Study (location, year)

MNG

SN

Diagnostic method

OR (CI)

Events

Population

Events

Population

Abu-Eshy et al. (Saudi Arabia, 1995)

14

172

16

105

Surgery

0.49 (0.23–1.06)

Belfiore et al. (Italy, 1992)

49

1152

211

4485

Surgery

0.86 (0.62–1.19)

Deandrea et al. (Italy, 2002)

12

174

15

246

FNA

1.14 (0.52–2.50)

Edino et al. (Nigeria, 2010)

24

160

1

13

Surgery

2.12 (0.26–17.05)

Franklyn et al. (UK, 1993)

1

72

19

321

FNA

0.22 (0.03–1.70)

Frates et al. (USA, 2006)

119

804

175

1181

FNA

1.00 (0.78–1.29)

Khairy et al. (Saudi Arabia, 2004)

16

124

24

172

Surgery

0.91 (0.46–1.80)

Marqusee et al. (USA, 2000)

8

90

4

60

FNA

0.37 (0.39–4.75)

Matesa et al. (Croatia, 2005)

15

289

6

117

FNA

1.01 (0.38–2.68)

McCall et al. (USA, 1986)

9

69

16

96

Surgery

0.75 (0.31–1.81)

Papini et al. (Italy, 2002)

13

207

18

195

FNA

0.66 (0.31–1.38)

Rago et al. (Italy, 2010)

411

19,923

446

13,549

FNA

0.62 (0.54–0.71)

Sachmechi et al. (USA, 2000)

9

92

4

50

FNA

1.25 (0.36–4.27)

Taneri et al. (Turkey,2005)

35

237

24

133

Surgery

0.79 (0.45–1.39)

Total

733

23,565

979

20,723

0.80 (0.67–0.96)

Clinical Evaluation

Clinical evaluation includes assessment of symptoms’ severity and duration, family history of thyroid disorders or thyroid cancer, and a history of head and neck radiation. Age and gender can influence prognosis.

Clinical picture varies widely based on the location, extent, and function of the goiter. Frequently, small, nontoxic multinodular goiters are asymptomatic and found incidentally on routine physical examination or on imaging done for nonthyroid reasons such as carotid ultrasound, chest X-ray, magnetic resonance imaging, or CT of the neck and chest. Nontoxic MNG s can, at times, present with neck compressive symptoms such as neck pressure, cough, shortness of breath, and swallowing difficulty. Hoarseness of the voice in case of recurrent laryngeal nerve involvement is rare. Large goiters (Figs. 10.1 and 10.2) with retrosternal or mediastinal extension can produce tracheal deviation or compression, positional dyspnea, or thoracic outlet obstruction with certain maneuvers (Pemberton’s sign). Pain might be present in case of hemorrhage into a cystic nodule.

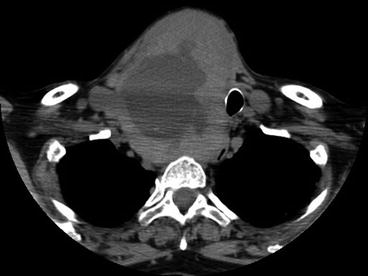

Fig. 10.1

CT scan of the neck and upper chest . Large MNG (arrow) deviating the trachea with mediastinal extension

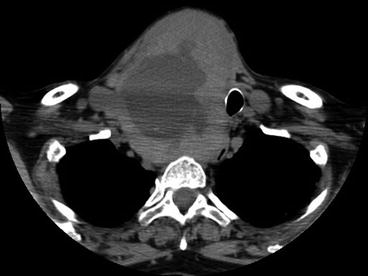

Fig. 10.2

CT scan of the neck. Large MNG compressing the trachea

The clinical picture in Plummer’s disease (toxic MNG) is variable ranging from subclinical to overt hyperthyroidism. Symptoms are associated with increased metabolic and adrenergic responses like heat intolerance, weight changes, nervousness, irritability, diaphoresis, palpitation, and tremor and signs like muscle weakness, tachycardia, increased tendon reflexes, lid lag, and/or retraction. In the elderly, however, the symptoms might not be as evident or may even be “masked” as in “apathetic hyperthyroidism.” Hyperthyroidism (subclinical or overt) can be present in up to 25% of patients with MNG [23].

Physical examination can detect thyroid enlargement with nodular irregularities. Neck palpation is imprecise in determining thyroid morphology and size [24]. In retrosternal goiter, fullness in the suprasternal notch can give a hint. There is no specific examination finding that can predict malignant nature of a goiter; however, hoarseness, rapid goiter growth, and cervical adenopathy are always concerning features, especially with positive family history or radiation exposure to the neck region.

Radiological characteristics of thyroid nodules should be carefully evaluated in order to select those that require further evaluation or fine needle aspiration.

Laboratory Investigation

There is no specific diagnostic laboratory pattern in patients with MNG. Sensitive TSH should be measured in all patients, and it may be normal, low, or even high. However, in most cases of MNGs, serum TSH is within the normal range [25]. Suppressed TSH (with normal or elevated serum FT4 level) is suggestive of toxic MNG (Plummer’s disease); this needs to be supported by diagnostic imaging. Additional testing, such as anti-thyroperoxidase (TPO) , has limited value in making the diagnosis of MNG but is helpful as elevated levels indicate autoimmune thyroid disease. Hashimoto disease may be associated with the presence of pseudo-nodules rather than true nodules on thyroid US; these are typically benign. Moreover, it might be associated with bilateral, enlarged, but benign-appearing lymphadenopathy . The routine measurement of serum thyroglobulin (Tg) or calcitonin (Ct) has no value in a patient with MNG. Serum Ct should be measured only with suspicion of MTC or if FNA is abnormal [26]. Measurement of serum TSH and Tg levels to assess malignancy risk of thyroid nodules is discussed later in this chapter.

Diagnostic Imaging

Different imaging modalities are available in evaluating toxic and nontoxic MNG, including neck ultrasonography (US) , computed tomography (CT) , magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) , thyroid scintigraphy , and positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) , though less frequently used.

Thyroid Ultrasonography (US)

High-resolution US is a widely used, inexpensive, and sensitive (≈95%) method to detect small, nonpalpable thyroid nodules (Fig. 10.3) and to complement neck palpation. Clinical practice has witnessed detection of more thyroid nodules in the United States and elsewhere [27]. An unintended consequence of US sensitivity has been the detection of incidental, and often insignificant, small solid or cystic thyroid nodules.

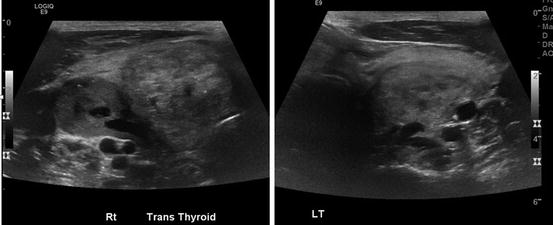

Fig. 10.3

Thyroid US small (sub-centimeter) nonpalpable thyroid nodules

All patients with suspected or confirmed thyroid nodules should have a full neck US to evaluate location, size, number, and other features of these. US can help identify thyroid nodules that need fine needle aspiration (FNA) and guide the FNA when needed (Fig. 10.4) [26, 28]. The importance of thyroid sonography is underscored by the fact that up to 50% of patients with single nodules on physical examination will show additional nodules [29]. However, the risk of malignancy is similar if nodules are single or multiple [21, 30, 31].

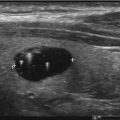

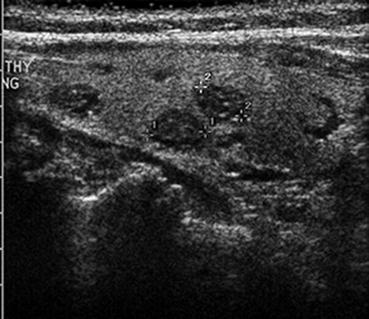

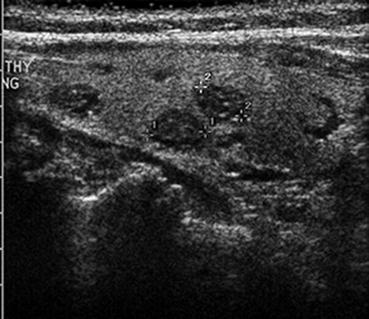

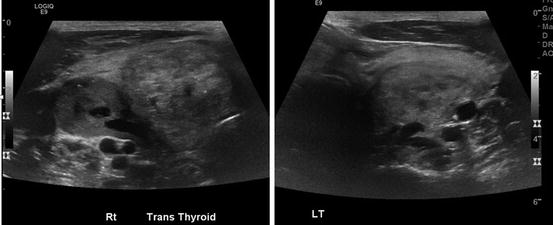

Fig. 10.4

Thyroid US large MNG with multiple heterogenous nodules with cystic changes on both sides

Computerized Tomography (CT) and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

Computerized tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provides better evaluation of thyroid size and extension in relationship to surrounding structure especially in patients with compressive symptoms and those with large goiter with suspected retrosternal extension (Fig. 10.5). However, these are not used routinely due to high cost. Of note, CT should be preferably used without contrast to avoid possible iodine-induced thyrotoxicosis in the setting of a MNG [23].

Fig. 10.5

CT scan of the neck and upper chest. Large MNG with huge nodule and central degeneration. There is evident tracheal compression and deviation with mediastinal extension

Thyroid Scintigraphy (Radioisotope Scan)

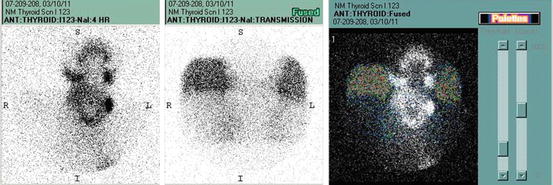

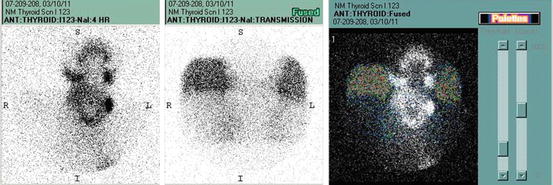

This test is not routinely ordered in evaluating MNG except when determining the functional status of thyroid nodule or MNG, associated with low serum TSH [32]. Thyroid scintigraphy can be performed using either technetium 99mTc pertechnetate or I123 scanning with sensitivities to detect functioning nodules about 91% and 83%, respectively [33]. Thyroid scan has low specificity (5–25%), due to interference from normal thyroid tissue with the radioisotope uptake. In the setting of a MNG, thyroid scan should always be done together with a neck US to help determine the need for FNA. Functioning nodules are not suspicious for malignancy and need not be subjected to FNA. Hot nodules account for fewer than 10% of all thyroid nodules and are almost always benign [25]. In toxic MNG, hot nodules trap the radioactive iodine (uptake), while this is inhibited in surrounding thyroid tissue giving the “patchy uptake” image suggestive of toxic MNG (Fig. 10.6).

Fig. 10.6

NM thyroid scans I123 showing enlarged gland with patchy uptake

FDG-PET-Positive Thyroid Nodule

In recent years, FDG-PET scanning is frequently performed for tumor staging and detection. When FDG-PET scan shows focal uptake in the thyroid bed, the risk of malignancy is high, around 35%; hence nodule warrants FNA [34–36]. On the other hand, diffuse FDG uptake in thyroid bed is suggestive of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis , which can be further evaluated with US but may not require FNA.

Fine Needle Aspiration Biopsy: FNA

Thyroid FNA is established as a safe, valuable, and cost-effective test in the diagnosis and treatment of nodular thyroid disease. In current practice, adequate samples should be obtained in 95% of cases [37, 38]. The use of US-guided FNA and on-site cytological examination can further reduce inadequate sampling [38–40]. Obviously, not all thyroid nodules require FNA. Selecting nodules that require FNA in MNG can be more challenging than in single nodules, because often more than one nodule needs FNA [21, 30, 31, 41]. In general, FNA is recommended for high US-risk thyroid lesions ≥10 mm, intermediate US-risk thyroid lesions >20 mm, and low US-risk thyroid lesions only when >20 mm, associated with high-risk history or increasing in size (Fig. 10.7) [26]. This applies also to glands with multiple nodules; however, it is seldom necessary to perform FNA in more than two nodules in a MNG. Additionally, it is not necessary to biopsy “hot” areas on radioisotope scan in the adult patient [26].

Fig. 10.7

(a) Benign thyroid nodule , Papanicolaou stain, 10× magnification: clusters of follicular cells with colloid and histiocytes in the background, suggestive of cystic degeneration (Image is courtesy of Heidi D. Lehrke, D.O.—pathology department-Mayo Clinic). (b) Papillary thyroid carcinoma, Papanicolaou stain, 40× magnification: clusters of epithelial cells with jumbled nuclei, nuclear grooves, and occasional pseudoinclusions (Image is courtesy of Heidi D. Lehrke, D.O.—pathology department-Mayo Clinic)

Management

Management is influenced by nodule or goiter growth, size and location of goiter, local and compressive symptoms, functional status, and risk of malignancy [42]. The choice of treatment depends on many issues, including patient’s comorbidities. Frequently, benign, small, asymptomatic, and nonfunctional goiters can be monitored with physical examination, TSH, and neck ultrasound without other intervention.

Nontoxic MNG and Toxic MNG

For patients with benign nontoxic MNG, the treatment mostly aims to decrease the size, relieve obstruction, or prevent further growth. Iodine supplementation was used as a therapeutic option in diffuse goiter associated with iodine deficiency in many countries worldwide; however, this has limited effect in treating multinodular goiter. Moreover, iodine load might induce subclinical/clinical hyperthyroidism (Jod-Basedow effect ).

The majority of goiters remain stable, while some may even regress [43]. Asymptomatic, euthyroid patient with nonobstructive MNG may require no intervention and can be monitored for further growth, obstruction, or autonomy. This can be done by following TSH, US, and possibly CT scans if indicated.

Surgery

Surgery is preferred to radioiodine therapy in patients with nontoxic, nonobstructive goiters that continue to grow and potentially cause obstructive symptoms or cosmetic concerns.

Near-total or total thyroidectomy should be performed for large or retrosternal goiters with obstructive symptoms (Fig. 10.8). After surgery, recurrence is seen in 10–20% in the first decade depending on the size of residual thyroid tissue [44]. Surgical complications are rare in experienced centers, but can be up to 10% since most surgeries are performed by general, low-volume surgeons [45], and include hypoparathyroidism, injury to trachea, or recurrent laryngeal nerves, especially in large and/or retrosternal goiters [46, 47]. When selecting surgery, one should consider risks and benefits in older patients, paying attention to those with significant comorbidities.