PEARLS

❖ Parkinson disease is the number one neurologic disease in older adults, and the most common symptoms of Parkinson disease are slowness with activities of daily living, shuffling, tremor, difficulty with speech, and erratic movements.

❖ When assessing and treating patients with Parkinson disease, it is imperative to thoroughly assess and discriminate among direct, indirect, and composite impairments when designing treatment interventions.

❖ Patients with Parkinson disease may respond to a specific evaluation and treatment progression of exercise and gait programs.

❖ Numerous methods exist for assessing older patients with strokes. Therapists should choose tools that have the greatest functional emphasis and applicability to geriatric rehabilitation.

❖ Treatment strategies for patients with stroke are varied, and some are modified for older adults.

❖ Exercise should consist of functionally oriented activities in the Alzheimer population.

❖ The maintenance of posture and the ability to move about the environment depend on orientation and balance, and the postural control system receives information from receptors in the proprioceptive, visual, and vestibular systems.

This chapter builds on the discussion of specific biological changes that occur with age or pathology as developed in Chapters 3 and 5. This chapter discusses a model for looking at neurologic dysfunction followed by sections on mobility, balance and coordination, weakness, and tremor. The major pathologies discussed are Parkinson disease (PD) and cerebrovascular accidents (CVAs), which are discussed in terms of prevalence, efficacy of treatment interventions, evaluation, and treatment strategies. This is followed by a discussion of the evaluation and treatment of the common neurologic pathology, Alzheimer disease (AD), which requires special consideration. The last section of this chapter focuses on balance and falls, evaluation of the numerous causes of dizziness and physical changes that increase the risk of falling, and treatment interventions aimed at decreasing the incidence of falls.

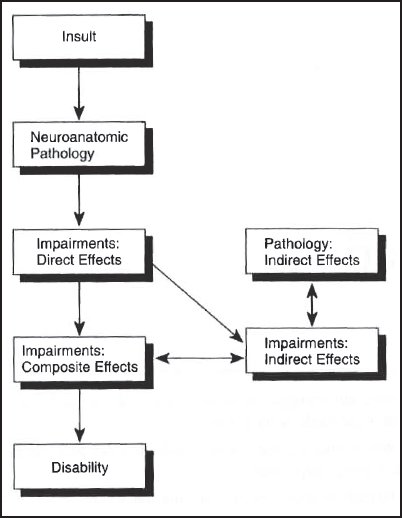

The model for neurologic dysfunction used is that of Schenkman and Butler.1 Figure 12-1 illustrates the progression of the stages that result in ultimate disability. In geriatric rehabilitation, many of the problems or impairments/disorders associated with neurologic dysfunction/insults, including balance problems and frailty, have multiple causes as a result of multisystem involvement. The Schenkman and Butler model provides a guide for a problem-solving approach to identify the underlying causes of neurologic dysfunction. The use of this model substantially improves the effective evaluation and treatment of medically complex patients with neurologic pathology.1,2 This model is best explained using an example; therefore, a patient with a CVA in which the neuroanatomic pathology is a parietal lobe lesion is discussed. The impairment’s direct effects might include a motor loss from the parietal lesion, resulting in hypotonicity of the shoulder. An indirect pathological effect could be a rotator cuff tear, and the resulting impairment would be a subluxed shoulder. The impairment’s composite effects would be a decreased use of the upper extremity and pain on movement as well as movement dysfunction in the upper and lower extremities. The resultant functional disability is the patient’s inability to dress or walk independently or sleep without discomfort.

The therapist can then use this model to examine where physical or occupational therapy can benefit the patient. In this example, the therapist may have little effect on the insult or neuroanatomical pathology, but the therapist could positively affect the other areas. Using this information, the therapist can choose the most effective intervention for the problem. This problem-solving model should be kept in mind when reviewing the subsequent dysfunctions.

Figure 12-1. An outline of a model for evaluating, interpreting, and treating individuals with neurologic dysfunction. (Reprinted with permission from Schenkman B, Butler RB. A model for multisystem evaluation, interpretation and treatment of individuals with neurologic dysfunction. Phys Ther. 1989;69[7]:538-547.)

PARKINSON DISEASE

PD is the primary neurologic disease of older adults.3 It affects 1% of people over 50 years of age, and 50,000 new cases are diagnosed annually.3 The description of PD and its causes have been covered in detail in Chapter 5. PD follows a defined clinical pattern, and a range of nonmotor symptoms precede the motor phase.3 The predominant early nonmotor manifestations are olfactory impairment and constipation.3 The most common motor symptoms in PD are the following3,4:

❖ Slowness in ambulation and dressing

❖ Difficulty in getting out of a chair and turning in bed

❖ Shuffling

❖ Stooping when walking or falling to one side when sitting

❖ Difficulty with speech

❖ Tremor and handwriting changes

❖ Difficulty initiating movements

Medical management of PD revolves mainly around the use of drugs such as L-dopa. It is important to note that the side effects associated with L-dopa’s use are less virulent in older adults, and therefore, it can be prescribed at the onset.5 The literature is filled with controversy regarding the dosage and side effects of anti-PD medications (see Chapter 7 for the side effects). The most noteworthy and deleterious side effects in older adults are mental side effects, such as disorientation and confusion.6

The medical management of PD depends on the stage of disability. The Hoehn and Yahr7 stages are as follows:

❖ Stage I is characterized by minimal or no functional impairment and unilateral involvement only.

❖ Stage II is characterized by bilateral involvement without any type of balance impairment.

❖ Stage III is characterized by mild to moderate disability; in this stage, the patient may lose righting reflexes as evidenced by unsteadiness on turns.

❖ Stage IV is characterized by moderate to severe disability. The patient can still walk and stand unassisted but is not stable.

❖ Stage V is severe disability, and in this stage, the patient is confined to bed or a wheelchair.

The medical literature has shown that medication alone is not adequate treatment for this disease and that rehabilitation therapy is an important adjunct to medical treatment.4–9

Physical therapy has been shown to be efficacious for these patients.9 In a study by Banks, patients with PD with all degrees of impairment and duration of the disease improved in walking and other mobility skills after physical therapy.9

Evaluation

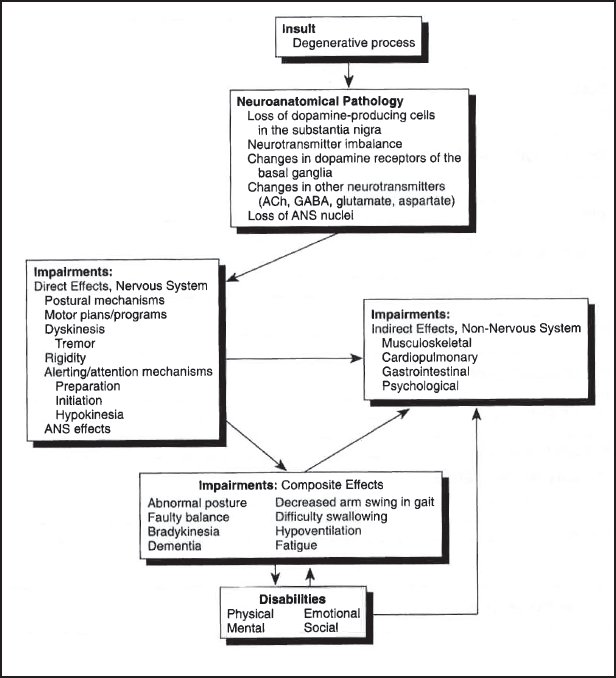

Schenkman and Butler10 have developed a model for the evaluation of patients with PD (Figure 12-2). This model can be used as a guideline for evaluating patients with PD. The therapist can begin by assessing the direct effects of the nervous system, such as tremor rigidity, hypokinesis, and autonomic nervous system effects. Although it is important to note these, it is also important to recognize that these impairments will respond less dramatically to physical therapy procedures than the indirect effect impairments.10 The indirect effect impairments are changes in the musculoskeletal system, such as flexibility, strength, and vital capacity. The combined changes of these 2 areas make up the major impairments listed in composite effects.

Figure 12-2. An overview of a model for evaluation and treatment of patients with Parkinson disease. ACh, acetylcholine; ANS, autonomic nervous system; GABA, gamma-aminobutyric acid. (Reprinted with permission from Schenkman B, Butler RB. A model for multisystem evaluation, interpretation and treatment of individuals with neurologic dysfunction. Phys Ther. 1989;69[7]:538-547.)

Evaluation Form

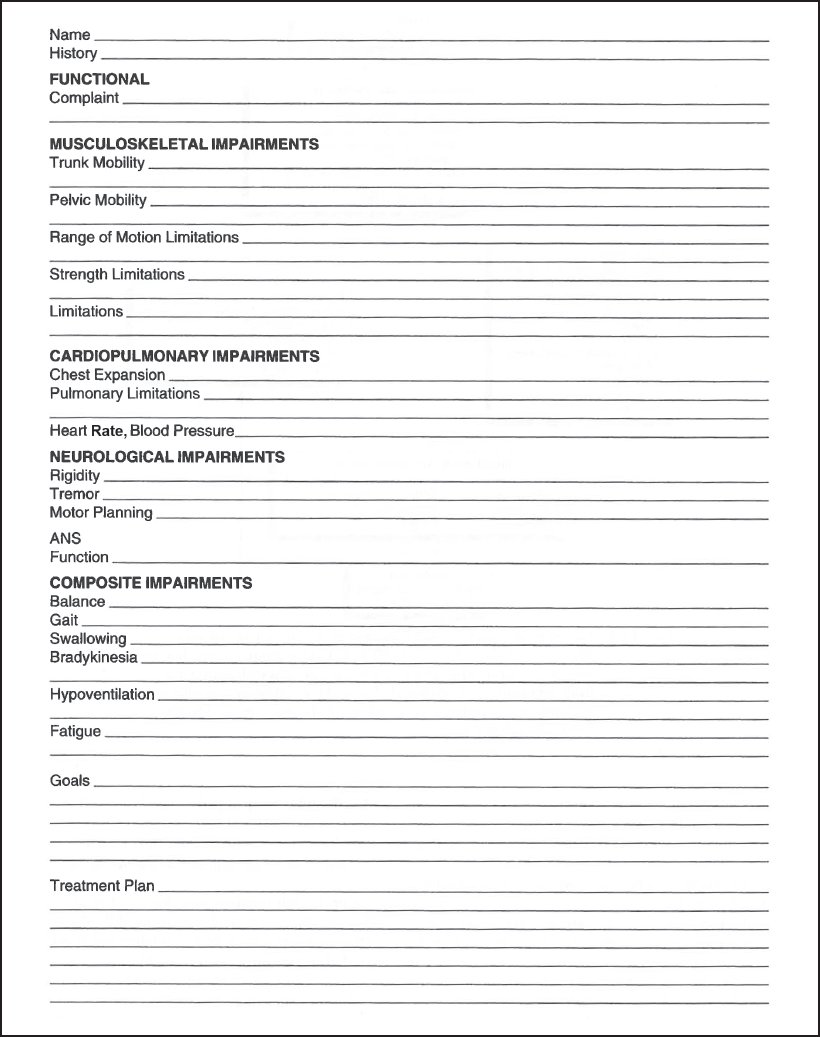

Figure 12-3 is an evaluation form that highlights and expands on the relevant impairments. This form affords the therapist the ability to differentiate between the various types of impairment.

Under the impairment categories, the therapist looks for the following:

- Musculoskeletal impairments: Trunk mobility (unilateral and then bilateral trunk limitation, increased kyphosis, and decreased lumbar extension) and pelvic mobility (decreased rotation and decreased ability to tilt the pelvis)

a. Range of motion limitations: Decreased motion in the plantar flexors, hip flexors, and neck rotators

b. Strength limitation: Weak hip extensors, dorsi/plantar flexors, and trunk extensors

c. Postural limitations: Forward head, rounded shoulders, kyphosis, and increased hip and knee flexion

- Cardiopulmonary impairments: Decreased chest expansion and increased heart rate and blood pressure

a. Slowed movements and difficulty breathing

b. Increased fatigue and orthostatic hypotension

- Neurologic impairments: Increased rigidity, resting tremor, slowness of movement, difficulty initiating movement, and increased drooling and flushing

a. Balance impairment: Increased loss of balance

b. Gait impairment: Shuffling, festination, retropulsion, no arm swing, and slow pace

c. Swallowing impairments: Increased difficulty swallowing

Even with an extremely comprehensive form such as Figure 12-3, there are still areas that require special mention. For example, tremor may be overlooked because it is only present intermittently, minimally, or in one joint. Because tremor may be difficult to assess, the therapist should have the patient sit with arms resting on legs. The patient is then instructed to count backward by 2 from 100. This activity stresses the patient and brings out the resting tremor, which the therapist can then observe. Once the therapist has observed the tremor, placing the hands over the moving part will elicit the 4- to 7-second tremor and confirm the resting tremor.11

Figure 12-3. Parkinson evaluation form. (© Carole B. Lewis.)

A good test for bradykinesia is to have the patient sit with both hands in his or her lap. The patient then supinates and pronates the forearms as rapidly as possible on one side and then the other. If the symptoms are unilateral, the therapist should start with the uninvolved side. The patient must do this activity for at least 20 seconds with the therapist observing for quality of movement. There may be no noticeable impairment at first; however, after 3 to 4 seconds, the patient will begin to substitute by shortening the arc or will fail to flip hands over completely, and movement will generally slow. If this is noted, bradykinesia is confirmed.11

Hand posture can be checked by standing above and behind the patient, grasping both wrists, and shaking both hands up and down. The therapist observes for looseness and thumb position. If the patient fails to show general looseness or opposition of the thumb while shaking, this may be a sign of early-stage involvement. As the disease progresses, the patient will display finger adduction and flexion of the metacarpals, interphalangeal extension, and ulnar deviation. In the very advanced stages, the wrist may be drawn into flexion and pronation.11

Rigidity should be assessed in the neck, trunk, and all of the extremities. Assessment for rigidity simply involves moving the part through the range of motion, making sure the patient is relaxed and not tensing the muscles. The therapist then notes any resistance or tension. All normal muscle movements should float.11

Weinrich and associates12 noted that limitations in the wrist and head in axial rotation were related to the improvement of symptoms of PD. Therefore, this measure may be an important tool in assessment.

Gait Evaluation

Gait changes in patients with PD deserve special mention. There are significant changes in parkinsonian gait compared to the normal gait.13 These changes are as follows:

❖ Decreased step length

❖ Wider stride width

❖ Increased knee flexion in the standing position (normally, 3 degrees of hyperextension at the knee is observed in standing; patients with PD tend to stand in 3, 6, and 12 degrees of flexion for groups with mild, moderate, and severe disabilities, respectively)

❖ Decreased mean total amplitude for flexion/extension used during free walking (degrees respectively in patients with PD and disabilities)13

❖ Simultaneous thoracic and pelvic rotation in free speed walking

❖ Decreased heel floor angle at heel strike (norms 21 to 16 degrees, 11 to 6 degrees for patients with PD)13

Functional Assessment

A final area of evaluation of the patient with PD is functional assessment. In a study by Henderson and associates,14 functional or activities of daily living (ADLs) assessments were shown to be good for assessing functional deficits. However, the study did find that if a description of the disease were sought, then an assessment of the actual signs of the disease would be better.14

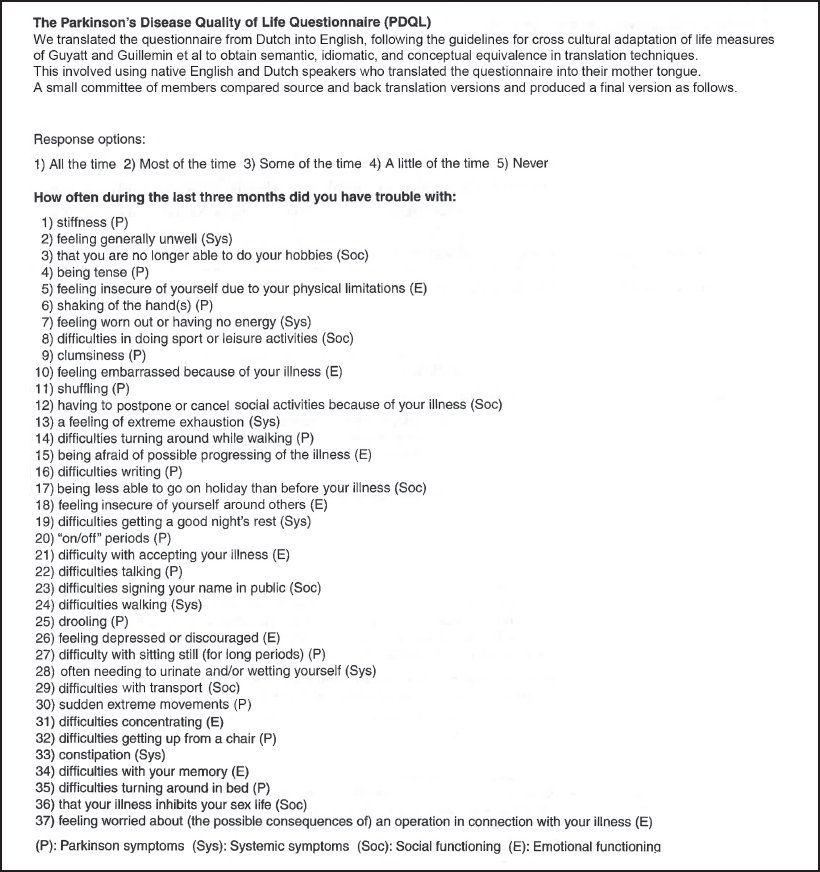

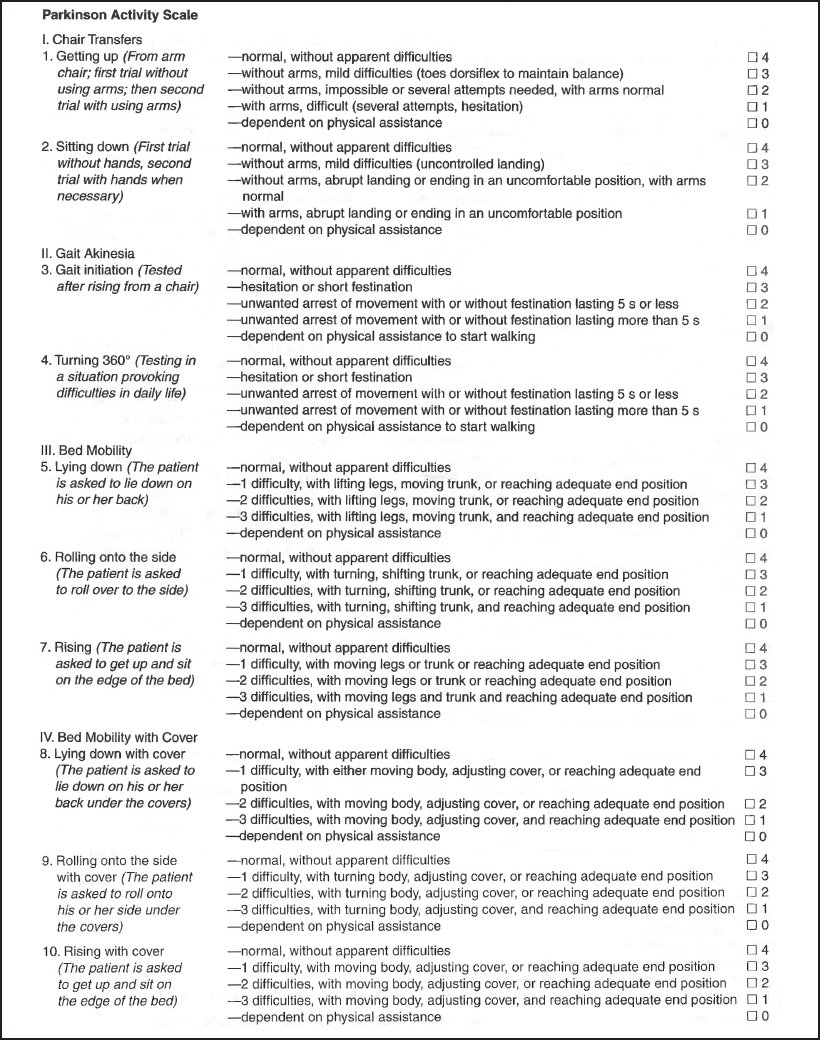

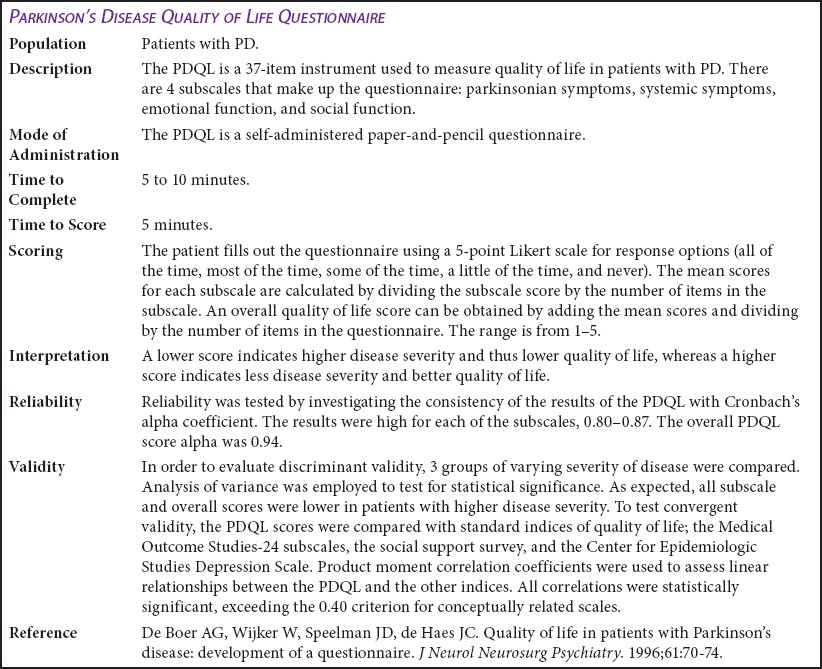

Two ratings scales that incorporate both signs and ADL assessment are found in Table 12-1 and Figure 12-4.11,15 Once the therapist has conducted a thorough evaluation, then the treatment can be initiated. See Appendix A for evidence-based evaluation ideas.

Treatment Considerations

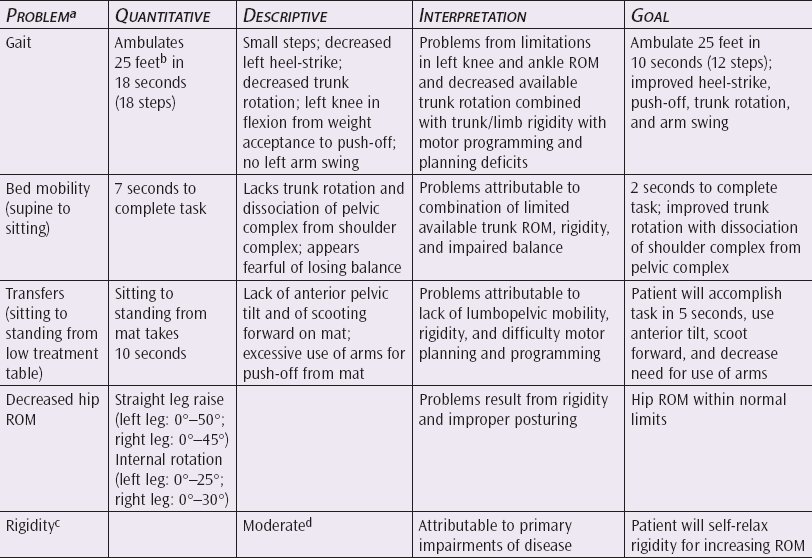

When designing a treatment program for patients with PD, the model of Schenkman and coauthors16 can be useful. The therapist must keep in mind which deficits can be corrected and which respond minimally to physical therapy. Rigidity, for example, may be temporarily relaxed in order to facilitate muscle stretching. However, the permanent effects of relaxation training on muscle rigidity will be minimal.17 Therefore, prior to initiating a program, the therapist must prioritize the problems and interpret the goals in terms of what is efficacious. Table 12-2 is an example of this process.16

Schenkman’s Approach

Schenkman suggests the following treatment progression16:

❖ Relaxation

❖ Breathing exercises

❖ Passive muscle stretching and positioning

❖ Active range of motion and postural alignment

❖ Weight shifting

❖ Balance responses

❖ Gait activities

❖ Patient home exercises

Table 12-1. Parkinson Disease Rating Scale

Reprinted with permission from Webster D. Critical analysis of the disability in Parkinson’s disease. Mod Treat. 1969;5:257-282.

As mentioned previously, relaxation can be used to temporarily decrease rigidity and increase flexibility. Relaxation of the muscles can be induced by slow rhythmic rotating movements beginning with very small motions and progressing to larger ones. Other techniques, such as biofeedback, contract-relax stretch, and deep breathing, can be helpful. The relaxation will be more effective if the approach begins in the supine position and progresses to sitting and standing; the more supported the individual is, the better the ability to relax will be. In addition, relaxation is better if it is begun passively and is progressed to active. Finally, the relaxation is more effective if the patient is taught to relax individual functional segments (eg, the head on the thorax, the shoulder on the thorax, and the lower extremity on the pelvis).

Breathing or breathing control should be encouraged throughout the various stages of treatment. The patient is taught to take deep relaxed breaths while doing the relaxation exercises. Once the patient has achieved some degree of relaxation in the thoracic area, then deeper breathing combined with trunk stretching can help to increase chest expansion.

Passive muscle stretching is another commonly used modality for physical therapy. What is different for the patient with PD is the mode and area of application. As with relaxation, the most effective stretch will be with the body in the most supported position due to the patient’s decreased protective responses; therefore, begin with stretching in the supine or side-lying position. Areas requiring special stretching are the following:

❖ Lumbopelvic extensions for balance

❖ Rotation and lateral flexion of the pelvis

❖ Hamstring and plantar flexion

❖ Cervical and thoracic extension rotation and lateral flexion

❖ Hip extension, external rotation, and abduction

❖ Elbow extension and supination

❖ Finger flexion and extension

To achieve passive stretching, contract-relax stretching and passive stretching using 15- to 30-second stretches give the best results.18 Stretching is followed by active range of motion and postural alignment.

Figure 12-4A. Parkinson’s Disease Quality of Life Questionnaire.

The key to achieving the best results in active range of motion and postural alignment is repetition. For a movement to become assimilated by the nervous system, it needs millions of repetitions, which equates to hundreds to thousands of repetitions a day.19 Therefore, the patient should do the activity for 5 to 10 minutes instead of 5 to 10 times. Some of the most useful active motion activities for these areas are (1) pelvic clocks to enhance pelvic and lumbar motion, (2) isolated lateral and anterior pelvic tilts, and (3) clocks around any joint in the body. If the patient has limitation in the lumbar spine, the patient may substitute pelvic-femoral motion for lumbopelvic motion. Therefore, evaluate and treat any loss of mobility in the lumbar spine.

Once the patient is able to actively move the various body parts in a supine position and then a standing position following stretching, then weight shifting in a standing position with the pelvis in a balanced position is practiced. Weight shifting, like the previous sequences, can be practiced from the supine to the standing positions.

Finally, balance activities and responses must be stressed. Here the patient’s balance can be challenged intrinsically and extrinsically. Methods of challenging the patient’s intrinsic balance include having the patient reach overhead, from side to side, and backward in a rotational direction when sitting and standing. For extrinsic balance challenges, the therapist can apply an outside stress, such as a gentle shove, to disturb the patient’s balance. Both are needed for everyday activity and should be practiced when sitting and standing.

Function is the final area of treatment and must always be kept in mind when designing the exercise program because exercises are most effective if they relate to function. For example, trunk rotation should be followed by rolling in bed as an active functional activity that the patient can do on his or her own at home. Anterior pelvic tilting when standing is another useful home exercise employing a needed functional activity. When designing a home exercise program, be sure to stress the functional carryover. This way when the patient does daily activities, he or she is constantly doing the exercise program.

Flewitt-Handford Exercises

Another well-known program for patients with PD are the Flewitt-Handford exercises. These exercises were developed to help improve the gait of these patients. The developers of the exercises believe that the gait seen is a result of adaption to gain control of forward progression and balance. Patients with PD have plenty of propulsion, but they lack a braking mechanism. Flewitt-Handford exercises are directed to reteach heel strike, improve weight transference, increase motion of the hip and knee, and prevent stiffness of the lower extremity (Table 12-3).20

Patient education is an important component for the treatment of the patient with PD. The Parkinson’s Disease Foundation is an excellent resource for information and assistance for the patient and the families. It has developed an exercise videotape for patients with PD called Get-up and Go, which is a useful tool for helping patients maintain the benefits of a rehabilitation program in a fun and interesting way.

Group Rehabilitation

Another treatment consideration is group rehabilitation.21 Table 12-4 is a sample group evaluation and exercise progression. See Appendix A for evidence-based treatment ideas.

Table 12-4. Parkinsonism Evaluation

Republished with permission of the American Occupational Therapy Association, from Team management of Parkinson’s disease, Davis J, Am J Occup Ther, 31, 1977; permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.

STROKE

Even though stroke is not the major neurologic problem of old age, it is significant because it is such a functionally devastating disease. In the United States alone, between 250,000 and 300,000 persons have CVAs a year.22,23 Most strokes occur late in life; 43% percent of patients who have sustained a stroke are over the age of 74.23,24

In absolute numbers, women and men over age 75 are almost equally afflicted with CVAs; however, because the ratio of women to men is so much greater (3:2), statistically men have a greater likelihood of developing stroke.25 Black and Japanese American persons are more likely to have strokes than white persons, and the geographic area with the highest percentage of strokes is the southern United States.23,26

Besides causing tremendous morbidity (it is estimated that 20% to 40% of patients with stroke die within 30 days),27 nearly 40% of people with this disease report limitations in their activities. Cerebrovascular disease results in an average of 36 days of restricted activity for stroke victims.28

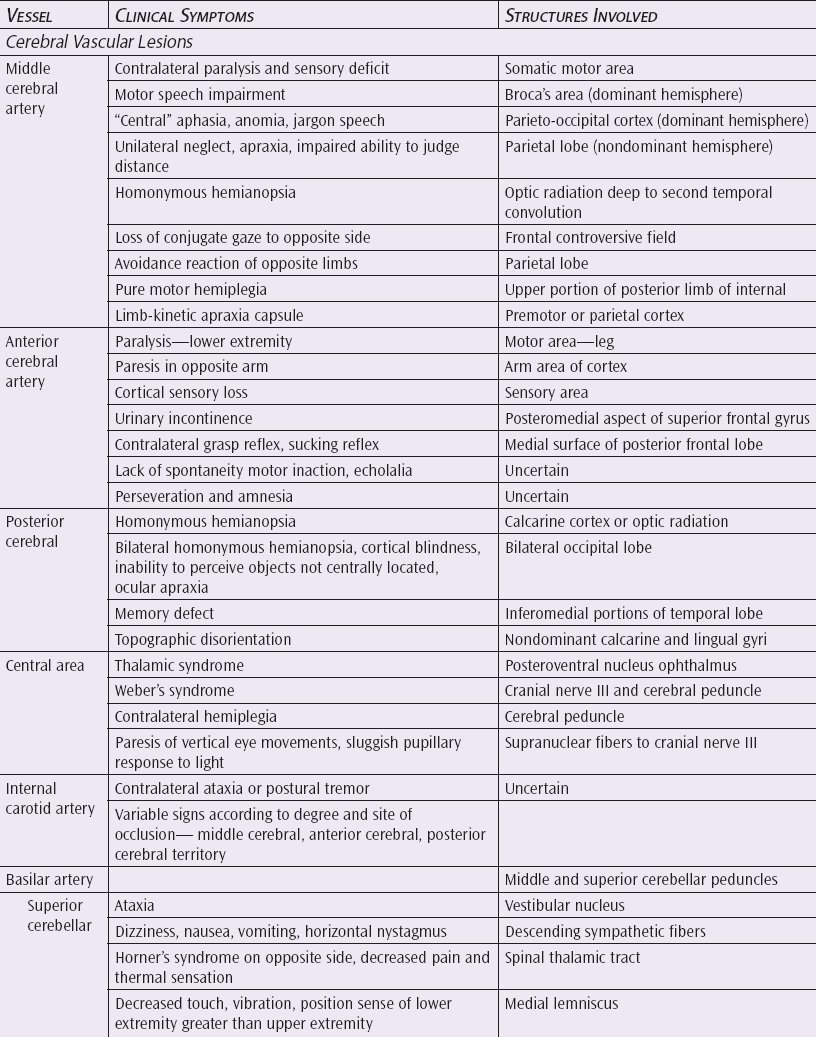

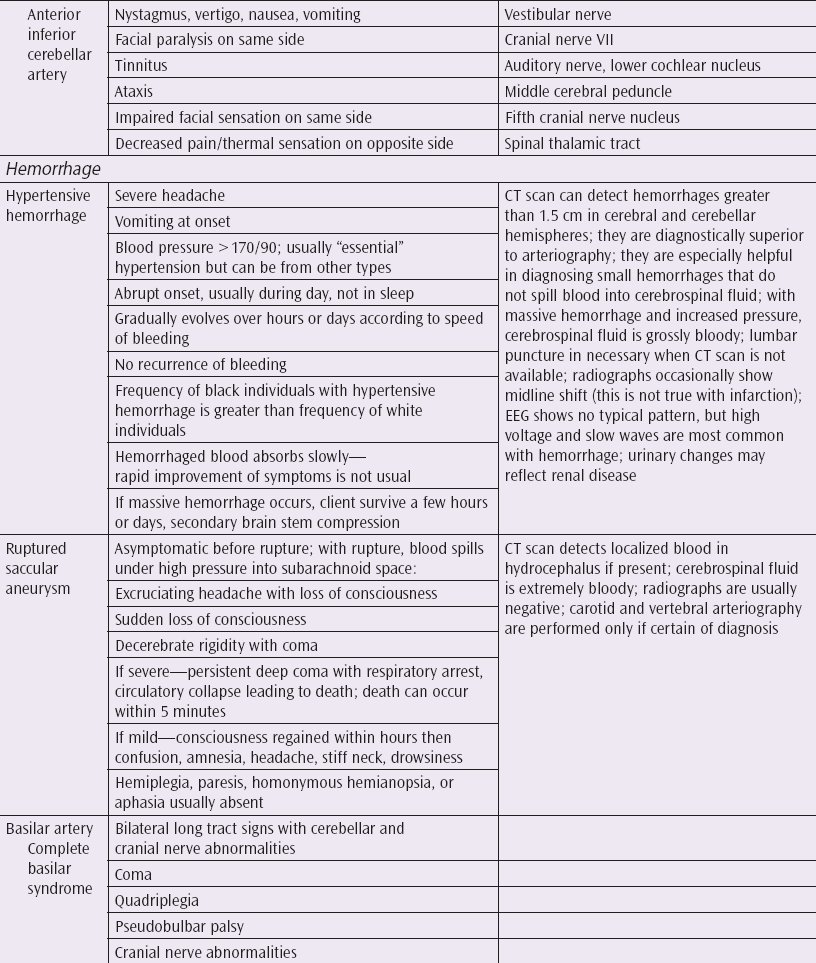

There are 3 major types of strokes. Cerebral thrombosis occurs when an artery that supplies blood to the brain becomes narrowed by plaque and deposits. The blood may coagulate and form a clot that does not allow sufficient blood through to the area. Cerebral emboli is caused by a blockage of some foreign object in the bloodstream, such as a clot, that can become wedged where it obstructs blood flow to the brain. The final type of stroke is cerebral hemorrhage in which the artery is not blocked but bursts and blood seeps into the surrounding brain tissue. Depending on the extent of the damage, cerebral hemorrhage is usually the most severe type of stroke followed by thrombosis and then emboli. The severity of the stroke also depends on what area of the brain is affected and the extent and duration of the blockage of blood. Table 12-5 shows the clinical symptoms of vascular lesions and neurovascular disease.29

Risk factors associated with stroke are similar for young and old. Such factors as previous cerebrovascular disease, taking certain prescribed medicines, and regular cigarette smoking are classified as high-risk factors. Family history is also a factor but is not found to be significant in the older population.23,30

Perceptual deficits occur in varying degrees with a stroke. Table 12-6 is a chart of these deficits.

A central problem in tone occurs in approximately 10% of patients who have sustained a stroke. This condition, which severely affects gait and balance in the hemiplegic, has been termed Pusher syndrome.31 This problem is one of postural imbalance due to ipsilateral pushing or lateropulsion. The patient pushes strongly away from the unaffected side toward the hemiplegic side. Ipsilateral pushing varies in severity from mild to severe and may be transient or pronounced and prolonged.32 If severe, pushing occurs in all positions (supine, sitting, and standing), and during remission or resolution, pushing typically disappears first in the supine position, then in the sitting position, and finally in the standing position. Pushing increases in intensity with the difficulty of the postural challenge.33 The most apparent problem of this syndrome is that it represents a threat to safety during standing and transfers as the hemiside cannot effectively support body weight.

It has been suggested that the damage from the stroke lesion occurs in the subcortical sensory pathways.32,33 Pusher syndrome affects sensory feedback in relationship to posture and gravity, leading to a misperception of the individual’s position in space. In other words, the patient reflexively compensates for a false feeling of leaning toward the unaffected side by leaning in the opposite direction.31

Before a therapist can begin evaluating and treating a patient with stroke, a thorough understanding of the various stages of recovery of limb tone is essential. In the majority of cases, the predominant abnormality on admission in both the upper and lower extremity is flaccidity.34 The recovery of tone goes through stages of progression occurring mainly in the first 7 to 14 days. By day 28, a total of 20% of the patients had normal upper limb tone, and 28% of the patients had normal lower limb tone.34

Many of the following evaluative techniques are for assessing tone. It is imperative to realize that the greatest recovery occurs within the first 7 days, and many patients do regain spontaneous motor recovery within that time. Studies as of yet have not shown a difference in this early recovery stage between young and old.34

The efficacy of rehabilitation techniques for patients with stroke has been questioned by legislative as well as administrative personnel. Nevertheless, there are several references that point to the efficacy of physical therapy.35–37 There are excellent improvements for patients with stroke over the age of 80 who are discharged to the home for up to 2 years.38 Longitudinal studies are needed to determine the long-term effects of rehabilitation. Older patients can improve on a stroke rehabilitation program if it is properly applied. Evaluation and treatment techniques for the older patient are described next.

Evaluation

Several models for evaluating patients who have sustained a stroke can be used. As mentioned in the PD section, Schenkman and Butler1 focus on impairments and direct and indirect effects of the disease as well as functional disability. This model stresses that there are certain areas where physical therapy will be more beneficial.

Other authors have developed extensive forms and methods of evaluating patients with stroke, and one interesting model developed by Tripp et al39 divides assessment into the following areas:

❖ Motor neuron response: Evaluates tone in terms of spasticity and ability to activate and relax muscle with associated reactions

❖ Fractionated movement: Evaluates the ability of the patient to move individual limb segments

❖ Movement consistency: Evaluates whether or not the patient’s ability to perform gross motor activities is consistent with his or her ability to form isolated movements

❖ Mental status: Looks at ability to follow commands and ability to learn safety and judgment

❖ Functional assessment: Includes mobility and gross upper extremity function39

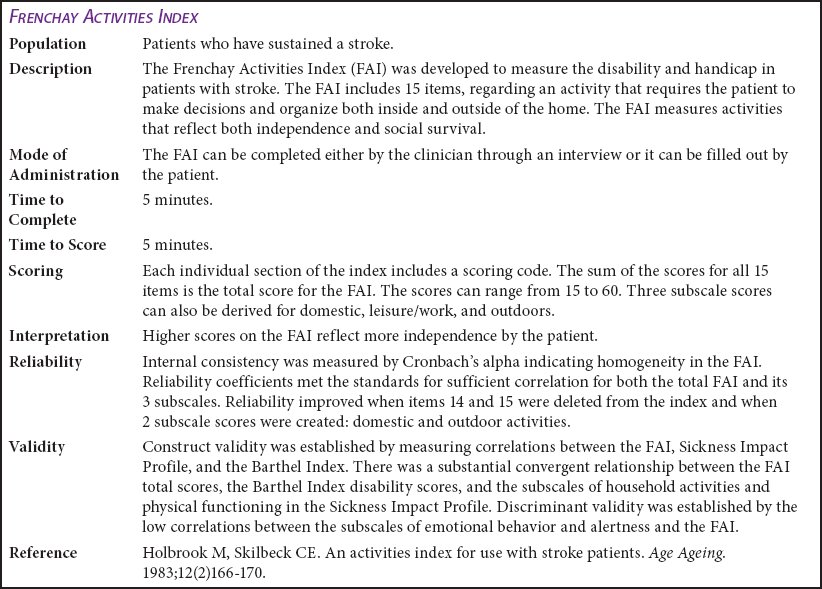

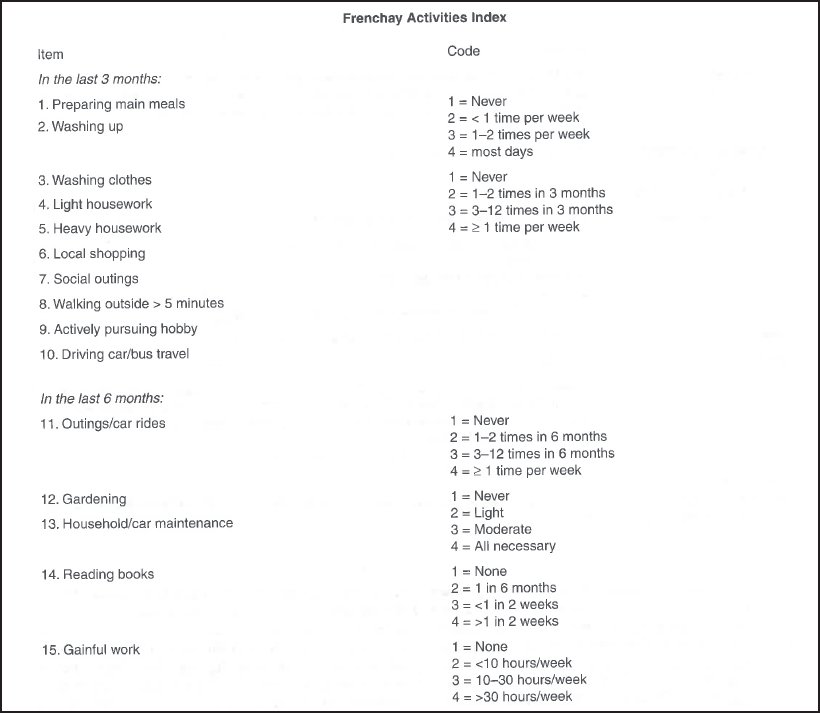

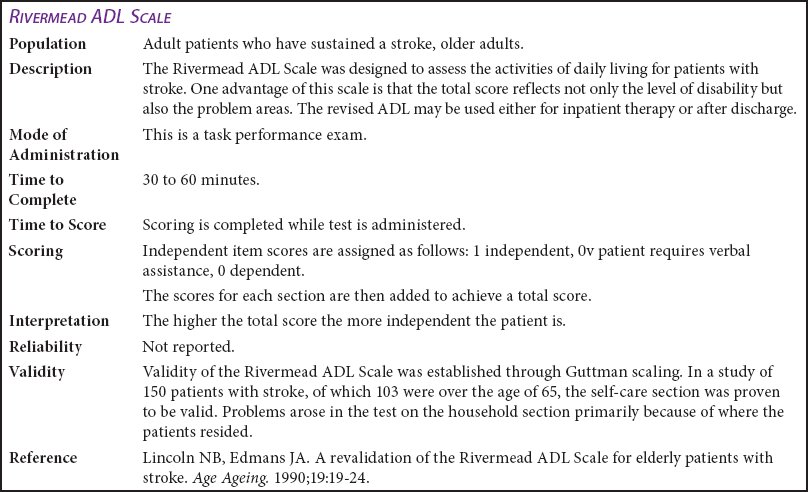

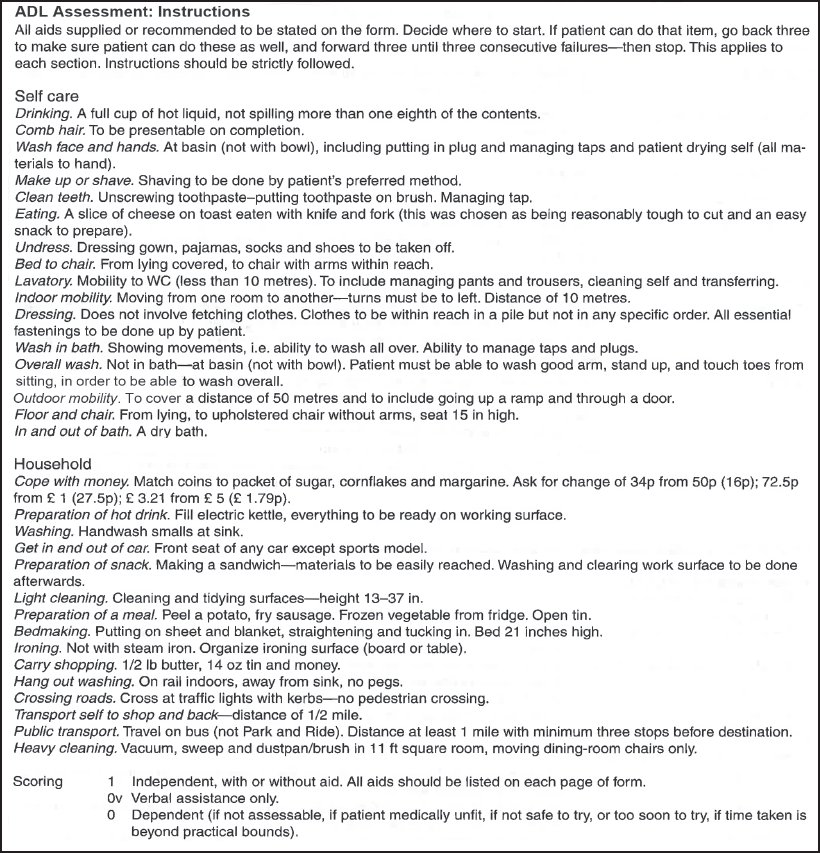

Two excellent functional assessment tools for older patients who have suffered a stroke are the Frenchay Activities Index and the Rivermead ADL Scale.40,41 The Rivermead was specifically designed for older patients. See Figure 12-5 for the Frenchay Activities Index and tool. See Figure 12-6 for the Rivermead ADL Scale explanation and tool.

Carr and Shepherd Evaluation

Carr and Shepherd,42 physical therapists from Australia, have a different way of analyzing patients who have sustained strokes. These therapists have developed an entire strategy based on motor relearning. Their strategy is to eliminate unnecessary movements and to better organize the movement patterns. It is important to understand this principle when looking at their evaluation strategies. For instance, when evaluating upper limb function, instead of grading the function in terms of synergies or range of motion deficits, this approach outlines common problems and compensatory strategies. For example, in the arm, common problems are (1) poor scapular movement and persistent depression of the shoulder girdle; (2) poor muscular control of the glenohumeral joint caused by a lack of abduction, flexion, and inability to sustain position; and (3) excessive and unnecessary elbow flexion, internal rotation, shoulder, and forearm supination.

In looking at the hand, this approach would consider the following dysfunctional movement patterns:

❖ Difficulty in grasping

❖ Difficulty in extending and flexing metacarpal phalangeal joints

❖ Difficulty with abduction and rotation of the thumb

❖ Difficulty cupping the hand

❖ Inability to hold different objects while moving the arm

❖ Tendency to pronate the forearm

❖ Excessive extension of the fingers and thumbs

❖ Inability to release objects

❖ Difficulty with abduction and rotation with the thumb in order to grasp

Figure 12-5A. The Frenchay Activities Index.

During assessment, the therapist would look at these deficits, identify them, and treat them.

Carr and Shepherd’s method42 of assessing lower extremity and trunk deficits is to describe them in terms of functional tasks, such as walking, balance, standing, standing from sitting, and sitting over the edge of the bed. In an analysis of sitting over the side of the bed, Carr and Shepherd identified 2 common problems: (1) flexion of the hip and knee on the affected side and (2) flexion of the shoulder and protraction of the shoulder girdle, which results in the patient’s inability to use the appropriate body mechanics to get out of bed.

This analysis can then be easily transferred to the appropriate treatment strategies for working with these patients. More specific evaluative and treatment information is available in Carr and Shepherd’s book titled A Motor Re-Learning Programme for Stroke.42 In a subsequent section of this chapter, a specific form developed by Carr and Shepherd is examined that goes over some of these points.42

In evaluating strength deficits, several studies have made a comparison between extension and torque in the knees as well as various other joints of the body, and it can be a reliable and valid measure in patients with stroke.43,44 Muscle fatigue in the unaffected knee and ankle impairs postural control and debilitates kinematic movement of ipsilateral and contralateral lower limbs, and it may place fatigued patients with stroke at greater risk for falls.45 Therefore, therapists can use manual muscle tests or dynamometry readings to assess strength in their older patients with a stroke.43–45

Olney and Colborne’s Gait Assessment

Another consideration that is extremely important in the area of stroke is the analysis of gait. In a particularly valuable journal article, Olney and Colborne describe some of the deficits in gait and discuss methods of treating the gait problem. They also divide the gait pattern into phases. The first phase, “late swing to foot flat,” identifies 3 problems for patients who have sustained a stroke: (1) inability to attain full hip flexion during swing, (2) inability to extend the knee fully, and (3) inability to activate ankle dorsiflexor muscles. In addition, patients with stroke may hyperextend the knee to avoid the problem of instability.

The next phase of gait that presents problems is foot flat to heel off. Problems noted here are the decreased use of hip extensor muscles, limited hip extension motion, and that ankle plantar flexors contract inappropriately.

Figure 12-5B. The Frenchay Activities Index. (Reprinted with permission from Holbrook M, Skilbeck CE. An activities index for use with stroke patients. Age Ageing. 1983;12[2]166-170.)

The next phase—push off, pull off in early swing—causes residual weakness of ankle plantar flexors and hip flexors. It also results in the stance phase of the affected side being longer than normal, and the body’s weight being transferred to the lower limb through push off.46

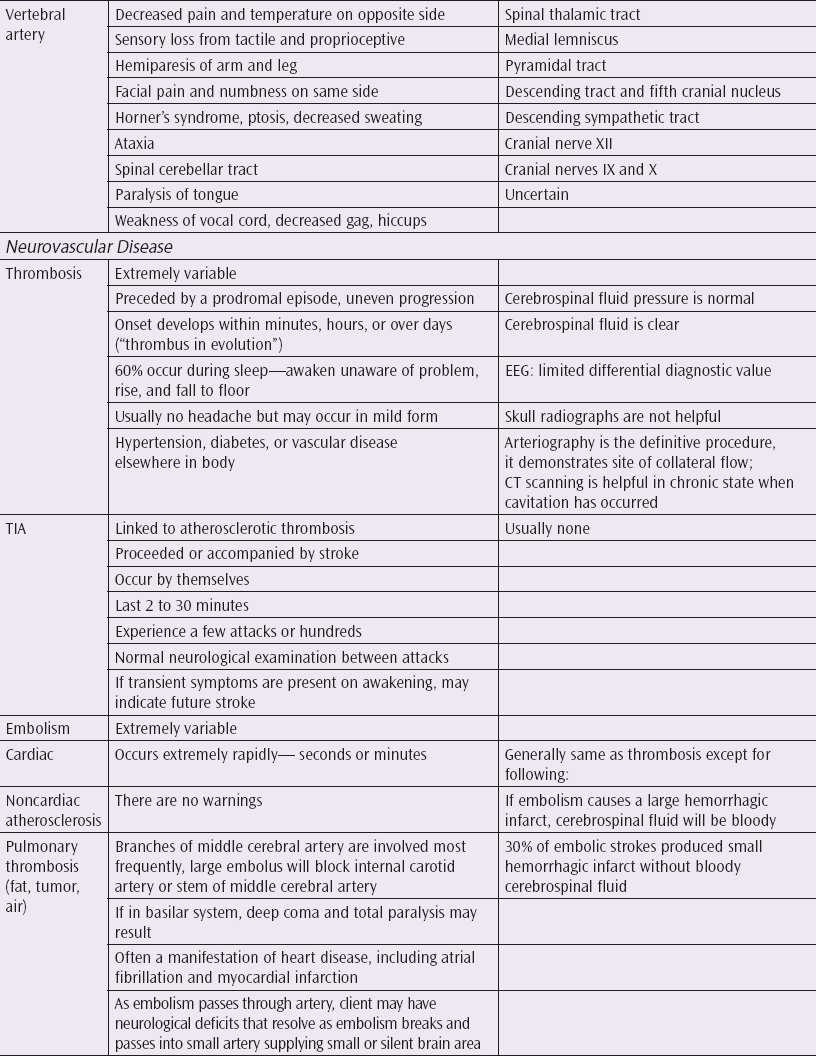

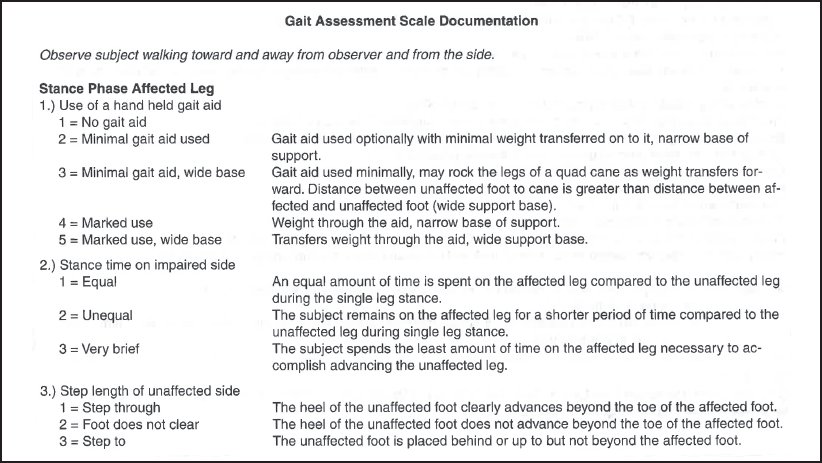

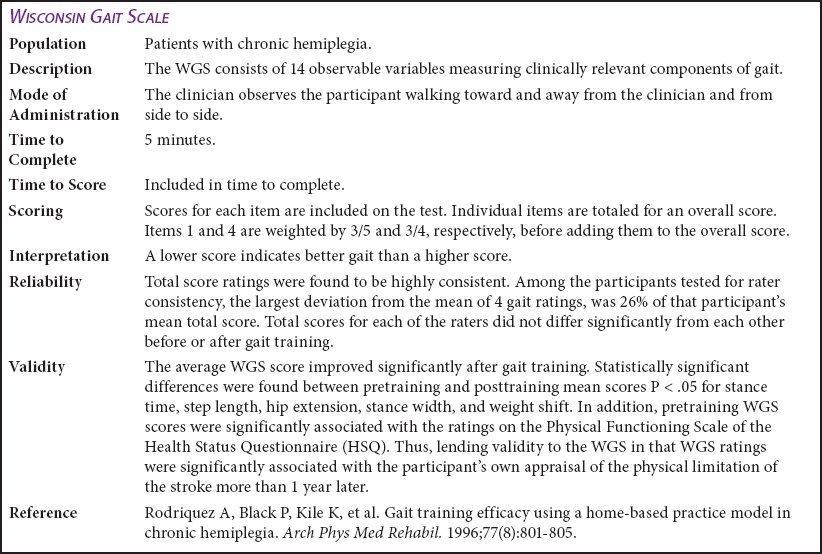

An excellent clinical tool for assessing gait in older patients with stroke is the Wisconsin Gait Scale. See Figure 12-7 for the explanation, instructions, and tool.47

Pusher Syndrome Assessment

Common findings of sensory deficits on the hemiside of a patient with Pusher syndrome are hemianopsia, problems with proprioception, and somatosensory deficits that contribute to postural inattention and difficulties with postural adjustments.48 Perceptual dysfunction includes unilateral neglect and agnosia. Cognitive function is usually decreased with significant memory impairments, impulsivity with decreased attention (typical of left hemiplegia), lack of insight or understanding of problems, and apraxia.

Motor function in Pusher syndrome includes overuse of extension on the sound side with ipsilateral pushing and predominance of a flexion synergy pattern in the affected lower extremity.31,32,48 Posturally, the head and trunk are held toward the hemiside with increased weightbearing on the involved side and shifting of the trunk away from the sound side. The patient’s balance is severely disturbed with an inability to find a midline orientation. In fact, the patient resists all attempts to assist in centering of the center of motion within the base of support. The patient pushes back strongly when weight transfer is attempted.

Typically, the individual shows no concern or fear of falling and does not automatically compensate for loss of balance with adjustments to support body weight. During the stance phase of gait, the patient demonstrates inadequate extension of the involved leg. During stepping, the patient is unable to transfer the weight efficiently onto the sound limb, and the hemi-leg typically adducts strongly during swing (scissors).31–33,48 Functional assessment reveals profound difficulties with sit to stand and transfers. The patient is often unable to stand without assistance.

Figure 12-6A. Rivermead ADL Scale.

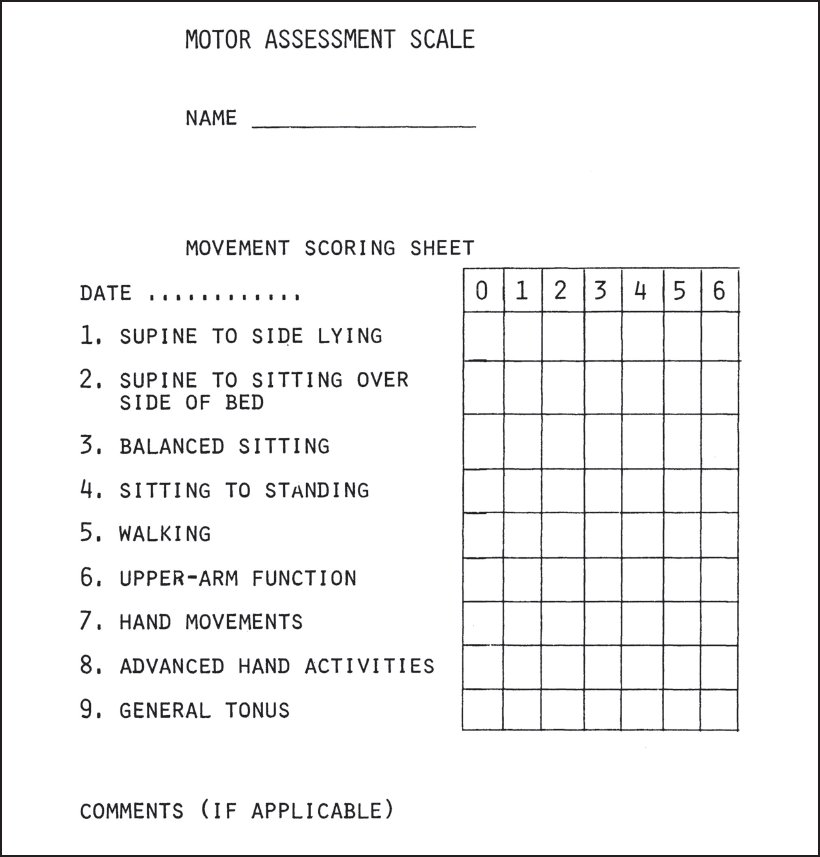

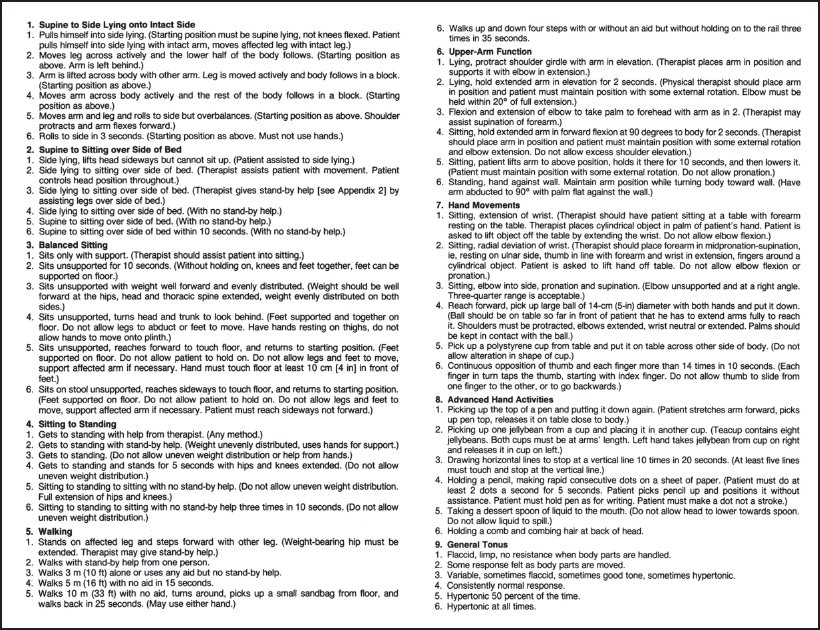

Motor Assessment Scale

Specific compacted tests for the assessment of patients who have sustained a stroke are somewhat difficult to find, but they do exist. Carr and Shepherd have developed the Motor Assessment Scale shown in Figure 12-8A. All items on the form are constructed so that a score of 6 indicates optimal motor behavior. The criteria for scoring are listed in Figure 12-8B. These particular criteria are self-explanatory and give the examiner a 6-point scale from which to assess the patient and show improvement in a very simple form.49

When evaluating a patient with stroke, it is important to choose the tools that will appropriately reflect the patient’s status and the methods to be used in the evaluation treatment progression. Several different types of tools have been provided and are considered next.

Treatment Interventions

There are a number of treatment techniques commonly used by physical therapists ranging from the classic therapeutic exercise to the proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation to the Bobath and Brunnstrom techniques. A brief discussion of Carr and Shepherd’s work follows in the next section. Treatment considerations for gait are also discussed, as is research on various types of ancillary modalities that can be used for the treatment of stroke deficits.

Carr and Shepherd’s Approach

Their treatment revolves around the following 5 principles49:

- Unnecessary muscle activity is eliminated.

- Any human activity becomes better organized and more effective when it is practiced.

- A muscle response depends on the condition of the muscle at the moment with the following perimeters: length, velocity, temperature, and joint ankle.

- The body must have the ability to adjust to gravity and change segmental alignment for all motor activities. Therefore, the person must be trained to preserve balance.

- A learned task is not just doing the task in front of a therapist. A learned task is when a person can do it in a situation without actually thinking.

In their treatment approach, Carr and Shepherd go through 4 steps: (1) analyze the task, (2) practice the missing component, (3) practice the task as a whole, and (4) transference of training.

Figure 12-6B. Rivermead ADL Scale. (Reprinted with permission from Lincoln NB, Edmans JA. A revalidation of the Rivermead ADL Scale for elderly patients with stroke. Age Ageing. 1990;19:19-24.)

An example of this would be a patient who has difficulty standing. First, analyze the difficulty (eg, hip position). Second, practice the missing component. For instance, the difficulty in standing comes from the patient’s hip position (ie, work with the hip). Third, practice this task (ie, standing with proper hip position). Fourth, transfer to another activity with the same problem (ie, standing in the proper position with a slight bend on a stool or a wedge under the foot).49

During treatment, motor tasks are practiced in their entirety. There is no “technique”; the person is just instructed and manually guided through various deficits. The patient may first be passively placed in the proper position, and then the patient takes over active control. As the patient develops more control, the therapist does less.

The most important component of Carr and Shepherd’s approach is the patient’s contribution to the effort. Patients are encouraged to do the exercises as often as possible and to keep a notebook of their efforts and responses. In the notebook, the patients are encouraged to write down their actual program progression.49

Figure 12-7A. Wisconsin Gait Scale.

Figure 12-8A. Motor Assessment Scale. (Reprinted with permission from Carr J, Shepherd R, Nordholm L, Lynne D. Investigation of a new motor assessment scale for stroke patients. Phys Ther. 1985;65[2]:175-180.)

Figure 12-8B. Criteria for scoring. (Reprinted with permission from Carr J, Shepherd R, Nordholm L, Lynne D. Investigation of a new motor assessment scale for stroke patients. Phys Ther. 1985;65[2]:175-180.)

Shoulder Problems in Hemiplegia

Shoulder pain in hemiplegia has always been a concern, and several clinicians have suggested that excessive distraction on the shoulder may lead to pain.29,40,50 The use of overhead pulleys is described as the highest risk of developing shoulder pain for patients with hemiplegia, and it was suggested that this should be strongly discouraged with these patients.50 Stabilizing the shoulder is the key for maintaining position and regaining function. In training upper extremity problems, it is preferred to provide increased weight training through the upper extremity as well as facilitating proper positioning.40,49–51

It is not necessarily the position that explained the “synergistic” increased force of the elbow strength but possibly the length of the muscle in various positions. Therefore, in working with the upper extremity, it is important to look not only at the neurologic factors, such as tone, but also at the length-to-t ension relationship of the muscles. Therapists should facilitate range of motion and proper posture as well as encourage weightbearing through the upper extremity in the proper position.51

Gait Treatment Suggestions

The upright control evaluation mentioned earlier differentiated different gait variations. In addition, in the same study from Rancho Los Amigos, the authors outlined a specific program for lower extremity problems.47 Their treatment techniques revolve around the use of ankle-foot orthotics with various types of dorsiflexion stops and electrical stimulation to the weak areas. For example, if a therapist notices stance deviation of inadequate hip and knee extension, he or she can suggest ankle-foot orthotics with dorsiflexion stops and electrical stimulation to the quadriceps or gluteus maximus for strengthening and facilitation. Inhibitive casting is used for excessive plantar flexion or with increased tone. Prolonged icing is suggested to inhibit tone. The treatment approach is to divide the various phases of gait and treat each separately according to deficit. Motor control is frequently organized on a task-oriented basis using a common set of rehabilitation strategies to simultaneously achieve body support, balance control, and forward progression during gait. Hemiparesis following stroke is due to disruption of the descending neural pathways, usually with no direct lesion of the brainstem and cerebellar structures involved in motor automatic processes. After stroke, improvements of motor activities including standing and locomotion are variable but are typically characterized by a common postural behavior that involves the unaffected side more for body support and balance control, likely in response to the initial muscle weakness of the affected side. Various rehab ilitation strategies are regularly used or are in development targeting muscle activity and postural and gait tasks, using more or less high-technology equipment. Reduced walking speed often improves with time and with various rehabilitation strategies, but asymmetric postural behavior during standing and walking is often reinforced, maintained, or only transitorily decreased. This asymmetric compensatory postural behavior appears to be robust, driven by support and balance tasks maintaining the predominant use of the unaffected side over the initially impaired affected side. Based on these elements, stroke rehabilitation including affected muscle strengthening and often stretching would first need to correct the postural asymmetric pattern by exploiting postural automatic processes in various particular motor tasks secondarily beneficial to gait.52 Clinicians should always keep in mind that the observed gait pattern might be associated with many variables including the time since stroke, the affected cerebral hemisphere, and lesion etiology.52

Treatment of gait disturbances in the patient with Pusher syndrome requires intact cognition and active patient participation. The focus needs to be on early resumption of upright postures (sitting and standing), transitional movements (supine to sit and sit to stand), and a concentration on active movements (guided or assisted). The goal is basically to “recalibrate” the patient’s perception of upright posture by providing him or her with feedback about movement outcomes and positional correctness. Maximizing tactile and proprioceptive inputs facilitates correct muscle contraction. Emphasizing stability during early standing with biofeedback for regaining a symmetric and stable midline position can be accomplished through physical and verbal cues.52–55

In the area of gait, it appears that weight shifting is one of the biggest problems. Patients must be taught the concept of proper weight shifting, which can be done using bicycle ergometry or electrocardiography for proper muscle use.52,54,56,57

Despite the various techniques suggested for stroke intervention (ranging from therapeutic exercise to biofeedback), the therapist must be careful to check the efficacy of the various treatment programs. Recent studies52–57 showed that symmetry and weight shifting strongly correlated with motor function. These components appear to be very important and should be treated vigorously with weight-shifting exercises. In contrast, Trueblood and coworkers56 showed that pelvic positioning exercises were helpful while the patient did the exercise. However, after the exercise session, patients who have sustained a stroke did not carry the pelvic position into daily activities.56 These are important considerations in the development of comprehensive therapeutic strategies.

Finally, both contemporary facilitation and neuroplasticity-oriented approaches and traditional exercise targeted at reflex and synergistic elements in stroke improved functional and motor performances, and there was no difference between the 2 exercises.58 This study provides food for thought, especially for those working with the geriatric patient. Finding the most appropriate program, working within the patient’s tolerance, and reviewing the results that accompany the treatment progression are extremely important for achieving the optimal outcomes. See Appendix B for evidence-based treatment ideas.

ALZHEIMER DISEASE

AD, acknowledged as a progressive multifarious neurodegenerative disorder, is the leading cause of dementia in late adult life. Pathologically, it is characterized by intracellular neurofibrillary tangles and extracellular amyloidal protein deposits contributing to senile plaques. Over the past 2 decades, advances in the field of pathogenesis have inspired researchers to investigate novel pharmacologic therapeutics centered more toward the pathophysiological events of the disease. The currently available treatments (ie, acetylcholinesterase inhibitors rivastigmine, galantamine, and donepezil and N-methyl D-aspartate receptor antagonist memantine) contribute minimal impact on the disease and target late aspects of the disease. These drugs decelerate the progression of the disease and provide symptomatic relief but fail to achieve a definite cure. While the neuropathological features of AD are recognized, the intricacies of the mechanism have not been clearly defined.59 Physical therapy is an important adjunct to current medical interventions to assist in maintaining the highest functional capabilities of the patient. As a progressive disease, physical therapy interventions will change as the disease progresses.

A concise discussion of the incidence and etiology of AD is provided in Chapter 5. This discussion focuses on evaluation, staging, and intervention in patients with AD. The challenge for the geriatric rehabilitation therapist working with patients with AD is to apply creative solutions to the problem of finding activities that maintain physical health. Keeping these individuals active enough to generate fitness benefits should be the primary goal of intervention in this population. Avoiding restraints is crucial. Although this patient population may appear physically healthy, they are susceptible to falls and other accidents resulting in orthopedic and other types of injuries. The clinical features of patients with AD are a gradual but relentless onset of symptoms including impairment of recent memory, disorientation, confabulations, and retrogressive loss of remote memories.59 Over time, reasoning ability, concentration, speech, and handwriting degenerate. In the early phases of the disease, motor function is well maintained; however, as the disease progresses, neurologic involvement often renders the patient with AD bedridden. In late stages, patients can deteriorate to a nonfunctional, vegetative state.

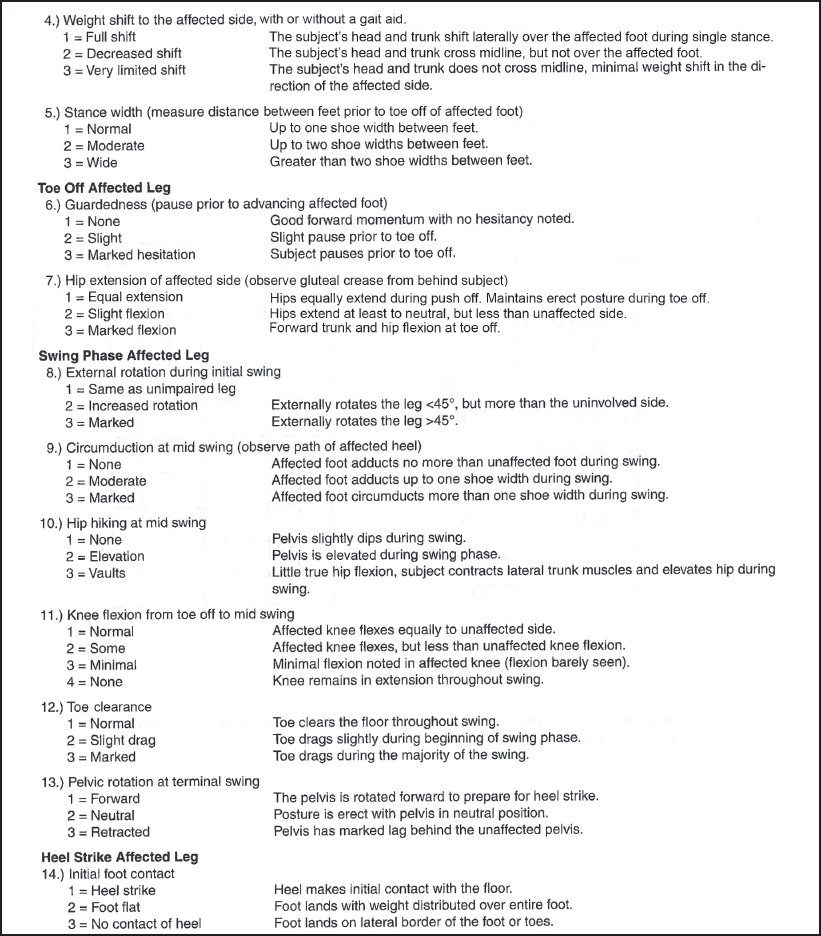

Table 12-7. Stages of Alzheimer Disease

STAGES | SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS |

| Early stage (I) | Forgetfulness Mild memory deficit Difficulty with novel or complex tasks Apathy and social withdrawal |

| Middle stage (II) | Moderate to severe objective memory deficit Disorientation to time and place Language disturbance Visuoconstructive difficulty Apraxia Personality and behavioral changes Requires supervision |

| Late stage (III) | Intellectual functions virtually untestable Verbal communication severely limited Incapable of self-care Incontinence of bladder and bowel |

| Terminal stage (IV) | Unaware of environment Mute Bedridden Joint contractures Pathological reflexes Myoclonus |

| Associated coexisting neurologic disorders | Increased tone Seizures Movement disorders Gait disorders |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree