Cystic neoplasms of the pancreas represent a diagnostic challenge for physicians. Once considered rare, over the past two decades the identification of these cysts has increased secondary to the improvement and widespread use of cross-sectional imaging studies.1 A considerable proportion of these lesions are discovered incidentally in asymptomatic patients and are found with greater frequency in older populations.2,3

The significance of pancreatic cystic neoplasms (PCNs) lies in the spectrum of their underlying pathology. Since they were first distinguished from serous neoplasms in the late 1970s, mucinous pancreatic cystic neoplasms (MPCNs) have been extensively studied.4 Unlike serous cystic neoplasms (SCNs), MPCNs harbor the potential for malignant degeneration. Although the risk is higher in symptomatic patients, up to 47% of MPCNs are associated with malignant or premalignant lesions, making early detection and treatment essential.5,6

Mucinous pancreatic cystic neoplasms account for up to one-fourth of all PCNs and include two distinct classes of cysts. Besides their common underlying cancer risk and viscous quality, these MPCN variants possess distinct clinicopathologic features that dictate their presentation and behavior. Furthermore, the risk of malignant degeneration varies widely between subtypes.7 Within the broad category of MPCNs exists a spectrum of atypia, ranging from benign adenoma to grossly invasive cancer.

Mucinous cystic neoplasms (MCNs) are known to contain ovarian-type stroma and are almost exclusively found in women within the distal pancreas.8,9 In contrast, intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs) are mainly localized to the head of the pancreas and are characterized by intraductal proliferation of neoplastic cells whose phenotype and behavior are characterized by the type of ductal communication.8 Of the three IPMN variants, branch-duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (BD-IPMNs) account for the majority of all pancreatic cysts found incidentally and pose the biggest challenge for diagnosis and cancer risk stratification.10

The workup and diagnosis are critical in deciding the ultimate management of MPCNs. Although each cyst type is associated with a particular radiographic profile, imaging studies alone are often insufficient to render a diagnosis. Use of endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) with cyst fluid analysis has become an important tool to differentiate between cyst types and may be used in the diagnosis and surveillance of pancreatic cysts.11

Accurate diagnosis of pancreatic cyst types may ultimately prevent unnecessary resection by selecting those premalignant lesions that require intervention and those that may be closely observed. Over the last decade, international consensus guidelines have been developed with the intent to provide direction when managing patients with MPCNs.12,13 Correct identification and stratification of these entities is paramount to MPCN management and treatment.

The rising incidence of pancreatic cysts has been extensively reported in the literature. In one study, incidental pancreatic cysts were found in up to 13.5% of patients on routine magnetic resonance imaging.3 Furthermore, an autopsy study documented 186 cysts in 73 of 300 cases (24%).6 The prevalence and size of pancreatic cysts have also been demonstrated to increase with age and may be seen in up to 10% of patients 70 years or older.14

Pancreatic cysts may be congenital, inflammatory, or neoplastic. The majority of patients with pancreatic cysts are diagnosed with inflammatory pseudocysts. In fact, pancreatic pseudocysts may account for up to 85% of all pancreatic cystic lesions, secondary to the incidence of pancreatitis.15 However, only neoplastic cysts provide a significant threat of malignancy.

Pancreatic cystic neoplasms make up approximately 10% to 15% of all pancreatic cysts, and can be divided into serous neoplasms, mucinous neoplasms, solid pseudopapillary tumors, and other rare cystic entities (Table 148-1).7,16 The most common PCNs include serous cystadenomas (32% to 39%), MCNs (10% to 45%), and IPMNs (21% to 33%).1,17 Serous cystadenomas are essentially benign, and do not demonstrate any significant malignant potential. As such, much attention has been given to MCNs and IPMNs to better understand their nature and predict their behavior.

Classification of Pancreatic Epithelial Cystic Neoplasmsa

| Neoplastic | Non-neoplastic |

|---|---|

| Benign | |

| Serous adenoma (microcystic) | Congenital cyst |

| Serous adenoma (oligocystic, poorly demarcated) | Ductal retention cyst |

| MCN | Mucinous non-neoplastic cyst |

| IPMN | Enterogenous cyst |

| Acinar cell cystadenoma | Lymphoepithelial cyst |

| Dermoid cyst | Endometrial cyst |

| Cystic hamartoma | Periampullary duodenal wall cyst |

| Von-Hippel-Lindau-associated cystic neoplasm | |

| Borderline | |

| MCN | |

| IPMN | |

| Solid pseudopapillary tumor | |

| Malignant | |

| MCN-associated carcinoma | |

| IPMN-associated carcinoma | |

| Cystic ductal adenocarcinoma | |

| Serous cystadenocarcinoma | |

| Pancreatoblastoma | |

| Cystic metastatic epithelial neoplasm | |

| Cystic neuroendocrine carcinoma | |

Mucinous cystic neoplasms refer to a group of rare mucin-producing cysts found to comprise approximately 14% to 23% of all resected PCNs in large surgical series.18,19 They occur almost exclusively in middle-aged women and are usually seen in the fifth to seventh decades (mean age 48 years).20,21 Pancreatic MCNs are more commonly found in the body and tail of the pancreas as large macrocystic lesions, ranging from 2 to 25 cm in size (Table 148-2).22 Unlike the majority of PCNs that are discovered incidentally, patients with pancreatic MCNs often present with symptoms, which may be related to their larger size. Patients can present with vague abdominal pain, recurrent episodes of pancreatitis, abdominal fullness, nausea, or jaundice.5 Larger MCNs with associated symptoms have an increased risk of malignancy.20 Thus, symptomatic patients diagnosed with MCNs must be approached with a high index of suspicion.

Clinical Features of Mucinous Pancreatic Neoplasms

| MCN | MD-IPMN | BD-IPMN | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age of presentation (years) | 45–55 | 65–75 | 65–75 |

| Gender distribution (F:M) | >10:1 | 1:1 | 1:1 |

| Clinical presentation | Incidental, abdominal pain, or malignancy related | Incidental, pancreatitis, pancreatic insufficiency, malignancy related | Incidental, pancreatitis, pancreatic insufficiency, malignancy related |

| Imaging characteristics | Macrocystic, peripheral calcifications, no ductal communication | Macrocystic, dilated main pancreatic duct, possible gland atrophy | Macrocystic, dilated branch duct |

| Location/distribution | Body/tail | Diffuse | Diffuse |

| Pathologic findings | Tall, columnar mucin-producing epithelium, ovarian-type stroma | Multilocular, mucin-producing epithelium with papillae | Multilocular, mucin-producing epithelium with papillae |

| Malignant potential | Moderate | High | Low to moderate |

| Surgical indications | Resection | High-risk features MD dilation>10mm Worrisome Features: MD dilation 5–10 mm, change in duct caliber with distal atrophy | High-risk Features: Enhancing mural nodules, proximal lesion with jaundice Worrisome Features: size >3 mm, pancreatitis, non-enhancing mural thickening |

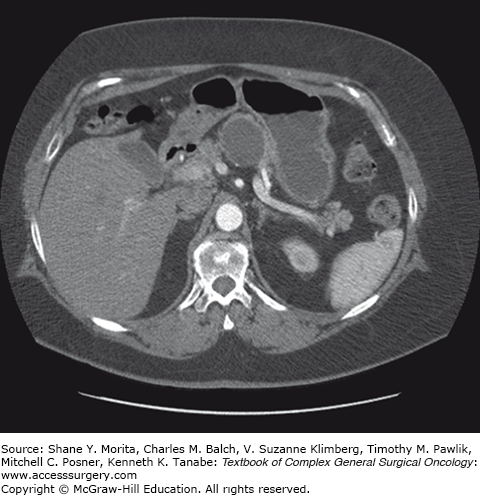

Radiographically, the classic MCN is a single, sphere-shaped macrocystic lesion in the distal pancreas, usually 8 to 10 cm in size (Fig. 148-1).23 On EUS examination they have thick, irregular walls and unlike IPMNs they do not communicate with the pancreatic ductal system. Although uncommon, these lesions may also contain peripheral egg-shell calcifications, and when present, these lesions are highly suspicious for malignancy.24,25 MCNs have been frequently mistaken for pancreatic pseudocysts in the past, but the absence of a surrounding inflammatory component differentiates them from pseudocysts. When confronted with any perimenopausal female patient found to have a macrocystic distal pancreatic cyst on computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), MCN must be high on the list of differential diagnoses regardless of the presence of a history of pancreatitis. Other findings on imaging studies that are concerning for an underlying premalignant or malignant process include mural nodules, associated masses, local invasion, or an asymmetrically thickened wall.9,25 In addition, increasing MCN cyst size and older age of the patient have both been recognized as risk factors for malignant degeneration.20 In fact, cysts greater than 8 cm in diameter have been proposed as a marker for malignancy in some studies.26,27 The absence of these risk factors, however, does not discount the malignant potential inherent to these lesions and should not be used as a stratification tool to guide treatment.

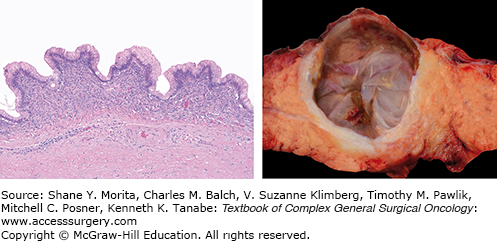

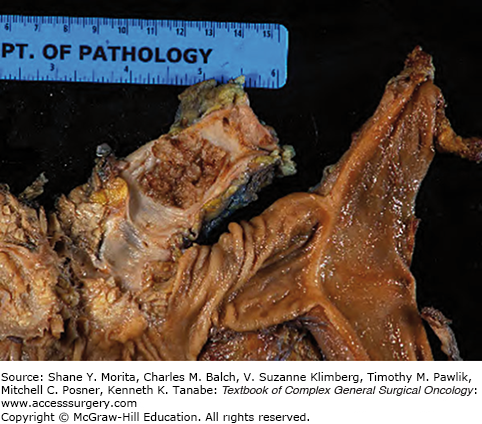

Macroscopically, MCNs are multilocular cysts with a smooth surface and a thick, fibrous pseudocapsule (Fig. 148-2). In larger lesions, the cyst wall may contain solid mural nodules.8 Cyst contents are often mucoid but may contain watery or hemorrhagic fluid. Microscopically, cysts are lined by tall, columnar mucin-producing epithelium. The pathognomonic ovarian-type stroma found lining the cyst walls and septae has become a requirement for the diagnosis of MCN.5,12 However, in larger cysts the epithelial lining can often be ablated making the ovarian stoma the only pathognomonic finding.

Mucinous cystic neoplasms possess a range of biological behavior, with varying degrees of malignant potential. It has been proposed that classification of these cysts aligns to three broad categories: (1) low-grade dysplasia, (2) moderate dysplasia, and (3) high-grade dysplasia. MCNs with low-grade dysplasia are lesions without atypia.8,13 These cysts are lined by flat, cuboidal to columnar epithelium with uniform nuclei and lack mitotic figures. The MCNs with mild to moderate atypia are classified as borderline tumors with moderate dysplasia.28 The epithelium found within these cysts is thick, often forming papillae, with occasional mitosis observed. MCNs with prominent papillae and severe cellular atypia are regarded as MCNs with high-grade dysplasia.8

Invasive carcinoma occurs in approximately one-fifth of all MCNs, ranging from 10% to 50% of all PCNs, and is encountered more frequently as the size and complexity of the lesions increase.28,29 Invasive carcinoma that develops in the setting of MCNs is frequently of the tubular or ductal type, and rarely found to be pure mucinous colloid carcinoma. The invasive component of an MCN can be very focal or patchy, with an abrupt transition from benign-appearing epithelium to cellular atypia or dysplasia.8 As such, analyzing multiple samples for a thorough histologic examination is required to exclude an invasive component. The cyst is classified based on the highest degree of atypia, not as an average.25

Mucinous cystadenocarcinomas represent the extreme in the adenoma to carcinoma sequence, ranging from approximately 4% to 12% of all MCNs.20,28,30 However, in some series, mucinous cystadenocarcinoma has been reported in up to 33% of cases.25 The discrepancy between series has been attributed to variations in pathologic tissue sampling.28 Although the prognosis for patients with mucinous cystadenocarcinoma is better than pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, 5-year survival rates are still approximately 33% to 56%.20,21,25 Like MCNs, the prognosis of mucinous cystadenocarcinomas has been linked to varying stages of invasion. In a recent study, only 1 out of 16 patients with mucinous cystadenocarcinomas with limited invasion to the ovarian stroma was found to have recurrence following resection after 48 months.31

The number of MCNs that progress to invasive carcinoma has been found to differ substantially between studies, depending on whether carcinoma in situ is included in this definition. As expected, without standardized categories for the inclusion of cyst types, comparisons between studies are difficult. According to World Health Organization classification, MCNs were once categorized as benign (mucinous cystadenoma), borderline (mucinous cystic neoplasm), or malignant (mucinous cystadenocarcinomas).32 This last category includes noninvasive lesions, or carcinoma in situ, in addition to invasive carcinoma. The differentiation between carcinoma in situ and invasive cancer is especially important in terms of patient prognosis and surveillance after resection. Currently, the term “high-grade dysplasia” has been suggested to replace “carcinoma in situ,” reserving this phrase for invasive carcinoma alone.13

Several genetic mutations have been investigated to explain the continuum of dysplasia found in MCNs. Point mutations within the K-ras oncogene have been well established in the pathogenesis of malignant transformation, as seen with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Accumulation of genetic mutations in the K-ras gene of MCNs were found to be proportionally higher with increasing severity of dysplasia.33 In addition, overexpression of p53 has been observed only in malignant MCNs in combination with mutated K-ras genes. RNF43 is another frequently mutated gene with corresponding loss of heterozygosity found in MPCNs.

Since first reported in the literature in 1982 as “mucin-producing tumors,” intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs) have continued to garner widespread attention.34 In the last three decades, the number of patients diagnosed with IPMN has dramatically increased, and our knowledge of their growth patterns and pathologic differences has evolved.

Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms account for up to one-third of all PCNs detected and are defined as grossly visible (≥1 cm) mucin-producing pancreatic cysts that arise from the main pancreatic duct (MPD) and its branches.35 IPMNs occur in individuals 60 to 70 years of age, with a mean age of 63 to 66 years at diagnosis.36 Unlike MCNs, IPMNs are found in both genders and are found slightly more often in men. Up to 70% of IPMNs are localized to the head of the pancreas and are more likely to be symptomatic when compared to MCNs.37 Common presenting symptoms include abdominal pain, recurrent pancreatitis, weight loss, nausea, and vomiting.38 Symptoms of pancreatic insufficiency, including steatorrhea and diabetes mellitus, and jaundice may be observed.37,39,40 However, the presence of these later findings are often associated with more advanced lesions. Increased incidence of IPMNs have also been reported in patients with Peutz–Jeghers syndrome and patients with familial adenomatous polyposis.41,42

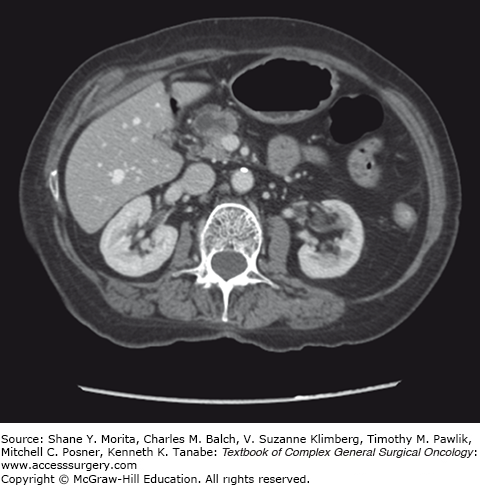

There are three clinical subtypes of IPMN seen radiographically and histologically, including main-duct IPMN (MD-IPMN), branch-duct IPMN (BD-IPMN), and mixed type. MD-IPMN is defined as diffuse or segmental dilatation of the main pancreatic duct >5 mm without associated masses, accounting for roughly 20% to 36% of IPMNs.13,36,43 Two-thirds of all MD-IPMNs are found within the head of the pancreas, and on CT imaging, prominent dilatation of the main pancreatic duct is seen (Fig. 148-3). Lesions may be localized, multicentric, or diffusely distributed throughout the gland, as seen in approximately 8% of cases.43,44 MD-IPMN is the most aggressive clinical subtype, 60% of which demonstrate high-grade dysplasia, and 45% associated with invasive carcinoma.37,40,43 Any suggestion of solid components, mural nodules, or associated masses on imaging must be treated with a high suspicion of underlying malignancy.45

Mixed-type IPMNs involve both the main pancreatic duct and its side branches, and represent about one-third of all IPMNs. Because of the involvement of the main pancreatic duct, this subtype has a similar presentation and behavior as MD-IPMN, including a high malignant profile.46 Although their distinction may have important consequences regarding underlying malignancy and surveillance, mixed-type IPMN is ultimately managed in the same manner as MD-IPMN.

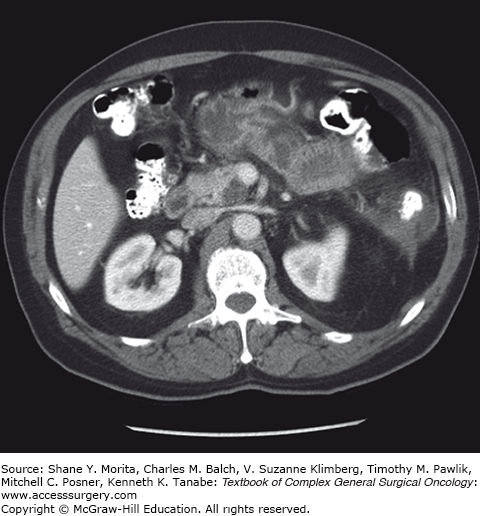

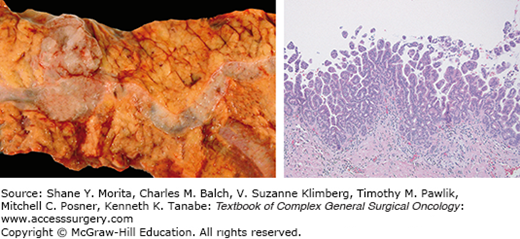

Branch-duct IPMNs account for approximately 38% to 48% of all IPMNs diagnosed and are often incidentally found.36,43 These lesions are typically asymptomatic and have a more indolent course when compared to MD-IPMN.47 CT scan findings demonstrate cystic dilatation of small branches of the pancreatic ductal system, and multifocality (more than two lesions) is seen in approximately 30% to 40% of cases12 (Fig. 148-4). Furthermore, BD-IPMNs are frequently seen as a cluster of small cysts, resembling a growth pattern like a “bunch of grapes,” most often within the pancreatic head or uncinate process.48 Although BD-IPMN carries less malignant potential when compared to MD-IPMN, it should still be approached as a premalignant lesion. In patients with resected BD-IPMN, high-grade dysplasia was reported in 25% of cases, and invasive carcinoma was observed in 20%.49 A recent study suggested that the location of the BD-IPMN might also have clinical importance, with uncinate lesions having higher incidence of harboring malignancy at smaller sizes.50

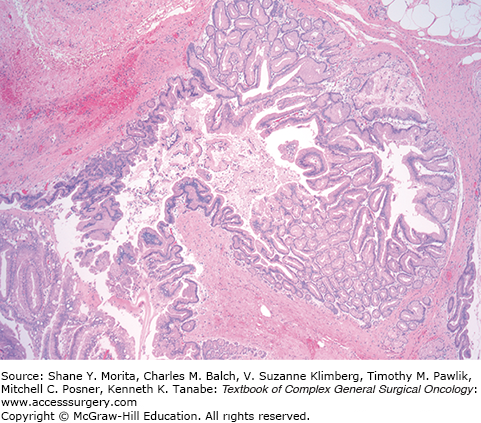

Grossly, the pancreatic parenchyma surrounding MD-IPMNs is frequently firm and pale from the scarring secondary to chronic obstruction (Fig. 148-5), but is largely absent in BD-IPMNs8 (Fig. 148-6). Microscopically, IPMNs are characterized by intraductal proliferation of neoplastic mucinous cells that form papillae, leading to cystic duct dilatation and formation of clinically and macroscopically detectable masses (Figs. 148-6 and 148-7).51–53 This is in direct contrast to PanIN lesions, which are microscopically detected, and are unassociated with mass formation.35,54

Like MCNs, IPMNs display a range of cellular atypia, and similarly, a shift in nomenclature occurred as our understanding of these lesions increased.8,13,55 Noninvasive IPMNs with a single layer of well-oriented neoplastic cells, with no evidence of mitosis or necrosis, can be classified as low-grade dysplasia (formerly adenoma). IPMNs with moderate dysplasia (formerly borderline tumors) show some nuclear atypia and nuclear pleomorphism.46 IPMNs with high-grade dysplasia (known as carcinoma, noninvasive or invasive) demonstrate complex cellular atypia with cribriforming, loss of polarity, and nuclear polymorphism.8 As described for MCNs, IPMNs should be categorized based on the highest grade of dysplasia.

There are five distinct histological patterns found in the papillae of IPMNs, including gastric-foveolar type, intestinal type, pancreatobiliary type, intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasm, and intraductal oncocytic papillary neoplasm (IOPN). Cells in the gastric-foveolar type are often low-grade lesions found in BD-IPMN, but there are some instances in which high-grade dysplasia have been reported.46,56 This phenotype has been referred to as the null type, because it is also found in the nonpapillary regions of MD-IPMN.8 Intestinal-type IPMNs are histologically similar to villous adenomas of the colon and are associated with intermediate and high-grade dysplasia typically seen in MD-IPMN. When associated with invasive disease, most intestinal-type IPMNs tend to be colloid carcinoma.57,58

Pancreatobiliary-type IPMNs form more complex papillae and are higher-grade, more aggressive lesions. Invasive cancer associated with this type is frequently found to be tubular carcinoma, with morphologic features of ductal adenocarcinoma.57

Recently, intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasms were introduced as a new entity. This IPMN type is associated with uniformly dilated pancreatic ducts, with high-grade dysplasia observed uniformly throughout the tumor. Furthermore, it can be distinguished from other types by its more solid growth and scant mucin, necrotic foci, and absence of KRAS2 gene mutation seen in the majority of all IPMNs.59

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree