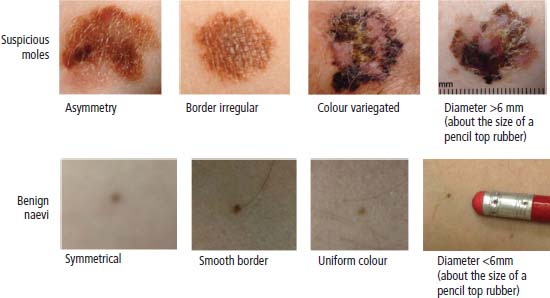

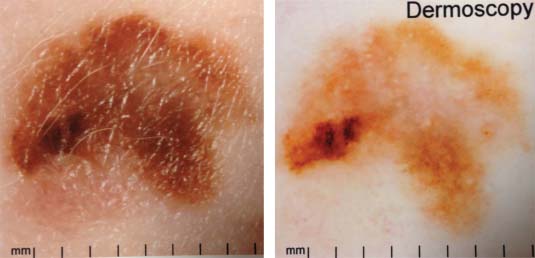

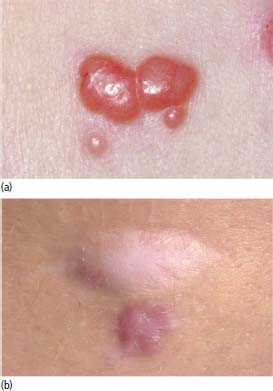

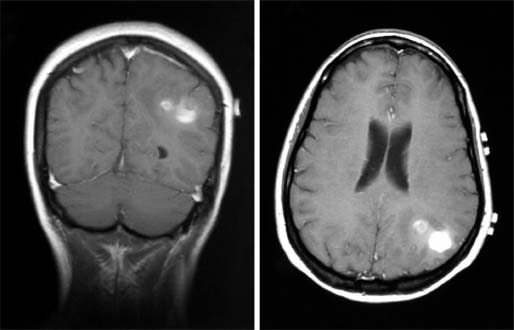

33 Melanoma is a tumour of melanocytes, the pigmented cells of the skin. The incidence of melanoma has increased by a factor of 4 since 1971. In 2011, in the United Kingdom 13,348 people were diagnosed with melanoma and 2209 died of it. The primary cause is thought to be an increase in exposure to sunlight. One hopes that with all the publicity, the risks of exposure to sun are at last entering into the public consciousness. The general public’s view of melanoma is that it has a poor outlook based on the outcomes in metastatic disease. However, as can be seen from Table 33.1, the overall outcome is generally better than for most tumour groups. Melanocytes produce two types of melanin: They are present in different proportions in people with different skin colours and at different parts of the body. This is under the influence of various pigment genes. Melanocortin 1 receptor (MC1R) is the main gene that determines whether pheomelanin or eumelanin is produced. MC1R appears to have undergone mutation and strong selection in archaic hominids in Africa about 1.2 million years ago when body hair became sparser and skin colour darker compared to chimpanzees. In populations living in regions with lower UV exposure, the benefits of reduced UV-induced DNA damage in the skin is offset by the reduced UV-induced hydroxylation of vitamin D, resulting in vitamin D deficiency. Polymorphisms of MC1R and a number of other pigment-related genes lead to paler skin hues and hence greater susceptibility to melanoma. In the United Kingdom, 80% of gingers have MC1R mutations. The risk of melanoma is dominated by a combination of skin pigment content which relates to skin, eye and hair colour (see Table 32.1) and UV exposure from the sun or sunbeds, with protection by sunscreen and enhancement by sunburn. Another risk for the development of melanoma is the presence of dysplastic or atypical moles. Most skin moles are genetically determined and appear during childhood, although sun exposure may increase their numbers. Large, unusually shaped, variegated moles with poorly defined edges are designated atypical naevi and have a 4–10 times increased risk of melanoma. This risk is even greater in people with familial atypical multiple mole–melanoma syndrome (FAMMM), although less than 5% of all melanoma cases are familial. They inherit mutations in one of two genes: cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor gene CDKN2 (also known as p16) on chromosome 9p21 and cyclin-dependent kinase gene CDK4 on chromosome 12q13. Both are implicated in insensitivity to cell cycle checkpoints. Table 33.1 UK registrations for melanoma cancer 2010 Public awareness campaigns to encourage people with suspicious skin lesions to seek advice have been based on a simple mnemonic (ABCDE) (Figure 33.1): Patients with malignant melanoma generally present with a history of a growing mole, which may bleed or itch (see Figures 33.2 and 33.3). Because of the public awareness of melanoma, generally there is quite rapid self-referral to GPs with these symptoms. Specialist referral to plastic surgery or dermatology is also quick, and many hospitals now offer walk-in skin lesion clinics. In clinic, the specialist will seek to confirm the diagnosis on initial examination (Figure 33.4). If there is no evidence for metastases, he will make arrangements to excise the primary lesion. This procedure requires specialist surgery with wide excision of the surrounding normal tissue. The reasons for this are, firstly, concerns about the incidence of local recurrence following inadequate resection and, secondly, the need for good cosmesis. Although wide excision is common, no evidence from a randomized trial supports this practice. There are four main clinical descriptions of melanoma and these are the superficial spreading, nodular, lentigo maligna and acral lentiginous subtypes (Table 33.2). Figure 33.1 Suspicious moles and benign naevi. Figure 33.2 Atypical or dysplastic naevi are large naevi (moles) with irregular borders and varied pigmentation. Atypical naevi are the precursors of melanomas. Following excision and confirmation of the diagnosis histologically, staging investigations, which should include CT scanning, should be performed. As a result of surgery and staging procedures, the clinical stage can be defined as follows: Figure 33.3 A pigmented nodular lesion with an irregular edge and adjacent satellite lesions. This was a nodular melanoma. There are additional widely practised staging systems which are not included in this book. For prognostic purposes, however, pathological staging is significant and includes the Breslow thickness and Clark’s levels: Breslow’s staging system measures the vertical thickness of the primary tumour, grouping melanomas into “Breslow’s thickness”, as <0.75 mm, 0.76–1.5 mm, 1.51–3.99 mm and >4 mm. Breslow thickness is more relevant to prognosis than Clark’s level. Figure 33.4 Dermatoscopy (also known as dermoscopy or epiluminescence microscopy). Dermoscopy combines a magnifying glass and polarized light to cancel out skin surface reflections. It increases the accuracy of melanoma clinical diagnosis by dermatologists about 20%. Table 33.2 Clinicopathological features of four common forms of melanoma Most patients who have had a definitive resection of melanoma do well, but a subset of tumours recur. Many clinical trials have addressed the role of adjuvant immunotherapy to reduce the risk of recurrence. For patients with higher recurrence risks based on tumour size, the presence of ulceration or lymph node involvement and the mitotic rate of the tumour, adjuvant interferon prolongs progression-free survival. This approach should be reserved for patients with a good performance status and no co-morbidities as interferon alpha is associated with frequent and serious toxicities including: Locoregional metastasis in melanoma includes local recurrence, satellite, in-transit and regional lymph node metastases. Satellite metastases are skin or subcutaneous lesions within 2 cm of the primary and are thought to represent intralymphatic extensions of the primary tumour (Figure 33.5). In-transit metastases arise in lymphatics more distant from the primary site but still before reaching the regional lymph nodes (Figures 33.6 and 33.7). Figure 33.5 (a) Satellite metastases are skin or subcutaneous lesions within 2 cm of the primary and are thought to represent intralymphatic extensions of the primary tumour. (b) In-transit metastases arise in lymphatics more distant from the primary site but still before reaching the regional lymph nodes. Figure 33.6 Fungating inguinal lymph node melanoma metastasis. The treatment of these patterns of relapse is primarily surgical. Localized recurrence is excised and nodal metastases are managed by radical lymph node dissection. There are advocates of regional infusional programmes (isolated limb perfusion using cytotoxic chemotherapy such as melphalan) but the value of this is contentious. Radiotherapy may be used where localized disease is inoperable or as an adjuvant to surgery, reducing the bulk of disease prior to definitive surgery. Figure 33.7 Local cutaneous recurrence of melanoma. The outlook for patients with metastatic melanoma is poor. Patients generally have disease in multiple sites, and the median survival is approximately 6 months (Figure 33.8). Treatment depends upon the patient, on his or her fitness and on the disease site. Patients with metastatic melanoma who have only a single or very limited number of metastases may be considered for surgical metastasectomy. These have been exciting times for melanoma oncologists with the development of treatment targeting molecular changes in this condition, but cost-benefit analyses have dampened the excitement. Recent advances in the management of advanced melanoma have altered the algorithm of care and produced modest but nonetheless genuine improvements in survival. Initial systemic treatments depend upon the molecular biology of the tumour and the performance status of the patient. The options are immunotherapy with high-dose interleukin-2 (IL-2) or ipilimumab, an anti-CTLA-4 monoclonal antibody or targeted therapy chiefly with inhibitors of BRAF, a signal transduction protein kinase. Patients whose tumours have the V600 mutations of the BRAF gene are candidates for treatment with the BRAF inhibitors vemurafenib and dabrafenib. If the tumour has wild-type BRAF, treatment with ipilimumab is appropriate. Ipilimumab targets CTLA-4, which normally limits the activation of cytotoxic T-lymphocytes presented with an antigen by dendritic cells. Thus imilimumab takes off this brake and allows host immune cells to destroy melanoma cells. These new approaches have been shown to have profound effects on survival in melanoma. A similar immunotherapeutic approach to melanoma is developed based on the PD-1 (programmed cell death) protein that is expressed on the surface of dying exhausted cytotoxic T-cells. Monoclonal antibodies that block PD-1 and hence rejuvenate the T-cells have shown promise in melanoma as well as other malignancies. Currently there is interest in the potential benefits of the combination of vemurafenib and ipilimumab. However, regard must be given to the potential toxicities of this combination particularly on the liver and the NHS purse. Figure 33.8 Intracerebral metastases of melanoma. On the basis of records of 25,000 patients with localized stage I/II melanoma, two online tools are available that predicts prognosis (http://www. melanomaprognosis.org and http://www.lifemath.net) which interrogates the American SEER (Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results) database. The most important prognostic factor remains clinical stage, and the depth of tumour invasion is the most important prognostic factor for localized melanoma. This can be described according to Clark’s stage and Breslow’s thickness. Ten-year survival for a lesion less than 0.75 mm thick or for a Clark’s level I melanoma is 90%, for a lesion 0.75–1.5 mm thick or Clark’s level II is 80%, for a lesion 1.6–2.49 mm thick or Clark’s level III is 60%, for a lesion 2.5–3.99 mm thick or Clark’s level IV is 50%, and for a lesion greater than 4 mm or Clark’s level V is approximately 30%. Approximately 90% of stage I patients, 60% of stage II patients and 30% of stage III patients survive for 10 years. The survival of stage IV patients depends upon the metastatic site, survival is better if metastases are confined to the skin or lymph nodes than if there is visceral involvement. Other important survival factors have been described from multifactorial analyses. They include the type of initial surgical management, pathological stage, ulceration, presence of satellite nodules, a peripheral anatomical location and, to a much lesser extent, the patient’s gender, age and tumour diameter. The American Joint Committee on Cancer, in a study involving 60,000 patients, has provided recent information on survival. This ranges from over 90% survival at 10 years for stage I disease to, as might be expected, the usual miserable outlook of only 15% survival at 5 years for metastatic disease. Case Study: The Chelsea pensioner with a leg ulcer.

Melanoma

Epidemiology

Pathogenesis

Percentage of all cancer registrations

Rank of registration

Lifetime risk of cancer

Change in ASR (2000–2010)

5 year overall survival

Female

Male

Female

Male

Female

Male

Female

Male

Female

Male

Melanoma

4

4

6th

6th

1 in 56

1 in 55

+39%

+57%

92%

84%

Presentation

Staging and grading

Type

Location

Age (median)

Gender and race

Edge

Colour

Frequency

Superficial spreading

All body surfaces, especially legs

56 years

White females

Palpable, irregular

Brown, black, grey or pink; central or halo depigmentation

50%

Nodular

All body surfaces

49 years

White males

Palpable

Uniform bluish black

30%

Lentigo maligna

Sun exposed, areas, especially head and neck

70 years

White females

Flat, irregular

Shades of brown or black, hypopigmentation

15%

Acral lentigenous

Palms, soles and mucous membranes

61 years

Black males

Palpable, irregular nodule

Black, irregularly coloured

5%

Treatment

Adjuvant therapy

Management of local skin metastases and nodal disease

Treatment of metastatic melanoma

Prognosis

ONLINE RESOURCE

ONLINE RESOURCE

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree