Multiple Myeloma and Plasmacytomas

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The incidence of plasma cell tumors is now approximately the same as that for Hodgkin’s disease and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (2 to 3 per 100,000).

NATURAL HISTORY

Plasma cell neoplasms are associated with proliferation and accumulation of immunoglobulin-secreting cells derived from B-cell lymphocytes.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Common presenting complaints include bone pain (68%), infection (12%), bleeding (7%), and easy fatigability (53).

Peripheral blood examination usually reveals anemia.

Thrombocytopenia, granulocytopenia, or both are present in one third of patients.

Hyperglobulinemia can cause disturbances of the clotting mechanism.

Hypercalcemia is present in 50% of patients. Skeletal radiographs demonstrate one of three common patterns: diffuse osteoporosis, well-demarcated lytic lesions, or localized cystic osteolytic lesions.

Plasma cell tumors secrete a measurable “paraprotein” in 95% to 99% of cases.

Immunoglobulin G is found in 50% to 60% of cases and immunoglobulin A in 20% to 25%.

Solitary Plasmacytoma

Solitary plasmacytomas, which are localized lesions of bone (80% are osseous) or soft tissue (20% are extramedullary), account for 2% to 10% of all plasma cell tumors (24, 53).

Solitary plasmacytomas of bone most frequently involve the vertebral bodies or the pelvic bones. Most patients presenting with a solitary plasmacytoma of bone (SPB) ultimately develop myeloma (Fig. 42-1).

A second type of localized presentation occurs in soft tissue (extramedullary plasmacytoma). It arises most frequently (80%) in the upper aerodigestive tract (e.g., nasal cavity, nasopharynx, paranasal sinuses, larynx, tonsils), but is also found in the lung, lymph nodes, spleen, and gastrointestinal tract.

The rate of progression to multiple myeloma for osseous plasmacytoma and extramedullary plasmacytoma is 50% to 80% and 10% to 40%, respectively (26).

Survival is significantly better with extramedullary plasmacytoma than with myeloma. Wiltshaw (55) reports a 40% survival rate at 10 years.

DIAGNOSTIC WORKUP

Blood chemistries obtained include creatinine, total protein, albumin, lactate dehydrogenase, and c-reactive protein.

Serum and urine protein electrophoresis, along with 24-hour urinary protein excretion, are an essential part of the workup.

β2-Microglobulin is a low-molecular-mass protein that is a function of both myeloma cell mass and renal function. Therefore, the serum level (>4 to 6 mg per mL) has been useful in staging and prediction of survival.

A complete radiographic skeletal survey is more sensitive than bone scan with 99mTc in detecting bony lesions, as the bone lesions from myeloma are a purely lytic phenomenon (14).

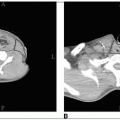

Localized areas of disease should be evaluated by computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). MRI is essential to assess the extent of myelomatous disease in certain disease sites, particularly in the spine where it can also detail the presence of spinal cord or nerve root compression.

Imaging with 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) has also been shown to be of benefit in assessing the functional definition of lesions seen with other modalities.

Significant advances in diagnostic imaging have likely resulted in a “stage migration” phenomenon (16).

Studies have shown that some patients with presumed osseous solitary plasmacytoma will be upstaged following the detection of multiple vertebral lesions or bone marrow disease by MRI and/or FDG-PET (32, 46).

A bone marrow aspiration and biopsy is needed to evaluate the extent of bone marrow infiltration and clonal proliferation of malignant plasma cells.

A commonly used system of diagnosis of multiple myeloma requires a specified combination of one major and one minor criteria, or three minor criteria, from the following:

Major criteria

Plasmacytoma on tissue biopsy

Bone marrow plasmacytosis with greater than 30% plasma cells

Monoclonal globulin spike on serum electrophoresis; IgG greater than 3.5 g per dL, IgA greater than 2.0 g per dL, light chain excretion on urine electrophoresis greater than 1.0 g per 24 hours in the absence of amyloidosis

Minor criteria

Bone marrow plasmacytosis with 10% to 30% plasma cells

Monoclonal globulin spike present, but lower levels than defined above

Lytic bone lesions

IgM less than 50 mg per dL, IgA less than 100 mg per dL, or IgG less than 600 mg per dL

Staging traditionally has been performed using the Durie and Salmon staging system (15).

A newer validated staging system, the International Myeloma staging system, which is less complex, will be of particular importance for current and future clinical trials (23).

PROGNOSTIC FACTORS

In a Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG) review of prognostic parameters in 482 patients with myeloma, factors associated with a shortened survival or remission duration were old age, severe anemia, hypercalcemia, blood urea nitrogen greater than 40 mg per dL, markedly elevated M protein, hypoalbuminemia, and high tumor cell burden (2).

The most easily measurable, quantifiable, and strongest prognostic factors are the serum β2-microglobulin (greater than 2.5 mg per L) and low serum albumin levels (7).

GENERAL MANAGEMENT

Solitary Plasmacytoma

Radiation is the primary therapy for osseous solitary plasmacytoma. Surgery is only considered in the case of structural instability or cord compression with rapid neurologic decline (49).

Even for those patients treated with surgery, postoperative radiation is still indicated secondary to a high likelihood for residual microscopic disease leading to an increased rate of local recurrence (38).

The local control rate with radiation is 80% to 95%; however, survival with radiation alone is only 50% at 10 years. The reason for the discrepancy is the high rate of progression to multiple myeloma seen with osseous plasmacytomas, generally from 50% to 80% at a median of 2 to 3 years (17, 54).

About 30% to 50% of patients with apparent solitary plasmacytoma will have multiple asymptomatic lesions detected in the spine on MRI (33, 37). If all the diagnostic criteria for solitary plasmacytoma are still met, the appropriate management is to give local radiation to the presenting site (47). These patients have a high risk of progression to myeloma, and chemotherapy can be started at the time of symptomatic progression.

A low-level M-protein at presentation is very common and is not associated with an increased progression rate to multiple myeloma. However, if it persists postradiation, there is a high rate of subsequent systemic failure (12, 18).

The use of adjuvant melphalan and prednisone (MP), though shown to have some benefit, is not routinely recommended because of concerns with the effects of long-term alkylating agent use (6).

Extramedullary plasmacytomas (EMPs) may be cured by surgery alone if they are small. For larger lesions, inoperable tumors, or residual disease, local radiation should be utilized.

The progression to myeloma for extramedullary plasmacytomas is much lower than for osseous plasmacytomas, approximately only 10% to 40%. Therefore, many patients are cured of their disease with local radiation alone (19, 48, 55).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree