Neurologic manifestations are common in blood diseases, and they can be caused by the hematologic disorder or its treatment. This article discusses hematologic diseases in adult patients, and categorizes them into benign and malignant conditions. The more common benign hematologic diseases associated with neurologic manifestations include anemias, particularly caused by B 12 deficiency and sickle cell disease, and a variety of disorders of hemostasis causing bleeding or thrombosis, including thrombotic microangiopathy. Malignant conditions like multiple myeloma, leukemias, and lymphomas can have neurologic complications resulting from direct involvement, or caused by the different therapies to treat these cancers.

Key points

- •

Neurologic manifestations are common in both benign and malignant disorders, and they can affect both central and peripheral nervous system.

- •

The most common neurologic manifestations in blood cell dyscrasias are those involving the peripheral nervous system.

- •

Anemias, particularly B 12 deficiency and sickle cell disease, lymphomas, leukemias and myelomas are the diseases more frequently associated with neurological manifestations.

Introduction

Neurologic manifestations are common in blood diseases, and they can be caused by the hematologic disorder or its treatment.

This article discusses hematologic diseases in adult patients, and categorizes them into benign and malignant conditions. The more common benign hematologic diseases associated with neurologic manifestations include anemias, particularly caused by B 12 deficiency and sickle cell disease, and a variety of disorders of hemostasis causing bleeding or thrombosis, including thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA). Malignant conditions like multiple myeloma (MM), leukemias, and lymphomas can have neurologic complications resulting from direct involvement, or caused by the different therapies to treat these cancers.

A classification of the most important hematologic conditions associated with neurologic complications or manifestations is presented in Box 1 . This article gives a brief overview of these conditions, because they are developed in depth throughout this issue.

Benign hematologic conditions:

- 1.

Anemias:

- a.

B 12 deficiency, folate deficiency

- b.

Sickle cell disease

- c.

Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria

- a.

- 2.

Disorders of hemostasis:

- a.

Hemorrhagic disorders: hemophilia A and B, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), thrombocytopenias, and disorders of platelet function

- b.

Thrombotic disorders: antiphospholipid antibodies, inherited thrombophilia (eg, antithrombin III, protein C or S deficiency, factor V Leiden)

- c.

Other: thrombotic microangiopathies (eg, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, hemolytic-uremic syndrome)

DIC

- a.

Malignant hematologic conditions:

- 1.

Leukemia

- 2.

Lymphoma

- 3.

Myeloma

- 4.

Treatment of hematologic conditions

Introduction

Neurologic manifestations are common in blood diseases, and they can be caused by the hematologic disorder or its treatment.

This article discusses hematologic diseases in adult patients, and categorizes them into benign and malignant conditions. The more common benign hematologic diseases associated with neurologic manifestations include anemias, particularly caused by B 12 deficiency and sickle cell disease, and a variety of disorders of hemostasis causing bleeding or thrombosis, including thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA). Malignant conditions like multiple myeloma (MM), leukemias, and lymphomas can have neurologic complications resulting from direct involvement, or caused by the different therapies to treat these cancers.

A classification of the most important hematologic conditions associated with neurologic complications or manifestations is presented in Box 1 . This article gives a brief overview of these conditions, because they are developed in depth throughout this issue.

Benign hematologic conditions:

- 1.

Anemias:

- a.

B 12 deficiency, folate deficiency

- b.

Sickle cell disease

- c.

Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria

- a.

- 2.

Disorders of hemostasis:

- a.

Hemorrhagic disorders: hemophilia A and B, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), thrombocytopenias, and disorders of platelet function

- b.

Thrombotic disorders: antiphospholipid antibodies, inherited thrombophilia (eg, antithrombin III, protein C or S deficiency, factor V Leiden)

- c.

Other: thrombotic microangiopathies (eg, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, hemolytic-uremic syndrome)

DIC

- a.

Malignant hematologic conditions:

- 1.

Leukemia

- 2.

Lymphoma

- 3.

Myeloma

- 4.

Treatment of hematologic conditions

Benign hematologic conditions

Anemias

Iron deficiency anemias are frequently associated with nonspecific symptoms like fatigue, weakness, irritability, dizziness, tinnitus, and headache. Pseudotumor cerebri and cerebral venous sinus thrombosis have also been associated with iron deficiency. However, thrombotic episodes are likely to be associated with the thrombocytosis that occurs in iron-deficient patients; this can sometimes be severe and cause cerebrovascular infarction or transient ischemic attacks (TIAs). In patients with preexisting severe vascular disease, anemia can contribute to cerebrovascular or cardiac events that usually reverse with an increase in hemoglobin.

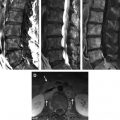

Vitamin B 12 deficiency can cause neurologic symptoms even in the absence of appreciable alterations in peripheral blood and with normoblastic hematopoiesis. Furthermore, the size of the red cells can be within normal limits, because some of these patients have coexisting iron deficiency. Thus, methylmalonic acid and total homocysteine levels may be useful adjuncts in the diagnosis. Sensory peripheral neuropathy and myelopathy can occur because of loss of large, myelinated fibers, and axonal degeneration. Neuropathy usually has upper-limb onset and associated Lhermitte phenomenon. Myelopathy is accompanied by early and severe impairment of proprioception and vibration sense. Other less common forms of neurologic involvement, like sensory ataxic spastic paraparesis and optic neuropathy, have also been described. Encephalopathy with unspecified mental status changes or affective disorders have been found in about 20% of patients with B 12 deficiency. Folate deficiency is a more common cause of neurologic disease in children, in whom it typically presents with seizures, delayed motor and cognitive development, cerebellar ataxia, spasticity, and visual and hearing impairment. Subacute combined degeneration of the cord accompanying diet-induced folic acid deficiency may occur and can improve with replacement.

Sickle cell disease is a frequent cause of neurologic symptoms, and about 25% of patients have some form of neurologic manifestation, most frequently cerebral infarction. Intracranial hemorrhage is much rarer, and usually subarachnoid and aneurysmal in cause.

Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) is a stem cell disorder caused by mutations in the phosphatidylinositol glycan class A gene. This mutation results in a deficiency in the binding of several proteins that protect red cells from complement-induced hemolysis. Hemolysis is intravascular, and it occurs in the setting of hypercoagulability, which in these patients is multifactorial. The most common manifestation of this hypercoagulable state is large-vessel venous thrombosis, particularly in the brain and portal systems. Furthermore, a neurologic cause of death can be found in 10% of patients with PNH, including cerebral venous thrombosis, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and intracerebral hemorrhage.

Disorders of Hemostasis

Hemorrhagic disorders

Hemophilias A and B have identical neurologic manifestations, which happen in the most severe forms of the disease. Peripheral nerve lesions are the most common complication, and they are usually related to muscular or joint bleeding. The iliac muscle is commonly involved, leading to femoral neuropathy. Severe hemophilic arthropathy of the elbow can sometimes lead to ulnar nerve palsy. Intracranial hemorrhage occurs in 2% to 14% of patients, and is the leading cause of death in these patients. Bleeding usually occurs in younger patients, and it can be subdural, epidural, subarachnoid, or intracerebral.

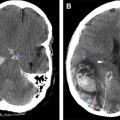

Thrombocytopenias can lead to subdural, subarachnoid, and intracerebral bleeding, particularly during the first 2 weeks of onset, and at a platelet count of less than 20 × 10 9 /L. A special case and the most frequent cause of drug-induced immune thrombocytopenia, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, is paradoxically associated with thrombosis, including ischemic damage to limbs, central nervous system (CNS), myocardium, and lungs in up to 60% of cases. Abnormal bleeding can result from disorders of platelet function, including adhesion, aggregation, secretion, and procoagulant activity. The most common causes are drug related, including aspirin, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, and ticlopidine.

Thrombotic disorders

Thrombosis may arise from abnormalities in the blood vessel wall, alterations in blood composition, and abnormalities in the dynamics of blood flow; the triad of Virchow. The list of well-recognized prothrombotic circumstances is extensive, and beyond the scope of this article. Thus, the focus here is on general aspects of the more common acquired and inherited disorders with neurologic manifestations.

The lupus anticoagulant and anticardiolipin are members of a group of antiphospholipid antibodies associated with venous and, to a lesser extent, arterial thrombosis. A diagnosis requires the combination of at least 1 clinical and 1 laboratory criterion that persist over time. In patients with lupus, predisposition to thrombosis is associated with antinuclear antibodies and antiphospholipid antibodies. The primary antiphospholipid syndrome is the association between arterial and venous thrombosis with the lupus anticoagulant, phospholipid antibodies, and a history of recurrent early miscarriage. Neurologic manifestations are common, and include migraine (20.2%), stroke (19.8%), TIA (11.1%), epilepsy (7%), amaurosis fugax (5.4%), and less frequently vascular dementia, transient amnesia, chorea, acute encephalopathy, optic neuritis, retinal artery thrombosis, cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, cerebellar ataxia, transverse myelopathy, and hemiballismus.

Inherited thrombophilias are a group of disorders with a defect or deficiency in the natural anticoagulant mechanisms that predisposes to the development of venous thrombosis. A genetic factor is identified in up to 50% of unselected patients with venous thromboembolism, and genetic or acquired factors in 80% of patients with cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. Antithrombin III, protein C, and protein S deficiencies; factor V Leiden mutations; the prothrombin G20210A gene mutation; and MTHFR C677T mutations (resulting in hyperhomocysteinemia) all predispose to thrombosis. Antithrombin III, protein C, and protein S deficiencies are rare, but pose the highest risk, with highly penetrant phenotypes that can lead to a 10-fold increase in risk for heterozygous carriers.

Thrombotic microangiopathies

Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) is a severe form of TMA that results from excessive systemic platelet aggregation caused by the accumulation of unfolded high-molecular-weight von Willebrand factor multimers in plasma. This failure to process von Willebrand factor into less adhesive forms is related to severe deficiency of ADAMTS13, a von Willebrand factor protease. TTP can be inherited or acquired, occurs most frequently in women between 20 and 50 years of age, and can have a high fatality rate depending on the cause and severity of the syndrome. Acquired cases are more frequently associated with pregnancy, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, infection, and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). Neurologic features are the most common presenting manifestations in TTP, occurring in about 60% of patients. As the result of involvement of any part of the CNS, there is a large variety of neurologic manifestations, typically transient and fluctuating, and frequently resembling a TIA. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome is the most frequent brain imaging abnormality, along with microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, hyperbilirubinemia, uremia, and bone marrow hyperplasia. Hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS), is the other form of TMA, typically presenting in children with a recent infection by organisms producing Shiga toxins such as Escherichia coli O157:H7 or Shigella. Therefore, diarrhea and abdominal pain frequently precede the onset of HUS. Deficiency of ADAMTS13 has not been shown in HUS, and, unlike TTP, most children survive with just supportive care. The most common neurologic manifestations are seizures, but behavioral changes and cerebral, cerebellar, and brainstem syndromes can occur.

Disseminated intravascular coagulation

DIC should be considered an indication of the presence of an underlying disorder, and a manifestation of inappropriate thrombin activation. The coagulation system is activated by the rapid release of thromboplastic substances resulting in the production of fibrin. Clotting factors and platelets are consumed, and there is defective and activated fibrinolysis and impairment of the coagulation inhibition system. The clinical syndrome results from vascular obstruction from fibrin-rich thrombi. In contrast, the overwhelming consumption of alpha 2 -antiplasmin and platelets, along with the anticoagulant properties of fibrin degradation products, can also result in bleeding. The list of causes that can lead to DIC is extensive, including tissue damage caused by burns, heat stroke, status epilepticus, severe infection, obstetric complications, and diabetic ketoacidosis. When the CNS is affected, the neurologic manifestations of DIC depend on the degree and location of the thrombotic and hemorrhagic events, as well as the primary disorder that triggered it. Any part of the brain can be affected, causing focal or generalized encephalopathic manifestations that can fluctuate markedly over time.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree