Fig. 1

Ratio of ENKL in malignant lymphoma among each country

3 Pathology and Phenotype

Histologically, lymphoma cells of ENKL show diffuse proliferation with angiocentric or angiodestructive growth pattern (Fig. 2a). The cytological spectrum is rather broad, and cell sizes range from small to large. Varying degree of infiltration of inflammatory cells is presented and sometimes accompanies necrotic changes. These conditions caused the misunderstanding of this tumor as a nonneoplastic condition, particularly for nasal lymphomas [1, 29]. Repeated biopsies are important for precise diagnosis of those cases. Uncommon case of ENKL with intravenous lymphoma is recognized occasionally (Fig. 3) [30]. This suggests that intravascular form of lymphoma is not B-cell specific.

Fig. 2

Histologic features of ENKL. Tumor cells show an angiocentric growth pattern with infiltrating inflammatory cells and necrosis (a). The neoplastic cells are positive for granzyme B (b) and Epstein-Barr virus, detected by EBER in situ hybridization (c)

Fig. 3

ENKL of intravascular lymphoma. A rare form of ENKL presents with intravascular lymphoma (a). The CD34 staining highlights the localization of lymphoma cells in the vessels (b). Lymphoma cells are positive for CD56 (c)

The lymphoma cells express NK-cell markers that include CD2, cytoplasmic CD3 (cyCD3), CD7, and CD56. Surface CD3 (sCD3), CD5, and T-cell receptor (TCR) are generally negative, and TCR genes show germline configurations. Cytotoxic molecules such as TIA-1, granzyme B, and perforin are also positive in this lymphoma (Fig. 2b). Lymphoma cells are also positive for Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), which is currently regarded as a hallmark of ENKLs [30]. The EBV in specimens can be detected by EBER in situ hybridization (Fig. 2c).

4 Clinical Presentation

ENKL mostly occurs in adults with median age of 40s to 50s and shows remarkable male predominance [3–6, 25–28, 31–34]. Upper aerodigestive tract, typically nose or paranasal area, is the most affected site of origin, followed by the skin and gastrointestinal tract. For ENKL with nasal origin, approximately half of the patients present with stage I disease and one fourth with stage II [3, 5, 26–28, 32]. Some patients show long-term limitation to the original site, mimicking chronic sinusitis. On the other hand, extensive-stage disease can rapidly progress with fever, bone marrow involvement, hemophagocytosis, and disseminated intravascular coagulation. In contrast to nasal cases, two thirds of extra-nasal ENKLs present with advanced stage [5, 6]. In the 4th WHO classification, both nasal and extra-nasal ENKLs are included in the same category of disease [1] but should separately be assessed for clinical management.

5 Differential Diagnosis

For precise diagnosis of ENKL, several NK-cell-associated diseases should differentially be diagnosed. Those include aggressive NK-cell leukemia (ANKL), lymphomatoid gastroenteropathy (LyGa), and chronic NK-cell lymphocytosis (CNKL).

5.1 Aggressive NK-Cell Leukemia

ANKL is a leukemic form of NK-cell malignancy and accounts for less than 1 % of the lymphoid malignancies [13, 19]. It predominantly occurs in younger patients than ENKL with a median age around 40 years without any sex predominance [35]. The disease progression is rapid, and patients frequently present with B symptoms, such as fever, night sweat, or body weight loss. Hematological manifestation of ANKL is that of leukemia, which includes circulating and bone marrow leukemic cells, neutropenia, anemia, and thrombocytopenia, but hepatosplenomegaly is also frequently recognized. Cutaneous or central nervous system involvement is uncommon. Leukemic cells present as large granular lymphocytes and express NK-cell antigens including CD2+, cytoplasmic CD3, CD7, CD16, and CD56. EBV is usually positive, but not exclusively [35, 36]. Expression of CD16 is more frequent in ANKL than in ENKL, reflecting the different maturation stage of NK-cells: the former from cytotoxic NK-cells and the latter from immunoregulatory NK-cells [37]. The genetic differences of ANKL and ENKL including genomic gain and loss were revealed by array-based comparative genomic hybridization [38]. Anthracycline-based chemotherapy showed only limited response, but efficacy of L-asparaginase has recently been documented. Dose-reduced SMILE or L-asparaginase mono-induction is recommended for treatment [39].

5.2 Lymphomatoid Gastroenteropathy

The LyGa or NK-cell enteropathy is characterized by a localized proliferation of NK-cells, mostly in the stomach, but less frequently in the intestine [40, 41]. Patients do not show specific symptoms, and most are found by chance through endoscopic examination or follow-up of gastric cancer. Macroscopic findings show protruded lesion(s) in the stomach with around 1 cm diameter with or without depression or ulcers. Histologic specimens show sheeted proliferation of NK-cells without any accompanying necrotic areas. EBV is negative and can be a hallmark of differential diagnosis from ENKL. Lymphoepithelial lesions are occasionally found, and eosinophilic granules are seen in proliferating NK-cells. Helicobacter pylori infection is often accompanied, but its significance remains uncertain. The lesions usually disappear without any medications, and the recurrences are rare. The most important point for this disease is to avoid chemotherapy for lymphoma.

5.3 Chronic NK-Cell Lymphocytosis

CNKL is characterized by a chronic increase of blood NK-cells without lymphadenopathy or organomegaly [42]. The term “lymphocytosis” is derived from its nonneoplastic nature without any cytogenetic abnormalities. However, peripheral blood counts and morphology of increased NK-cells resemble those of ANKL. EBV is usually undetectable in CNKL; hence, the examination of EBV may help the differential diagnosis [43]. Rare cases of CNKL were reported to develop to ANKL [44], but these may represent occult ANKLs in the category of CNKL rather than transformation. CNKL is sometimes associated with reactive conditions against viral infections or underlying solid tumors [42]. Examinations of whole body and watchful observations are thus recommended as managements of CNKL.

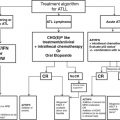

6 Treatment of ENKL

6.1 Limited Stages

Radiotherapy has been the mainstay for the treatment of ENKL with limited stage disease. Since anthracyclines and vincristine are exported from lymphoma cells of ENKL by p-glycoprotein [7, 8], the efficacy of CHOP/CHOP-like regimen was unsatisfactory [5, 45]. Radiotherapy should be given prior to [46] or simultaneous with chemotherapy [9, 10]. The chemotherapy to be combined with radiotherapy is not determined, but platinum-based regimens are preferentially used. The Japanese Clinical Oncology group conducted a phase II study of simultaneous chemoradiotherapy (SCRT) with 50 Gy irradiation and the 2/3 dose of DeVIC (dexamethasone, etoposide, ifosfamide, and carboplatin) (Table 1) [9]. Two thirds of DeVIC was repeated 3 cycles, and the total treatment period was 9 weeks. The study by Korean group adopted a cisplatin monotherapy for SCRT followed by 3 cycles of VIPD (etoposide, ifosfamide, cisplatin, and dexamethasone) regimen [10]. Both studies showed satisfactory results with 2-year OS of approximately 80 % (Table 2), and the long-term follow-up study of RT-2/3 DeVIC confirmed the durable efficacy with 5-year OS of 70 % [47].

Table 1

RT-2/3 DeVIC regimen

Agent | Dose | Administration | Days |

|---|---|---|---|

Radiotherapy | 1.8–2.0 Gy | (Total 50 Gy) | Days 1–33 or 38 (5–6 weeks) |

Carboplatin | 200 mg/m2 | 30 min div | Day 1 (22, 43) |

Etoposide | 67 mg/m2 | 2 h div | Days 1–3 (22–24, 43–45) |

Ifosfamide | 1000 mg/m2 | 3 h div | Days 1–3 (22–24, 43–45) |

Dexamethasone | 40 mg/body | 30 min div | Days 1–3 (22–24, 43–45) |

Table 2

Comparison of simultaneous chemoradiotherapy (SCRT) for localized ENKL

Regimen | RT-2/3 DeVIC | Korean CCRT |

|---|---|---|

Treatment period | 9 weeks | 16–20 weeks |

Radiation dose | 50 Gy | 40–50.8 Gy (median: 40 Gy) |

Cytotoxic agents | CBDCA | CDDP |

ETP | ETP | |

IFM | IFM | |

Dexa | Dexa | |

Chemotherapy | 3 courses | SCRT + 3 courses |

Number of patients | 27 | 30 |

Stage I ratio | 67 % | 50 % |

CR rate | 77 % | 73 % → 90 % (best response) |

ORR | 81 % | 100 % |

2y OS | 78 % | 86 % |

95 % CI | (57–89 %) | (74–99 %) |

Median f/u | 32 months | 23.7 months |

Range | (24–62 months) | (17.3–37 months) |

5y OS | 70 % | – |

95 % CI | (49–84 %) | – |

Median f/u | 67 months | – |

Range | (61–94 months) | – |

6.2 Advanced Stages, Relapsed or Refractory State

Systemic chemotherapy is required for advanced stage, relapsed or refractory ENKL patients. However, the efficacy of CHOP/CHOP-like regimen is limited because of the expression of p-glycoprotein [5]. Based on the clinical experience and in vitro sensitivity studies, L-asparaginase-containing regimens have been established and became the first choice for these patients [48]. L-asparaginase is an enzyme that digests serum L-asparagine and acts as an antitumor agent through asparagine starvation of tumors with low expression levels of asparagine synthetase [49]. The SMILE regimen consists of steroid, methotrexate, ifosfamide, L-asparaginase, and etoposide (Table 3) [50]. The phase II SMILE study showed an excellent antitumor activity to ENKL (Fig. 4) [11], and the efficacy was further verified by a long-term follow-up with a 3-year OS of 50 % (95 % CI, 33–65 %) [51]. Another L-asparaginase-containing regimen, AspaMetDex (L-asparaginase, methotrexate, and dexamethasone) was studied by GELA (Groupe d’Etude des Lymphomes de l’Adulte) and GOELAMS (Groupe Ouest-Est des Leuce’mies et des Autres Maladies du Sang) [52]. The phase II study of AspaMetDex for relapsed or refractory ENKL also showed a good overall response rate and 1-year OS [12]. However, results of a later-conducted study for newly diagnosed ENKL patients were rather unsatisfactory [53]. Although more than half of the patients were in localized stage, the ORR was 55 % (95 % CI, 32–77 %) and OS was less than 50 %. All patients examined developed an anti-asparaginase antibody, partly due to the low-intensity chemotherapy before L-asparaginase. The comparison of these two L-asparaginase-based chemotherapy is shown in Table 4. SMILE is sometimes myelotoxic to ENKL patients, but the duration of neutropenia is generally not so long (Fig. 5). It is therefore needed to identify patients who develop severe leukopenia and neutropenia after SMILE regimen.

Table 3

SMILE regimen

Agent | Dose | Administration | Days |

|---|---|---|---|

Methotrexate | 2 g/m2 | 6 h div | Day 1 |

Ifosfamide | 1500 mg/m2 | 3 h div | Days 2–4 |

Etoposide | 100 mg/m2 | 2 h div | Days 2–4 |

Dexamethasone | 40 mg/body | 30 min div | Days 2–4 |

L-asparaginase | 6000 IU/m2 | 2 h div | Days 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 18, 20 |

Table 4

Comparison of L-asparaginase-containing regimens for ENKL

Regimen | SMILE | AspaMetDex |

|---|---|---|

Agents | MTX | MTX |

L-asp | L-asp | |

Dexa | Dexa | |

ETP | ||

IFM | ||

Number of patients | 38 | 19 |

Course | 2 courses | 3 courses |

Chemotherapy interval | 4 weeks | 3 weeks |

Rate of stage III/IV patients | 71 % | 37 % |

CR rate | 45 % | 61 % (1 patient excluded) |

ORR | 79 % | 78 % |

2y OS | 51 % | 41 %

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|