Mastectomy

Monica Morrow

Mehra Golshan

HISTORY OF MASTECTOMY

The origin of the word mastectomy is the Greek term mastos, meaning the breast. Over the past century, the procedure has evolved considerably from the initial descriptions by Halsted and Meyer in the mid-1890s. In 1894, William Stewart Halsted published the Johns Hopkins Hospital experience with radical mastectomy, reporting a remarkable local regional control rate of 73% with no operative mortality (1). The actuarial survival rate was double that of untreated patients, with a 5-year survival rate of 40%, despite the advanced stage of many of the tumors and the lack of any adjuvant therapy. At that time, the success of the procedure was attributed to the en bloc removal of the breast and its draining lymphatics, and, after this report, the radical mastectomy remained the standard of care until the 1970s.

It eventually became apparent that the radical mastectomy failed to cure many women with breast cancer, and this was attributed by some to its failure to include all of the draining lymphatics of the breast in the en bloc resection. The extended radical mastectomy, which included the en bloc resection of the internal mammary nodes and the medial ribs, was developed to address this issue. After a randomized trial failed to demonstrate a survival benefit for this more morbid procedure (2), it was abandoned. The adoption of the modified radical mastectomy, a term used to describe a variety of surgical procedures that included removal of the entire breast and the axillary nodes but not the pectoralis major muscle, represented a major departure from the Halstedian principles of en bloc cancer surgery. Only 2 relatively small randomized trials directly compared radical and modified radical mastectomy, and neither found a survival difference. The major impetus for abandoning radical mastectomy was the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) B-04 trial. This study randomized clinical node negative women to radical mastectomy, simple mastectomy with node field irradiation, or simple mastectomy with no axillary surgery and delayed axillary dissection if clinical axillary metastases developed. After 25 years of follow-up, no survival differences have ever been apparent between treatments (3). Remarkably, in this trial done prior to the use of any adjuvant systemic therapy, although 40% of patients in the radical mastectomy group had axillary nodal metastases, only 18.5% of those randomized to the simple mastectomy and axillary observation group developed axillary first failure. This trial was a watershed in our understanding of the biology of breast cancer and paved the way for trials of breast-conserving therapy (Chapter 35), the use of immediate breast reconstruction (Chapter 36), and, ultimately, abandonment of axillary dissection in patients with a positive sentinel node undergoing breast-conservation therapy (Chapter 37).

PATIENT SELECTION AND CRITERIA FOR INOPERABILITY

Patient evaluation and relative and absolute contraindications to breast-conserving therapy necessitating mastectomy are discussed in detail in Chapter 35. Briefly, contraindications result from the inability to reduce the tumor burden to a microscopic level, where it is likely to be controlled by radiotherapy, and the inability to safely deliver radiotherapy. Thus, multicentric disease, extensive malignant-appearing microcalcifications, and inability to obtain negative margins are contraindications related to disease burden, while a history of prior irradiation to the breast region and early pregnancy are contraindications related to the inability to safely irradiate the patient. Most women with stage 1 and 2 breast cancer are candidates for breast conservation. In a population-based study of 1,984 women treated in 2005-2006, 13% were felt to have contraindications to breast conservation, and 9% attempted lumpectomy but were converted to mastectomy. Additionally, 9% of women opted to undergo mastectomy in the absence of contraindications to breast conservation (4). Mastectomy today refers to total or complete mastectomy, with axillary staging with sentinel node biopsy in the clinically node-negative patient, or needle biopsy in the patient with clinically suspicious nodes. Mastectomy with axillary dissection is termed modified radical mastectomy. There are virtually no indications for radical mastectomy as an initial management approach to breast cancer at this time. However, there are some patients whose disease is too advanced to be approached with any

type of mastectomy as initial therapy, and would be treated with drug therapy and/or radiation first.

type of mastectomy as initial therapy, and would be treated with drug therapy and/or radiation first.

Criteria for inoperability were described by Haagensen in 1943 based on outcomes of patients treated between 1915 and 1935 (5) and remain surprisingly relevant today. They include inflammatory carcinoma, satellite skin nodules, extensive edema of the skin of the breast, ulceration, and fixation of the tumor to the boney chest wall. Edema of the ipsilateral arm, fixed axillary nodes, and supraclavicular metastases are all indications of inoperable nodal disease. Inoperability is readily apparent based on a physical examination. Patients with small areas of skin ulceration due to very superficial tumors are not uniformly inoperable. Involvement of the pectoralis major by tumor is not an indication of inoperability, nor is it incorporated in the TNM staging system. In practice, there is no indication today for resection of the pectoralis major (radical mastectomy) as a primary surgical approach. Patients with large tumors involving a substantial amount of the pectoral muscle should be treated with neoadjuvant therapy, as should patients with classic signs of inoperability (see Chapter 58, Locally Advanced Breast Cancer). In contrast, patients with T1 and T2 tumors located posteriorly in the breast do not a priori require neoadjuvant therapy because they appear to abut the pectoral muscle and may be treated with mastectomy or breast conservation. If a tumor involves the pectoral muscle at surgery, a piece of the muscle can be removed to obtain an adequate margin. Patients presenting with distant metastases and an intact primary tumor are not offered initial local therapy, but may be treated surgically if they have a limited number of metastatic sites and a good response to systemic therapy. This controversial area is discussed in detail in Chapter 68.

Current Technique

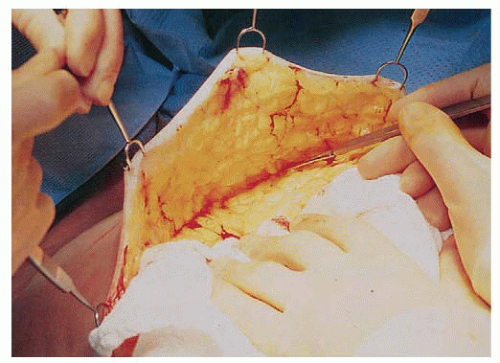

Approaches to mastectomy currently in use include total or simple mastectomy, skin-sparing total mastectomy to facilitate immediate breast reconstruction, and nipple sparing mastectomy. The approach to the axilla is independent of the type of mastectomy performed and is discussed in detail in Chapters 37 and 38. The total mastectomy procedure includes the removal of the entire mammary gland, with dissection extending superiorly to the clavicle, inferiorly to the rectus sheath insertion, medially to the sternal border, and laterally to the latissimus dorsi muscle. When axillary dissection is not performed, care must be taken to remove the entire axillary tail of the breast by extending the dissection superiorly along both the pectoralis minor and the latissimus dorsi muscles until the axillary investing fascia is entered or the sentinel node biopsy cavity is encountered. The posterior boundary of the dissection is the pectoralis major fascia. This fascia was initially thought to be an anatomic barrier to the lymphatic spread of cancer, a concept now recognized to be invalid since lymphatics penetrate the fascia, but the fascia may be preserved to facilitate expander/implant reconstruction. The flap thickness should result in removal of all of the breast parenchyma while leaving a layer of subcutaneous fat and superficial vasculature to minimize the risk of necrosis (Fig. 33-1). The flap thickness will vary with the amount of subcutaneous fat and surgical technique; however, flaps thicker than 5 mm are associated with significant residual glandular breast tissue (6).

Unfortunately, no reliable technique allows for intraoperative assessment of flap thickness. Flaps can be raised with the knife, scissor, or electrocautery, and there is no evidence of superiority of one technique. Some groups advocate the use of breast tumescence (a combination of lactated ringers and lidocaine/marcaine with epinephrine) to minimize the blood loss seen with sharp dissection. Advocates of this approach believe it minimizes thermal damage to the flap, although data on its benefits and complications are sparse (Fig. 33-2). When immediate reconstruction is not performed, the goal is to remove the breast and its excess skin so the chest wall is flat without redundant skin. A smooth chest wall surface helps to facilitate an appropriate fit for a breast prosthesis. In addition, redundant skin is difficult to care for and becomes scarred to the chest wall, so it is not useful for delayed reconstruction. Incision placement should be determined by the shape of the breast, and extending incisions medially to where they are visible in clothing is unnecessary. Transverse incisions are associated with a lower rate of skin necrosis than vertical ones. In general, the pectoralis minor muscle should be preserved. Division of its tendon facilitates access to level III lymph nodes when there is extensive axillary disease, and the muscle may be resected in the case of a bulky adherent tumor, although in the era of neoadjuvant therapy, this scenario is uncommon.

Mastectomy is an extremely safe operation that can be performed on women of all ages and on those with significant co-morbidities with a low risk of operative mortality. In a United States Department of Veterans Affairs study of 408 patients undergoing mastectomy, 73% of whom were age 50 years or older, the 30-day operative mortality rate and rate

of operation-related readmissions were both less than 1% (7). The most common complications perioperatively were superficial wound infections, seen in 6% of patients. The National Surgical Quality Improvement Program’s (NSQIP) Patient Safety in Surgery study collected data on breast surgery from 14 universities and 4 community centers. The mastectomy mortality rate was 0.24%, and the 30-day morbidity rate was 5.7% with a 3.6% incidence of wound complications (8). Factors that predispose to infection include the use of a two-step procedure (i.e., initial surgical biopsy or attempted lumpectomy) and prolonged suction catheter drainage. Early infections present as cellulitis, whereas those occurring later present as abscess. Streptococcus and staphylococcus aureus are the most common etiologic organisms. Because the incidence of infection after mastectomy is so low, the cost effectiveness of routine prophylactic antibiotic use is uncertain, although Platt et al. (9) did demonstrate that a single dose of preoperative cephalosporin reduced the incidence of infection by 38%. Antibiotics are routinely given to patients having immediate reconstruction and those who have had prior open surgery. Seroma formation is a universal occurrence after mastectomy and should not be considered a complication; drains are routinely placed to allow fusion of the dermal layer to the chest wall. Flap necrosis has become less common as abandonment of the Halstedian concepts of breast cancer surgery meant that extremely thin skin flaps and removal of large amounts of skin were no longer felt to be important to cure of breast cancer. Most flap necrosis is partial thickness and occurs adjacent to the incision line (Fig. 33-3). Skin necrosis can be minimized by avoiding removal of the subcutaneous fat layer from the flaps, closure under tension, and pressure dressings, all of which decrease the already compromised blood supply to the skin. Postoperative phantom breast syndrome is well described and occurs in approximately 25% of women after mastectomy (10). Chronic pain was previously thought to be an uncommon sequelae of mastectomy, but prospective cohort studies suggest that this syndrome is seen in 40-50% of women (11, 12). In one study, half of women who had postmastectomy pain in the early postop period had persistent pain a mean of 9 years after surgery (12). Young age is associated with a higher risk of postmastectomy pain syndrome in most studies. The pain is thought to be neuropathic in etiology, and the outcome of physical therapy and pharmacologic intervention has varied. Patients should be advised preoperatively that they will experience a loss of chest wall sensation with mastectomy, with return of a variable degree of feeling beginning about 1 year postoperatively.

of operation-related readmissions were both less than 1% (7). The most common complications perioperatively were superficial wound infections, seen in 6% of patients. The National Surgical Quality Improvement Program’s (NSQIP) Patient Safety in Surgery study collected data on breast surgery from 14 universities and 4 community centers. The mastectomy mortality rate was 0.24%, and the 30-day morbidity rate was 5.7% with a 3.6% incidence of wound complications (8). Factors that predispose to infection include the use of a two-step procedure (i.e., initial surgical biopsy or attempted lumpectomy) and prolonged suction catheter drainage. Early infections present as cellulitis, whereas those occurring later present as abscess. Streptococcus and staphylococcus aureus are the most common etiologic organisms. Because the incidence of infection after mastectomy is so low, the cost effectiveness of routine prophylactic antibiotic use is uncertain, although Platt et al. (9) did demonstrate that a single dose of preoperative cephalosporin reduced the incidence of infection by 38%. Antibiotics are routinely given to patients having immediate reconstruction and those who have had prior open surgery. Seroma formation is a universal occurrence after mastectomy and should not be considered a complication; drains are routinely placed to allow fusion of the dermal layer to the chest wall. Flap necrosis has become less common as abandonment of the Halstedian concepts of breast cancer surgery meant that extremely thin skin flaps and removal of large amounts of skin were no longer felt to be important to cure of breast cancer. Most flap necrosis is partial thickness and occurs adjacent to the incision line (Fig. 33-3). Skin necrosis can be minimized by avoiding removal of the subcutaneous fat layer from the flaps, closure under tension, and pressure dressings, all of which decrease the already compromised blood supply to the skin. Postoperative phantom breast syndrome is well described and occurs in approximately 25% of women after mastectomy (10). Chronic pain was previously thought to be an uncommon sequelae of mastectomy, but prospective cohort studies suggest that this syndrome is seen in 40-50% of women (11, 12). In one study, half of women who had postmastectomy pain in the early postop period had persistent pain a mean of 9 years after surgery (12). Young age is associated with a higher risk of postmastectomy pain syndrome in most studies. The pain is thought to be neuropathic in etiology, and the outcome of physical therapy and pharmacologic intervention has varied. Patients should be advised preoperatively that they will experience a loss of chest wall sensation with mastectomy, with return of a variable degree of feeling beginning about 1 year postoperatively.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree