Neoplasms Associated with Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome

We cannot deal with AIDS by making moral judgments or refusing to face unpleasant facts, and still less by stigmatizing those who are infected.

—Kofi Annan, former U.N. secretary general

HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS

HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS

One of the greatest public health challenges of the latter half of the 20th century has been emergence of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Although the biology of the virus has been elucidated, diagnostic tests have been created, and effective drugs and care systems have been established, HIV remains an epidemic in the 21st century, particularly in the developing world. HIV infection, immunosuppression, and enhanced tumor growth characterize the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).

Nearly 30 million people have died of AIDS in the past 30 years,1 and despite gains that have been made, AIDS remains a health catastrophe in those parts of the world with little or no access to life-sustaining drugs. In 2009, the most recent year for which worldwide statistics are available, over 33 million people were living with AIDS (including 2.5 million children under the age of 15 years), 2.6 million people became infected, and 1.8 million people died of AIDS. Nearly 70% of these events occurred in Sub-Saharan Africa.1 Although the toll of HIV infection in North America can be viewed as relatively small in comparison to other parts of the world, the statistics remain concerning. In 2009, 1.5 million persons in North America were living with HIV and there were 25,000 deaths attributable to AIDS.1 Many HIV-infected persons in the United States do not receive optimal care: for some, the monetary cost of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) is prohibitive, while for others, the toxicity associated with HAART is unbearable. Despite funded programs aimed at reducing the incidence of AIDS, 70,000 persons became infected with HIV in North America during 2009.1 Thus, even in such resource-rich areas as North America, AIDS is likely to remain a serious problem in the foreseeable future.

Human Immunodeficiency Virus and Malignancy

AIDS-associated malignancies are a well-recognized, not-infrequent, and potentially lethal consequence of the disease. Early in the epidemic, three types of malignancies showed a sufficiently increased incidence that they qualified as AIDS-defining conditions when they occurred in conjunction with HIV infection: Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS), non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), and carcinoma of the cervix. In 1981, the appearance of KS in young homosexual men heralded the association of tumors and HIV infection.2 Intermediate- or high-grade B-cell lymphomas in HIV-infected individuals were classified as AIDS-defining events in 1985.3 Cervical carcinoma was recognized in 1993 as an AIDS-defining illness for HIV-infected women.4 Data reported from the AIDS Cancer Match Registry Study (including more than 300,000 adult persons with HIV/AIDS) demonstrated the expected increased relative risks of developing the three AIDS-defining tumors,5 however, in addition, this study as well as others suggested an increase in some other tumors, such as Hodgkin lymphoma, anal carcinomas, skin cancers, and prostate cancer, as well as unusual pediatric age malignancies in HIV-infected children.6,7,8,9–10

By 1993, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) dropped the requirement of an AIDS-defining malignancy or other overt illnesses for a diagnosis of AIDS4; however, the burden of cancer in the HIV-infected population remains a substantial and potentially growing problem. The raw numbers from the HIV/AIDS Cancer Match Study and the CDC reflect the overall decrease in AIDS-defining neoplasms over the past decades: from 1991–1995 to 2001–2005, the estimated number of AIDS-defining cancers decreased from 34,587 to 10,325, whereas non-AIDS-defining cancers increased from 3,193 to 10,059,11 and this finding is corroborated by multiple other datasets.8,12 It is likely that this trend will continue as the HIV-infected population ages,13–14,15–17,18,19 and given that the AIDS population in the United States expanded fourfold from 1991 to 2005 primarily because of an increase in the number of people aged 40 years or older,11 cancer in the setting of HIV infection will continue to require our attention.

This chapter subsequently is organized by histologic type of HIV-associated malignancy. Epidemiology, patterns of disease, pathology, diagnostic evaluation, treatment, and prognosis are included. The use of radiation as it relates specifically to each malignancy in the setting of HIV is discussed. For additional details regarding the delivery of radiation, the chapters in this text addressing each specific neoplasm should be consulted.

It is of historical interest to note that in June 2001, the International Atomic Energy Agency issued a monograph, “The Role of Radiotherapy in the Management of Cancer Patients Infected by Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV),” which, given the paucity of data and the immense scope of the problem, attempted to provide some guidance for the treatment of HIV-associated malignancies.20 At the time, AIDS was an almost uniformly fatal disease, and it was against this background that the authors stated that for HIV-associated malignancies:

[T]he usual oncological rules of practice do not apply: cure at any cost is not a sensible option. Very often the best decision is simply to treat with the simplest, most effective, palliative regimen available. Any decision to treat radically has to be tempered by the realisation that the patient’s life span will be limited, regardless of the success or failure of the treatment for the malignant disease. Nowhere in oncology is an individualised approach to decision-making more important than in HIV oncology… for a patient with asymptomatic malignancy and HIV infection, active observation is a perfectly reasonable policy.20

Fortunately, a decade later, the outlook for HIV-infected persons is much improved, and the era of therapeutic nihilism has past. There is now solid rationale for including patients with HIV and cancer in clinical trials. The Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program has advised researchers that individuals known to be HIV positive should not be arbitrarily excluded from participation in clinical cancer treatment trials, and the National Cancer Institute has advocated that persons with HIV and cancer should only be excluded from cancer trials if there is a scientific reason for doing so.21 In general, for persons with HIV, the procedure is to attempt to utilize “standard” stage-directed treatments for each malignancy discussed. However, the authors do so with the major caveat that the “standard” treatment may need to be modified based on the immunologic status, the viral load, coexisting opportunistic infections, and comorbidities in any given individual.

Treatment-related toxicity will continue to be a concern as HIV infection yields to better therapies and the incidence of unrelated tumors increases. Laboratory data suggest that certain protease inhibitors may increase radiosensitivity; however, this has not been borne out in the clinic. See et al.22 compared the toxicity rates of radiation therapy in patients who were taking or not taking a second-generation protease inhibitor and observed no difference. Baeyens et al.23 demonstrated heightened sensitivity of HIV-infected T lymphocytes to damage from radiation, but the in vivo data are not uniformly supportive. Kaminuma et al.24 concluded that radiotherapy is safe, but HIV infection was associated with earlier onset (i.e., with lower dose) and more severe acute skin and mucosal toxicity. Mallik et al.,25 in a review of the literature, concluded that local control and disease-specific survival are not affected by HIV infection if the CD4 count exceeds 200 cells per cubic millimeter. This appears to be true even for tumors that are treated with relatively aggressive combinations of chemotherapy and radiation, such as carcinomas of the anal canal or of the head and neck region.26,27 Thus, in general, it appears that curative radiation therapy (with or without chemotherapy as the extent of disease dictates) provides disease control without imparting a degree of toxicity substantially beyond that traditionally seen in HIV-uninfected individuals. Nevertheless, the myelosuppressive nature of some of the agents incorporated into HAART regimens and the neurotoxicity of others raise concern when radiation therapy is being delivered to large volumes of bone marrow or over the central nervous system (CNS).28 If we are to continue to improve the outcome of HIV-infected persons with malignancies, close monitoring for toxicity, attention to immunologic parameters, and a strong emphasis on supportive care are essential when treating such patients with standard treatments.

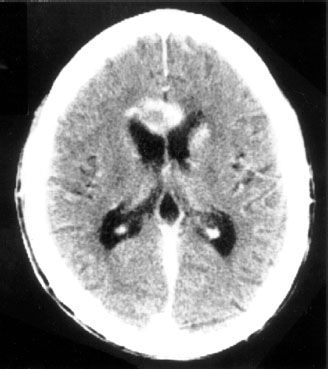

FIGURE 34.1. Example of periventricular location of human immunodeficiency virus–associated primary central nervous system lymphoma.

LYMPHOMA

LYMPHOMA

The incidence of lymphoma in association with HIV infection was reported as approximately 60 to 100 times greater than expected in the general population during the early years of the epidemic.29,30 Although primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL) was one of the initial CDC-approved criteria for a diagnosis of AIDS,31 the inclusion of systemic high-grade B-cell NHL did not occur until 1985.3 Its incidence was shown to correlate with the duration of immunosuppression, CD4 count 1 year prior to the diagnosis of NHL, and B-cell stimulation.32 Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) was implicated in its etiology by the finding of anti-EBV immunoglobulins and circulating EBV-infected B cells in the setting of HIV.33 Where available, HAART appears to have decreased the incidence of both PCNSL and NHL, most likely secondary to an overall decrease in the proportion of patients with low CD4 counts.12

Primary Central Nervous System Lymphoma

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

At its height, the incidence of NHL originating in the brain without evidence of systemic involvement in persons with AIDS was 3,600-fold higher than in the general population.34 HAART has decreased the high risk of developing this disorder in persons who are infected with HIV.35

Patterns of Disease

In most patients who have HIV-associated PCNSL, the diagnosis is suggested by the onset of headaches or a change in mental status.36,37 Unfortunately, PCNSL can be clinically and radiographically indistinguishable from other pathologic processes in HIV-infected patients. Neurocognitive dysfunction in HIV-infected patients is associated with a long differential diagnosis, including PCNSL, toxoplasmosis, herpetic infections, cryptococcus, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, neuroimmune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS), and HIV-associated dementia, leukoencephalopathy, and demyelination. In general, the typical radiographic findings of PCNSL are that of multiple contrast-enhancing lesions, often, but not exclusively, in a periventricular location (Fig. 34.1).

Diagnostic Workup

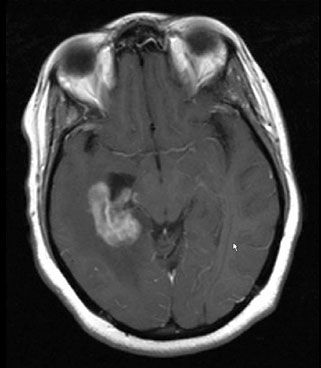

Prior to HAART, it was common for an HIV-infected patient to present with a clinical and radiographic picture that could be consistent with either toxoplasmosis or PCNSL (Fig. 34.2). A negative toxoplasmosis titer did not eliminate the diagnosis of toxoplasmosis, and similarly a positive toxoplasmosis titer did not preclude the presence of PCNSL.38,39 Because there was a high incidence of toxoplasmosis in the HIV-infected population, the standard first-line treatment for an HIV-infected patient who developed a neurologic abnormality and had a radiographically visible brain lesion consistent with either toxoplasmosis or CNS lymphoma was the institution of antitoxoplasmosis antibiotics. During the first decade of the epidemic, it was common to administer empiric cranial radiation therapy in patients who did not manifest clinical or radiographic improvement by the second or third week of antitoxoplasmosis treatment. However, as our knowledge of the myriad HIV-related opportunistic infections expanded and the poor outcome with this empiric approach was recognized, the emphasis shifted to recommending biopsy for definitive diagnosis.40

Pathology and Prognostic Factors

The majority of PCNSL are B-cell large immunoblastic types, and EBV DNA is identifiable in nearly all cases.41 Polymerase chain reaction amplification of EBV DNA in the cerebrospinal fluid is usually positive in these patients and may become negative following treatment.42 In general, PCNSL is seen later in the course of HIV infection than is systemic NHL. Patients usually have CD4 counts <50 cells per cubic millimeter before PCNSL becomes evident.43 Although the overall median survival of these patients is poor, patients no older than 35 years who have Karnofsky performance scores of at least 80% tended to survive 5 to 6 months, rather than the 2 months typically observed in less favorable subgroups.44

General Management

It has been suggested that the institution of HAART may result in regression of existing PCNSL, but to date scant evidence exists to support this claim.45–47 Methotrexate-based chemotherapy with or without whole-brain radiation therapy (RT) has been shown to prolong the median survival in immunocompetent patients who have PCNSL,48 and when possible, this approach should be considered for patients with HIV. However, many HIV-infected patients who are sufficiently immunosuppressed to develop PCNSL may be unable to tolerate methotrexate. In the pre-HAART era, chemotherapy was evaluated for HIV-associated PCNSL, with median survival on the order of 2 months.49,50 More recently, in the HAART era, a subgroup of HIV-positive patients who can tolerate aggressive therapy consisting of either methotrexate with or without whole-brain radiotherapy, may achieve longer survivals, although their outcome remains worse than the median survival of 41 months reported in immunocompetent patients treated with methotrexate-based chemotherapy.48,51

Radiation

Cranial irradiation alone in the treatment of PCNSL was essentially palliative, produced short-lived clinical and radiographic evidence of tumor response, and resulted in mean overall survival of 2 months.36,44,49,52–54,55,56–57,58 Recent intriguing data from Japan showed a survival rate of 64% at 3 years in a cohort of irradiated patients who were receiving HAART.59 Patients who received (or who were able to receive) doses 30 Gy or more fared better than those receiving lower doses. Unfortunately, one-third of persons who lived more than 12 months manifested leukoencephalopathy.

Although HAART appears to have decreased the incidence of HIV-associated PCNSL, it remains to be determined what the precise influence of aggressive antiretroviral treatment will be on the outcome of HIV-infected patients with PCNSL. However, it appears that survival is prolonged by HAART.60,61 There are anecdotal reports of regression of PCNSL with the institution of HAART and case reports of survival 2 years or more.45–47,62 Cohort data from Australia showed that in a subset analysis of 47 patients with biopsy-proven PCNSL, antiretroviral therapy with at least two agents along with RT was associated with better survival.63 In addition to immunomodulation by targeting HIV, attempts have been made to target EBV, which is nearly uniformly found in HIV PCNSL. Combinations of zidovudine, ganciclovir, and interleukin-2 were piloted by the AIDS Malignancy Consortium.64 The incidence of myelosuppression with this was high, and this remains an experimental approach.

FIGURE 34.2. Magnetic resonance image findings in a patient who presented with a change in mental status and was found to be human immunodeficiency virus positive. Differential diagnosis included primary central nervous system lymphoma; biopsy proved toxoplasmosis.

Systemic Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma

Epidemiology and Risk Factor

The incidence of NHL decreased with introduction of HAART, and this reflected the decreased number of HIV-infected persons with low CD4 counts.65 Although it appears that nonnucleoside transcriptase inhibitor–based HAART is as protective as protease inhibitor–based HAART and more protective than nucleoside analogs alone,66 cases of NHL among patients with multiclass antiretroviral resistance have been described as developing soon after newer-class antiretrovirals were initiated; this has raised the potential of IRIS-mediated NHL.67,68

Diagnosis

Rapidly developing adenopathy or constitutional B symptoms (fevers, unexplained weight loss, night sweats) are the most common presentations of HIV-associated systemic NHL. Nearly 75% of all patients will present with advanced-stage disease (stage III or IV), will manifest B symptomatology, and frequently have extranodal involvement.69 The most common histologic subtypes are high-grade B-cell lymphoma or Burkitt’s lymphoma; however, intermediate-grade (diffuse large cell type) lymphomas are not uncommon. As patients who have AIDS-NHL frequently have extranodal involvement, staging evaluation should include chest, abdomen, and pelvic computerized tomograms, bone marrow biopsy, and cerebrospinal fluid analysis.

Treatment

Treatment for AIDS-NHL lymphoma initially was based on high-dose chemotherapy regimens that proved to be toxic. Subsequently, therapy relied on attenuated doses of cytotoxic chemotherapy or standard-dose chemotherapy plus cytokine support; however, outcomes were still poor.70–74 Further study helped to define a regimen with high efficacy with acceptable toxicity using infusional cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and etoposide (CDE), and a multicenter trial employing this regimen showed that the median 1-year survival of 48% achieved with CDE was approximately twice as high as was achievable with previously standard regimens such as methotrexate with leucovorin rescue, bleomycin, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and dexamethasone.75 The advent of rituximab, an anti-CD20 antibody that has improved survival for patients with non-HIV-associated NHL, may improve the outcome in HIV-associated NHL. An AIDS Malignancies Consortium phase III trial that randomized patients to cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP) versus CHOP plus rituximab (R-CHOP) showed a higher complete response rate (57%) in the R-CHOP arm as compared with CHOP alone (47%); this, however, was not statistically significant and there was an increased risk of death from infection in the R-CHOP arm.76 A French trial also evaluated the safety and efficacy of R-CHOP for the treatment of AIDS-related NHL.77 This trial included 61 patients, two-thirds of whom achieved a complete response. The overall survival at 2 years was 75%, and although infections were seen, only one patient died from infection. The AIDS Malignancies Consortium (AMC034) trial randomized patients to EPOCH (etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, and doxorubicin) with concurrent rituximab versus EPOCH followed sequentially by rituximab.78,79 The patients who received concurrent rituximab achieved a complete response of 73%.

CNS prophylaxis with intrathecal chemotherapy has been controversial in the setting of high-grade NHL and HIV infection, but frequently was used, especially in patients with extranodal disease. However, it appears that patients who do not have EBV-infected tumors may not require such prophylaxis. The risk of CNS involvement was 10 times higher in patients who were EBV positive, as compared with those who were EBV negative.80 It may be that prophylaxis can be reserved for a selected subset of patients. The sustained-release formulation of intrathecal cytarabine may have an important role to play in both the prophylaxis and treatment of CNS meningeal involvement.81

A previously unrecognized form of lymphoma, called primary effusion or body cavity lymphoma, was identified in HIV-infected patients during the second decade of the epidemic.82 It appeared to be associated with human herpesvirus-8,83 and it accounted for approximately 4% of AIDS-related NHL.84 Typically, such patients present with an effusion in a body cavity, in the absence of widespread lymphadenopathy. The effusion contains numerous atypical lymphoid cells with a plasmacytoid appearance and an indeterminate (non-B or T cell) immunophenotype and clonal immunoglobulin heavy- and light-chain gene rearrangements. Multiple myeloma-1/interferon regulatory factor-4 protein expression can be used to differentiate primary effusion lymphoma from other lymphomas.85 Survival of patients who have primary effusion lymphoma remains very short, on the order of 2 to 5 months, even with aggressive therapy.

It is clear that with the availability of HAART, it became feasible to employ standard chemotherapy regimens, and a major question now is whether HAART should be administered in conjunction with, or after, chemotherapy. In general, it is recommended that zidovudine be avoided because of its myelosuppressive effects. The current thinking is that HIV-infected persons should be treated in the same aggressive fashion as noninfected persons, however, patients much be chosen carefully and monitored closely for toxicity.86,87

Radiation Therapy

The role of consolidative radiation therapy following systemic treatment in AIDS patients who have NHL has not been evaluated methodically. It had been suggested that radiation should be used as a consolidative boost in patients with bulky disease who have demonstrated slow or partial response to chemotherapy.88,89 More obviously, it also was indicated for palliation of bulky lesions and was used to provide palliative therapy for patients who develop lymphomatous meningitis. In lymphomatous meningitis, this approach was shown to result in a 60% to 70% clinical or cytological response, however, median time to progression was on the order of only 2 to 2.5 months.90,91

Results and Prognosis

Despite our best current therapies, patients who have AIDS-NHL generally have a poor overall survival. Early in the epidemic prognostic factors were identified that correlated with the length of survival.92–94 Patients who had bone marrow involvement, low Karnofsky performance status at diagnosis (<70%), low CD4 counts, or a prior diagnosis of AIDS had a median survival on the order of 4 months; those without these adverse features had a median survival of 11 months. Rossi et al.95 reported that the International Prognostic Index (IPI), a model designed to predict the outcome of NHL in general, is a reliable prognostic indicator of outcomes for patients who have AIDS-related NHL. Both the likelihood of complete response and median survival after treatment correlated appropriately with IPI score. Moreover, the IPI score correlated with the CD4 cell count, suggesting that the degree of immunodeficiency imparted by HIV infection influenced the aggressiveness of NHL. Ultimately, a prognostic model for systemic AIDS-related NHL treated in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy was established based solely on the IPI and the CD4 count.96

NHL remains an important cause of morbidity and mortality in AIDS patients. Registry data from San Diego suggest an improvement in median survival for these patients from approximately 4 months to 9 months after the introduction of HAART,35 however, data from Kaiser Permanente in California demonstrate that HIV-infected patients with NHL in the HAART era continue to endure substantially higher mortality compared with HIV-uninfected patients with NHL, with 59% of HIV-infected patients dying within 2 years after NHL diagnosis as compared with 30% of HIV-uninfected patients.97 There is hope that newer targeted agents, such as rituximab, which has shown an improvement in survival for patients with non-HIV-associated NHL, will improve the outcome in HIV-associated NHL. It is of interest that in developing countries challenged by the lack of HAART, efficacious regimens employing dose-modified oral chemotherapy have been developed, which result in outcomes comparable to the pre-HAART experience in the United States.98

Hodgkin Lymphoma

The relative risk of developing Hodgkin lymphoma in the setting of HIV infection (HIV-HL) is increased as compared with the general population as demonstrated by a joint Danish and U.S study of 302,824 HIV-infected patients that showed a relative risk of 11.5.99 Although data from the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study showed a stable incidence of this disease before and after the introduction of HAART,12 there is recent evidence that the incidence of this disease in the HIV-infected population increased after the introduction of HAART. Data from a large European cohort showed a rising standardized incidence ratio from 1983 through 2007, with multivariate analysis showing that HAART was associated with an increased risk of disease.18

The explanation for the rise in HIV-HL after combined antiretroviral therapy became widely available is unclear, however, one intriguing explanation involves the relationship between Reed-Sternberg cells and CD4 cells.100 The risk of Hodgkin lymphoma appears to peak when HAART reconstitutes the immune system and CD4 cells reach levels of 150 to 190 cells per cubic millimeter. It is postulated that Reed-Sternberg cells produce growth factors that increase the influx of CD4 cells, which in turn provide signals that cause the proliferation of Reed-Sternberg cells. If CD4 cells stimulate the growth of Reed-Sternberg cells, it would stand to reason that as HAART improves the CD4 cell count, more of these cells are available to stimulate growth of the cell associated with Hodgkin lymphoma.

Hodgkin lymphoma in HIV-infected individuals tends to be advanced, associated with B symptoms, and can present with unusual manifestations, such as presentation with a gastric or intracranial mass.101,102 In addition to the usual prognostic factors for Hodgkin lymphoma, low CD4 count and preexisting AIDS confer a worse prognosis.

In the past, only 50% of patients had a complete response following combination chemotherapy, and 2-year survival was on the order of 45%.103,104 How to integrate RT into the management of HIV-HL was also problematic. A report from M.D. Anderson Cancer Center suggested that radiation therapy was “appropriate” for approximately 50% of patients who had HIV-HL, usually in combination with chemotherapy; nevertheless, even in that series (with a median follow-up of 64 months), 5-year overall survival was only 54%.105

However, the outcome may be improving in the setting of HAART and combination chemotherapy.106 A phase II study in 59 patients with HIV-HL (52 of whom also received concurrent HAART) resulted in a complete response rate of 81% with the Stanford V regimen, although 3-year overall survival was only 51%.107 A more recent series from Germany reported a risk-adapted approach in 93 patients with HIV-HL.108 Patients with early-stage favorable Hodgkin lymphoma were treated with 2 cycles of adriamycin, bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine (ABVD) and 30 Gy involved field RT, those with unfavorable early-stage disease received 4 cycles of BEACOPP (bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, prednisone) and 30 Gy involved field, and those with advanced stage disease were treated with 6 to 8 cycles of BEACOPP. Importantly, BEACOPP was replaced with ABVD for patients with “far-advanced” HIV infection, and HAART was given concomitantly with chemotherapy. Early results are encouraging with a 1-year overall survival of 88%, although the outcome was worse for those patients with advanced stage disease. Additionally, of concern, even with careful attention to the risks of toxicity, four patients died of neutropenic sepsis.

In general, radiation therapy should be considered for HIV-HL for the same indications it is considered in non-HIV-associated Hodgkin lymphoma; however, there continues to be a paucity of data on its use and tolerance in this setting.

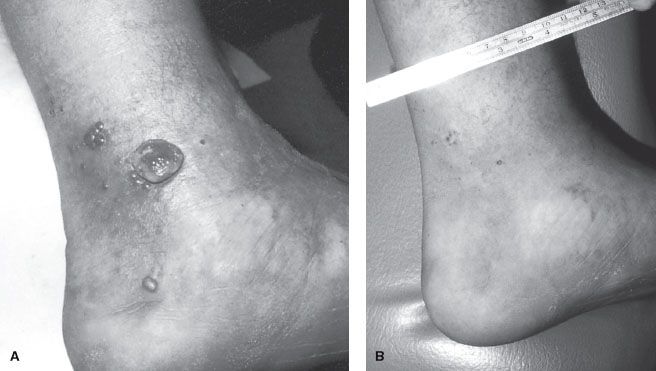

FIGURE 34.3. Purple, 1.5-cm nodular classic Kaposi’s sarcoma on the ankle of an elderly man. (From Krigel RL, Friedman-Kien AE. Kaposi’s sarcoma of AIDS: diagnosis and treatment. In: DeVita VT Jr, Hellman S, Rosenberg SA, eds. AIDS: etiology, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1988, with permission.)

KAPOSI’S SARCOMA

KAPOSI’S SARCOMA

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

At the start of the epidemic, AIDS often was identified by the diagnosis of KS, and KS in this setting became known as epidemic Kaposi’s sarcoma (EKS). People infected with HIV had at least a 20,000 times greater risk of developing KS than uninfected individuals.109 The discovery that HIV-infected gay or bisexual men were more likely than HIV-infected heterosexual men to develop KS was one of the first clues that KS or its etiologic agent might somehow be sexually transmitted.

With the introduction of progressively more effective antiretroviral therapies, the incidence of KS in the United States, as a component of AIDS, has diminished over time. A report from the International Collaboration on HIV and Cancer evaluating the cancer incidence from 23 prospective studies that included 47,936 HIV-seropositive individuals from North America, Europe, and Australia showed that the adjusted incidence rate for KS declined from 15.2 in the period of time from 1992 through 1996 to 4.9 between 1997 and 1999.110 A report from the Swiss HIV Cohort Study showed that the risk of developing KS declined by 66% during the 15 months after HAART was initiated (p = .001), as compared to the pre-HAART era.111

In December 1994, a herpes virus that appeared to be associated with the etiology of Kaposi’s sarcoma was identified.112 This was called human herpesvirus-8 (HHV-8) as well as KS-associated herpesvirus (KSHV). The virus was detected in both the epidemic (AIDS-related) and endemic (previously typical African) forms of KS, as well as classic (elderly men of Eastern European or Mediterranean ancestry) KS. In a 1996 report from the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study, antibodies to HHV-8 were detected in 80% of HIV-infected men who subsequently went on to develop KS.113 This suggested that KS resulted from infection with HHV-8, rather than being a direct result of HIV itself, or to cytokines induced by the HIV virus; HIV produced the immunosuppression that facilitated HHV-8 expression as KS. HHV-8 has a large number of genes that can encode homologues of host genes, many of which are involved in angiogenesis and the cell cycle. At present, six major subtypes (called A, B, C, D, E, and F) of HHV-8 are recognized based on the specific amino acid sequences of the gene K1 (ORF-K1) of the virus and further divided into subgroups known as clades (e.g., A1, A2, A3). Additionally, increased levels of interleukin-6, which is thought to be an important growth factor in HHV-8 associated neoplasms, have been found in tissues affected by HHV-8.114

Patterns of Disease

KS is characterized by purplish lesions on the skin or mucosal surfaces. The lesions can be macular, plaque-like, or nodular, with or without associated lymphadenopathy or lymphedema (Figs. 34.3–34.5). At presentation, skin lesions can be either single or multiple and may cause pain, bleeding, or disfigurement. As involvement of lymph nodes and lymphatic spaces occurs, progressive edema can result. This is seen most commonly in lesions involving the lower extremity, the inguinal regions, the genitalia, and the face. Visceral KS typically involves the aerodigestive tracts. Oropharyngeal lesions can result in life-threatening airway obstruction. Pulmonary involvement can result in life-threatening respiratory failure.

Diagnostic Workup

In addition to inspection of all visible skin and mucosal surfaces, the likelihood of visceral KS is sufficiently high that endoscopic evaluation of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract is appropriate for any patient with GI symptoms. In any patient who develops KS as the first sign of AIDS, a more comprehensive workup for HIV should be undertaken: complete physical examination, blood count and chemistries including CD4 lymphocyte count and viral load, chest x-ray, tuberculin test, anergy screen, and screen for sexually transmitted diseases.

Pathology

It is generally agreed that KS is a neoplasm of mesenchymal origin, and the histologic diagnosis of KS requires the identification of both spindle cell and vascular elements within the lesion. The spindle-shaped cells look much like fibroblasts and are generally considered the neoplastic element. Overall, the appearance often is suggestive of slitlike embryonic vascular channels filled with red blood cells; however, red cells characteristically are also found mixed within the spindle cell framework of the tumor.

FIGURE 34.4. A: Epidemic Kaposi’s sarcoma of the foot before treatment. B: Same patient approximately 1.5 years after 30 Gy was delivered in 10 fractions over 2 weeks by 6-MeV electron beam therapy (with bolus).