FIGURE 16.1 Frequency of various symptoms in patients with the carcinoid syndrome.

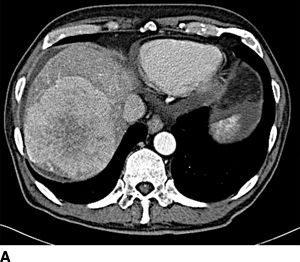

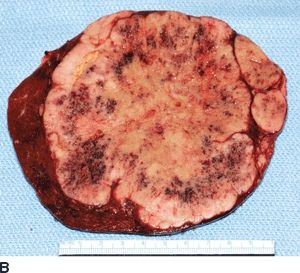

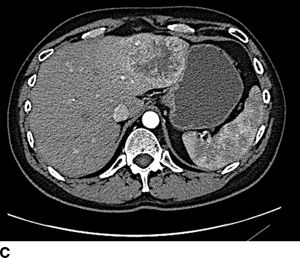

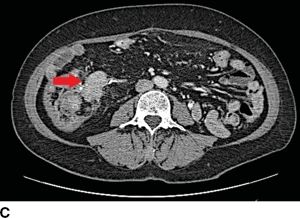

FIGURE 16.2 A. Contrast-enhanced CT with large right hepatic ileal carcinoid metastasis. The inferior vena cava is dilated, and the liver has a heterogenous appearance due to preexisting severe tricuspid valve regurgitation. B. Gross specimen of resected tumor—the patient underwent tricuspid/pulmonary valve replacement prior to liver resection. C. Contrast-enhanced CT with low-density jejunal carcinoid metastasis in left lateral sector. D. Gross specimen of resected liver tumor.

Diagnostic Evaluation

A comprehensive evaluation of patients with neuroendocrine liver metastases includes identification of the anatomic site of origin (whether in situ or previously resected), clinical and biochemical functional status, tumor histopathology and grade, and evaluation of extent and distribution of metastatic disease for resectability. Tumor site of origin is usually determined by endoscopy, contrast-enhanced enterography, radiolabeled scintigraphy, or cross-sectional imaging computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). NECs are termed functional if associated with a discrete clinical syndrome. The syndrome is confirmed biochemically through serum assays of respective neuroendocrine peptides. The clinical neuroendocrine syndrome is specific to the dominant functioning peptide. Not infrequently, multiple peptide levels are elevated but rarely do patients present with a combined clinical endocrinopathy. Nearly all NECs secrete chromogranin A; baseline concentration of this marker should be obtained regardless of clinical syndrome. Other secretory peptides should be evaluated as clinically indicated. Pathologic confirmation of NEC by fine needle aspiration or core biopsy (either metastases or primary tumor) is essential for clinical management. Grade of NEC is defined by proliferative activity via the Ki-67 index and mitotic rate. These key features of grading are critically important for clinical management. Indeed, pathologic findings correlate, in part, with the malignant behavior of NEC. In general, patients with well-differentiated grade 1 NEC benefit the most from aggressive therapy because of typically indolent growth. Patients with moderately differentiated grade 2 NEC have a less predictable and more aggressive course though are often still candidates for operative treatment. Operative intervention in patients with poorly differentiated grade 3 NEC is rarely indicated as these NECs are typically highly aggressive and are characterized by rapid dissemination and resistance to most therapeutic interventions. Currently, NEC is most frequently staged by the AJCC TNM staging system. Staging is crucial for planning overall management. As patients with hepatic metastases harbor by definition stage IV disease, the site and extent of local–regional disease and the site, extent, and distribution of other distant metastases to the peritoneum, lung, and bone significantly influence treatment planning.

Imaging

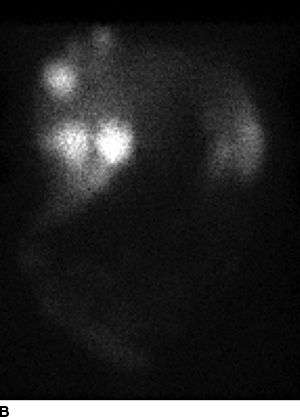

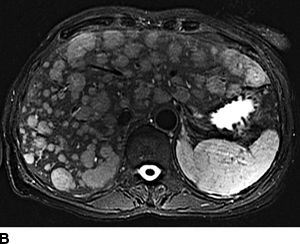

Radiolabeled somatostatin receptor scintigraphy (SRS) is the most sensitive and accurate imaging modality for diagnosis and initial staging particularly for identification of occult extrahepatic disease. Positive scintigraphy is dependent upon the presence of active somatostatin receptors (SR) on the NEC (Fig. 16.3). Current agents do not bind to all SRS receptors nor do all NEC harbor all SRs. In addition, SRS also predicts response to somatostatin analog therapy. More recently, fludeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (18-FDG-PET) also has been used as an alternative staging adjunct. However, contrast-enhanced CT remains the primary imaging study for assessing resectability of hepatic metastases from NEC. Metastases are hypervascular and are best visualized during the arterial phase of contrast administration. In patients with iodinated contrast allergies or significant steatosis, gadolinium-enhanced MRI is indicated; the contrast-enhanced T2-weighed sequences are most sensitive (Fig. 16.4). In our experience, MRI is complementary to CT with particular utility in detection of very small hepatic metastases that may alter treatment strategies. Liver-specific contrast agents such as gadoxetate disodium (Eovist) increase the sensitivity for detecting small NEC hepatic metastases. Such agents preferentially are taken up by hepatocytes; thus, small contrast-negative metastases not visible on CT are more readily identified. Additionally, contrast-enhanced cross-sectional imaging is essential to assess resectability of the primary NEC, if present, and to assess residual or recurrent regional disease if previously resected. Most patients with hepatic metastases from NEC harbor multifocal bilobar disease, though 25% of patients have isolated lobar disease.

FIGURE 16.3 A. Computed tomography revealing numerous enhancing metastases in the liver. B. In-111 octreotide scan revealing multiple large foci of intense radiotracer uptake in the liver as well as pancreatic tail, confirming metastatic (arrow) pancreatic NEC. C. Gross specimen of resected liver tumors.

FIGURE 16.4 Neuroendocrine liver metastases. A. Enhancing right lobe mass on the arterial phase of computed tomography. B. Diffuse bilobar metastases on T2-weighted MRI imaging.

In potentially resectable patients, radiologic data should estimate the future liver remnant volume in patients considered for extended or complex hepatectomy or in patients with bulky parenchymal disease. Formal upper and lower endoscopy and endoscopic ultrasound are also important tools with which to identify primary NECs. Patients with carcinoid syndrome should have a formal cardiac evaluation including echocardiography to evaluate the extent of right heart valvular disease. If present, valvular disease should be corrected prior to any major liver resection.

Potentially Curative Resection

Although NEC is considered indolent, metastatic disease can be associated with severe, life-threatening endocrinopathies or symptoms from locally invasive nonfunctional NEC. The leading cause of mortality aside from hormonal complications is extensive hepatic progression and hepatic failure. The timing and type of treatment should be considered in a multidisciplinary setting. Ideally, the first-line treatment for well-differentiated hepatic metastases from NEC without extrahepatic spread and unilobar alone or unilobar and limited contralobar metastases is resection with or without concomitant ablation. Potentially curative resection (R0) is defined as resection/ablation of all gross disease with an adequate functional liver remnant. Fewer than 50% of patients undergoing hepatic resection of metastatic NEC with hepatic metastases have R0 resection due to the extent of hepatic metastases. The historical 5-year survival for unresected patients with NEC liver metastases is approximately 30%. In contrast, the expected 5-year survival for patients after R0 resection of hepatic metastases based on retrospective series ranges from 60% to 80%. Factors correlating with long-term survival include size and site of metastases, tumor grade, extent of hepatic resection and baseline hepatic disease, presentation with stage IV disease, and impact of endocrinopathy such as carcinoid heart disease. Importantly, regardless of the apparent completeness of resection, disease progresses in most patients, either extra- or intrahepatically. Most patients will manifest disease progression within 5 years; the median identification of disease progression is 18 months. Perioperative octreotide is recommended to prevent the carcinoid crisis in patients with the carcinoid syndrome and other patients with demonstrable clinical control of endocrinopathies. Additionally, cholecystectomy is performed routinely during hepatic resection to avert cholelithiasis associated with somatostatin analog treatment and to potentially avoid ischemic cholecystitis or gallbladder necrosis associated with future arterial embolization and ablation, respectively. Adjuvant systemic chemotherapy is not established as the standard of care, but participation in clinical trials where available is recommended.

Palliative Resection

QOL related to endocrinopathies can be improved significantly through appropriate hepatic resection provided that residual disease is minimized. In general, durable relief of endocrine symptoms is obtained when nearly all radiographic metastases are resected even in the presence of gross residual disease. Palliative cytoreductive resection should be considered primarily in patients with endocrinopathies, particularly in patients who have failed medical management. Whether survival in patients without endocrinopathies is improved by palliative resection remains unproven. The completeness and duration of response to palliative resection are primarily based on residual metastatic volume and not resected metastatic volume. Given the growth kinetics of NEC, at least 90% or more of the hepatic metastases should be resected. In general, R2 resections are single-stage operations and are parenchymal sparing because disease progression is inevitable. Resection of the primary NEC may be undertaken concomitantly or at a staged procedure (Fig. 16.5). Palliative resection has limited applicability in patients with high-grade NEC or those with unresectable extrahepatic metastases. Importantly, no high-level evidence has shown that debulking improves survival or QOL compared to nonsurgical therapies. Palliative resection can be enhanced by subsequent percutaneous ablative therapies after hepatic regeneration. Notably, palliative resection does not preclude subsequent liver-directed therapies, antihormonal treatment, or chemotherapy.

FIGURE 16.5 Synchronous carcinoid metastasis. A. Computed tomography of large atypical carcinoid metastases replacing the left lateral sector. B. Gross intraoperative photo of this lesion. C. CT with infiltrative primary carcinoid arising in the terminal ileum and involving the small bowel mesentery (arrow). D. Gross intraoperative photo of this ileum tumor and the sclerotic adjacent mesentery.

Liver Transplantation

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree