptoms . However, it is unknown whether red clover is safe for women who have breast cancer or other hormone-sensitive cancers.

71.2.3

Ipriflavone

Ipriflavone is synthesized from the soy isoflavone, daidzein. In two studies, improvements in bone mass were seen with ipriflavone treatment versus placebo . However, in a 3-year study, ipriflavone was no better than placebo in preventing bone loss and fractures in postmenopausal women . Furthermore, there were concerns with ipriflavone’s side effects such as stomach pain, diarrhea or dizziness, and a potential decreased white blood cell count (lymphocytopenia) .

71.2.4

Black cohosh ( Cimicifuga racemosa )

Black cohosh is an herbal member of the buttercup family that is sold as a dietary supplement. It is available as a tablet, capsule, or liquid, at varying doses from 120 to 540 mg and is made from the roots and underground stems of the buttercup. It is labeled as black cohosh or Cimicifuga racemosa . Black cohosh may have estrogenic activity, and this has led to the belief that it may protect skeletal health . The benefit of black cohosh for treating or preventing osteoporosis is unclear, although black cohosh for 12 weeks increases markers of bone formation in postmenopausal women , but there was no improvement BMD . In addition, a Cochrane review of 16 randomized controlled trials in 2027 perimenopausal or postmenopausal women found that black cohosh at a median daily dose of 40 mg for a mean duration of 23 weeks relieved menopausal symptoms . Of recent concern are case reports of hepatitis as well as liver failure in women who were taking black cohosh . Less serious side effects include headaches, gastric complaints, heaviness in the legs, and weight problems.

71.2.4.1

Summary

There appears to be little benefit of isolated soy protein isoflavones with regard to increasing bone density in postmenopausal women. The metabolism and composition of the phytoestrogen along with the usual intake of soy and other dietary factors has been variable. The variability in skeletal response that does exist may be a result of which isolated soy protein isoflavones are provided. In an NIH workshop in July 2009, it was determined that aglycone isoflavone equivalents are the most bioactive form of isoflavones . Investigations need to be specific with regard to the isoflavone used and analyze the contents of the treatment in rigorously designed clinical trials for a longer duration.

71.3

Dehydroepiandrosterone

Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) is a steroid hormone that serves as a precursor to androgens in men and estrogens in women. Serum levels of DHEA sulfate (DHEA-S) fall with age in both men and women. DHEA supplementation is heavily commercialized with claims that it is an antiaging remedy, will increase muscle, decrease fat, and improve energy, strength, and immunity. There are cell culture data indicating that an inhibition of bone resorption and serum levels of DHEA appear to relate to rates of bone loss in a cohort study . Clinical trials have conflicting or inconsistent data regarding the skeletal site and gender-specific benefit of DHEA . Although DHEA may have some skeletal benefit, the benefit may be limited to elderly individuals with low serum levels at baseline . A pooled analysis of data from four double-blind, randomized controlled trials included 295 women and 290 men over the age of 55 years who took DHEA (50–75 mg/day) or placebo tablet daily for 12 months. In this analysis, women on DHEA had increases in lumbar spine and trochanter BMD and maintained total hip BMD; however, men had no BMD benefit but did show a decrease in fat mass . The safety concerns with the use of DHEA include adverse effects on liver function, masculinizing effects and increased risk of acne.

DHEA replacement therapy may be beneficial for bone health, potentially through inhibition of skeletal catabolic IL-6 and stimulation of osteoanabolic IGF-I-mediated mechanisms . Older men in the Osteoporotic Fractures in Men (MrOS) Sweden study with high DHEA or DHEA-S levels had a decreased likelihood of a fall, and this was only partially mediated via muscle mass, muscle strength, and/or balance . Clearly this could have a potential impact on fracture rates. In fact, in the same cohort of men, low serum DHEA-S levels were related to an increase in nonvertebral fractures in older men; those with DHEA-S levels below 0.60 μg/mL were at highest risk .

71.4

Antioxidants

Oxidative stress is a potential cause of many diseases and may be a major mechanism in the loss of bone mass and strength. Aging results in an increase in reactive oxygen species that have been shown to affect the generation and survival of osteoclasts, osteoblasts, and osteocytes . Therefore antioxidants have been studied in their role to prevent disease and promote health, including flavonoids (including quercetin), omega-3 fatty acids, carotenoids, vitamin A, vitamin C, and vitamin E. Beyond their antioxidant potential, these compounds may provide skeletal benefit by creating a more alkaline environment, reducing urinary calcium excretion, or providing other bioactive components (phenols and flavonoids). High intakes of these nutrients might also be markers for healthy lifestyle.

71.4.1

Flavonoids

Flavonoids occur in plant-based foods, including fruits, vegetables, grains, herbs, tea wine, and juices. Flavonoids are further classified as flavanones, anthocyanins, flavan-3-ols (green tea), polymers, flavonols, flavones, and isoflavones (discussed earlier). Higher intakes of flavonoids have been positively associated with spine and hip BMD . Quercetin is a member of the flavonoid family and is also a strong antioxidant with potential to benefit bone health . Quercetin can be found in citrus fruits, apples, onions, parsley, sage, tea, and red wine, as well as many food supplements. Epidemiologic studies of tea-derived flavonoids, from both black and green tea, have reported mixed results on BMD and risk of fracture . An Australian cohort study reported that in comparison with the lowest tea intake category (≤1 cup/week), consumption of ≥3 cups/day was associated with a 30% decrease in the risk of any osteoporotic fracture [hazard ratio (HR): 0.70; 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.50, 0.96]. Compared with women in the lowest tertile of total flavonoid intake (from tea and rest of diet), women in the highest tertile had a lower risk of any osteoporotic fracture (HR: 0.65; 95% CI: 0.47, 0.88), major osteoporotic fracture (HR: 0.66; 95% CI: 0.45, 0.95), and hip fracture (HR: 0.58; 95% CI: 0.36, 0.95) . However, without more data, the best advice would be to get flavonoid compounds from fruits and vegetables, instead of from a supplement.

71.4.2

Omega-3 fatty acids

There are several sources of omega-3 fatty acids, including fish, eggs, walnuts, and flaxseed. Nutritionally, essential omega-3 fatty acids are polyunsaturated fatty acids: α-linolenic acid, eicosapentaenoic acid, and docosahexaenoic acid. Omega-3 fatty acids may affect the skeleton not only by their antioxidant function but also by upregulating intestinal calcium absorption . The effect of omega-3 fatty acids on BMD has been variable, but there are positive associations between omega-3 intakes and BMD in younger and older adults . In addition, dietary intake of omega-3 was inversely associated with risk of hip fracture (pooled effect size: 0.89, 95% CI: 0.80–0.99, P =.02) and remained significant after analysis of only prospective studies (pooled effect size: 0.88, 95% CI: 0.80–0.98, P =.02) .

It may be that a higher ratio of omega-6 (polyunsaturated fat found in vegetable oils, poultry, some nuts and seeds that are subject to oxidation with some potential for inflammation) to omega-3 fatty acids is negatively associated with BMD , although the relationship is not clear . It is possible that a lower ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 may be positively associated with bone health , so it would be better to obtain omega-3 from dietary sources such as walnuts and fish oils and flaxseed oil, and limit sources of omega-6 by reducing consumption of processed and fast foods and limiting those polyunsaturated vegetable oils with a higher amount of omega-6 as compared to omega-3 (corn, sunflower, safflower, soy, and cottonseed) and instead use oils with lesser omega-6 such as olive, coconut, or palm oils. In a review of the potential benefit of omega-3 fatty acids on skeletal health, it was also noted that higher concurrent calcium intakes may enhance the benefit of omega-3 .

71.4.3

Carotenoids

Carotenoids are fat-soluble plant pigments that have antioxidant properties and are found in various vegetables, including carrots, sweet potatoes, spinach, kale, collard greens, papaya, bell peppers, and tomatoes. Carotenoids exist in four forms: beta-carotene, alpha-carotene, gamma-carotene, and beta-cryptoxanthin that can each be converted to retinol (vitamin A). The other carotenoids lycopene, lutein, and zeaxanthin function as antioxidants but are not converted to retinol. Data regarding the relationship between carotenoids and BMD are inconsistent, whether the study is based on serum levels or dietary intake. Lower serum lycopene, cryptoxanthin, and beta-carotene concentrations have been associated with lower BMD . In other studies, foods containing higher amounts of carotenoids have been associated with higher BMD . In one study, higher total carotenoid and lycopene intakes were associated with reduced fracture incidence in women and men . In a case–control study with over 2000 Chinese participants, when compared with the lowest quartile of carotenoids, the multivariate-adjusted odds ratios (OR) for hip fracture for the highest carotenoid intake quartile were 0.44 (0.29, 0.68) (total carotenoids), 0.50 (0.29, 0.69) (beta-carotene), 0.55 (0.38, 0.80) (beta-cryptoxanthin), and 0.40 (0.27, 0.59) (lutein/zeaxanthin), respectively .

More information is needed regarding the role of carotenoids on bone health. However, with the limited observational data that are currently available, it would be best to get carotenoids from increasing the intake of vegetables.

71.4.4

Vitamin A

Retinol is the animal form of vitamin A and is found in liver, meats, eggs, milk products, and fatty fish. The daily recommended intake for vitamin A for men is 1000 mg of retinol equivalents (RE) and for women 800 mg RE. Excess vitamin A has been associated with decreased BMD and increased hip fracture rates in some but not all studies . In addition, higher levels of retinoic acid have been related to higher rates of hip fracture in a large case–control study . Vitamins that contain no more than 2000–3000 IU retinol are preferred, whereas beta-carotene doses are of no concern.

71.4.5

Vitamin C and vitamin E

Ascorbic acid (vitamin C), a water-soluble vitamin, can be found in citrus fruits and juices, green vegetables (especially peppers, broccoli, and cabbage), tomatoes, and potatoes. Vitamin C is important in collagen formation and may also provide skeletal benefit as an antioxidant. For adults, the recommended daily amount for vitamin C is 75 mg a day for women and 90 mg a day for men, and the upper limit is 2000 mg a day.

Nuts, seeds, and vegetable oils are among the best sources of vitamin E as alpha-tocopherol, and significant amounts are also available in green leafy vegetables and fortified cereals. For adults the daily amount of vitamin E is 15 mg (22.4 IU) and the tolerable upper limit is 1000 mg (1500 IU).

In a small clinical trial, vitamin E (400 mg) and vitamin C (1000 mg/day) supplements taken for 6 months slightly reduced spinal bone loss and reduced bone resorption in another cohort . In a case–cohort analysis among 1168 hip fracture cases and 1434 controls over age 65 in Norway, low serum concentrations of α-tocopherol were associated with increased risk of hip fracture .

Low intakes of vitamin C have been associated with a faster rate of bone loss in women of varying ages, and one study found that higher vitamin C was associated with fewer fractures . Men with the highest vitamin C intake had significantly less bone loss than men in the lowest group of vitamin C intake . Vitamin C intakes may also interact with estrogen use, calcium, and vitamin E in women . Subjects in the highest tertile of total vitamin C intake (mostly from supplements) had significantly fewer hip fractures ( P trend=.04) and nonvertebral fractures ( P trend=.05) compared to subjects in the lowest tertile of intake . In a metaanalysis of six articles, containing 7908 controls and 2899 cases of hip fracture, dietary vitamin C was inversely associated with the risk of hip fracture (overall OR=0.73, 95% CI=0.55–0.97), and an increase of 50 mg/day vitamin C intake was related to a 5% reduction in hip fracture risk . However, in the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study, increasing intakes of antioxidants (including vitamin C) were not associated with BMD .

In many studies, it is not possible to separate the effects of vitamin C supplements from vitamin C in fruits and vegetables . Therefore the recommendation is to obtain the needed amounts of vitamin C from fruits and vegetables, rather than from supplements. This may have positive effects on BMD at all ages . Recommended intakes of five or more servings of fruits and vegetables per day should supply enough vitamin C for bone health.

71.4.6

Vitamin K

The major forms of vitamin K are phylloquinone (vitamin K1) found in green leafy vegetables such as spinach, kale, broccoli, and menaquinone (vitamin K2) found in meat, eggs, dairy, cheese, and natto. Dietary K2 accounts for about 10% of total vitamin K intake. The most common sources of vitamin K in the US diet are spinach, broccoli, iceberg lettuce, and soybean and canola oil. For adults the recommended daily amount for vitamin K is 90 μg a day for women and 120 μg a day for men. There is no tolerable upper limit since no adverse effects have been associated with vitamin K consumption from food or supplements. Vitamin K deficiency leads to a decrease in the carboxylation of osteocalcin, and vitamin K treatment will reduce undercarboxylated osteocalcin . It is unclear whether K1 and K2 have differential effects on BMD.

Serum vitamin K has been found to be lower in persons with lower bone mass, osteoporosis, or fractures . Vitamin K supplementation has no effect on BMD or a positive effect, but only on hip BMD in randomized clinical trials, data are conflicting and unclear . In a metaanalysis of phylloquinone (vitamin K1), there was an inverse association between dietary vitamin K1 intake and risk of fractures (highest vs the lowest intake, RR = 0.78, 95% CI: 0.56–0.99; I = 59.2% .

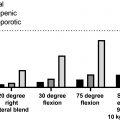

Natto capsules of MK-7, a form of K2, had no effect on BMD after 12 months . However, in a study of MK-7 (375 µg) given for 12 months, MK-7 prevented age-related loss of trabeculae and minimized increased trabecular spacing at the tibia as measured by high resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography (HR-pQCT) .

Clinical trials of 200–500 μg vitamin K1 (phylloquinone) have had little effect on the skeleton . In a trial with postmenopausal women with low bone mass, 5 mg of daily vitamin K1 supplementation for 2–4 years did not protect against age-related decline in BMD but protected against clinical fractures , although there were very few incident fractures in the 4 years and clearly results need to be confirmed.

At larger (pharmacologic) doses, 45 mg of K2 led to modest increments in BMD at various skeletal sites . Pooling fracture data from seven trials in a metaanalysis, the OR favored high-dose K2 as menaquinone over placebo for vertebral fractures, hip fractures, and for all nonvertebral fractures . However, this result has been recently updated given recently identified problems, including small sample size, small number of events and an apparently high-risk population. The authors were not comfortable stating that there might be a clinically important difference in fracture rates using vitamin K supplements .

In general, patients should be encouraged to consume a diet rich in vitamin K, including green leafy vegetables and certain vegetable oils. Fracture prevention with vitamin K appears limited to high doses of vitamin K2 as menaquinone and to specific populations (Japanese women) . Therefore supplementation is not recommended until beneficial results are confirmed in larger trials with varying populations. Any differences between vitamin K1 and K2 need to be further explored. Individuals on oral anticoagulants such as warfarin should avoid high intakes of vitamin K through diet or supplements.

71.4.6.1

Summary

Fruits and vegetables may reduce urinary calcium excretion, create an alkaline environment, provide specific nutrients, provide an antioxidant effect, provide bioactive components (phenols and flavonoids), or they may simply be a marker for a healthy lifestyle. Therefore foods, rather than supplements, may be the best way to get the benefit of antioxidant compounds and vitamins, because they may also provide skeletal benefit through other mechanisms.

71.5

Bicarbonates

An acidic environment is associated with a negative skeletal impact . Bicarbonate (HCO 3 ) may improve bone health by decreasing 24-hour urinary calcium, promoting calcium absorption and perhaps lowering bone resorption . Sodium bicarbonate is simply baking soda; however, potassium bicarbonate is found in fruits and vegetables, such as bananas, potatoes, and spinach. A potassium citrate supplementation for 2 years did not reduce bone turnover or increase BMD in healthy postmenopausal women as compared to placebo . Further study may help to elucidate the effect of the bicarbonate as compared to the effect of potassium, and how this relates to baseline acidogenicity of the diet .

In an analysis of NHANES data of adults over age 20, lower serum bicarbonate levels were associated with lower BMD at the spine and total body, and this association was stronger among women, in particular postmenopausal women than men .

In a longitudinal study, plasma HCO 3 was positively associated with baseline BMD and inversely associated with the rate of bone loss at the total hip .

