Introduction

Nursing home facilities are more unique than similar. The care of elderly persons in institutionalized settings varies by country and region and in societal and cultural factors. Nursing homes also rapidly evolved because the quality of nursing home care has become a growing concern everywhere and because residents are generally showing increasing levels of disability and require increasingly more complex treatments. However, this evolution relies more on empirical practice than research studies. Only 2% of the research into the elderly population concerns nursing home residents.1

Approaches to long-term care in various countries include chronic geriatric hospitals, short-stay rehabilitation centres, residential living centres and institutionalized skilled nursing homes. The nomenclature of a facility varies across settings, including ‘nursing home’ in the United States and ‘care home’ in the United Kingdom. A ‘nursing home’ in the USA may refer to a specialized centre for persons on ventilators, with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome or with dementia who need skilled nursing care. A ‘care home’ in the UK generally refers to a home registered under the Care Standards Act providing personal and residential care for older people and also includes homes that provide nursing care (nursing homes). Not only is the classification confusing, but also the public, and often the professional, view of nursing homes involves a number of misperceptions.

Misperception: most older adults will live for many years in a nursing home and eventually die there. Truth: fewer than 5% of older adults in USA and fewer than 10% in the UK and France reside in resident and nursing home settings.

Misperception: once a person enters a nursing home, they stay there for good. Truth: many older adults who enter a nursing home will recover and leave (short-stay residents), while fewer older adults will remain in a nursing home once admitted (long-stay residents). In France, half of the nursing home residents will also have a hospitalization every year.1

Misperception: nursing homes are warehouses for older persons with little or no stimulation: Truth: a good home provides a social environment that often is very comforting for older persons who may have been isolated in previous living environments.

Misperception: no one likes living in a nursing home. Truth: many residents prefer the reassurance of medical care, socialization and a safe environment and find the experience positive.

Facility Demographics

In the USA, there are ∼16 100 nursing homes with ∼1.5 million residents. The number of nursing home beds decreased in the USA from 19992 to 20043 from 1.9 to 1.7 million beds, respectively. The average number of beds per facility rose to 108 from 105. The occupancy rate (number of residents divided by number of available beds) was 86%. However, the demographics of facilities vary by country. In France, the number of beds in nursing homes is about five times higher (about 10 000 nursing homes for 60 million inhabitants with a bed occupancy close to 97%).

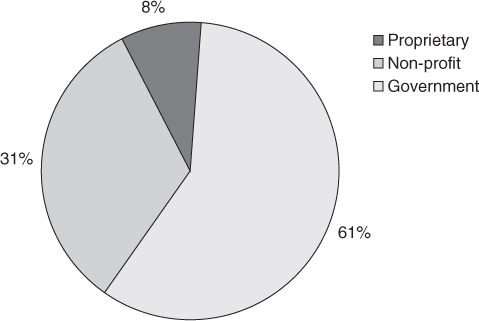

Ownership of most nursing homes in the USA is by for-profit entities (61%); 31% operate as voluntary non-profit facilities and the remaining 8% are owned by governmental entities (Figure 140.1). Half of the nursing homes are public in France. In the USA some 56% of nursing homes are affiliated with other nursing homes in a chain ownership. These facilities account for 57% of all beds, 57% of all residents and 61% of all discharges. Most nursing homes (62%) are located in a metropolitan statistical area.4 The distribution of nursing homes is uneven, with the midwestern and southern US census regions having 34 and 32% of facilities and 32 and 33% of all beds, respectively.

Figure 140.1 Percentage distribution of nursing home facilities by ownership: United States, 2004. Source: Jones AL, Dwyer LL, Bercovitz AR and Strahan GW. The National Nursing Home Survey: 2004 overview. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat 2009;13(167):1–155.

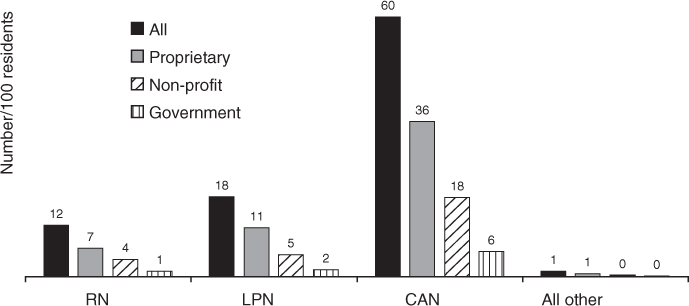

The nursing home industry employs a large number of persons in various occupations (Figure 140.2). The rate of staffing does not appear to vary much by type of nursing home ownership. A major problem for patient care in nursing homes is the high staff turnover rate. A vacancy rate of 19% for nurses has been reported.5 The turnover rate for nursing assistants has been reported to be as high as 93%.6 These high vacancy rates disturb continuity and force continuous training of new personnel. This nursing home staff turnover impacts on the quality of care.7

Figure 140.2 Number per 100 residents of full-time equivalent employees by occupational categories and selected nursing home characteristics: United States, 2004. CNA, certified nursing assistant; LPN, licensed practical nurse; RN, registered nurse. Source: Jones AL, Dwyer LL, Bercovitz AR and Strahan GW. The National Nursing Home Survey: 2004 overview. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat 2009;13(167):1–155.

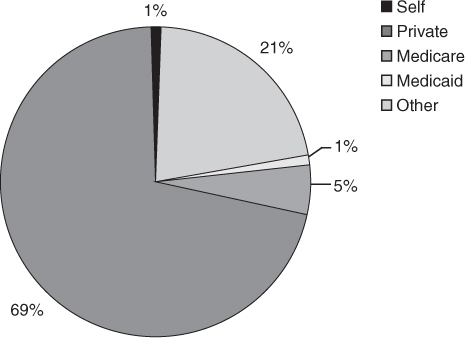

Nursing home care is expensive. Residents in US nursing homes use several sources of payment (Figure 140.3). At admission, most residents reported private resources (42%) as a payment source, followed by Medicare (36%) and Medicaid, a means-tested governmental source in the USA (35%). However, during admission, residents using Medicare as a source of payment dropped to 13% of all current residents. Longer term residents reported private sources increasing to 66%, and those with Medicaid rose to 60%. The national cost of nursing home care was $53 billion in 1990 and was the fastest growing component of major healthcare expense in the national budget.8 The projected cost for 2000 exceeded $140 billion and it may exceed $700 billion by 2030.9

Figure 140.3 Nursing home payment source: long-term stay >90 days: United States, 2004. Source: Jones AL, Dwyer LL, Bercovitz AR and Strahan GW. The National Nursing Home Survey: 2004 overview. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat 2009;13(167):1–155.

These predictions of continued nursing home growth and expenditures are becoming modified by several societal changes. The proportion of Medicaid beneficiaries aged 65–74 years residing in nursing homes remained fairly constant at about 6% from 1999 to 2003, but the percentage of Medicaid recipients aged 85 years and older declined from 48 to 44% from 1999 to 2003. This does not reflect a decrease in Medicaid recipients, who increased from about 4.2 million in 1999 to 4.8 million in 2003.

The growth in community-based care alternatives to nursing homes, such as assisted living and other group residential options, has been suggested as one of the reasons for the shrinking nursing home population in the USA. However, there is considerable variability at the State level in the availability and provision of home- and community-based services to people with long-term care needs.10 Because of the expense of nursing home care, several States have initiated programmes to favour home-based services financially. These trends will define the future number of nursing home beds required to care for the ageing population.

Nursing homes in other cultural settings differ considerably. For example, the Dutch experience demonstrates that among persons older than 65 years, ∼20% had a short stay in an inpatient hospital department and 96% were discharged to their own home situation. Only 7% lived permanently in special institutions for chronic care, including residential care or nursing home care. Persons with physical disability or with progressive dementia, who have impaired activities of daily living (ADLs) and who need more complex continuing care beyond the range of home care services in a residential homes, are admitted to a nursing home. The number of nursing home beds is 3.6 per 1000 persons (in 2003), with a total of 330 nursing homes with ∼26 000 beds designed primarily for persons with physical problems and 32 000 beds in psychogeriatric wards for persons with dementia. Nursing home care is covered by a mandatory national insurance system, the Exceptional Medical Expenses Act. In addition to the funds from this national insurance, income- and household-dependent out-of-pocket payments are obligatory for persons admitted to nursing homes.11

In the UK, the number of patients in private or voluntary homes rose from 18 200 in 1983 to 148 500 in 1994.12 The number of institutional care beds for older persons doubled to 563 000 between 1980 and 1995. National Health Service beds accounted for less than 10% of the total in 1995 compared with 23% in 1980, while private and voluntary (not-for-profit) residential and nursing home beds increased to 76%.13

Persons in the UK receiving long-term care provided in care homes are required to meet financial means testing. Those who have assets, including the value of their homes (with some exceptions), above a limit (£23 250 in 2011) are required to pay the care home’s fees in full. Those with assets below the limit make a co-payment that is usually less than the full fee. For those with the lowest income and assets, this payment may be met from Income Support, the UK’s means-tested welfare benefit. Almost all older people who own their home would be required to meet care home fees in full. The same approach exists in France. The children are also constrained by a law obligating them to pay if the payment cannot be met by the resident.

Means testing dates back to 1948 in the UK and has changed little in the many years since then. However, the growing numbers of older persons and increasing home ownership have stressed the means test. Local public authorities are responsible for payment for long-term care for older persons who meet means test requirements, whether in a care home or in the person’s own home. For care services delivered at home, the value of an older person’s home is disregarded in determining how much he or she contributes. An older home owner is, therefore, likely to incur considerably more—and the public budget correspondingly less—of the cost of care in a residential setting than of the equivalent cost of care at home. The result is a financial incentive for public authorities to arrange for a home owner’s care to be provided in an institution rather than in their own home. The financial incentive works in the opposite direction for older home owners themselves. Whether the likelihood of entry to a care home is increased or decreased by the level of an individual’s economic resources would seem to depend on whether individual choice or the policy of the local public authority dominates.14

Resident Demographics

In the USA, 43% of persons who were 65 years of age in 1990 will enter a nursing home in their lifetime. Of these, 55% will stay for at least one year and 21% will stay for five years or longer.15 The percentage of retired patients who will pass through a nursing home during their lifetime is nearly double in some European countries.

Nursing home use is strongly associated with age, even after adjusting for disability. This suggests that the future need for nursing home care will increase as the population increases in life expectancy. By 2030, the need for nursing home beds in the USA is projected to increase to 5 million.16, 17

Most nursing home admissions are for short-stay residents. About 2.5 million residents are discharged after an average length stay of 272 days. Long-stay residents remain in the nursing home for an average of 873 days.

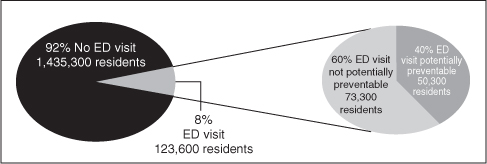

In France, 70% of nursing home admissions come from hospital. Most of the time, the mean length of stay does not reflect the rapid turnover of a small proportion of the nursing home residents who died after a short stay while others stay for a longer period.1 The changes in acuity and dependence in most countries18 result in increased needs such as care in the emergency department (Figure 140.4).1, 3

Figure 140.4 Percentage of nursing home residents with a potentially preventable emergency department (ED) visit in the past 90 days: United States, 2004. Source: CDC/NCHS, National Nursing Home Survey, 2004, http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db33.pdf (last accessed 7 November 2011).

Residents in nursing homes do not reflect the demographics of the general population. In the USA, most nursing home residents (71%) are female. Some 88% were aged 65 years and older and 45% were aged 85 years and older. The average length of time from admission for all nursing home residents was 835 days in 2004. The median length of time from admission was 463 days. Among nursing home residents aged 65 years and older, time from admission was less than 3 months for 19% of residents, 3 months to less than 1 year for 24% of residents and 1 year or more for 56% of residents. More than half of all nursing home residents were either totally dependent or required extensive assistance in bathing, dressing, toileting and transferring. In France, the mean age is about 84 years in a nursing home.

Nursing homes provide extensive services to residents. Almost all nursing homes reported providing nursing services (100%), medical services (97%) and personal care services that included ADLs (97%). Non-medical services most frequently offered by nursing homes include nutrition (99%), social services including assistance to residents and their families in handling social, environmental and emotional problems (98%) and physical therapy (97%). The least frequently offered services include hospice services (72%) and home health services (23%).

Nursing Home Regulation

In the USA, nursing homes are licensed by each state and require a certificate of need to operate. Each State regularly surveys nursing homes for compliance with State regulations. In addition, the Federal government contracts with each State to survey nursing homes for compliance with Federal regulations if the home receives payments from Medicare or Medicaid sources. Nearly all nursing homes (96%) have some form of certification. More than three-quarters of all facilities were certified by both Medicare and Medicaid. Only 4% of the 16 000 nursing homes were not certified.

Federal regulations are contained in two Congressional Acts, the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1987 (OBRA ’87) and the Balanced Budget Act of 1997 (BBA ’97). OBRA ’87 had a major impact on general nursing care, including the introduction of the Minimum Data Set (MDS), requirements for a Medical Director and the reduction in physical and chemical restraints. Regulations based on BBA ’97 initiated the Prospective Payment System and consolidated billing. These Federal regulations have created standards of care in nursing facilities. The regulations resulting from OBRA ’87 are divided into two parts. First, the law is stated. These statements are labelled by ‘F-tags’ and a number. An ‘F-tag’ is jargon for the actual law published in the Federal Register. Second, an interpretive guideline follows the regulation. The guidelines comprise the instructions used by surveyors to determine compliance with the law. Failure to comply with State or Federal regulations can result in fines or in decertifying the facility from participation in Federal programmes. A comparison of Federal quality-of-care indicators is published on the Internet and updated at intervals.

In the autumn of 2009, a new Minimum Data Set (MDS version 3.0) was implemented in the USA. Residents, families, providers, researchers and policymakers had expressed concerns about the reliability, validity and relevance of MDS 2.0. Some argued that because MDS 2.0 fails to include items that rely on direct resident interview, it fails to obtain critical information and effectively disenfranchises many residents from the assessment process. The new version MDS 3.0 was designed to improve the reliability, accuracy and usefulness of the MDS, to include the resident in the assessment process and to use standard protocols to evaluate nursing home residents.

A national testing of the MDS 3.0 was conducted in 71 community nursing homes in eight US States and in 19 Veterans’ Administration nursing homes. The evaluation tested data reliability, the validity of new cognitive, depression and behaviour items, response rates for interview items, user satisfaction and feedback on changes and time to complete the assessment.

Improvements incorporated in MDS 3.0 produced a more efficient assessment with greater reliability and shorter completion time. A key component of MDS 3.0 was a focus on direct interviewing of the resident. For areas such as cognition, mood, preferences and pain, studies have repeatedly shown that staff or family impressions often fail to capture the resident’s (or any adult’s) real condition or preferences. Published measures of clinical conditions were incorporated into MDS 3.0 to increase validity. A direct-interview pain assessment, the Geriatric Pain Assessment,19 uses resident self-report to obtain pain information. The pain severity items include the 0–10 scale, a recognized scale that is used in other settings, and the verbal descriptor scale, which may be easier to answer for some residents with cognitive impairment. Depression is assessed using the PHQ-9 instrument.20 The Brief Interview for Mental Status21 assesses cognitive function. The Confusion Assessment Method22 evaluates delirium, an exceptionally common problem in nursing home residents.

In the UK, nursing homes are required to report on their quality-of-care activities each year and are also regularly visited by Health Care Inspectorate personnel.

Medical Care

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree