Chapter 77 Mycosis Fungoides

Mycosis fungoides (MF) is a low-grade, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma caused by skin-homing CD4+ T cells that form cutaneous patches, plaques, and tumors.1,2 MF was initially noted in 1806 when Alibert described a patient with cutaneous tumors that he attributed to yaws. Although the disease was initially termed pian fungoides, he later changed the name to mycosis fungoides.3 In 1938, Sézary and Bouvrain described a leukemic variant called Sézary syndrome (SS),4 and Lutzner and Jordan elucidated the ultrastructure of the Sézary cell in 1968.5 The term cutaneous T-cell lymphoma was introduced by Edelson in 1975 and encompasses a variety of cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorders, including MF/SS, adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma, primary cutaneous CD30+ anaplastic lymphoma, lymphomatoid papulosis, pagetoid reticulosis, and others.6 In clinical practice, the terms MF and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) are often used interchangeably; however, such usage is incorrect.7 MF constitutes only 50% of all CTCLs, and the clinical history and therapy for each subtype of CTCL are different.2

MF is a challenging disorder from all perspectives. Despite improving molecular techniques, diagnosis early in the course of disease is often difficult because of the nonspecific nature of skin lesions and the numerous benign dermatoses that may mimic MF. Once a diagnosis of MF has been correctly established, the optimal initial treatment strategy often remains unclear, given the heterogeneity of clinical presentations and limited data from controlled studies. Although radiotherapy is the most effective single agent in the treatment of MF,8 total skin electron beam therapy (TSEBT) is not readily available at many centers. This chapter provides a summary of the clinically relevant aspects of MF and describes the role and techniques of radiotherapy in patient management.

Etiology and Epidemiology

MF primarily affects adults over the age of 40 years, with incidence rates peaking in the seventh decade. The incidence of CTCL has consistently increased from 1974 through 2002, reaching a current yearly incidence rate of 9.6 cases per million.9 Risk factors for the development of CTCL include black race and male gender. Markers of high socioeconomic status, such as residence in areas with high home values, high level of educational attainment, and high physician density, are associated with an increased incidence CTCL; it is unclear whether these factors are causative or simply increase the likelihood of diagnosis.9

Etiologic agents for the development of MF remain highly speculative.10 Although numerous exposures to toxins, including pesticides, radiation, industrial solvents, tobacco, and alcohol, have been investigated, no consistent causative factors have been identified.11 High rates of seropositivity for both cytomegalovirus12 and human T-cell lymphotrophic virus type I13,14 have been reported, but these studies await further corroboration before a causal relationship can be inferred.15,16,17

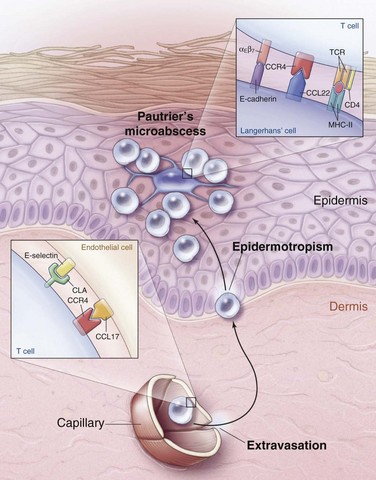

The observation that MF is more common in blacks and tends to present in sun-shielded areas (i.e., bathing suit distribution) suggests that sun exposure may protect against the development of MF. Sun exposure may mediate its protective effect by exerting a cytotoxic effect on either the malignant CD4+ T cell of MF or the epidermal antigen-presenting dendritic cell, also known as the Langerhans cell. This cell presents antigens to the malignant CD4+ T cells of MF and may stimulate their growth. The histologic evidence for this interaction is Pautrier’s microabscess, an intraepidermal collection of malignant CD4+ T cells clustered around an antigen-presenting dendritic cell. This finding is considered pathognomonic for MF and suggests that MF may be an antigen-driven malignant disease, though a specific antigen has yet to be identified.18

Prevention and Early Detection

No agents have been identified that will prevent the development of MF. Early diagnosis is critical, however, because local therapy directed against unilesional or oligolesional MF is highly curative.19–21 The most typical presentation of early disease—an erythematous patch with scale arising in a sun-shielded area—may be confused with a number of benign dermatoses, including atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, and tinea corporis.22 At this early stage, most of the lymphocytes noted on histopathologic studies represent reactive inflammatory cells rather than the malignant clone.23 As a result, the histopathologic findings of early MF mimic numerous benign inflammatory conditions,23,24 and a rapid and correct histologic diagnosis is not always possible. In this setting, molecular studies such as the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for the T-cell receptor will identify a clonal T-cell population in 50% to 80% of patients who ultimately develop overt histologic evidence of MF.25,26 To improve the diagnostic accuracy of early MF, the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphoma proposed a points-based algorithm for early diagnosis27 (Table 77-1).

TABLE 77-1 Proposed Algorithm for Diagnosis of Early Mycosis Fungoides

| Criteria | Score |

|---|---|

| Clinical | 2 points for basic + two additional criteria 1 point for basic + one additional criterion |

| Basic | |

| Persistent and/or progressive patches/thin plaques | |

| Additional | |

| 1. Non–sun-exposed location | |

| 2. Size/shape variation | |

| 3. Poikiloderma* | |

| Histopathologic | 2 points for basic + two additional criteria 1 point for basic + one additional criterion |

| Basic | |

| Superficial lymphoid infiltrate | |

| Additional | |

| 1.Epidermotropism without spongiosis | |

| 2.Lymphoid atypia† | |

| Molecular Biologic | 1 point for clonality |

| Basic | |

| Clonal T-cell receptor gene rearrangement | |

| Immunopathologic | 1 point for one or more criteria |

| 1.<50% CD2+, CD3+, and/or CD5+ T cells | |

| 2.<10% CD7+ T cells | |

| 3.Epidermal/dermal discordance of CD2, CD3, CD5, or CD7‡ | |

| Four or more points satisfy criteria for a diagnosis of early MF. | |

* Poikiloderma is defined as the combination of skin atrophy, telangiectasia, and mottled pigmentation.

† Lymphoid atypia is defined as cells with enlarged, hyperchromatic nuclei and irregular or cerebriform nuclear contours.

‡ T-cell antigen deficiency confined to the epidermis.

Adapted from Pimpinelli N, Olsen EA, Santucci M, et al: Defining early mycosis fungoides. J Am Acad Dermatol 53:1053-1063, 2005.

Biologic Characteristics and Molecular Biology

A malignant clone in patch-plaque MF bears the immunophenotype of activated, skin-homing CD4+ helper T cells.18 When a naïve T cell identifies its cognate antigen in a skin-draining lymph node, activation occurs, and the T cell begins to express cutaneous lymphocyte antigen (CLA) and CC chemokine receptor 4 (CCR4). As these activated T cells pass through the capillaries of inflamed skin, CLA and CCR4 bind to their respective ligands on the dermal capillaries, resulting in extravasation of the activated T cells into the dermal connective tissue. Once outside the circulation, activated T cells migrate to the epidermis and interact with antigen-presenting dendritic (Langerhans) cells (Fig. 77-1).

Clinically, progression of MF is associated with loss of epidermotropism and increasing tumor burden. Molecular studies have shown that progression of MF is associated with TP53 mutation,28 numerous chromosomal rearrangements,29 and microsatellite instability.30 In addition, the malignant cells in MF develop mechanisms to escape destruction by the host immune system. For example, although benign activated T cells are eliminated by fas/fas-ligand-mediated apoptosis, the malignant T cells of MF evade fas-mediated apoptosis via fas downregulation, mutation, or alternative splicing.31

As a malignant disease of the immune system, MF results in substantial alteration of host immunity with consequent increased risk of infection32 and possibly secondary malignant disease.33 For example, in patients with Sézary syndrome, the absolute number of normal circulating T cells often drops dramatically, reaching levels typically seen only in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome.34 In addition, malignant CD4+ T cells produce large amounts of interleukin-10 and transforming growth factor-β, resulting in further suppression of cell-mediated immunity.35,36 The malignant cells of MF also produce large amounts of soluble interleukin-2 receptor, which can inactivate interleukin-2,37 a cytokine needed to promote normal T-cell activation. Finally, the malignant cells of Sézary syndrome can elaborate large amounts of interleukin-4 and interleukin-5, producing a syndrome characterized by atopy and eosinophilia.36

Pathology and Pathways of Spread

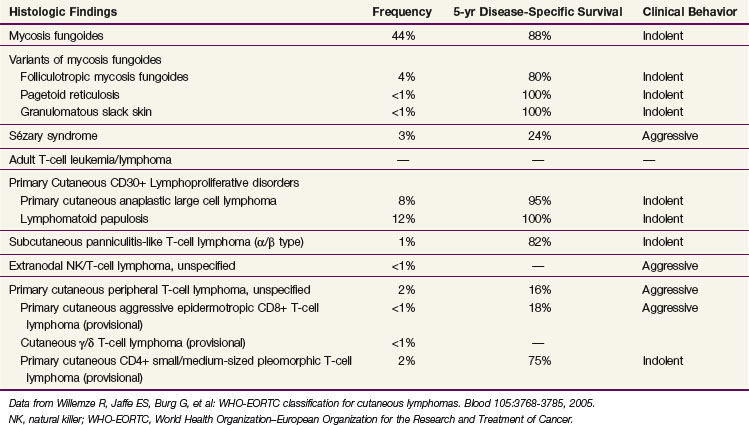

The diagnosis of MF remains challenging, even for the experienced clinician and dermatopathologist, due to both the absence of a diagnostic gold standard and the number of benign inflammatory dermatoses that may mimic MF, particularly in its early stages. Currently, the diagnosis relies upon integrating the clinical presentation with the histopathologic, immunophenotypic, and genotypic data. The current World Health Organization–European Organization for the Research and Treatment of Cancer (WHO-EORTC)38 pathologic classification scheme for CTCL is presented in Table 77-2.

Histopathology

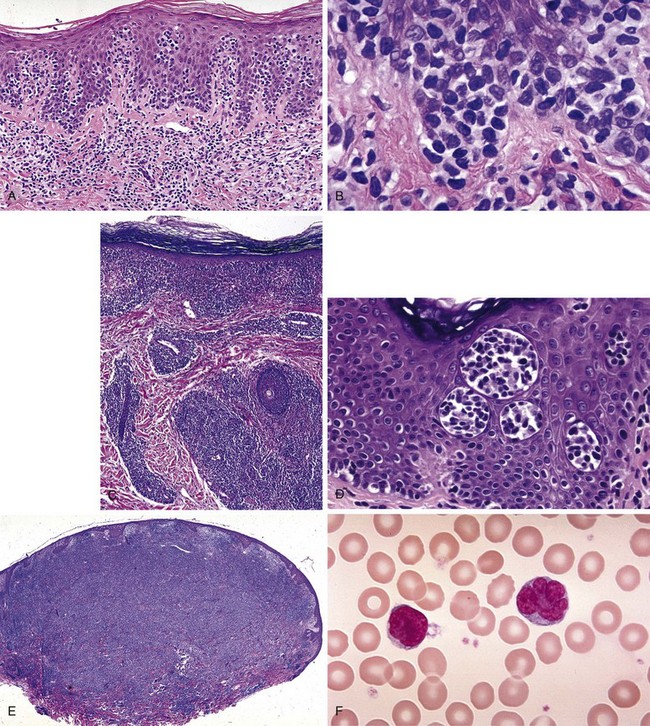

The most striking finding of early MF is profound epidermotropism, characterized by lymphocytes clustered along the basement membrane of the epidermis39 (Fig. 77-2A and B). Microdissection studies have shown that virtually all of the lymphocytes in the epidermis belong to the malignant clone, whereas most dermal lymphocytes are reactive.40,41

Several microscopic findings help to discriminate early MF from benign inflammatory mimics. For example, an EORTC study reported that identification of epidermal lymphocytes with extremely convoluted, medium to large (7 to 9 µm) nuclei enabled a correct diagnosis of MF with 100% sensitivity and 92% specificity24 (see Fig. 77-2B). In contrast, a study from Stanford University found that intraepidermal atypical lymphocytes surrounded by a clear halo (an artifact of fixation) were the most robust indicator of MF in a multivariate model.42 Another finding, Pautrier’s microabscess, is considered pathognomonic but is seen in less than 20% of early lesions42 (see Fig. 77-2D). Efforts are currently under way to establish a grading system to standardize pathology reporting and improve diagnostic accuracy.23,43

As MF progresses from the patch to plaque stage, the lymphoid infiltrate increases in density and begins to invade the deeper reticular dermis (see Fig. 77-2C). Furthermore, due to the increased burden of neoplastic cells, findings such as Pautrier’s microabscesses (see Fig. 77-2D), haloed lymphocytes, and convoluted nuclei are more readily identified, resulting in improved diagnostic accuracy. Tumor formation results from vertical growth of the lymphoid infiltrate and may be associated with complete loss of epidermotropism and sparing of the upper papillary dermis (see Fig. 77-2E). Erythrodermic MF often resembles patch-stage MF, although epidermotropism may be more subtle and neoplastic cells may be quite sparse.44

Immunophenotyping of Skin Lesions

Assessment of T-cell marker expression within the lymphoid infiltrate provides additional information that helps to establish a diagnosis of MF. The hallmark of MF is expression of CD4, the marker of mature helper T cells. A typical immunophenotype for MF is CD2+ (pan T cell), CD3+ (pan T cell), CD4+ (helper T cell), CD5+ (pan T cell), CD45RO+ (memory T cell), CLA+ (cutaneous lymphoid antigen), CD8− (cytotoxic T cell), CD30− (activated T cell).45 Although many benign dermatoses express a similar immunophenotype, two markers, CD7 and Leu-8, are often underexpressed in MF and may be helpful in distinguishing between MF and benign mimics. Finally, rare cases of apparently classic MF that are CD4− but CD3+ and CD8+ have been reported.46

T-Cell Receptor Gene Rearrangement

Clonal T-cell receptor gene rearrangements are frequently identified in MF skin lesions and may help to differentiate between early MF patches and benign mimics. Clinical data indicate that PCR will identify a dominant clonal T-cell receptor-γ rearrangement in 63% to 90% of skin biopsies that show definite histologic evidence of MF.47,48 Furthermore, PCR identifies a clonal T-cell population in 50% to 80% of histologically borderline biopsies obtained from patients who subsequently develop classic MF.25,26 In contrast, T-cell clonality occurs in only 6% to 24% of benign dermatoses that contain a lymphoid infiltrate.47,48 These observations suggest that identification of a clonal T-cell population should always be considered in light of the clinical and histologic context and may help to confirm a diagnosis of MF when it is already suspected on these grounds.

Transformation to Large Cell Histologic Variant

Transformation to a large cell variant occurs in up to 39% of patients initially diagnosed with MF.49 Histologic diagnosis of transformation can be made when large cells (four times or more the size of a small lymphocyte) make up more than 25% of the lymphoid infiltrate or form microscopic nodules.50 Transformation is associated with expression of CD30 in 30% of cases and expression of CD20 in 45% of cases. Transformed MF is typically aggressive, with clinical behavior similar to that of high-grade lymphoma.

Clinical Manifestations

According to the EORTC classification of cutaneous lymphomas, the term mycosis fungoides should be reserved for those CD4+ cutaneous lymphomas that are “characterized by the subsequent evolution of patches to more infiltrated plaques and eventually tumors.”2 Over time, MF may spread to involve lymph nodes, blood, bone marrow, and visceral organs. Symptoms may vary by degree of involvement, but weight loss, night sweats, and fever are uncommon unless infection is present.

Premycotic Phase

Early MF typically begins with mildly erythematous, slightly scaling, annular or arcuate macules that classically involve sun-shielded areas (Fig. 77-3A). These lesions may wax and wane for years before histologic findings show definitive evidence of MF.

Plaque Phase

If untreated, some patches will progress to form more generalized, deeply infiltrative, scaling plaques that often have well-demarcated, palpable borders and may exhibit central clearance and arcuate morphologic characteristics (see Fig. 77-3B). Associated findings include hyperkeratosis of the palms and soles and fissures.

Tumor Phase

Over 80% of tumors emerge in the setting of established patch-plaque MF (see Fig. 77-3C). The most common sites of tumor involvement include the face, digits, and perineum. Tumors frequently ulcerate and are prone to infection.

Tumeur d’Emblée

The term tumeur d’emblée refers to the rare patient who presents with tumors that arise in the absence of antecedent skin lesions; some cases may be more appropriately classified as CD30− cutaneous large T-cell lymphoma rather than MF.51 The clinical course may be more aggressive than that of classical MF.

Erythroderma

Erythroderma is defined as greater than 80% body surface involvement with confluent patches and/or plaques. It is associated with intense pruritus, hyperkeratosis of the palms and soles, skin atrophy, and lichenification (see Fig. 77-3D). Erythroderma may arise de novo or from progression of patch/plaque MF.

Lymph Nodes

Lymph node involvement is present in 15% of newly diagnosed patients and is associated with advanced cutaneous disease.52 Nodes are typically nontender and mobile and measure from 1 to 4 cm. Bulky adenopathy is uncommon.

Internal Organs

Visceral involvement is typically seen only in patients with advanced cutaneous disease, nodal disease, and blood involvement. The most common sites include the lungs, central nervous system, oral cavity, and oropharynx,52,53 although MF has been observed in other sites such as the breast, thyroid, and pancreas. Visceral involvement is often subclinical and does not routinely precipitate death. Bone marrow involvement at initial staging has been reported in 6% to 28% of patients and is also associated with advanced skin and nodal disease.54,55

Sézary Syndrome

Sézary syndrome (SS) is defined as erythroderma plus evidence of malignant circulating T cells that satisfy any of the five criteria56 listed in Table 77-3. For the purposes of these criteria, the Sézary cell is defined as “any atypical lymphocyte with [a] moderately to highly infolded or grooved nucleus”56 (see Fig. 77-2F). Clinical findings may include edema and tumorous involvement of the face leading to leonine facies, severe fissures of the palms and soles, intense pruritus, and cutaneous pain.

TABLE 77-3 Proposed Hematologic Criteria for Diagnosis of Sézary Syndrome

| Absolute Sézary cell count ≥1000 cells/µL. |

| CD4/CD8 ratio ≥10 due to an increase in CD3+1 or CD4+1 cells by flow cytometry. |

| Aberrant expression of pan-T-cell markers (CD2, CD3, CD4, CD5) by flow cytometry. Deficient CD7 expression on T cells (or expanded CD4+1, CD7− cells ≥40%) is a tentative criterion. |

| Increased lymphocyte count with T-cell clone in blood identified by Southern blot or polymerase chain reaction. |

| A chromosomally abnormal T-cell clone. |

Adapted from Vonderheid EC, Bernengo MG, Burg G, et al: Update on erythrodermic cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Report of the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas. J Am Acad Dermatol 46:95-106, 2002.

Variants of Mycosis Fungoides

The progression from subtle patches to indurated plaques, cutaneous tumors, and erythroderma represents classical so-called Alibert-Bazin mycosis fungoides. According to the EORTC classification, variants such as bullous and hyperpigmented or hypopigmented MF manifest similar clinical behavior and should not be considered separately from classical MF.2 Several variants sharing some clinical and pathologic features with MF have been described.

Folliculotropic Mycosis Fungoides

This entity presents with follicular papules, comedo-like lesions, milia-like lesions, patches, and plaques, all of which may produce alopecia.1,38 Although it typically involves the head and neck, any skin site may be affected.2 Pathologically, atypical lymphocytes invade follicles and may deposit acid mucopolysaccharides in the pilosebaceous units. Folliculotropic MF tends to be refractory to topical treatments such as PUVA and nitrogen mustard, and risk of relapse after treatment with TSEBT appears to be higher when compared with that of patients with classical MF.57 The 5-year disease-specific survival (DSS) is approximately 80%.38

Pagetoid Reticulosis or Woringer-Kolopp Disease

Pagetoid reticulosis, also known as Woringer-Kolopp disease, typically presents as a slow-growing, hyperkeratotic or psoriasiform, localized patch or plaque involving a distal extremity. Pathologically, an abundant epidermotropic infiltrate composed of atypical large lymphocytes is noted, along with pagetoid spread of individual lymphocytes interspersed among keratinocytes. Benign-appearing small lymphocytes are found in the upper dermis.1 The prognosis for localized pagetoid reticulosis is excellent with either surgery or radiotherapy, and disease-related deaths have not been reported.2,38 Ketron-Goodman type is a disseminated, more aggressive cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorder that histologically resembles localized pagetoid reticulosis.

Granulomatous Slack Skin

This rare variant presents with lax skin in the axillae, neck, breasts, and inguinal regions. Histologic features include epithelioid or giant cell dermal granulomas and associated destruction of elastin fibers.2 Notably, Hodgkin’s disease has been associated with granulomatous slack skin in roughly one-third of reported cases.58 Because of its rarity, optimal treatment has not been established.

Related Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoproliferative Disorders

Primary Cutaneous Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma or CD30+ Large Cell Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma

This entity typically presents as a red or flesh-colored nodule or tumor that frequently ulcerates. Histopathologic testing shows sheets of CD30+ large lymphocytes without epidermotropism. In contrast to systemic CD30+ anaplastic large cell lymphoma, overexpression of anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) is not found in primary cutaneous CD30+ large cell lymphoma. Patients with localized disease are typically treated with radiotherapy alone, and the prognosis is excellent, with a 5-year DSS of approximately 90% to 95%.2,59,60

Lymphomatoid Papulosis

Lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP) presents with grouped erythematous or violaceous papules and/or nodules at different stages of development. Lesions typically resolve spontaneously within 2 to 8 weeks, but scarring is common.61 Three different histologic subtypes have been described, with types A and C consisting of malignant CD30+ T cells, often with an extensive inflammatory infiltrate, and type B simulating classical plaque-stage MF. For type C lesions, discrimination between LyP and CD30+ large cell lymphoma may be difficult on histologic grounds, and assessment of the clinical context may be required to ensure the proper diagnosis.2 Although cytologically malignant, it should be emphasized that LyP is clinically benign, with a 5-year survival rate of 100%.2,38,59 Neither aggressive chemotherapy nor radiotherapy are therefore indicated.62 Treatment options include PUVA or low-dose methotrexate, but neither is considered curative. In the long term, at least 15% to 20% of patients with LyP will develop a secondary malignant tumor, most commonly MF, CD30+ large cell lymphoma, or Hodgkin’s disease.62,63 In patients undergoing TSEBT for MF, a history of LyP is associated with an increased risk of relapse.57

Adult T-Cell Lymphoma or Leukemia

Adult T-cell lymphoma/leukemia (ATLL) develops in 2% to 4% of individuals infected with human T-cell lymphotrophic virus type I (HTLV-I), a retrovirus endemic in southern Japan and the Caribbean.1,61,64,65 Skin findings are present in up to 60% of patients with ATLL and strongly resemble those of MF, including plaques, tumors, and erythroderma. The characteristic immunophenotype is CD2+ CD3+ CD4+ CD5+ CD7− CD8− and the malignant cells strongly express the high-affinity interleukin-2 receptor (CD25, CD122, and CD132). Clinical features vary from an acute form presenting with B symptoms, hypercalcemia, metabolic bone disease, hepatosplenomegaly, generalized adenopathy, and leukemic infiltration to a smoldering or chronic form presenting with skin infiltration and little or no systemic involvement. Although patients often respond to conventional chemotherapy, long-term survival is rare. Newer promising agents include denileukin diftitox66 and interferon-α in combination with zidovudine.67

Subcutaneous Panniculitis-like T-Cell Lymphoma (α/β Type)

In prior years, subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma was thought to run two markedly different clinical courses—an indolent course and an aggressive course. Recently, molecular studies have indicated that the indolent form of subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma is caused by CD8+ T cells that express the α/β T-cell receptor. This entity typically presents with subcutaneous nodules or plaques involving the legs or trunk and has a 5-year DSS of approximately 82%.38 In contrast, the more aggressive form of subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma is caused by CD8− T cells that express the γ/δ T-cell receptor and is now classified as cutaneous γ/δ T-cell lymphoma in the updated WHO-EORTC system.38 This entity is often fatal and complicated by hemophagocytic syndrome. Treatment for the α/β type is often observation, whereas treatment for the γ/δ type includes combination chemotherapy and possibly cyclosporine.1,2

Prognosis and Staging

The seventh edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system for MF identifies the extent and character of skin lesions, extracutaneous disease, and leukemic transformation as the major predictors of poor prognosis68 (Tables 77-4 and 77-5). Shortcomings of this system include (1) difficulty in assigning T category for patients who fall on the border between T1 and T2; (2) failure to discriminate between the prognosis of patients with extensive patches as compared with extensive plaques; (3) similarity in prognosis between patients with tumors and erythroderma; (4) the questionable prognostic relevance of enlarged, pathologically uninvolved lymph nodes; and (5) the rarity of the N2 descriptor because biopsies of nonpalpable lymph nodes are seldom performed.69,70 To address these shortcomings, the EORTC, in conjunction with the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphoma, recently proposed a new staging system for MF, though it remains to be seen how this proposal will affect subsequent iterations of the AJCC staging system.71

TABLE 77-4 TNM(B) Classification for Mycosis Fungoides

| T1 | Patches and/or plaques involving <10% body surface area |

| T2 | Patches and/or plaques involving ≥10% body surface area |

| T3 | One or more cutaneous tumors |

| T4 | Generalized erythroderma |

| N0 | Lymph nodes clinically uninvolved |

| N1 | Lymph nodes clinically enlarged but histologically uninvolved |

| N2 | Lymph nodes clinically nonpalpable but histologically involved |

| N3 | Lymph nodes clinically enlarged and histologically involved |

| M0 | No visceral disease present |

| M1 | Visceral disease present |

| B0 | No circulating atypical cells (<1000 Sézary cells [CD4+1 CD7–]/µL) |

| B1 | Circulating atypical cells present (≥1000 Sézary cells [CD4+1 CD7–]/µL) |

Adapted from Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al: AJCC Cancer Staging Handbook, 7th ed. New York, Springer, 2010.

TABLE 77-5 Staging Classification for Mycosis Fungoides*

| IA | T1N0M0 |

| IB | T2N0M0 |

| IIA | T1-2N1M0 |

| IIB | T3N0-1M0 |

| IIIA | T4N0M0 |

| IIIB | T4N1M0 |

| IVA | T1-4N2-3M0 |

| IVB | T1-4N0-3M1 |

* The B descriptor is not considered in stage classification.

Adapted from Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al: AJCC Cancer Staging Handbook, 7th ed. New York, Springer, 2010.

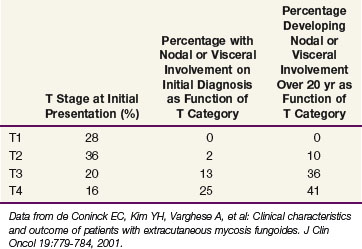

Data from a cohort of 468 patients with newly diagnosed MF evaluated at Stanford University52 are presented in Table 77-6. Over 60% of patients presented with patches and/or plaques without nodal or visceral disease. Such patients rarely developed disseminated disease, even at 20 years of follow-up. In contrast, 50% to 60% of patients presenting with tumors or erythroderma will develop extracutaneous disease.

TABLE 77-6 Initial Stage and Natural History of 468 Patients with Mycosis Fungoides Evaluated at Stanford University at the Time of Initial Diagnosis

Data from Stanford University showed that patients with limited patches and plaques (IA, T1N0M0) experience 10-year survival rates similar to those of a matched control population. In contrast, the median survival time for patients with extensive patches and plaques (T2), tumors (T3), and erythroderma (T4) was 11, 3.2, and 4.6 years, respectively.72 Patients with either pathologically documented lymph node involvement or visceral involvement experienced a median survival time of roughly 1 year.52

A multi-institutional study showed that survival time is also related to the pattern and extent of lymph node involvement.73 For example, partial or complete effacement of nodal architecture by malignant lymphocytes conferred a median survival time of 2.3 years. In contrast, lymph nodes with aggregates of atypical lymphocytes but preserved nodal architecture resulted in a median survival time of 6 years and lymph nodes with only dermatopathic changes or few atypical lymphocytes resulted in a median survival time of 9 years.

Other factors that may herald a poor prognosis include patient age of 60 years or more,74 elevated LDH levels,74 elevated soluble interleukin-2 receptor levels,37 a low percentage of CD8+ tumor infiltrating lymphocytes,75 extent of skin involvement in those with T3 disease,76 T-cell clonality within the cutaneous infiltrate detected by PCR,77,78 an identical T-cell clone in the skin and peripheral blood,79 and T-cell clonality in dermatopathic lymph nodes.80

The AJCC also included a blood descriptor, B0 versus B1, to document the absence or presence of more than 1000 Sézary cells (CD4+, CD7− per µL). Among patients with erythroderma, the presence of B1 disease is a significant, independent predictor of survival time, doubling the risk of death.81

For those patients with transformation to a large cell variant of MF, the median survival time ranges from 19 months to 36 months.49,50 Factors predictive of poor survival after transformation include a short interval between the diagnosis of MF and transformation (<2 years) and the presence of IIB to IV disease.49

Patient Evaluation

History

All patients should have a thorough history performed by the evaluating dermatologists, radiation oncologists, and any other consultants (Table 77-7). Careful attention should be given to the duration, change in appearance, and distribution of the eruption according to the patient. Inquiry related to a history of pruritus, pain, exfoliation, fissures, bullae, and perineal discomfort should be made. Previous diagnostic considerations, procedures, and therapies should be recorded in detail to establish temporal relationships. The clinical interview, along with the examination, are the two most important aspects of the workup because they can help exclude other diagnoses and establish whether the narrative and findings are consistent with a diagnosis of MF.

TABLE 77-7 Recommended Workup for Patients with Suspected Mycosis Fungoides

CBC, complete blood count; CT, computed tomography; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; PET, positron emission tomography.

Diagnostic Testing

Pathology

Routine bone marrow examination is generally unnecessary but may be considered in patients with blood or other visceral involvement. Bone marrow involvement at initial staging has been reported in 6% to 28% of patients and is associated with advanced skin and nodal disease.54,55 There is no evidence to suggest that marrow involvement is an independent predictor of outcome, however.55,74 Furthermore, although a clonal T-cell population within the marrow is identified in 75% of patients with identical skin and peripheral blood T-cell clones, this finding does not appear to alter the prognosis.54

Hematology and Chemistry

A thorough examination of the peripheral blood for evidence of malignant T cells is indicated for those with IIB to IV MF and may be considered for those with IA to IIA disease. Peripheral blood flow cytometry should be performed to assess expression of CD2, CD3, CD4, CD5, CD7, CD8, CD20, and CD45RO. Findings suggestive of blood involvement include an elevated CD4 : CD8 ratio (normal range, 0.5 to 3.5), or an expanded population of CD4+D7− or CD45RO+ lymphocytes.56 If initially abnormal, findings on peripheral blood flow cytometric testing should be followed to assess the response to therapy. If flow cytometry is unremarkable, peripheral blood PCR for T-cell receptor gene rearrangement should be considered. PCR reveals a clonal T-cell population identical to that found in the cutaneous infiltrate in 40% of patients with erythroderma and 14% of patients with patches, plaques, or tumors.47

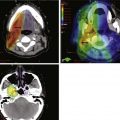

Diagnostic Imaging

Chest radiography should be completed for all patients via posteroanterior and lateral views. CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis may be obtained for patients with tumors, erythroderma, or nodal involvement but is not necessary for those with IA or IB disease given the low yield.82 FDG-PET (fluorodeoxyglucose–positron emission tomography) may also be beneficial for patients with advanced skin disease; for example, Stanford University reported that CT alone identified pathologic adenopathy by size criteria in only 5 of 13 patients, whereas the addition of PET identified hypermetabolic adenopathy in 13 of 13 patients. The standardized uptake value (SUV) of the FDG correlated with the extent of nodal involvement, with the highest SUVs noted in patients with complete nodal effacement and large cell transformation.83 To confirm nodal involvement and document the presence or absence of transformation, excisional biopsy should be strongly considered for selected abnormal lymph nodes that are radiographically identified.

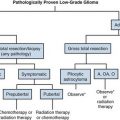

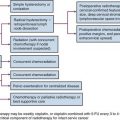

Primary Therapy

Because MF is a disease of cutaneous (i.e., skin-homing) lymphocytes, therapy is quite distinct from that of nodal lymphomas. For patients with disease limited to the skin, topical therapy alone produces high rates of remission and even cure. Topical therapies include mechlorethamine (nitrogen mustard), carmustine (BCNU), steroids, bexarotene gel, psoralen plus ultraviolet A (PUVA), ultraviolet B (UVB), and either localized or total skin electron radiotherapy. For patients with localized unilesional MF, topical therapies alone produce long-term DFS in excess of 85%.19–21 For those with more than one patch or plaque but with less than 10% body surface area involvement (T1N0 and T1N1), topical therapies alone produce long-term DFS ranging from 30% to 50%. For patients with more extensive patches or plaques, topical therapies may produce remission, but long-term cure is unlikely. Such patients should receive intensive topical therapy to induce a complete remission followed by less intensive adjuvant topical therapy to sustain a remission.84,85

Those with tumors or erythroderma experience severe cutaneous symptoms and are at high risk for extracutaneous dissemination. Of all the topical therapies, total skin electron beam therapy (TSEBT) is associated with the highest rates of complete response for this patient subgroup.85–87 Therefore it is recommended that TSEBT be administered to induce cutaneous remission and that adjuvant systemic and/or topical therapy be administered to sustain remission. Systemic therapies include interferon, retinoids, oral bexarotene, denileukin diftitox, vorinostat, extracorporeal photochemotherapy (photopheresis), and cytotoxic chemotherapy.

Skin-Directed Therapy

Mechlorethamine

Topical mechlorethamine hydrochloride (HN2), also known as nitrogen mustard, is an alkylating agent with proven activity in the treatment of MF patches and plaques. Mechlorethamine is typically applied daily and continued for at least 6 months after a complete response.69 Cutaneous intolerance, manifested by erythema and pruritus, occurs in roughly 50% of patients treated with aqueous HN2,88 but is reduced to less than 10% in patients treated with HN2 dissolved in ointment such as Aquaphor.69 Other cutaneous side effects of HN2 may include xerosis, hyperpigmentation, and, rarely, bullous reactions, urticaria, and Stevens-Johnson syndrome.88

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree