Neutropenic enterocolitis, also known as typhlitis or ileocecal syndrome, is a rare, but important, complication of neutropenia associated with malignancy. It occurs as a result of chemotherapeutic damage to the intestinal mucosa in the context of an absolute neutropenia and can rapidly progress to intestinal perforation, multisystem organ failure, and sepsis. Presenting signs and symptoms may include fever, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Rapid identification and timely, aggressive medical and/or surgical intervention are the cornerstones of survival for these patients.

Neutropenic enterocolitis (NE) is a poorly understood disease, originally described as a complication of pediatric leukemia. NE typically presents with fever, abdominal pain, and abdominal distension. The integrity of the bowel wall is compromised either as a direct result of chemotherapy or as an indirect result of neutropenia, leaving the bowel vulnerable to bacterial invasion, necrosis, and perforation. Affected patients can progress rapidly to the sepsis syndrome along with multisystem organ failure, which made early cases of NE almost uniformly fatal. Outcomes have improved over time but depend heavily on a timely diagnosis and swift intervention. The diagnosis of NE is associated with a relatively high degree of morbidity and mortality. Reported mortality rates currently vary between 0.8% and 26%, but others still report rates between 50% and 100%.

Emergency department (ED) physicians are the front line of treatment for many neutropenic patients. Recent advances in cancer treatment are exposing patients to more advanced chemotherapeutic regimens, resulting in more frequent periods of absolute immunocompromise and hence more potential ED visits. This article discusses the clinical presentation of NE, effective diagnostic strategies weighing the relative utilities of ultrasonographic imaging versus computed tomography (CT), and treatment options examining surgical versus medical approaches.

Background and state of the evidence

Necrotizing enterocolitis has long been acknowledged in the pediatric literature but has been relatively rare in adult patients. Over time, the term neutropenic enterocolitis has evolved to better appreciate the role that neutropenia plays in the pathogenesis of this condition. Early reports date back to 1933, when Cooke observed submucosal hemorrhage and appendiceal perforation in leukemic children (cited in Cunningham and colleagues ). More contemporary reports date to 1962, with a case series by Amromin and Salomon (cited in Cunningham and colleagues ). They reported a large series of 69 adults with NE and acute leukemia or lymphoma over a 5-year period. These patients, characteristically, developed necrotizing enteric lesions shortly after intensive chemotherapy. Development of these enteric lesions was generally independent of patient response to chemotherapy. Interestingly, most patients experienced excellent therapeutic responses to their chemotherapy before the onset of NE. The patients almost uniformly experienced abdominal pain, distension, leukopenia, and intestinal necrosis with histologic evidence of bacterial invasion of the mucosa and submucosa of the bowel wall. All patients in this series succumbed to their disease after the development of NE. NE has also been termed ileocecal syndrome or typhlitis.

The literature discussing NE is varied and characterized by numerous case reports and case series, illustrating cases of NE across a spectrum of patients, both with and without cancer. There is, however, only a single analysis of the current state of evidence regarding NE by Gorschlüter and colleagues. In that review, no clinical trials or case control studies were cited in the NE literature. Overall, prospective studies were rare and did not tend to reflect the highest levels of scientific evidence. There are many unanswered questions, and our understanding of the pathophysiology of NE is sparse at best. Official diagnostic criteria are also difficult to find, as are firm guidelines for treatment. Thus, the overall grade assigned to evidence in this article is low, given the virtual absence of any meaningful prospective research or clinical trials. In an editorial response by Sherwood L. Gorbach, summing up the state of our poor understanding of NE, he aptly describes the challenges of fully grasping NE thus: “the diversity of the pathology is matched by the difficulty in establishing the diagnosis on the basis of only clinical findings.” What can be said, however, is that any progress made to date, to improve outcomes in NE, has been the result of rapid identification and aggressive intervention, frequently by frontline providers such as ED physicians.

Clinical presentation and risk factors

Neutropenic patients presenting for care in the ED, after the administration of chemotherapy, represent a particularly high-acuity patient population, requiring a thoughtful and thorough evaluation for all potential sources of infection. Patients are routinely evaluated for potential sources of infection by chest radiography, complete blood counts, blood cultures, and urine analysis. Neutropenic patients, presenting with either generalized or focal abdominal pain, along with fever, should uniformly be considered at risk for NE.

Several specific chemotherapeutic agents have been implicated in the development of NE. These include, among others, taxane-based therapies (ie, paclitaxel and docetaxel), gemcitabine, cytosine arabinoside, vincristine, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin, and daunorubicin ( Box 1 ). The types of malignancies involved are also varied. Initial reports almost exclusively cited NE as a complication of pediatric leukemias. Although leukemias and many forms of lymphoma comprise a large number of the cases of NE, a wide variety of solid tumors, including breast, lung, colorectal, and ovarian cancer, have also been implicated.

Paclitaxel

Docetaxel

Gemcitabine

Cytosine

Arabinoside

Vincristine

Doxorubicin

Cyclophosphamide

5-Fluorouracil

Leucovorin

Daunorubicin

Although most patients present with NE after chemotherapeutic treatment for cancer, there are a small number of reported cases presenting in leukemic patients before the initiation of chemotherapy or as their presenting event leading to diagnosis. There is also a case report of a trauma patient who developed NE after receiving antibiotics for osteomyelitis. The underlying cause in this case was attributed to reversible neutropenia caused by nafcillin, used as part of a prolonged (>10 days) home intravenous antibiotic treatment course. Other cases have been reported in the context of AIDS, aplastic anemia, cyclic neutropenia, and immune-suppression for bone marrow transplantation or renal transplantation. Although the variety of patients at risk extends beyond the realm of oncologic patients, the unifying theme across all of these case reports is the existence of absolute neutropenia. The onset of symptoms seems to be closely related to the nadir in the patient’s white blood cell count. It is critical that the evaluating physician remain vigilant and consider NE in any neutropenic patient and not only in oncologic patients. Important nononcologic causes of NE are summarized in Box 2 .

AIDS

Nafcillin in the treatment of osteomyelitis

Aplastic anemia

Cyclic neutropenia

Bone marrow suppression for bone marrow or renal transplantation

Presenting abdominal signs and symptoms for patients with NE can be varied and elusive. Although many will present with high-grade fevers, their neutropenic state may make it more difficult for them to accurately localize infection. Many patients present with vague cramp-like abdominal pain, vomiting, and diarrhea. Right lower quadrant pain may be part of the presentation, with or without rebound tenderness. Abdominal distension and peritoneal signs may be the harbinger of intestinal perforation. The process seems to have a predilection for the terminal ileum and cecum (hence the name ileocecal syndrome or typhlitis). This is postulated to be because of the distensibility of the cecum and its limited blood supply. Common presenting signs and symptoms are summarized in Box 3 .

Vague cramp-like abdominal pain

Localized right lower quadrant abdominal pain

Abdominal distension

Diarrhea

Rebound tenderness may or may not be present

In the face of neutropenia and concurrent direct chemotherapeutic damage to the intestinal mucosa, there is an alteration of the gut lining making it more vulnerable to bacterial invasion. NE may mimic the presentation of appendicitis and a host of other diagnostic possibilities, including colonic pseudo-obstruction, inflammatory bowel disease, pseudomembranous colitis, infectious colitis, and diverticulitis.

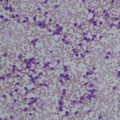

Compromise of the intestinal mucosa leaves it vulnerable to invasion by a host of pathogenic bacteria. The subsequent production of endotoxins leads to bacteremia, necrosis, and hemorrhage. Organisms isolated from surgical specimens have included gram-negative rods, gram-positive cocci, clostridial species, enterococci, cytomegalovirus, Candida species, and Clostridium difficile . These organisms may present alone or in combination. There are no data describing the discrete microbiology of NE or the combinations of pathogens associated with the presentations of NE. Organisms associated with cases of NE will reflect local patterns noted among other neutropenic patients in a given locale.

Considerations in the pediatric population closely mirror those in the adult population. A recent study by McCarville and colleagues attempting to characterize typhlitis in childhood cancer notes many of the same uncertainties of a largely clinical diagnosis based on a variable triad of fever, neutropenia, and abdominal pain. They did note that patients older than 16 years were at greater risk for typhlitis than younger patients.

Clinical presentation and risk factors

Neutropenic patients presenting for care in the ED, after the administration of chemotherapy, represent a particularly high-acuity patient population, requiring a thoughtful and thorough evaluation for all potential sources of infection. Patients are routinely evaluated for potential sources of infection by chest radiography, complete blood counts, blood cultures, and urine analysis. Neutropenic patients, presenting with either generalized or focal abdominal pain, along with fever, should uniformly be considered at risk for NE.

Several specific chemotherapeutic agents have been implicated in the development of NE. These include, among others, taxane-based therapies (ie, paclitaxel and docetaxel), gemcitabine, cytosine arabinoside, vincristine, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin, and daunorubicin ( Box 1 ). The types of malignancies involved are also varied. Initial reports almost exclusively cited NE as a complication of pediatric leukemias. Although leukemias and many forms of lymphoma comprise a large number of the cases of NE, a wide variety of solid tumors, including breast, lung, colorectal, and ovarian cancer, have also been implicated.