Chapter 10

Mastectomy for Risk Reduction and Treatment

MASTECTOMY (surgically removing the breasts) is sometimes the wisest course of treatment. Unilateral mastectomy removes one breast; bilateral mastectomy removes both. Although aggressive and drastic, prophylactic bilateral mastectomy (PBM)—removing both healthy breasts—is the most effective way to reduce your chance of developing breast cancer.

Reducing Cancer Risk by Removing the Breasts

PBM lowers breast cancer risk by 90 percent or more.1 Regardless of its risk-reducing efficiency, removing a healthy breast to avoid breast cancer is a tough decision, and it isn’t acceptable to everyone. For some women, removing breasts to prevent cancer they may never develop seems extreme. For others, the decision remedies the concern they feel, especially if they’ve seen loved ones wage war against breast cancer. Individual circumstances and tolerance for risk greatly influence one’s decision. Two women of the same age and same risk may approach the option of mastectomy differently. One might decide to delay or forego mastectomies, while the other may feel a more urgent need to address her risk surgically. Whatever your circumstances, mastectomy is irreversible. Have a clear sense of your own risk, speak with your healthcare team, and think carefully before deciding if it’s the best risk management option for you.

Until the 1970s, a woman with breast cancer had one treatment option: the deforming and debilitating Halsted radical mastectomy that removed her entire breast, including skin and underlying pectoral muscle. Today, mastectomy is rarely that extreme, unless a woman has a tumor in the chest wall. When invasive cancer is found, a modified radical mastectomy removes the entire breast, including the nipple, areola, and some underarm lymph nodes. A total mastectomy removes breast tissue and spares the lymph nodes for high-risk women who choose preventive surgery.

After mastectomy without reconstruction

If you’re facing mastectomy, you have a lot to think about. But it’s the best time to consider whether you want to have new breasts created, because certain mastectomy procedures accommodate shorter, less-visible incisions for immediate reconstruction when both surgeries are performed during a single visit to the operating room. If you have immediate reconstruction, you enter the operating room with your own breasts, which are removed and then rebuilt while you’re under anesthesia, so you wake up with new breasts in place. If you decide not to have reconstruction, as many women do, your surgeon will make two incisions from side to side across the entire breast. He’ll remove your breast tissue, nipple, areola, and most of the breast skin, and then suture the edges of the incisions together in a straight line. If you have delayed reconstruction in the future, your mastectomy scar will remain on your reconstructed breast. Doctors often don’t inform mastectomy patients, particularly older women, of their reconstructive options. That’s unfortunate, because all women deserve to be treated as individuals and make their own decisions about what’s in their best interest. It pays to do your own research.

Consider reconstruction before your mastectomy

Sampling Lymph Nodes

The lymphatic system, including lymph nodes, vessels, and fluid, is a critical part of the immune system. Lymph fluid circulates through the body, collecting bacteria, viruses, dead blood cells, and other unwanted materials, including cancer cells. Lymph nodes filter out these pathogens, returning cleansed lymph to the circulatory system. You’ve probably noticed the glands in your neck (they’re really lymph nodes) swell when you get strep throat. That’s because white blood cells within the nodes are trying to clear away infection-causing cells.

Whenever invasive breast cancer is diagnosed, lymph nodes in the axilla (underarm) are sampled to see if they contain malignant cells. Any nodes that look or feel cancerous are removed during mastectomy in a procedure called axillary lymph node dissection. This is an important step in staging cancer and planning treatment, because if cancer cells are found in the lymph nodes, it indicates that more treatment may be needed. For most women diagnosed with early stage cancer, when lymph node involvement is unlikely, less invasive sentinel node biopsy is usually performed instead. By injecting a blue dye or radioactive tracer (or both) into the breast, the surgeon can follow the lymph system from the tumor to the sentinel node (usually the node nearest to the tumor). If the sentinel node contains cancer cells, an axillary dissection is then performed to determine whether other nodes are affected. If the sentinel node is free of cancer cells, the patient is spared the more invasive axillary dissection. Having negative nodes means cancer is less likely to have spread beyond the breast or to return after treatment.

Lymph nodes aren’t usually removed during PBM, because previvors are assumed to be free of breast cancer. In a small percentage of high-risk women, cancer is discovered during prophylactic mastectomy, and some surgeons perform sentinel node biopsy as a precautionary measure. If invasive breast cancer is found during PBM, some underarm lymph nodes are sampled.

Skin-Sparing Procedures

If you have mastectomy with immediate reconstruction, your breast surgeon will perform a skin-sparing procedure to remove as much breast tissue as possible while leaving most of the skin in place to hold your new breast. Typically, the nipple and areola are cut away and the breast tissue is then removed through the opening. If you have a large tumor or large breasts, your surgeon may need to make an additional vertical or horizontal incision from the nipple. Skin-sparing mastectomies aren’t recommended for women who have cancer in or very near the breast skin.

Skin-sparing incisions

Nipple-Sparing Mastectomy

Removing the nipple has traditionally been considered a mandatory part of the mastectomy procedure. Since breast cancer rarely occurs afterward, nipple-sparing mastectomies, particularly prophylactic mastectomies, are now more common. A nipple-sparing mastectomy conserves the areola, nipple, and most of the breast skin and is generally considered effective for preventive mastectomy. Some breast cancer patients may also be candidates, depending on the size and location of their tumor, although many physicians still consider nipple-sparing to be experimental. Individuals with tumors that are very large, aggressive, or close to (or within) the skin or nipples aren’t candidates for this operation. Unlike traditional mastectomy, a nipple-sparing procedure eliminates the need to create and tattoo a new nipple, and the outcome is often more satisfying than a breast with recreated nipples and tattooed areolas.

Nipple-sparing incisions can be placed in several locations on the breast. Incisions made around the areola risk more tissue loss, while incisions below the breast or along the side leave better blood flow to the nipple. The nipple and areola remain attached to the breast skin and its blood supply during the operation to increase the chance of healing and retained sensation. The breast tissue beneath the nipple is removed, and a sample is then reviewed by a pathologist before the mastectomy is completed—it’s called a frozen section because the pathologist freezes and stains the tissue with dye to examine it microscopically. If the sample contains cancerous cells, the nipple and areola are removed. Some surgeons prefer to remove the nipple and areola during surgery, and later graft them back onto the breast.

Nipple-sparing incisions

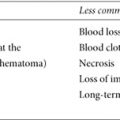

Women sometimes feel strongly about keeping their nipples, yet it often proves disappointing. Without the infrastructure of nerves and tissue, regrafted nipples may not respond to sensation or cold and often have little or no feeling. Sometimes the nipple-areola complex is poorly positioned on the new breast (particularly with large or drooping breasts) or suffers necrosis (tissue death from insufficient blood supply) and must be removed anyway. The remaining nipple may be flattened, although it can be plumped somewhat with soft tissue fillers.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree