Primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL) is a rare aggressive high-grade type of extranodal lymphoma. PCNSL can have a variable imaging appearance and can mimic other brain disorders such as encephalitis, demyelination, and stroke. In addition to PCNSL, the CNS can be secondarily involved by systemic lymphoma. Computed tomography and conventional MRI are the initial imaging modalities to evaluate these lesions. Recently, however, advanced MRI techniques are more often used in an effort to narrow the differential diagnosis and potentially inform diagnostic and therapeutic decisions.

Key points

- •

Most cases of primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL) are of the B-cell type (90% are diffuse large B-cell lymphoma) and a small subset are of T-cell lineage.

- •

PCNSLs are highly cellular lesions with tightly compacted cells, which translate into high density on computed tomography scan, low signal on T2-weighted imaging, and restricted diffusion on diffusion-weighted imaging.

- •

A variety of intracranial pathologic conditions can mimic PCNSL, such as high-grade gliomas, toxoplasmosis, subacute infarction, and tumefactive demyelinating lesions.

Introduction

Primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL) is a rare aggressive high-grade type of extranodal lymphoma. In PCNSL, the lymphoma is restricted to brain parenchyma, meninges, spinal cord, or eyes, without evidence of disease outside the central nervous system (CNS) at the time of initial diagnosis. Most cases of PCNSL are of the B-cell type (90% are diffuse large B-cell lymphoma), and a small subset are of T-cell lineage. PCNSL is more frequently seen in immunocompromised patients but it can occur in the immunocompetent population. The incidence of PCNSL has shown a growing trend from 3.3% before 1978 to 6.6% to 15.4% of all primary brain tumors in the early 1990s, due to increased prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and use of immunosuppressive drugs for transplantation. However, subsequently, the incidence of PCNSL declined secondary to the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART).

The mean age of diagnosis for PCNSL is 60 years old and it is more common in women. Patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) are generally diagnosed at a younger age than those without this disease. A smaller peak is also observed in the first decade of life due to pediatric AIDS.

Clinically, PCNSL may mimic other intracranial pathologies on imaging such as encephalitis, demyelination, and stroke. Personality changes, cerebellar signs, headache, seizure, and motor dysfunction may occur. Constitutional symptoms may also be present but they are more common in T-cell lymphoma. Early diagnosis and treatment can sometimes reduce the irreversible deficits of this disease.

In addition to primary lymphoma, the CNS can be secondarily involved by systemic lymphoma in 10% to 15% of patients, with a tendency to occur early at a median lag of 5 to 12 months after the primary diagnosis of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL). The systemic lymphoma is almost always aggressive NHL and patients with systemic Hodgkin disease are at very low risk of CNS involvement.

Introduction

Primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL) is a rare aggressive high-grade type of extranodal lymphoma. In PCNSL, the lymphoma is restricted to brain parenchyma, meninges, spinal cord, or eyes, without evidence of disease outside the central nervous system (CNS) at the time of initial diagnosis. Most cases of PCNSL are of the B-cell type (90% are diffuse large B-cell lymphoma), and a small subset are of T-cell lineage. PCNSL is more frequently seen in immunocompromised patients but it can occur in the immunocompetent population. The incidence of PCNSL has shown a growing trend from 3.3% before 1978 to 6.6% to 15.4% of all primary brain tumors in the early 1990s, due to increased prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and use of immunosuppressive drugs for transplantation. However, subsequently, the incidence of PCNSL declined secondary to the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART).

The mean age of diagnosis for PCNSL is 60 years old and it is more common in women. Patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) are generally diagnosed at a younger age than those without this disease. A smaller peak is also observed in the first decade of life due to pediatric AIDS.

Clinically, PCNSL may mimic other intracranial pathologies on imaging such as encephalitis, demyelination, and stroke. Personality changes, cerebellar signs, headache, seizure, and motor dysfunction may occur. Constitutional symptoms may also be present but they are more common in T-cell lymphoma. Early diagnosis and treatment can sometimes reduce the irreversible deficits of this disease.

In addition to primary lymphoma, the CNS can be secondarily involved by systemic lymphoma in 10% to 15% of patients, with a tendency to occur early at a median lag of 5 to 12 months after the primary diagnosis of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL). The systemic lymphoma is almost always aggressive NHL and patients with systemic Hodgkin disease are at very low risk of CNS involvement.

Imaging findings

Secondary Central Nervous System Lymphoma

CNS involvement by systemic lymphoma presents as leptomeningeal disease in two-thirds and as parenchymal disease in one-third of patients. Approximately half of the patients with secondary CNS lymphoma have progressive systemic lymphoma. Most of the remaining patients with apparently isolated CNS involvement will develop systemic disease within months. In addition, systemic lymphoma of the face (nasal cavity and paranasal sinus) can spread to the orbit and CNS via extraocular muscle involvement and direct perineural spread of neoplasm.

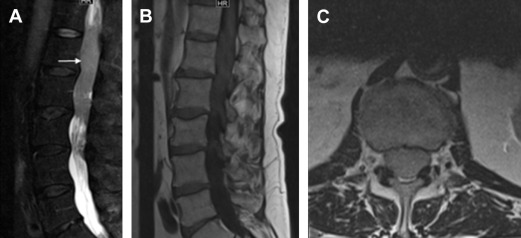

Contrast-enhanced MRI is the imaging modality of choice and can detect enhancement along the pial surface of the brain and spinal cord, subependymal ventricular system, and cranial or spinal nerve roots. It is more sensitive compared with contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT). Leptomeningeal disease can also invade the brain parenchyma and cause superficial cerebral lesions. Communicating hydrocephalus is frequently observed in patients with leptomeningeal disease.

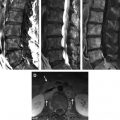

Parenchymal CNS involvement in systemic lymphoma can present as single or multiple parenchymal masses ( Figs. 1 and 2 ) and may accompany leptomeningeal disease. In a study of 18 subjects with parenchymal lymphoma, Senocak and colleagues demonstrated that homogenous nodular enhancement and supratentorial white matter involvement were present in all subjects with secondary lymphoma, with a butterfly pattern and infiltrative or perivenular enhancement in half of the subjects, with no significant distinctive radiologic characteristics between primary and secondary lymphoma of the brain parenchyma.

Primary Central Nervous System Lymphoma

General features

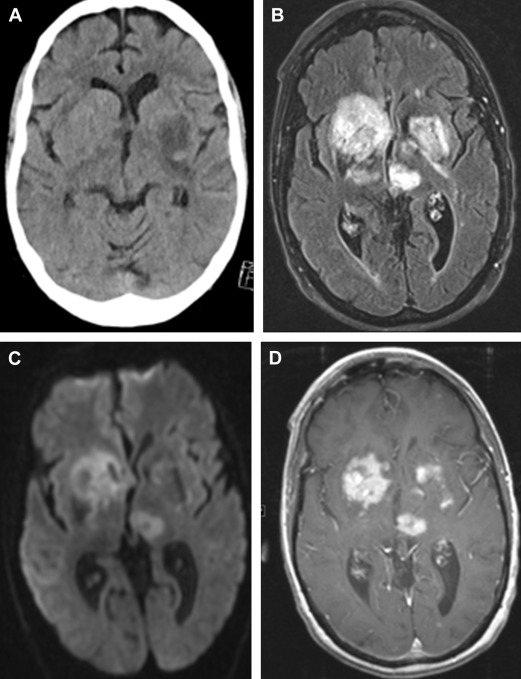

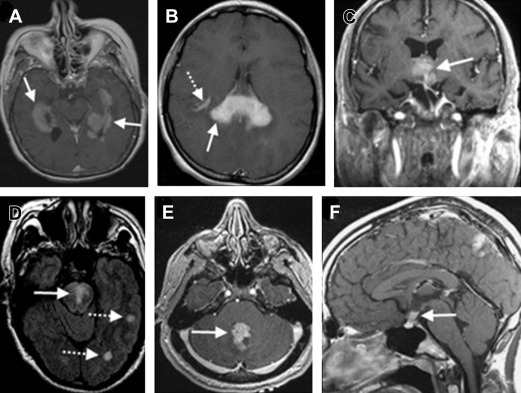

The most common presentation of PCNSL is a single intracranial mass. However, multiple masses are also quite common, and are seen in 20% to 40% of immunocompetent cases and 50% of the immunocompromised patients. The classic location of PCNSL is supratentorial in up to 70% of cases and has a predilection to involve the periventricular white matter. Basal ganglia are involved in 13% to 20% of patients. Involvement of the corpus callosum and extension to the other side of the brain can mimic the butterfly glioma appearance of glioblastoma multiforme (GBM). Superficial locations are also sometimes seen. Less commonly, lymphoma may involve other CNS structures ( Fig. 3 ) such as the hypothalamus, brainstem, cerebellum pituitary talk, and spinal cord.

Primary dural lymphoma is a rare subtype of PCNSL, which is usually a low-grade marginal zone lymphoma that primarily arises from the dura mater and may mimic meningioma and other dural based lesions. It can be single or multiple and, although it has a predilection for cerebral convexities, it may involve other dural structures. Primary leptomeningeal lymphoma, which has a better prognosis, is a rare subset of PSCNSL with estimated incidence of 7% of all PCNSLs. In a study of 48 subjects with primary leptomeningeal lymphoma, 62% had B-cell lymphoma, 19% T-cell, and 19% unclassified. These patients usually present with multifocal symptoms. Imaging demonstrates leptomeningeal enhancement and CSF analysis is the mainstay of diagnosis ( Fig. 4 ).

Ocular lymphoma can be a secondary extension of PCNSL and has been reported in up to 25% of patients or, very rarely, PCNSL is restricted to the eye. Ocular lymphoma can be diagnosed by slit lamp examination or cytologic examination of vitreal aspirate. On dedicated orbital imaging (with application of fat-saturation sequences), ocular lymphoma can be detected as a nodular enhancing mass. However, sensitivity is not high and a negative study does not exclude intraocular lymphoma.

Conventional imaging

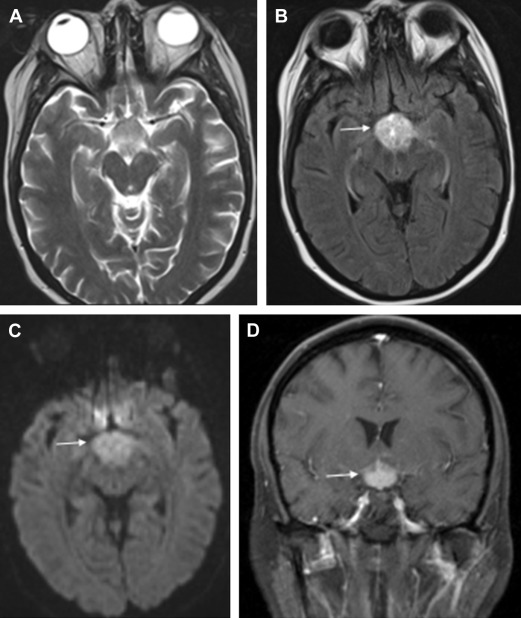

One of the histopathologic features of PCNSL is high cellularity with tightly compacted cells and high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio, which translates into some important imaging characteristics of PCNSL, such as high density on CT scan, low signal on T2-weighted imaging, and restricted diffusion on diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI). One of the important considerations in imaging of patients with PCNSL is the effect of steroids, which can cause apoptosis and necrosis in the mass, and can change the pattern of enhancement, metabolic activity, and also histopathologic findings.

On CT scanning, PCNSL usually present as a hyperdense mass ( Fig. 5 ) with contrast enhancement. This is an important diagnostic feature of PCNSL; however, less commonly it may also be isodense or hypodense, which may be misdiagnosed as infarction, demyelination, or encephalomalacia.

On MRI, PCNSLs are usually characterized by their periventricular locations, well-defined margin, moderate or marked edema, and intense and homogeneous nodular enhancement ( Fig. 6 ). On T2-weighted images, PCNSL shows short T2 relaxation times in most instances and thus appears isointense to hypointense in relation to gray matter, which is not common for most intracranial lesions. This feature is due to compact cells and a high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio. A long T2 relaxation time is uncommon for PCNSL and is correlated to the degree of necrosis. On the other hand, similar to many other lesions in the brain, PCNSL is hypointense to gray matter on T1-weighted imaging. Perilesional edema is usually present and is typically vasogenic in nature. However, cytotoxic edema has been reported in angiotropic large cell lymphoma (intravascular lymphomatosis) due to infiltration and cerebral infarction caused by vessel occlusion.

PCNSL typically enhances avidly and homogeneously in immunocompetent patients ( Table 1 ). Ring enhancement is seen in only 0% to 13% of immunocompetent cases. The pattern of enhancement is more variable in immunocompromised patients. Ring enhancement is the dominant pattern due to central necrosis and occurs in up to 75% of the patients. Homogeneous enhancement is less common in this group. Leptomeningeal enhancement has been reported in 16% to 41% of PCNSL at initial diagnosis. Rarely, PCNSL can present as T2 hyperintense lesions without contrast enhancement. Nonenhancing PCNSLs have been shown to be low-grade, less aggressive, lesions with a better prognosis in a few studies. Lymphomatosis cerebri is a rare entity characterized by diffuse supratentorial and infratentorial white matter T2 hyperintensity without contrast enhancement, which can mimic gliomatosis cerebri. Previously reported cases were in immune competent patients and the presenting symptoms can be nonspecific and include personality changes, cognitive deficit, and gait ataxia.

| Immunocompetent | Immunocompromised | |

|---|---|---|

| Location | White matter (central hemispheric or periventricular), superficial, corpus callosum | Gray matter (basal ganglion or other deep gray matter nuclei) |

| Number of lesions | Single, less likely multiple (20%–40%) | Single or multiple |

| Hemorrhage | Rare | Uncommon |

| Enhancement | Solid (ring in 0%–13%) | Ring (up to 75%) |

Calcification is rare at the time of presentation in PCNSL. However, it may develop after chemotherapy or radiotherapy. Similarly, hemorrhage is rare in PCNSL ( Fig. 7 ) and is associated with VEGF immunoreactivity.

Pattern of recurrence

Although the survival of patients with PCNSL has improved because as of multimodality treatment approaches, recurrence will eventually occur in most patients. One of the features of PCNSL relapse is that, unlike primary gliomas such as glioblastoma, recurrence usually does not occur at the site of initial tumor presentation ( Fig. 8 ). In a study of 16 immunocompetent subjects with PCNSL relapse, local recurrence at the site of the initial tumor presentation was found only in 25% of subjects, and subjects frequently presented with bilateral or contralateral recurrence.

Intravascular lymphomatosis

Intravascular lymphomatosis is a rare type of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma that is characterized by proliferation of the B-cells in the vascular lumen with no or minimal parenchymal involvement. It usually affects the CNS or skin, although any organ can be involved. If the CNS is involved, patients can present with a variety of symptoms, including focal sensory or motor deficits, generalized weakness, altered sensorium, rapidly progressive dementia, seizures, hemiparesis, dysarthria, ataxia, vertigo, and transient visual loss. It can mimic entities such as stroke, encephalomyelitis, Guillain-Barré syndrome, vasculitis, or demyelination. Diagnosis is often delayed and is based on findings on biopsy.

Imaging usually demonstrates multifocal areas of hypodensity on CT and increased signal on T2-weighted images without enhancement ( Fig. 9 ), although enhancement can be seen in a subset of cases and can have gyriform, speckled, ring-like, or homogeneous patterns. Due to intravascular nature of the disease, some patients can present with infarcts, which can be detected on diffusion weighted imaging.

T-cell lymphoma

T-cell lymphomas are rare in both adults and children, comprising only 2% to 8% of PCNSL cases. A review of 45 subjects with T-cell lymphoma revealed that the presentation and outcome seem similar to that of B-cell PCNSL. Compared with PCNSL of B-cell origin, there is less available literature with regard to imaging findings in subjects with T-cell PCNSL. Brain parenchymal involvement can be with solitary or multiple homogenously enhancing masses with a supratentorial predilection. Some studies also report a predilection for a subcortical location, relatively high incidence of cortical or intratumoral hemorrhage ( Fig. 10 ), and necrosis. They showed lower relative cerebral blood volume (rCBV) ratios compared with high-grade glioma, a finding shared by PCNSL of B-cell origin.

Adult T-cell lymphoma-leukemia (ATLL) is a T-cell neoplasm, associated with infection by the retrovirus human T-lymphotropic virus type 1. In patients with ATLL, secondary CNS involvement occurs in up to 25% of cases. The typical findings on imaging studies are multiple parenchymal lesions, with or without enhancement, involvement of the deep grey nuclei, and leptomeningeal disease.

Advanced Imaging

With conventional imaging techniques, a wide range of differentials are often considered for an intraparenchymal mass, covering typical and atypical imaging presentation of various brain diseases. Recently, advanced imaging techniques have been used in an effort to narrow the differential diagnosis and potentially change diagnostic and therapeutic decisions.

Diffusion-weighted imaging

DWI measures diffusion of water molecules in biological tissue. PCNSL commonly shows restricted diffusion due to high cellularity, appearing hyperintense on DWI trace images and hypointense on apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) maps ( Fig. 11 ). Although cellular portions of GBM and cellular metastases may also show reduced diffusion, mean ADC values are usually lower in lymphoma. ADC values are also higher in toxoplasmosis. However, the overlap between the 2 groups is significant and makes the discrimination difficult except in the extreme ranges of ADC values. In addition to added diagnostic value, ADC values have been shown to have prognostic value in patients with PCNSL. Barajas and colleagues demonstrated that low pretherapeutic ADC tumor measurements within contrast-enhancing regions were predictive of shorter progression-free survival and overall survival. In addition, they demonstrated that serial ADC measurements can act as a biomarker for treatment response because patients with significant change in ADC values had a prolonged progression-free survival. Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) is a more advanced version of diffusion imaging, requiring image acquisition in at least 6 directions, which enables better assessment of alteration in the white matter and subsequent generation of fractional anisotropy (FA) maps. Multiple DTI metrics, including FA, have been extensively studied in intracranial masses, including PCNSL. Multiple studies have shown that FA values are lower in PCNSL compared with GBM.