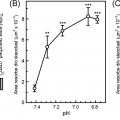

In a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study, 244 men and women age 50 years and older were randomized to placebo or 1 or 1.5 mmol/kg of KHCO 3 daily for 3 months. When compared with placebo, urine calcium excretion was reduced by 169% on the lower dose and by 213% on the higher dose of KHCO 3 and the lower, but not higher dose, reduced bone resorption [urinary N-terminal telopeptide (NTX)], by 18.7%, and bone formation (serum P1NP) by 10.7% .

Longitudinal studies and long-term randomized controlled trials are needed to determine the effect of alkali on bone mass and fracture risk.

71.6

B vitamins and homocysteine

Vitamins B6 (pyridoxine), B9 (folate), and B12 (cyanocobalamine) are water-soluble vitamins that have been reported to have a skeletal benefit. The vitamin B6 recommended intake depends on age and sex and is 1.5 mg for women over 50, and 1.7 mg for men over 50. Food sources of pyridoxine (B6) are whole grains, fortified cereals, liver, soybeans, and beans. The recommended daily amount of folate for adults is 400 μg. Folate (vitamin B9) dietary sources include dark green leafy vegetables, whole-grain breads, nuts and fortified cereals, and the folic acid that is added to fortified foods. The recommended dietary allowance (RDA) of vitamin B12 for adults is 2.4 μg. Vitamin B12 is found in liver, shellfish, fish, beef, lamb, cheese, eggs, and fortified foods.

Homocysteine has recently been linked to fragility fractures, including hip fractures in older men and women , and elevated serum homocysteine levels may be caused by deficiencies of folate (folic acid), vitamin B12, or vitamin B6. In individuals who have vitamin B or folate deficiency, serum homocysteine concentrations are known to increase, and it may be those exhibiting increased homocysteine may also have a polymorphism in methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase, MTHFR (C677T: TT type), which regulates homocysteine metabolism . The role of B vitamins in skeletal health has been the subject of many recent research studies.

In one study, low serum folate was shown to be responsible for the association between higher homocysteine levels and greater risk of osteoporosis-related fractures in the elderly . Poor vitamin B12 status has also been associated with low bone mass or osteoporosis in both women and men ; however, this may be compounded by overall poor nutrition and increased frailty. Low serum B vitamin concentrations, particularly folate, were noted to be a risk factor for poor bone health . In a population-based study of more than 18,000 men and women, high homocysteine levels were associated with decreased BMD and an increased risk of osteoporosis. An independent relationship between higher dietary intake of pyridoxine (B6) with higher BMD and reduced fracture risk was reported in a group of over 5000 individuals . Folate has also been found to be more strongly related to BMD than any other B vitamin in some but not all studies . In a Japanese study, 5 mg folic acid and 1500 μg mecobalamin (a form of vitamin B12) daily for 2 years reduced hip fractures as compared to placebo, but the population was exclusively stroke patients and the B12 doses were very high .

Controlled trials to determine whether treatment with any of the B vitamins would reduce fracture rates among community-dwelling cohorts are needed . One such trial in The Netherlands [B vitamins for the PRevention Of Osteoporotic Fractures (B-PROOF)] was a 2-year double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial in 2919 participants aged ≥65 years with elevated homocysteine concentrations (12–50 μmol/L) who were assigned to receive daily 500 μg vitamin B12 plus 400 μg folic acid or placebo supplementation. Combined vitamin B12 and folic acid supplementation had no effect on the incidence of osteoporotic fractures in the intention to treat analysis. Exploratory subgroup analyses suggested a beneficial effect on osteoporotic fracture prevention in compliant persons aged >80 years; however, treatment in this subgroup was also associated with increased incidence of colorectal and gastrointestinal cancer . In the Aspirin/Folate Polyp Prevention Study, 1021 participants were randomized to a daily folic acid dose of 1 mg ( n =516) or placebo ( n =505), and folic acid was not related to fractures of any type, including hip, in a secondary analysis. In addition, a metaanalysis of six RCTs with 36,527 participants found that folic acid and/or vitamin B12 failed to lower fracture risk . In a secondary analysis of combined data from two large randomized controlled trials designed to study cardiovascular diseases, treatment with folic acid plus vitamin B12 was not associated with the risk of hip fracture. Treatment with a high dose of vitamin B6 was associated with a slightly increased risk of hip fracture during the extended follow-up . In the Women’s Antioxidant and Folic Acid Cardiovascular Study, there was no significant effect of B vitamin supplementation on nonspine fracture risk (relative hazard=1.08; 95% CI, 0.88–1.34) in women at high risk of cardiovascular disease. Furthermore, in a nested case–cohort analysis, there were no significant effects of B vitamins on fracture risk among women with elevated plasma homocysteine levels, or low levels of vitamins B12 or B6, or folate at baseline .

At this point the weight of the evidence suggests that there is no benefit for B vitamin supplementation in fracture reduction. In one subgroup analysis of those over 80 years of age, there was even concern regarding an increase in cancer risk. As for the other nutrients, it would be best to promote a healthy varied diet to assure adequate intake of B vitamins.

71.7

Minerals

71.7.1

Magnesium

Magnesium is the fourth most abundant mineral in the human body, and food sources include green vegetables such as spinach, legumes (beans and peas), nuts and seeds, and whole, unrefined grains. Magnesium is a shortfall nutrient, and over half of adults do not meet the RDA of 320 mg/day for females and 420 mg/day for males .

A positive relationship between bone mass and dietary magnesium intake was found in young women , although results are not consistent across all skeletal sites. In postmenopausal women and older men, positive correlations between BMD and magnesium intake have been found, although results are not consistent based on gender and race . Magnesium supplementation was primarily effective for bone health in magnesium-depleted subjects based on baseline serum magnesium levels . Overall, observational and clinical trial data concerning magnesium and BMD or fractures are inconclusive . In the largest prospective cohort study, 73,684 postmenopausal women in the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study, total daily magnesium intake, as estimated from baseline food-frequency questionnaires plus supplements, was associated with lower BMD of the hip and whole body, but not an increased risk of fractures. Magnesium consumption slightly greater than the RDA is associated with increased lower arm and wrist fractures that may be related to more physical activity and falls .

A metaanalysis on magnesium intake and BMD or fracture found that high intakes of magnesium were not associated with increased risk of hip and total fractures. Magnesium intake was modestly correlated with BMD in femoral neck and total hip, but not the spine . In a longitudinal cohort of persons at risk for osteoarthritis, 3765 participants with a mean age of 60·6 years were followed for 8 years and after adjusting for 14 potential confounders at baseline and taking those with lower Mg intake as reference (Q1), men (HR 0.47; 95% CI 0.21, 1.00, P =.05) and women (HR 0.38; 95% CI 0.17, 0.82, P =.01) in the highest quintile reported a significantly lower risk for fracture. In fact, women who consumed the recommended Mg intake were at a 27% decreased risk for future fractures .

In healthy adults, recommending an increased intake of food sources high in magnesium [spinach, legumes (beans and peas), nuts and seeds, and whole, unrefined grains, milk or soy milk] would be beneficial. There is little evidence that magnesium as a supplement is needed to prevent osteoporosis in the general population. However, a magnesium supplement may be required in those with low magnesium levels, including frail elderly with poor diets , patients with intestinal disease, alcoholics, or those on treatment with diuretics or chemotherapy that deplete magnesium.

71.7.2

Boron

Boron is not an essential nutrient, so therefore RDAs have not been determined. Boron is present in several foods, such as fruits, vegetables (potato and avocado), legumes, nuts, eggs, milk, wine, and dried foods . Whether a low intake is of clinical concern is unknown. A few studies have found that 3 mg daily of boron may have a positive effect on bone , perhaps through a decrease in urinary calcium loss , but controlled trials are lacking. Boron has also been noted to stimulate bone growth and bone metabolism and to activate 1,25(OH)2D3 production and bone mineralization . It is suggested that foods such as fruits, vegetables, and legumes are potential sources of boron.

71.7.3

Silicon

Silicon is a trace mineral that may be essential for skeletal and connective tissue formation , although there is no official recommended daily amount of silicon. Cereals provide the greatest amount of silicon in the US diet, followed by fruit, water, beer, high-fiber grains, bananas, and vegetables. There is a decrease in serum silicon concentrations that occurs with age, especially in women . The biological role of silicon in bone health remains unclear but may relate to effects on the synthesis of collagen and/or its stabilization and on matrix mineralization .

Dietary silicon intake was found to have a positive association with BMD , although the effect varied with age . In the Aberdeen Prospective Osteoporosis Screening Study cohort of 3198 women aged 50–62 years ( n =1170 current hormone therapy users, n =1018 never used hormone therapy), dietary silicon was estimated by food-frequency questionnaire. In this study, there was an interaction between estrogen status and quartile of energy-adjusted silicon intake on femoral neck BMD that was significant after adjustment for confounders and stronger for bioavailable silicon . Any potential positive association between silicon and skeletal health requires further follow-up and confirmation.

71.7.4

Strontium

Strontium is a mineral that is absorbed in the body like calcium. Common salts of strontium include strontium ranelate, strontium citrate, and strontium carbonate. Strontium is found in seawater and soil, so seafood, whole milk, wheat bran, meat, poultry, and root vegetables may contain small amounts. Pharmacologic doses of strontium ranelate were approved in several European countries for the treatment of osteoporosis, but never in the United States. The European approvals were subsequently withdrawn due to safety concerns regarding cardiovascular and skin disease. In clinical trials, strontium reduced the risk of vertebral fractures and nonvertebral fractures . Strontium may be a modest antiresorptive agent. Strontium is incorporated into hydroxyapatite, replacing calcium, a feature that might contribute to dramatic increases in BMD. The most common side effects of strontium ranelate were nausea, diarrhea, headache, and skin irritation as well as small increased risks of venous thrombosis, seizures, and abnormal cognition .

There are many strontium salts that are available through the Internet. However, their long-term safety and efficacy have not been evaluated in large-scale clinical trials. Websites for many strontium compounds reference data from strontium ranelate clinical trials as proof of efficacy of their particular compound, even though they are marketing a different strontium compound. Various formulations often contain amounts of elemental strontium that vary from the strontium ranelate used in clinical trials. The dose, absorption, and bioequivalence of the many forms of strontium available for purchase are not known. There are no clinically relevant data to support that any of these compounds available, without a prescription, will build bone mass or prevent fracture. In addition, the safety of these compounds is unknown.

71.7.5

Phosphorus

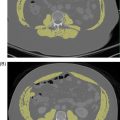

Phosphorus is a mineral with an RDA of 700 mg a day for adult men and women. Phosphorus is a component of dairy foods, meat, eggs, cereal, and processed foods. Phosphoric acid is also found in cola-type sodas. The diets of many individuals have a disproportionately high intake of phosphorus as compared to calcium . Higher consumption of cola beverages was associated with lower BMD in women but not men , and higher phosphorus intake was related to higher fracture rates . These data are preliminary and require further study, though a recent review concluded that diets high in foods containing inorganic phosphate additives at levels typical in the United States can adversely alter bone and mineral metabolism . In general, high dietary phosphorus increases parathyroid hormone (PTH) , although if dietary calcium intake is also increased, this does not occur . In general, dietary phosphorus has not been related to BMD , although the calcium to phosphorus ratio may be important for BMD and fracture risk . In two cohort studies, serum phosphate was positively related to fracture risk, where there was a 47% increased risk of fracture with each 1 mg/dL increase in serum phosphate after adjusting for multiple covariates .

71.8

Conclusion

Calcium and vitamin D play a clear role in bone health and in cases of low dietary intake of calcium, supplementation may be needed, but the first choice is to consume calcium from foods. In most cases vitamin D supplementation is needed to ensure adequate intake. Some nutraceutical products may also promote skeletal health; however, existing studies often provide inconsistent outcomes and conclusions. This may relate to differences in study design, small sample sizes, and methodological flaws in addition to inconsistent formulations. Potential safety issues must be recognized when these nutraceutical products are taken in amounts that exceed dietary recommendations. Furthermore, only short-term data are available for either efficacy or safety. It is important that medical providers are aware of the nutraceuticals commonly used by their patients and to have an understanding of the safety, efficacy, and lack of regulation of these products. For many nutraceuticals the marketed doses are equivalent to pharmacologic levels, not equivalent to what is found in food. Clearly, for patients with osteoporosis or with a high risk for fracture, nutraceuticals will not replace medication proven to prevent fractures.

References

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree