Morphologic Classification of Colorectal Epithelial Tumors

Rhonda K. Yantiss

Malignant colorectal epithelial neoplasms are broadly classified as carcinomas and (neuro)endocrine tumors. Invasive colorectal carcinomas are defined by infiltration through the muscularis mucosae into the submucosa and/or deeper soft tissues. More than 90% are gland-forming adenocarcinomas with an intestinal phenotype, although several other histopathologic subtypes exist (Table 7.1). These variants are important to recognize because some are associated with specific molecular characteristics, such as microsatellite instability (MSI-H), whereas others are defined as high-grade neoplasms at risk for biologically aggressive behavior. (Neuro)endocrine neoplasms are classified as well-differentiated and poorly differentiated tumors and included in the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, seventh edition.1 The purpose of this chapter is to discuss the types of malignant colorectal epithelial tumors, their clinical features, morphologic characteristics, and molecular associations.

COLORECTAL CARCINOMA

Clinical Features

Colorectal carcinoma is largely a disease of older adults and is slightly more common among men than women. Higher rates are observed in industrialized countries of Europe and North America, as well as Australia and New Zealand, relative to less well-developed countries. Cancer rates increase among immigrants and their descendants from low-incidence regions to match those of their adoptive countries. Obesity, meat consumption, smoking, and alcohol are all considered modifiable colorectal cancer risk factors, whereas decreased risk is associated with increased fiber intake; diets rich in fruits, vegetables, and grains; and chronic nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use. The epidemiologic features of colorectal carcinoma are further discussed in Chapter 2.

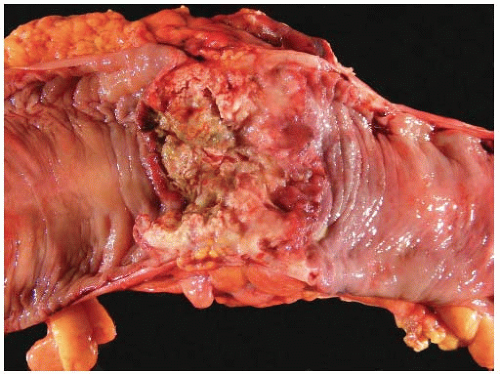

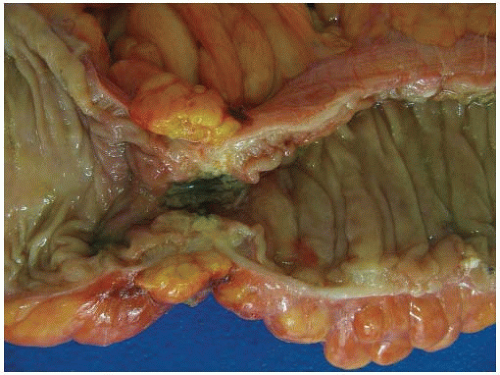

Most carcinomas are located in the distal colorectum, although cancers of the proximal colon become more common with advancing age. Many tumors are asymptomatic, early stage lesions that are detected during screening or surveillance colonoscopy. Proximal colonic cancers rarely cause obstructive symptoms because the right colon is quite distensible and contains mostly liquid stool. Tumors of the abdominal colon tend to be quite large and bleed intermittently, producing positive fecal occult blood tests and iron deficiency anemia (Figure 7.1). Carcinomas of the distal colorectum are more likely to cause changing bowel habits. Annular tumors partially obstruct the lumen, resulting in narrow caliber stools and sensations of incomplete evacuation, constipation, bloating, and distention (Figure 7.2). Some patients with obstructing cancers have diarrheal symptoms due to leakage of liquid stool around impacted solid feces. Bleeding distal tumors also cause hematochezia, especially when they develop in the rectum.

Intestinal-Type Adenocarcinoma

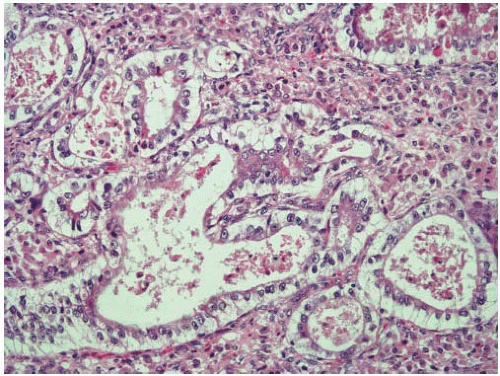

More than 90% of colorectal adenocarcinomas are composed of glands with an intestinal phenotype. Malignant glands harbor columnar epithelial cells, some of which contain cytoplasmic mucin vacuoles. The tumor cell nuclei are round or ovoid with irregular membranes, heterogeneous

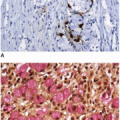

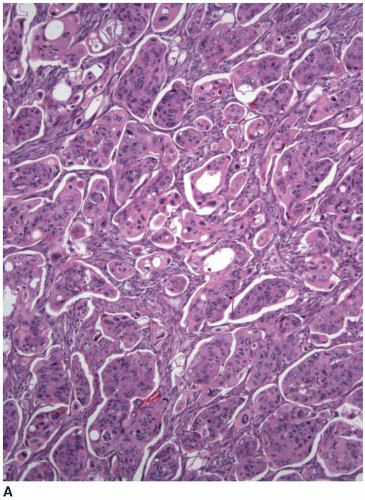

chromatin, prominent nucleoli, and numerous mitotic figures. Single cell and luminal necrosis are often prominent (Figure 7.3). Some tumors contain cells with abundant clear cytoplasm and subnuclear vacuoles that simulate the appearance of secretory endometrium or other mülleriantype malignancies, particularly when they present in extraintestinal sites (Figure 7.4). Welldifferentiated tumors may show a predominantly villous architecture that closely simulates the appearance of an adenoma. Intestinal-type adenocarcinomas of the colorectum show a characteristic immunophenotype. They are negative for cytokeratin 7 and display positivity for cytokeratin 20, CDX-2, and CDH17.2

chromatin, prominent nucleoli, and numerous mitotic figures. Single cell and luminal necrosis are often prominent (Figure 7.3). Some tumors contain cells with abundant clear cytoplasm and subnuclear vacuoles that simulate the appearance of secretory endometrium or other mülleriantype malignancies, particularly when they present in extraintestinal sites (Figure 7.4). Welldifferentiated tumors may show a predominantly villous architecture that closely simulates the appearance of an adenoma. Intestinal-type adenocarcinomas of the colorectum show a characteristic immunophenotype. They are negative for cytokeratin 7 and display positivity for cytokeratin 20, CDX-2, and CDH17.2

Table 7.1 Morphologic Variants of Epithelial Cell Neoplasms of the Colorectum | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Micropapillary Carcinoma

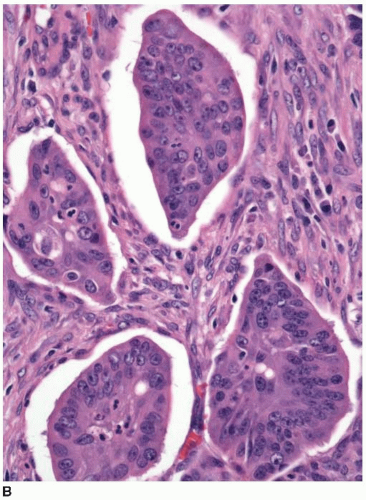

Approximately 10% of colorectal carcinomas contain a micropapillary component, but fewer than 1% of tumors are classified as micropapillary carcinomas. This tumor type is more aggressive than conventional adenocarcinoma, and the presence of a micropapillary component is an adverse prognostic factor among stage I and stage II colorectal carcinomas.3,4 More than half of cases are locally advanced with lymphovascular invasion and multiple (>4) regional lymph node metastases.4,5 Micropapillary tumors contain solid cell clusters within lacunar spaces that simulate vascular invasion (Figure 7.5). They show peripheral staining for MUC1, a glycoprotein necessary for maintenance of cell lumina, which may inhibit tumor cell/stromal interactions and contribute to the morphologic appearance of this tumor type.6 Micropapillary carcinomas show cytokeratin 20 positivity and negativity for cytokeratin 7 and are usually microsatellite stable (MSS).

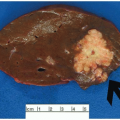

FIGURE 7.1: This transverse colectomy specimen contains a large fungating adenocarcinoma with necrosis and hemorrhage. The tumor was discovered during evaluation for microcytic anemia. |

FIGURE 7.2: An annular adenocarcinoma of the sigmoid colon produces an area of luminal narrowing. The proximal end of the specimen shows mild dilation (left). |

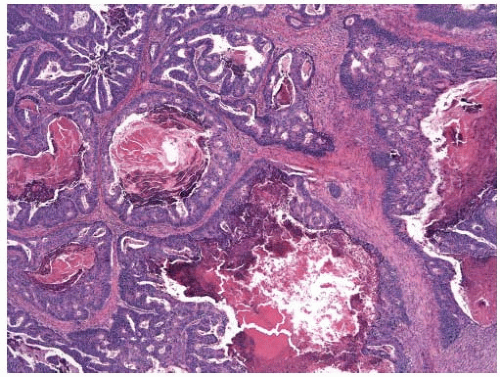

Cribriform-Comedo-Type Adenocarcinoma

Cribriform-comedo-type adenocarcinoma is recognized by the WHO as a colorectal cancer subtype with morphologic features reminiscent of ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast.7 Tumors with this morphology account for less than 1% of all colorectal carcinomas and tend to occur in the proximal colon of older adults.8 Cribriform-comedo-type adenocarcinomas are composed of expansile sheets of malignant glands with a fused growth pattern. Luminal necrotic material is prominent (Figure 7.6). The tumor cells show high-grade cytologic features with enlarged nuclei and prominent nucleoli. Cribriform-comedo-type carcinomas are usually MSS, but show CpG island hypermethylation.8

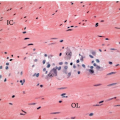

FIGURE 7.5: Micropapillary carcinoma contains sheets of tumor cells without apparent gland formation (A). |

Serrated Adenocarcinoma

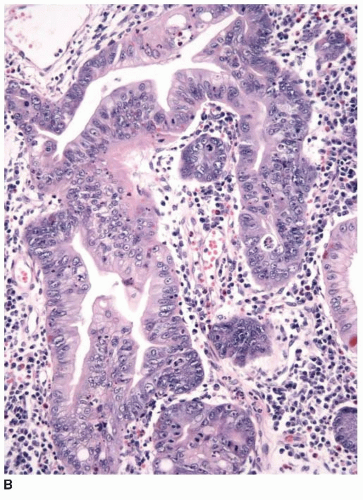

Serrated adenocarcinomas typically arise in the abdominal colon and are more common among older female adults.7 They represent one putative endpoint of the serrated neoplastic pathway, as discussed in Chapter 4, although most colonic carcinomas derived from serrated polyps do not have a serrated

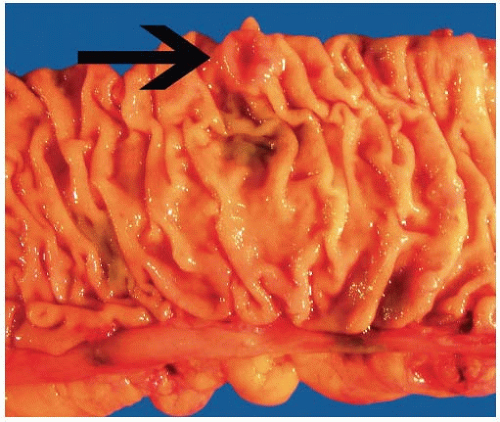

appearance. In fact, serrated polyps may be seen in combination with 17% of proximal colonic carcinomas, but less than 20% of these tumors have morphologic features that warrant classification as serrated adenocarcinoma.9 Serrated adenocarcinomas are often small, plaque-like nodules that may be associated with sessile polyps (Figure 7.7). They contain neoplastic glands with a serrated architecture and abundant, often eosinophilic, cytoplasm; large nuclei; and prominent nucleoli (Figure 7.8).

appearance. In fact, serrated polyps may be seen in combination with 17% of proximal colonic carcinomas, but less than 20% of these tumors have morphologic features that warrant classification as serrated adenocarcinoma.9 Serrated adenocarcinomas are often small, plaque-like nodules that may be associated with sessile polyps (Figure 7.7). They contain neoplastic glands with a serrated architecture and abundant, often eosinophilic, cytoplasm; large nuclei; and prominent nucleoli (Figure 7.8).

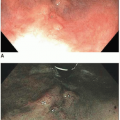

FIGURE 7.7: A serrated adenocarcinoma forms a small plaque-like nodule with central umbilication (arrow). |

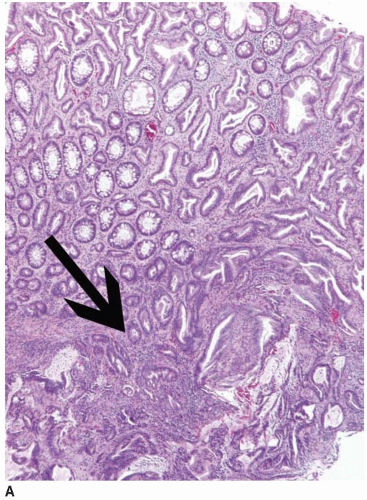

FIGURE 7.8: An early invasive serrated adenocarcinoma is associated with a serrated polyp in the mucosa (A). |

These tumors frequently contain other elements, including cribriform glands, mucin pools, and signet ring cells. The molecular features of serrated adenocarcinoma are variable. Fewer than 20% of tumors show molecular features typical of the serrated neoplastic pathway, namely, BRAF mutations, CpG island hypermethylation, and MSI-H. They may be MSS, harbor KRAS mutations, or display relatively little DNA hypermethylation.9

COLORECTAL CARCINOMAS WITH SPECIFIC CLINICOPATHOLOGIC CHARACTERISTICS

Mucinous Adenocarcinoma

Up to 10% of all colorectal adenocarcinomas are classified as mucinous carcinomas, as defined by the presence of extracellular mucin pools comprising more than 50% of the tumor volume. Carcinomas that show less than 50% mucinous differentiation are classified as adenocarcinomas with a mucinous component. Mucinous adenocarcinomas occur in two specific situations. They are the most common adenocarcinomas to complicate chronic anal sinuses and fistulae in patients with, or without, Crohn disease.10 In addition, 20% to 60% of mucinous adenocarcinomas show underlying MSI-H, and thus, their clinical features and biologic behavior mirror those of sporadic MSI-H cancers in older adults and heritable tumors affecting patients with Lynch syndrome.11,12 Mucinous tumors with MSI-H are associated with a better prognosis than MSS mucinous adenocarcinomas.13

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree