Introduction

The concept of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) as an intermediate state between normal cognition and dementia entered into the vernacular of geriatric medicine in the past 15–30 years. What this chapter may add to our understanding is that it is a relatively precise clinical diagnosis and a useful research tool. More often than not, the clinical diagnosis of MCI may have be applied to patients who are either normal or who have dementia. Although this misclassification may be a disservice to the diagnosis of MCI, the bigger disservice is to the patient. Geriatricians need to use the diagnosis appropriately for patient care, understand the treatment limitations, apply appropriate management strategies and embrace the research opportunities presented by this construct.

History

Mild cognitive impairment as a term was introduced into the literature in 1988 by Reisberg et al.,1 but referred to a severity index of stage 3 as identified on the Global Deterioration Scale. Another instrument, the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale, sought to identify very early dementia given the possibility of identifying disease early and intervening as soon as possible.2 By 1999, MCI had been proposed as a prodromal condition for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) with the focus on memory as a chief clinical complaint for incipient disease.3

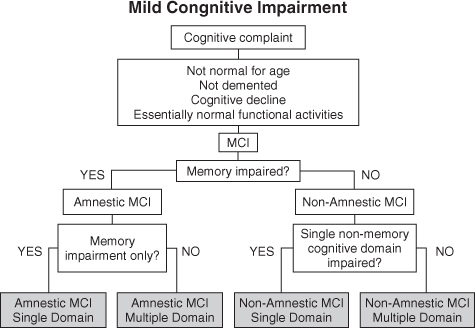

It was evident by the turn of the decade that not all forms of MCI evolved into AD. However, the general construct served most clinicians well enough. The difficulty was then, and still is today, that all too often MCI is used to soften a diagnosis of what should really be dementia. In 2004, Winblad et al.4 sought to expand and revise the criteria.5 From the symposium concerned, the criteria now used by the National Institute on Aging-Sponsored Alzheimer Disease Centers Program Uniform Data Set and the Alzheimer Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI)6 have helped us design protocols to improve our understanding of the dementing process. The clinical phenotypes now include amnestic MCI (aMCI) and non-amnestic MCI (naMCI) with the subtypes of single- and multiple-domain classifications (Figure 74.1).

While specific changes in cognition are frequently observed in normal ageing, there is increasing evidence that some forms of cognitive impairment are recognizable as an early manifestation of dementia.3 MCI is a heterogeneous state and there remains controversy over aspects of the construct. However, the utility of this paradigm is the recognition that dementia is not a dichotomous state and therefore refining our understanding of the layers of transition will improve the understanding of cognitive decline and ultimately benefit patients. Appropriate diagnosis lets us address our patients’ needs with the best available therapies, be they drug or non-drug interventions.

In general, our shortcomings in approaching patients with cognitive decline have been to avoid a diagnosis and delay our interventions. The reasons are multiple, although taking the time to make a diagnosis means that much more time will be needed to explain the diagnosis and take action. Any assault on our independence with special concern regarding the loss of driving privileges plays poorly to the American mindset. We live in a land where our first right of passage is our driver’s license and where all roads lead to the shopping mall. We do not live in walking communities and the last thing we give up is our driver’s license. There have also been financial disincentives in the past when clinicians used a psychiatric code to define cognitive disease although MCI and the dementing syndromes can b now e classified with ICD-9 medical codes.

Although no symptomatic or disease-modifying drug therapies are available for MCI, there is much that can be done. The domains of cognition, function and behaviour define this population and where they reside in the spectrum of disease. Their preserved abilities can also serve as markers for how the disease is progressing and how well they are living within a defined environment. Even without a drug treatment of MCI, understanding the environment that surrounds every one of these patients and how they function within their universe is most important. Overlearned behaviours and an environment that limit or prohibit excess disabilities should be stressed even for patients with MCI. Much can be done and running towards a diagnosis is better than running away from it.

Cognitive impairment, be it MCI or dementia, can still be defined by the capacities that are preserved and the capacities that are lost. This is where the issue of driving comes into play, but the concept applies to all kinds of tasks and opportunities. We counsel that a diagnosis is not an all-or-nothing phenomenon and many individuals with MCI or even early dementia sit on advisory boards to provide a patient voice in understanding better the needs of the patient. Unfortunately, explaining these concepts and what is both retained and what is lost takes time, especially for the primary care provider.

As our understanding of disease advances, the triad of cognition, function and behaviour not only defines the type of care that may be appropriate but also contributes to our understanding of where the best site of care might be. Our ability to address the environment early in the care of patients with MCI or other age-dependent deficiencies may improve the quality of life for our parents, avoid common pitfalls and provide for more cost-effective and successful management of the being, not just the disease they may have. A goal set by the Alzheimer’s Association back in 1987 was to create an environment where a person can function with minimal failure and maximal use of retained abilities. There is even more opportunity today to create this success with earlier diagnosis and earlier intervention.

Our earliest work in the Mayo Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center taught us that even normal individuals change as they get older. Not only does reaction time slow but on measures of Verbal IQ and measures of Performance IQ, the things we do day in and day out are better preserved.7–9 In all of our attempts at providing care to the elderly, these are the principles that shaped us early and continue to play out in the advice we give out every day. Overlearned behaviours, repetitive tasks and rehearsed activities make it easy and comfortable for us to go about the routines of the day. The things we are confronted with that take an element of problem solving become all the more difficult as we age.

In addition, the concept of MCI plays extremely well as we design hypothesis-driven research; be it with regard to clinical markers, psychological assessment, neuroimaging, biomarkers or drug and non-drug interventions.10 This is perhaps equally important as the clinical diagnosis and has generated research opportunities worldwide. The construct of MCI has been incorporated into research on ageing from multiple perspectives, including clinical research, epidemiology, neuroimaging, mechanisms of disease, clinical trials and caregiving.10

Definitions and Terminology

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) refers to cognitive impairment that does not meet the criteria for dementia. Various researchers have proposed several criteria for and subtypes of MCI.3, 11, 12 These criteria and subtypes differ somewhat, although there is considerable overlap. The Mayo criteria are the ones most commonly applied in the literature:13

- memory complaint, preferably corroborated by an informant

- memory impairment documented according to appropriate reference values

- essentially normal performance in non-memory cognitive domains

- generally preserved activities of daily living

- not demented.

It is important to emphasize that these remain clinical criteria. Considerable judgment is involved in making the distinction between impairments that are normal for the elderly population and, at the other extreme, that do not represent dementia. However, it should be noted that this is the manner in which we apply criteria for dementia and AD also. Each follows a construct, has a literature base and serves the patient best when appropriately applied.

MCI is heterogeneous in terms of clinical presentation, aetiology, prognosis and prevalence.12, 14, 15 In recognition of the narrower scope of the original Mayo criteria and others that relied heavily on memory problems, the concept was expanded. The intention of this was to broaden the scope and extend the emphasis of detection of other dementias in their prodromal stages.5, 13, 16 A useful classification criteria separates MCI into amnestic and non-amnestic groups and further into single and multiple domains. The amnestic type of MCI is generally thought to represent prodromal AD.17 Other subclasses may have different underlying mechanisms of cognitive impairment and may be associated with other non-AD disease processes [e.g. vascular dementia, frontotemporal dementia (FTD) or dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB)], but there is limited pathological evidence for this paradigm.18

The term MCI, without qualification, was traditionally and is still often used to refer to the amnestic type; however, using MCI without qualification is not the current state of affairs. This chapter includes the current breakdown into the various subtypes.

Single-Domain Amnestic MCI

Single-domain amnestic MCI (aMCI) refers to those individuals with significantly impaired memory who do not meet criteria for dementia. The criteria outlined above were initially developed to define MCI in general, but subsequently have been understood to identify only this type.3, 13

Memory impairments that qualify for MCI are generally represented by defects that are 1.0–1.5 standard deviations (SDs) or more below age-corrected norms. Although this seems straightforward, different tests of memory likely have different sensitivity and specificity and norms are not available for all populations.14

Multiple-Domain Amnestic MCI

Many individuals with aMCI complain only of memory loss; however, they may have additional subtle impairments in other cognitive domains, for example, executive function, that are revealed with careful neuropsychological testing.16, 19–21 Some would interpret the latter finding as excluding patients from this subtype of MCI according to the criteria listed above.14 This highlights the operational difficulties with the application of the criteria and was a primary reason for expanding the diagnostic categories to include single- and multiple-domain impairment.5 Such persons may manifest subtle problems with activities of daily living, but they do not meet criteria for a formal diagnosis of dementia.15 The multiple domains are, by definition, only slightly impaired (i.e. less than 0.5–1 SD below age- and education-matched normal subjects).

aMCI is often thought of as a precursor to AD.17 Although memory performances are often similar in patients with aMCI and AD, the addition of impairments in multiple cognitive domains are also prominent in patients with AD.3 Suffice it to say, the greater the extent of additional non-memory domains the smaller the distinction between MCI and AD becomes and the greater is the risk of conversion to dementia.

Often these individuals progress to meet criteria for AD or vascular dementia; in a minority of cases, the cognitive profile may simply reflect normal ageing.15 The prognostic utility of the multiple-domain form of MCI remains unclear as some studies have identified this as the highest risk category for conversion to dementia whereas others have exposed instability, with some individuals returning to baseline level of function over time.16, 22, 23 It may represent a progression of impairment from the memory domain alone to multiple domain involvement on the way to dementia.

Single-Domain Non-Amnestic MCI

The concept of single-domain non-amnestic MCI (naMCI) is similar to that for aMCI, except that this form of MCI is characterized by a relatively isolated impairment in a single non-memory domain, such as executive functioning, language or visual spatial skills.15 Depending upon the domain, individuals with this subtype of MCI may progress to other syndromes, such as FTD, including primary progressive aphasia, DLB, progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) or even corticobasalganglionic syndrome (CBS). Individuals within this group appear to be at less of a risk for conversion to dementia, although supporting evidence is limited by the operationalization of MCI diagnosis.18, 24 Uncommonly, AD may present without a memory impairment initially, so naMCI can occasionally be a prodromal state of AD.

Multiple-Domain Non-Amnestic MCI

As with aMCI, patients who meet this criterion are affected in multiple domains with a relative sparing of memory problems. The substrate of multiple-domain naMCI is felt to be that of degenerative disorders associated with tau, TAR DNA binding protein (TDP-43) and α-synuclein such as FTD and DLB.25, 26

Although these criteria were developed as an ontological concept relating early changes in specific cognitive domains to those areas most commonly affected in the disorders, that is, memory problems and AD, there remains a significant amount of crossover between groups.18 Additionally, in certain disorders, such as behavioural variant FTD, cognitive complaints are often preceded by significant alterations in behaviour and comportment. Hence some have proposed the concept of mild behavioural impairment as a similar paradigm to recognize an additional group with increased risk of dementia.27

Related Terminology

There are a multitude of loosely related terms that have been used to describe constructs that are similar to or perhaps even the same as MCI, for example, incipient dementia, isolated memory impairment, dementia prodrome, minimal AD, predementia AD, prodromal AD and early AD.3, 12, 13, 15, 28, 29 In a glossary of these and other terms that describe cognitive impairment in elderly people without dementia, most of these definitions do not fully overlap with the definition of MCI.30

The concept of MCI perhaps reflects most closely the idea of ‘cognitive impairment, no dementia’ (CIND).31 However, in contrast to the definition for the amnestic form of MCI, CIND relies less heavily on the presence of prominent memory deficits and includes in its definition the presence of a functional disability. It is a more inclusive definition than MCI and includes static encephalopathies, as is reflected by its higher prevalence.

‘Age-associated memory impairment’ (AAMI) and ‘age-associated cognitive decline’ (AACD) are also widely used and fairly well-known terms. However, these terms differ from MCI in that they were originally devised to define normal age-associated memory and cognitive changes in older adults as referenced to young normal adult individuals.3, 32, 33 AACD was developed as a way of defining better the cognitive changes in elderly compared with age-adjusted norms. AACD has more recently been recognized as identifying a state of impairment similar to MCI.34 In MCI, memory impairments are referenced to age-adjusted norms and require a decline from a previous level of functioning.

Studies of ‘preclinical AD’ should be distinguished from studies of MCI.35 In MCI studies, patients meet cognitive criteria for diagnosis and are then followed prospectively to assess for conversion to AD. As we move forward with our understanding of disease, we expect presymptomatic cases to be described and defined by biomarker data.

Some investigators challenge the inclusion of intact activities of daily living as a criterion and have suggested further refining the concept of subjective cognitive complaint.36–38 These and other judgments likely differ between assessors and account for some of the conflicting results in studies of this disorder. It is also important to note that an essential component of the diagnosis of MCI is based on the clinical history and should not rest on psychometric testing or a hesitancy to diagnose a dementia appropriately.

Case Examples

The clinical presentation of a patient with MCI typically involves a cognitive complaint. Patients or family members commonly report difficulties with ‘short-term memory’ (by which they mean recent memory) but detailed history-taking should also ask about symptoms in other cognitive domains. Motor, neuropsychiatric, autonomic and sleep symptoms also may be present and should be elicited specifically during the initial evaluation. However, the field has expanded and the differential now includes a variety of subcategories including naMCI. Two examples may help in understand the current differentiations. Potential interventions as practiced by providers who wish to intervene early are included.

70-year-Old Man with Amnestic MCI

This patient has a memory complaint and lacks other cognitive difficulties.

A 70-year-old right-handed male presents with a 2 year history of memory complaints. His wife mentions that he tends to misplace items, forget conversations and repeat himself. He maintains all activities of daily living and admits to having trouble with his memory. Although he finishes tasks with accuracy, he takes a slightly longer time to finish activities such as balancing the chequebook. He scores 34/38 on the Kokmen Short Test of Mental Status,39 losing all four points on recall. His general neurological examination is within normal limits. Formal neuropsychological testing shows impairment only in the memory domain, with difficulties in delayed verbal recall. Performance on tests of attention-executive functioning, visuospatial skills and language is in the above-average range. Screening laboratory tests did not reveal a reversible cause for his cognitive difficulties. His brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan is significant for mild bilateral hippocampal atrophy.

Discussions were undertaken early on regarding the patient’s cognitive complaints. He had preserved insight and was well aware that there was a problem. The discussion was ‘hopeful’ although his clinician was very clear that a diagnosis could already be established and that progression to a dementing syndrome still carried a strong likelihood. No drug therapy was offered and his type 2 diabetes had been well managed. An additional review of his medications revealed the use of oxybutynin for an overactive bladder and it was suggested that this drug be discontinued because of its anticholinergic burden. The family was most appreciative of this suggestion and had questioned whether the drug had provided any benefit in the first place. This discussion also provided the clinician with the opportunity to introduce the potential use of a cholinesterase inhibitor should the patient go on to manifest additional disease.

The opportunity also presented itself with regard to managing the environment of care. There had been some talk of moving to a warmer climate now that the patient was retired. They had vacationed in the previous two winters in a retirement community and enjoyed the experience. However, the patient had shown some reluctance in making a permanent move as he had misplaced the golf cart on more than one occasion. The conversation therefore turned to the most appropriate time to move and where to move. Patients with cognitive difficulties do best with stable and predictable environments. Learning becomes more difficult and the recommendation was either to move as soon as possible or not to move at all. In this way, the patient would have either the greatest opportunity to adjust to his new surroundings or benefit from the continuing, predictable and overlearned environment already surrounding him.

75-year-Old Woman with Non-Amnestic MCI

This patient’s cognitive impairment is affecting attention-executive functioning and the visuospatial domain.

A 75-year-old right-handed female presents with a 2 year history of progressive cognitive difficulties. Her daughter reports that she does not multitask or make decisions as well as she did after her husband’s death 10 years ago. She also takes longer to complete the laundry and finds it challenging to fix holiday meals. Otherwise, she maintains all activities of daily living independently and continues to drive to the grocery store. Both she and her daughter reported no problems with memory. On examination, she scores 33/38 on the Kokmen Short Test of Mental Status. Although she lost two points on learning, two points on calculation and one point on construction, she was able to state all four words on the delayed recall task. Her general neurological examination was significant for mild bradyphrenia, bradykinesia and hypomimia. Formal neurological testing showed impairment in attention-executive functioning and visuospatial skills, with above-average performance on measurements that tested the memory and language domains. Screening laboratory tests did not reveal a reversible cause for her cognitive difficulties. Her brain MRI scan also was unremarkable, without any evidence of cerebral or hippocampal atrophy.

The patient’s daughter lives out-of-state and no close relatives or friends could be counted on for support. Power of attorney for healthcare had been established shortly after the husband’s death and this was an opportunity to discuss additional advance directives. The patient had no plans for a living will but had talked extensively with the daughter about her husband’s death. She did not want to go on a ventilator as he did after his heart attack and lived like a ‘vegetable’ after his subsequent stroke. They were both in agreement that it would be best if she moved closer to her daughter and with the clinician’s support it was recommended that they do this sooner rather than later.

The daughter sought out local support and was a close friend of a social worker who worked at the neighbourhood hospital. As the mother was moving to a bigger city, there were many opportunities (none of which included living with the daughter). Both mother and daughter looked at a number of options together and, with advice provided by the social worker, chose a large campus that was essentially a continuing care retirement community. The rationale was that the mother would be able to live quite independently, although she planned to give up driving. Should her condition deteriorate, the campus had graduated programmes to attend to her needs. However, the entire campus maintained a unified philosophy, was easy to navigate and seemed to understand that patients should be left to function on their own whenever they had preserved abilities to do so. It was unlikely that the patient would ever leave the campus as a large, skilled nursing care facility was also part of the package.

Why Does it Matter?

If we wait for functional decline to define dementia, it may be too late to treat the underlying disease process.40 Moreover, since functional decline is in the definition of dementia, it is best to work with a construct that would allow intervention sooner rather than later. With this theoretical framework, many studies have been conducted to investigate the utility and prognostic outcome of the diagnoses.40

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree