of antiplatelet therapy.14 On the other hand, the risk of major bleeding episodes during the clinical course of the disease is very low (<5%).13

Table 46-1 WHO Classification of Chronic Myeloid Malignancies | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The incidence of PV is estimated to be 2.3 per 100,000 per year, and the median age at diagnosis is approximately 60 years.25 The disease affects both men and women equally but is rare in children.

Table 46-2 Causes of Thrombocytosis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

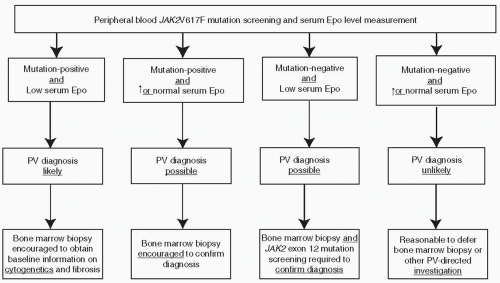

mutation screening for JAK2V617F during the initial evaluation of a patient with suspected PV (Fig. 46.2). However, at the present time, the possibility of JAK2V617F-negative PV cannot be excluded, and therefore, I encourage the concomitant measurement of serum Epo level to minimize the chances of both false negative and false positive results from mutation screening alone (Fig. 46.2). JAK2 exon 12 mutation screening is appropriate in the presence of a subnormal serum Epo level and in the absence of JAK2V617F.

Table 46-3 Risk Stratification in ET and PV | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

levels of as high as 50% might be safe.31 To date, no other or additional therapy has been shown to offer a survival advantage over treatment with phlebotomy alone. Instead, when either chlorambucil or phosphorus 32 was added to phlebotomy, survival was significantly compromised because of an increased incidence of acute leukemia. The incidence of acute leukemia over 13 to 19 years was 1.5%, 9.6%, and 13.2% for phlebotomy alone, phlebotomy and phosphorus 32, and phlebotomy and chlorambucil, respectively.30

Table 46-4 World Health Organization Diagnostic Criteria for PV, ET, and PMF | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree