I. Causes associated with surgical treatment

A. Structural change

1. Changes of soft tissue and hard tissue

Anatomic deficit, postoperative swelling, scar formation, and contracture in the lips, maxilla, palate, tongue, floor of the mouth, mandible, and oropharynx

2. Changes of muscles

Anatomic deficit, postoperative swelling, scar formation, and contracture in the facial muscles, tongue muscles, suprahyoid muscles, masticatory muscles, palatine muscles, and pharyngeal muscles

3. Reconstruction

Morphological change and reduction of movements in remained tissues

B. Impaired motor and sensory neuron

1. Damage to the trigeminal nerve

2. Damage to the facial nerve

3. Damage to the glossopharyngeal nerve

4. Damage to the vagus nerve

5. Damage to the hypoglossal nerve

C. Complications after tracheostomy (C1 and C3 are due to the tracheostomy tube; C2 is due to the tracheostomy tube with inflated cuff)

1. Restricted laryngeal movement

2. Compression of the esophagus

3. Excess tracheal secretion and pooling of the secretion

4. Reduced subglottic pressure

5. Reduced laryngeal sensitivity and delayed glottic closure reflex

II. Causes associated with radiotherapy

A. Mucositis

B. Neuropathy

C. Fibrosis

D. Xerostomia

The progress of recent surgical reconstruction techniques has made it possible to perform various grafting techniques to surgically close the deficiency after the resection; however, morphological change and reduction of movement in remaining tissues are inevitable. Recently, the neurosurgical techniques (connecting the graft and host nerves) have been attempted to acquire movement and sensation in reconstructed structures. Results of these efforts still are not sufficient to restore total function.

Surgical invasion to the peripheral nerves also results in disordered movement and sensation. Damage to the hypoglossal nerve causes reduced movements in the tongue and hyoid bone, whereas damage to the facial nerve causes the labial closure insufficiency, hypogeusia, and decreased salivation from the submandibular and sublingual glands. When the glossopharyngeal nerve and vagus nerve are damaged, velopharyngeal insufficiency and motor and sensory disorders in pharynx and larynx are observed. Also, when the motor branches of the trigeminal nerve are damaged, movements of masticatory muscles are impaired. When the sensory branch of the trigeminal nerve is damaged, sensory paralysis of oral and facial regions are observed.

In addition, tracheostomy for airway control is not rare in oral cancer surgery. Patients with tracheostomy exhibit problems such as restricted laryngeal movement caused by the tracheostomy tube, indirect compression on the esophagus by the inflated cuff, excess tracheal secretions due to the constant irritation by the tracheostomy tube, and reduced subglottic pressure due to the expiratory air leakage through the tube (Fig. 17.1). These problems result in reduced laryngeal elevation, reduced bolus passage into the esophagus, diminished laryngeal reflex, penetration (bolus entering in the larynx above the vocal folds), and aspiration (bolus entering under the vocal folds), all of which complicate the dysphagia in tracheostomized patients [3–7]. The safe and effective weaning of a patient from a tracheostomy tube should be performed to facilitate decannulation (Figs. 17.2, 17.3, and 17.4).

Fig. 17.1

Restricted laryngeal movement caused by the tracheostomy tube, indirect compression on the esophagus by the inflated cuff, excess tracheal secretions due to the constant irritation by the tracheostomy tube, and reduced subglottic pressure due to the expiratory air leakage through the tube

Fig. 17.2

The safe and effective weaning of a patient from a tracheostomy tube should be performed to facilitate decannulation. This glossectomized and mandibulectomized patient was transferred to our department from a different hospital where the patient wore tracheostomy tube with inflated cuff over 100 days after the surgery. A yellow arrow shows the tracheostomy tube with cuff

Fig. 17.3

Immediately after decannulation, the movement of vocal cord was very insufficient. The patient was encouraged to produce voicing as strongly as he can while the tracheostoma was occluded by my finger. During this procedure, suctioning from the mouth and tracheostoma was required

Fig. 17.4

The patient was encouraged to produce voicing and to expectorate secretions from the mouth as strongly as he can at the upright position, while the tracheostoma was occluded by my finger. After the safe breathing, voicing and strong huffing or coughing to expectorate secretions and sputa were verified; the retainer with peaking bulb was inserted into the tracheostoma instead of tracheostomy tube with cuff

Patients receiving radiotherapy in isolation or in combination with surgery or chemotherapy are at risk for swallowing difficulties as well. In the early stage of the therapy, pain from mucositis contributes directly to the patient’s swallowing ability. During and following the therapy, as a result of neuropathy (peripheral nerve deficit), patients often complain of a reduced sense of taste, and in some cases, a delayed pharyngeal reflex is present. Furthermore, as fibrosis of the tissue advances over time, reduced oral and/or oropharyngeal movements and/or deficits in laryngeal elevation may develop dysphagia [8, 9]. Patients also experience reduced saliva flow or xerostomia after radiotherapy. Medications (pilocarpine, cevimeline, etc.) to stimulate saliva and pseudo-saliva products (mucin-containing spray, Xanthangum-containing liquid, Sodium carboxymethylcellulose-containing liquid, Sodium chloride-containing liquid, etc.) are often only partially effective. Chemoradiation treatment results in xerostomia and a significant increase in patient perception of swallowing difficulties [10]. Xerostomia primarily affects mastication and oral manipulation of a dry, absorbent food material [11]. However, xerostomia does not affect the physiologic aspects of bolus transport or pharyngeal swallow [10, 11]. Xerostomia affects the oropharyngeal sensory process and comfort of eating more than pharyngeal swallow [10].

In summary, the swallowing disorders result from the various treatments (surgery, radiotherapy, or combination of both) for the oral cancer. Dysphagia that occurs after cancer treatments result from altered movement and coordination of structures within the swallowing mechanism.

17.1.2 Site-Specific Characteristics

1.

Labial Cancer

When the lips or marginal mandibular branch of the facial nerve is surgically affected, labial movement insufficiency is observed. Also, when the mental nerve (inferior alveolar nerve) is surgically affected, lower lip paralysis (sensation loss) is observed. In each case, problems such as drooling and the extraoral leakage of bolus are recognized as a result of labial closure insufficiency.

2.

Tongue Cancer and Oral Floor Cancer

Surgeries involving the tongue and the oral floor often result in problems with taste, bolus formulation and containment, and bolus transport from the front to the back of the mouth. Also, problems in the pharyngeal phase are often recognized because oral and pharyngeal coordination is disordered [12]. In general, patients with tongue and oral floor cancer demonstrate problems such as (1) premature leakage of bolus into the pharynx, (2) bolus control and transport difficulties, (3) residue of bolus in the oral cavity, and (4) delayed onset of pharyngeal swallow.

3.

Mandibular Gingival Cancer

Problems shown by this group of patients include (1) limited mastication due to the loss of teeth and masticatory muscles, deviation of reconstructed mandible, and sensory loss, (2) residue of bolus in the oral vestibule due to the loss of the lower alveolar ridge, alterations of shape, tension, and sensitivity in buccal tissues, (3) trismus due to the scar formation and contracture of the affected tissues, and (4) drooling and extraoral leakage of bolus due to the labial closure insufficiency or lower lip paralysis.

4.

Maxillary Gingival Cancer and Palatal Cancer (Maxillary Cancer)

The swallowing problems in patients with the resected maxilla include (1) mastication difficulty due to the loss of teeth, (2) entry of bolus into the nasal cavity due to the oronasal fistula or velopharyngeal insufficiency, (3) residue of bolus in the oral vestibule due to the loss of the upper alveolar ridge and alterations of shape in buccal tissues, (4) drooling and extraoral leakage of bolus due to the labial closure insufficiency or upper lip paralysis, and (5) trismus if the fauces or internal and external pterygoid muscles are surgically affected.

5.

Oropharyngeal Cancer

The oropharynx extends superiorly from the soft palate to the epiglottis inferiorly and anteriorly from the tongue base to the posterior pharyngeal wall posteriorly. Deficits of swallowing following oropharyngeal cancer include (1) nasal regurgitation due to velopharyngeal insufficiency, (2) bolus transport difficulty due to reduced tongue base mobility, (3) delayed onset of pharyngeal swallow due to reduced oropharyngeal sensation, (4) residue of bolus in the oral vestibule due to the alterations of shape and sensitivity in buccal tissues, and (5) trismus due to surgical invasion to the fauces or internal and external pterygoid muscles [13, 14].

17.2 Evaluation of Dysphagia

17.2.1 Noninstrumental Evaluations

1.

Medical Interview

A medical interview enables a clinician to help identify the onset, cause, site, and severity of dysphagia. From the symptoms described by the patients, a clinician is able to make assumptions of the disorders associated with swallowing such as insufficient labial closure, reduced tongue coordination for holding and transporting the bolus, cricopharyngeal dysfunction, reduced laryngeal elevation, weak pharyngeal contraction, and velopharyngeal incompetence (Table 17.1).

2.

Inspection and Palpation

The shape, function, and sensitivity of anatomical structures related to swallowing are investigated by inspection and palpation.

3.

Ice Chip Swallow Test

The ice chip swallow test is a test for patients who are highly suspect for aspiration. The examiner places ice chips in a patient’s mouth and observes if the swallow reflex is delayed, for cough, or if voice alteration is present. In order to detect dysphagia, it is helpful to use cervical auscultation described below during this test. The cold stimulus of the ice chips is expected to trigger the pharyngeal swallow, and it is suitable not only as an assessment tool but also introductory swallowing material for direct swallow therapy.

4.

Laryngeal Elevation Test

Laryngeal elevation is one of the most essential components involved in swallowing. The extent and strength of the laryngeal elevation are assessed by placing the fingers at the thyroid cartilage of the patients when they swallow saliva. The extent of the laryngeal elevation in normal adults is about 1.5–2 cm (Fig. 17.5). Elevation under 1 cm is considered abnormal. The strength of the laryngeal elevation is considered normal when the index finger on the superior thyroid notch is flicked by the laryngeal elevation during the swallow (Fig. 17.6). For patients who have no signs of a pharyngeal swallow reflex, thermal–tactile stimulation to the anterior faucial pillars is given before performing the laryngeal elevation test.

Fig. 17.5

The extent of the laryngeal elevation is assessed by placing the fingers just above the thyroid cartilage of the patient during saliva swallow

Fig. 17.6

The strength of the laryngeal elevation is assessed by placing the fingers just above the thyroid cartilage of the patient during saliva swallow

5.

Timed Water Swallow Test

The timed water swallow test consists of the patient drinking 30 ml of water from a cup, with the examiner recording the time taken and number of swallows as well as noting the swallow-related episodes such as cough and wet/hoarse voice [15, 16]. Five seconds is considered as the threshold of dysphagia, and if a patient showed increase in duration and/or number of swallows, oral or pharyngeal swallow disorder is suspected. Because a large amount of water is swallowed in this test, it is not appropriate for patients who are suspected to have a severe swallowing disorder.

6.

Modified Water Swallow Test (MWST)

In the MWST, patients swallow 3 ml of cold water, and the presence of pharyngeal swallow reflex, cough, and respiratory change is recorded [17–19] (Table 17.2). This test is applicable for severe dysphagic patients. Combining this test with the cervical auscultation helps the examiner in detecting the occurrence of swallow.

Table 17.2

Scores and criteria of modified water swallow test (MWST)

Score | Criteria |

|---|---|

Score 1 | No swallow with/without dyspnea or cough |

Score 2 | Swallow with dyspnea (indication of silent aspiration) |

Score 3 | Swallow without dyspnea, but experienced cough or wet/hoarse voice |

Score 4 | Swallow without dyspnea nor cough |

Score 5 | Swallow without dyspnea nor cough, and perform two additional dry swallows within 30 s |

7.

Food Test (FT)

In the food test, patients swallow each of 4 g of pudding and 4 g of rice porridge, and the presence of pharyngeal swallow reflex, cough, and respiratory change is recorded as with the MWST [19, 20] (Table 17.3). Using the cervical auscultation with this test also is helpful in detecting dysphagia.

Table 17.3

Scores and criteria of food test (FT)

Score | Criteria |

|---|---|

Score 1 | No swallow with/without dyspnea or cough |

Score 2 | Swallow with dyspnea (indication of silent aspiration) |

SCORE 3 | Swallow without dyspnea, but experienced cough or wet/hoarse voice <25 % retention in oral cavity |

Score 4 | Swallow without dyspnea nor cough >25 % retention in oral cavity |

Score 5 | Swallow without dyspnea nor cough and perform two additional dry swallows within 30 s |

8.

Repetitive Saliva Swallowing Test (RSST)

The RSST is a screening test to evaluate if patients have an ability to initiate volitional swallow. In this test, patients are asked to repeat dry swallows (swallowing saliva) for 30 s, and the number of swallows is recorded. For patients with dry mouth, artificial saliva may be used to moisten the oral cavity before performing the dry swallow. Three repetitive dry swallows within 30 s is the threshold for the elderly [21, 22]. Combining this test with the laryngeal elevation test helps the examiner in detecting the occurrence of swallow (Fig. 17.7).

Fig. 17.7

The repetitive saliva swallowing test is a screening test to evaluate if patients have an ability to initiate volitional swallow. In this test, patients are asked to repeat dry swallows (swallowing saliva) for 30 s, and the number of swallows is recorded

17.2.2 Evaluation Using Simple Instruments: Cervical Auscultation

1.

What Is Cervical Auscultation?

Cervical auscultation is a technique used to evaluate the pharyngeal swallow by applying the stethoscope to the patient’s neck and listening to the swallow and respiratory sounds [23] (Fig. 17.8). The clinician listens and evaluates the characteristics and duration of swallowing sounds and the characteristics and timing of respiratory sounds. Cervical auscultation is a noninvasive screening tool for assessing the aspiration and pharyngeal retention, and it has been used widely in the clinical setting dealing with dysphagia.

Fig. 17.8

Cervical auscultation is a technique used to evaluate the pharyngeal swallow by applying the stethoscope to the patient’s neck and listening to the swallow and respiratory sounds

2.

Supplies Needed for Cervical Auscultation

(a)

Stethoscope

In cervical auscultation, a stethoscope is placed on a patient’s neck to identify the sounds. The cervical area is a relatively small region compared to the chest or abdomen which is the usual region for auscultation. For cervical auscultation, a pediatric stethoscope is recommended (Fig. 17.9).

Fig. 17.9

The cervical area is a relatively small region compared to the chest or abdomen which is the usual region for auscultation. For cervical auscultation, a pediatric stethoscope is recommended

(b)

Swallow Materials

For patients with severe swallowing disorders, a small amount of ice-cold water (1–2 ml) or few small ice chips are used. The movement of these ice-cold materials is easily noticed in the mouth and pharynx, and the cold stimulus is effective in triggering the pharyngeal swallow. Also, these materials can be cleared relatively easy, even if they are aspirated.

3.

Procedures for Cervical Auscultation

Before auscultation, the residual secretions in the oral cavity, pharynx, and larynx should be cleared in order to optimize the accuracy of the evaluation. Patients who are able to understand and follow the directions are instructed to clear the airway by strong voluntary cough or forced expiration (huffing). As the patient clears their secretions, they should bend forward with the trunk and neck lower than the horizontal angle of the body to get gravity assistance. If the airway is not cleared completely, suctioning is required. After airway clearance, the patient is asked to exhale, and the expiratory sound is auscultated. Then, as the swallowing material is given to the patient, the sounds produced during the swallow are evaluated. Finally, the patient is asked to exhale immediately after the swallow, and the expiratory sound is auscultated. Comparisons should be made between the pre-swallow expiratory sound and post-swallow expiratory sound to see if there is any alteration.

For patients who are not able to follow the directions, the residual secretions are cleared by suctioning. After the airway clearance, spontaneous respiratory sounds, swallow sounds, and post-swallow respiratory sounds are auscultated and evaluated, respectively.

The postural adjustment and bolus volume modification may be implemented as the evaluation proceeds. However, if severe aspiration is suspected, stop the evaluation, and suction aspirated material immediately.

4.

Interpreting the Sound Obtained by Cervical Auscultation

Prolonged or weak swallow sounds or multiple swallow sounds are associated with difficulties in bolus transport, pharyngeal contraction, laryngeal elevation, and cricopharyngeal opening. When a bubbling sound, throat clearing sound, or cough is heard during the swallow, aspiration is highly suspected. The presence of unexpected respiratory sounds during the swallow (respiratory sound during the apnea period) indicates laryngeal penetration (material enters the larynx, remains above the vocal folds), aspiration (material enters the airway, passes below the vocal folds), or swallow–respiration coordination (apnea–swallow–breathe sequence) disorder.

As for the respiratory (expiratory) sound after the swallow, a wet sound, gargling sound, or liquid vibrating sound (liquid vibration by the expiratory airflow at the airway actually witnessed in videofluoroscopic studies) is associated with laryngeal penetration, aspiration, or pharyngeal retention. Also, aspiration is suspected if wheezing sound, throat clearing, or cough is auscultated. In any case, it is important to clear the airway before the swallow to compare the respiratory (expiratory) sounds produced before and after the swallow (Table 17.4).

Table 17.4

Diagnosis and auditory characteristics of swallowing and expiratory sounds using cervical auscultation

Diagnosis | Diagnostic criteria (auditory characteristics) | |

|---|---|---|

Safe swallowb | 1. Normal | Clear swallowing and expiratory sounds |

2. Acceptable | Clear expiratory sounds, repeated or weak swallowing sounds | |

Dysphagic swallowb | 3. Residuea | Rough or gargling expiratory sounds after swallow, repeated or weak swallowing sounds |

4. Penetrationa | Rough or gargling expiratory sounds after swallow, repeatedly weak swallowing sounds, breathing while swallowing | |

5. Aspirationa | Rough or gargling expiratory sounds before/after swallow, repeatedly weak swallowing sounds, breathing while swallowing, uneven breathing, cough or slightly cough while/after swallow, liquid vibrating sound while expiration | |

5.

Accuracy of Cervical Auscultation for Detecting Dysphagia Evaluated by Acoustic Measurements and Auditory Assessment

Takahashi et al. evaluated the accuracy of cervical auscultation for detecting dysphagic swallows in head and neck cancer patients [24]. In this study, swallowing and respiratory sounds were detected by accelerometer attached to the neck and recorded on VHS tape with videofluorographic (VF) images. In the first half of this study, acoustic signals of swallowing sounds and expiratory sounds were analyzed using the computed analyzing system. 0.79 s of the duration of swallowing sounds and 25.3 dB of the revised magnitude of the 0 to 250Hz band of expiratory sound signals were set as the critical values in order to differentiate dysphagic swallows from safe swallows. Comparison of these assessments with the VF findings showed significant agreement. Both percent agreements were 77.3 % (102/132, 150/194). In the latter half of this study, swallowing sounds during swallows and expiratory sounds before and after swallows were edited and presented to six examiners through headphones. Without videofluorographic images, each examiner auditorily assigned the sound samples to one of two categories: safe swallow or dysphagic swallow. The percent agreement of auditory judgements with VF images was assessed. The percent agreement of two categories (safe swallow or dysphagic swallow) judged auditorily with VF images averaged 83.5 % (441/528). These results revealed the effectiveness of cervical auscultation as a clinical tool for diagnosing a dysphagic swallow in head and neck cancer patients.

17.2.3 Evaluations Using Special Instruments

1.

Videofluoroscopic Swallow Study (VFSS)

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

(a)

What is the videofluoroscopic swallow study?

The VFSS is considered to be the most reliable evaluation technique for dysphagia. The videofluoroscopic (VF) image gives information on the anatomy and physiology of the swallow-related structures and movement patterns of the radiopaque bolus. The observation of the image helps a clinician to determine the impaired region and evaluate dysphagic symptoms such as retention, laryngeal penetration, and aspiration. Aspiration is generally classified into three types (before, during, or after the swallow) according to the time of its occurrence relative to the triggering of the pharyngeal swallow. Aspiration before the swallow occurs before the pharyngeal swallow is triggered while the airway is still open. It may result from reduced tongue control and delayed or absent pharyngeal reflex. Aspiration during the swallow occurs if the laryngeal closure is inadequate. Aspiration after the swallow occurs when the larynx lowers and opens for inhalation. It may result from restriction in pharyngeal contraction, tongue base posterior movement, laryngeal elevation, laryngeal closure, or cricopharyngeal opening.

Normally, the lateral radiographic view is used to examine swallowing (Fig. 17.10). However, to evaluate the symmetry of the anatomical structures and bolus flow, the anterior–posterior view is used (Fig. 17.11). To evaluate the esophageal transit, the patient is imaged while standing obliquely (Fig. 17.12).

Fig. 17.10

An example of lateral view of the videofluoroscopic swallow study (VFSS). A red arrow shows aspiration of radiopaque material

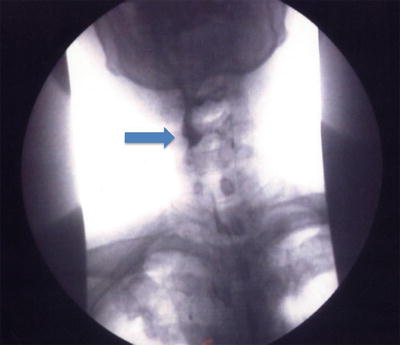

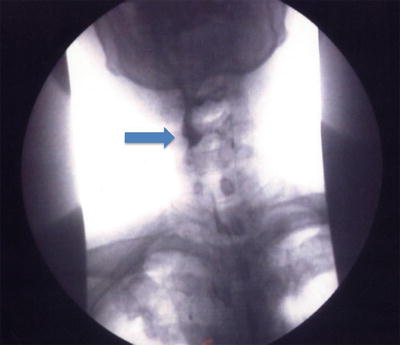

Fig. 17.11

The anterior–posterior view is used to evaluate the symmetry of the anatomical structures and bolus flow. A blue arrow shows radiopaque bolus entering the right pyriform sinus

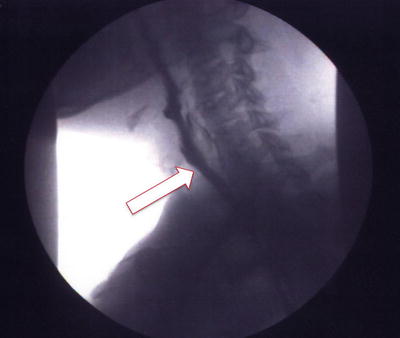

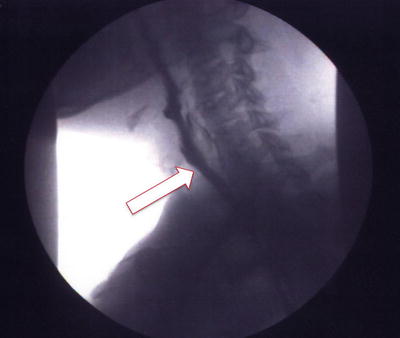

Fig. 17.12

The oblique view is used to evaluate the esophageal transit. A white arrow shows radiopaque bolus passing through the esophagus

Once the abnormalities in the patient’s anatomy and/or physiology of swallowing mechanism have been identified, the clinician should introduce treatment strategies during the VFSS. Such strategies usually include compensatory techniques (changing head or body posture, modifying viscosity and volume of bolus), thermal–tactile stimulation prior to the swallow, and swallow maneuvers. These strategies are introduced during the VFSS so that the clinician is able to evaluate the impact of the intervention.

(b)

A new system combining clinical information of the patient during VFSS and the VF images

VFSS is considered the gold standard examination for diagnosis of dysphagia. However, VFSS is the simple white and black silent movie lacking in important patient’s clinical information including physique, level of alertness, motivation, facial expression, posture, movement of swallow musculature, phonation, and respiratory, swallowing, and cough sounds.

We have built a new system to combine the important clinical information of dysphagic patient during the VFSS and VF images. Swallowing and respiratory sounds were detected and stored to the digital video recorder with VF images. By using another digital video recorder, subjects’ outward appearance during VFSS was recorded. The two digital video data of the patients’ outward appearance during VFSS and the VF images with the swallowing and respiratory sound signal were combined synchronously using the image editing system (Figs. 17.13 and 17.14). Our recent research indicates that the information acquired from VF images is insufficient to understand the clinical condition in the dysphagic patient. It is also revealed that additional information including the outward image of the patient during VFSS and detected swallowing and expiratory sounds plays an important role in realizing the dysphagic patient’s condition. A team approach by many members of the medical community including medical doctor, dentist, speech–language pathologist, nurse, dental hygienist, physiotherapist, occupational therapist, and dietician is very efficient in the management of dysphagia. Using our system, sharing the accurate information obtained from the VF images with the outward image of the patient during VFSS and swallowing and expiratory sounds among the medical members could produce high efficiency in the management of dysphagia.