Management of Disorders of the Ductal System and Infections

J. Michael Dixon

Nigel J. Bundred

Disorders of the ductal system can present as nipple discharge, nipple inversion, a breast mass, or periareolar infection.

NIPPLE DISCHARGE

Nipple discharge accounts for approximately 5% of referrals to breast clinics. It is a frightening symptom because of the fear of breast cancer. Approximately 95% of women presenting to the hospital with nipple discharge have a benign cause for the discharge. Discharge associated with a significant underlying pathologic process is spontaneous and more likely to be unilateral, arise from a single duct, be persistent (defined as more than twice per week), be troublesome, and be bloodstained or contain blood on testing. One study of 416 women with discharge identified bloody nipple discharge (odds ratio 3.7) and spontaneous discharge (odds ratio 3.2) as significant factors associated with a causative lesion (1).

For this reason, the physician must establish whether the discharge is spontaneous or induced, whether it arises from a single or from multiple ducts, and whether it is from one or both breasts. The characteristics of the discharge also need to be defined: whether it is serous, serosanguineous, bloody, clear, milky, green, or blue-black. The frequency of discharge and the amount of fluid also need to be assessed; this assessment is important for milky discharge, as galactorrhea should be diagnosed only if the milky discharge is spontaneous, copious in amount, and arises from multiple ducts of both breasts.

Investigations

Assessment should include the performance of a complete physical examination (Chapter 4) to identify the presence or absence of a breast mass. During the examination, firm pressure should be applied around the areola as pressure over a dilated duct will often produce the discharge; this is helpful in defining where an incision should be made for any subsequent surgery. The nipple is squeezed with firm digital pressure and, if fluid is expressed, the site and character of the discharge are recorded. Testing the discharge for hemoglobin determines whether blood is present. Bloody discharge increases the risks of cancer being the cause for the discharge with an odds ratio (OR) 2.27, 95% confidence intervals (CI) 1.32-3.89, p < .001. In a recent meta-analysis, up to 20% of patients who had a bloodstained discharge or who had a discharge containing moderate or large amounts of blood had an underlying malignancy (2). The absence of blood in nipple discharge is not an absolute indication that the discharge is not related to an underlying malignancy; in one series of 108 patients the sensitivity of hemoccult testing was only 50% (3). If the discharge is serous or colored but spontaneous and persistent, then malignancy still needs to be excluded. Age is said to be an important predictor of malignancy; in one series, 3% of patients younger than 40 years of age, 10% of patients between ages 40 and 60 years, and 32% of patients older than 60 years who presented with nipple discharge as their only symptom were found to have cancer. Cytology of nipple discharge is of little value in determining whether duct excision should be performed. In a recent study of 618 patients who had nipple discharge cytology, the sensitivity and specificity of cytology were 16.7% and 66.1%, respectively. In comparison, the sensitivity for macroscopically bloodstained discharge was 60.6% with a specificity at 53.6% (4). Although some studies have reported better results with cytology, the variability of reported results is such that it cannot be relied on in the routine assessment of nipple discharge.

Two related techniques have emerged: ductal lavage, in which fluid-yielding nipple ducts are cannulated at their

orifices and lavaged with saline while the breast is intermittently massaged (Chapter 20); and ductoscopy, in which discharging or fluid-yielding duct orifices are dilated and intubated with a microendoscope, and the lumen directly visualized. Both techniques have significant potential in terms of allowing repeated sampling of ductal epithelium over time and diagnosing the cause of nipple discharge (5). To learn ductoscopy takes longer than 6 months to overcome technical problems. Fiberoptic ductoscopy applied to 415 patients with nipple discharge was successful in identifying a lesion in 166 patients (40%) (6). Of these 166, 11 were subsequently shown to have ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS); ductoscopy was suspicious in 8, a sensitivity of 73%, with a specificity of 99% and a positive predictive value of 80% (6). DCIS in this series tended to affect more peripheral ducts compared with papillomas. Numerous other small series have evaluated ductoscopy in nipple discharge (7, 8). The sensitivity for malignancy in these other series varies from 81% to 100% (8). Ductoscopy appears of particular value for directing duct excision (7) and for detecting deeper lesions that can be missed by blind central duct excision (8). Surgical resection of lesions visualized on ductoscopy is facilitated by transillumination of the skin overlying the lesion. Lesions visualized by ductoscopy can be sampled; in one report, 38 of 46 women with biopsy-proved papillomas were observed for 2 years with no case of missed cancer becoming evident (8). Newer biopsy devices using vacuum assistance are now available for diagnostic assessment and can be ductoscope or sonograph guided.

orifices and lavaged with saline while the breast is intermittently massaged (Chapter 20); and ductoscopy, in which discharging or fluid-yielding duct orifices are dilated and intubated with a microendoscope, and the lumen directly visualized. Both techniques have significant potential in terms of allowing repeated sampling of ductal epithelium over time and diagnosing the cause of nipple discharge (5). To learn ductoscopy takes longer than 6 months to overcome technical problems. Fiberoptic ductoscopy applied to 415 patients with nipple discharge was successful in identifying a lesion in 166 patients (40%) (6). Of these 166, 11 were subsequently shown to have ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS); ductoscopy was suspicious in 8, a sensitivity of 73%, with a specificity of 99% and a positive predictive value of 80% (6). DCIS in this series tended to affect more peripheral ducts compared with papillomas. Numerous other small series have evaluated ductoscopy in nipple discharge (7, 8). The sensitivity for malignancy in these other series varies from 81% to 100% (8). Ductoscopy appears of particular value for directing duct excision (7) and for detecting deeper lesions that can be missed by blind central duct excision (8). Surgical resection of lesions visualized on ductoscopy is facilitated by transillumination of the skin overlying the lesion. Lesions visualized by ductoscopy can be sampled; in one report, 38 of 46 women with biopsy-proved papillomas were observed for 2 years with no case of missed cancer becoming evident (8). Newer biopsy devices using vacuum assistance are now available for diagnostic assessment and can be ductoscope or sonograph guided.

Ductal lavage increases cell yield approximately 100 times compared with analysis of discharge alone, averaging 5,000 cells per washed duct in one series (6). The sensitivity for cytology obtained by ductal lavage in this series was 64%, with a 100% positive predictive value. Other studies have reported lower sensitivities in the range of 50%, but a high specificity and a high overall accuracy rate (5). Both ductoscopy and ductal lavage remain investigative techniques, and the evidence that they are valuable in the detection of significant breast disease is limited.

Imaging of the ductal tree by ductography or galactography can identify intraductal lesions. Although this investigation has only a 60% sensitivity for malignancy, a filling defect or duct cutoff has a high positive predictive value for the presence of either a papilloma or a carcinoma (9). In one report, ductography-directed excisions were significantly more likely than central duct excisions to identify a specific underlying lesion (10). Ductography in one large study was, however, a poor predictor of underlying pathology and could not exclude malignancy (11). The value of ductography is that like ductoscopy, it can allow identification of the site of any lesion in younger women, allowing localization and excision of the causative lesion while retaining the ability to lactate.

Mammography has a high overall sensitivity for breast cancer, but not all malignant lesions that cause nipple discharge are visible mammographically and most patients with nipple discharge have negative mammograms (Chapter 12). In one series, the sensitivity of mammography for malignancy in patients with nipple discharge was only 57% with a positive predictive value of 16.7% and a negative predictive value of 91.4% (3). Nonetheless, mammography should be performed in women of appropriate age, because if a lesion is visualized it may help establish the cause of the discharge. Ultrasound has a low sensitivity for malignancy in patients with nipple discharge but is a valuable method for localizing intraductal abnormalities, especially papillomatous lesions, in patients with no other clinical or radiologic findings (12). Any lesion visualized can be biopsied by core biopsy or excised using a vacuumassisted large core biopsy device. (10, 13) Patients with a visible lesion on ultrasonography appear significantly more likely to have malignancy than those women with a negative scan (10).

Controversy surrounds the need to excise lesions seen on breast imaging and diagnosed as papillomas on core biopsy. Although it has been traditional to recommend excision of core biopsy-proven papillary lesions, imaging follow-up rather than excision may be safe providing there is imaging-histopathologic correlation and that all atypical and discordant lesions are excised (14). The use of vacuumassisted biopsy (VAB) to remove papillomas can avoid the need for surgical excision. In large papillomas, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may aid assessment of the presence of malignancy, which is more likely if an enhancing rim is seen. The use of MRI to evaluate the ductal tree is gaining interest but should not be part of the standard investigation of nipple discharge. In one series, MRI was performed in 52 patients with nipple discharge and had a positive predictive value of 56% with a negative predictive value of 87% (11) (Chapter 14).

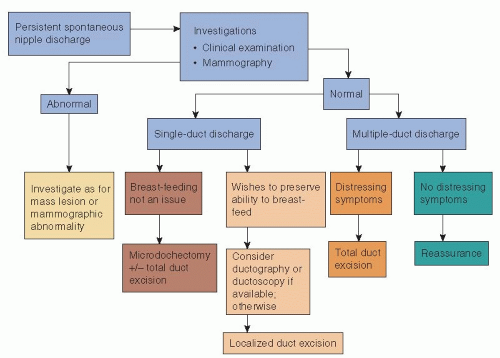

If clinical examination demonstrates a mass lesion or mammography or ultrasonography identifies an abnormality suspicious of malignancy, then core biopsy of the lesion should be performed and the lesion managed appropriately (Section VII: Management of Primary Invasive Breast Cancer). If no abnormality is found on clinical or mammographic examination, patients are treated according to whether the discharge is from a single duct or multiple ducts (Fig. 5-1). Surgery is indicated in cases of spontaneous discharge from a single duct that is confirmed on clinical examination and has one or more of the following characteristics:

Is bloodstained or contains moderate or large amounts of blood on testing

Is persistent and stains clothes (occurs on at least two occasions per week)

Is associated with a mass

Is a new development in a woman older than 50 years of age, but is not thick or cheesy

Discharge from multiple ducts normally requires surgery only when it causes distressing symptoms, such as persistent staining of clothes. Some breast units adopt an agerelated policy: Patients younger than age 30 years who have serous, serosanguineous, or watery discharge are observed, with microdochectomy reserved for cases in which discharge persists at review; patients older than 45 years of age are treated by a formal excision of the major duct system on the affected side; patients between 30 and 45 years of age are deemed suitable for either approach. The current evidence is that total duct excision is more effective than microdochectomy at establishing a specific diagnosis and has a lower chance of missing any underlying malignancy in women more than 40 years of age (15). Today, many units incorporate ductography and ductoscopy into their management protocols, particularly in younger women (Fig. 5-1). The problem is how to treat a patient with nipple discharge in whom imaging, including ductography or ductoscopy and ductal lavage, fails to identify any serious lesion. Some argue that as discharge from malignant disease is more likely to be bloodstained, there is no place for conservative management of bloodstained discharge and that all patients with bloodstained discharge should undergo duct excision unless investigation has identified a specific benign cause (16). Others argue that in selected patients, who have no clinical

or imaging abnormality, short-term observation with repeat evaluation is reasonable (17). A period of observation, particularly in younger women (≤35 years of age), is appropriate if the history of discharge is short but if spontaneous discharge persists (≥2 per week) at review 4 to 6 weeks later and the discharge can be expressed from a single duct on examination, then surgical excision is indicated to establish the cause of the discharge.

or imaging abnormality, short-term observation with repeat evaluation is reasonable (17). A period of observation, particularly in younger women (≤35 years of age), is appropriate if the history of discharge is short but if spontaneous discharge persists (≥2 per week) at review 4 to 6 weeks later and the discharge can be expressed from a single duct on examination, then surgical excision is indicated to establish the cause of the discharge.

Differential Diagnosis of Nipple Discharge

Physiologic Causes

In two-thirds of nonlactating women, a small quantity of fluid can be expressed from the ducts of the nipple if the nipple is cleaned, the breast massaged, and pressure applied. This fluid is physiologic secretion and varies in color from white to yellow to green to brown to blue-black; it is thought to represent apocrine secretion, as the breast is a modified apocrine gland. This physiologic secretion usually emanates from multiple ducts, and the discharge from each duct can vary in color. It is commonly found after pregnancy and is often noticed after a warm bath or after nipple manipulation. The discharge is not usually spontaneous or bloodstained and no specific treatment is required.

Intraductal Papilloma

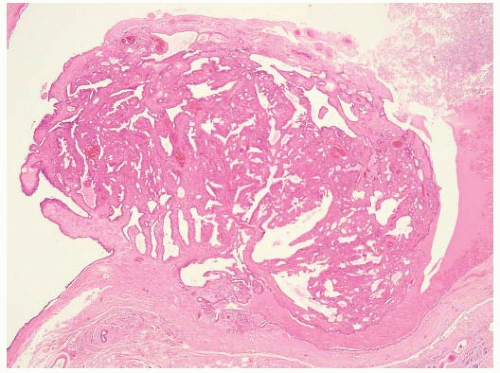

A true intraductal papilloma develops in one of the major subareolar ducts and is the most common lesion causing a serous or bloody nipple discharge. In approximately half of women with papillomas, the discharge is bloody; in the other half, it is serous (9). Papillomas should be differentiated from papillary hyperplasia, which affects the terminal duct lobular unit and can also cause nipple discharge. Central papillomas consist of epithelium covering arborescent fronds of fibrovascular stroma attached to the wall of the duct by a stalk (Fig. 5-2). The covering epithelium has a two-cell population, with a cuboidal or columnar cell lining covering an underlying layer of myoepithelial cells. A mass may be felt on examination in as many as one-third of cases. Occasionally, the papilloma is so close to the nipple that it can be seen in the orifice of the duct at the nipple. The treatment of choice is microdochectomy. A solitary papilloma is not thought to be a premalignant lesion and is considered by some to be an aberration rather than a true disease process. Papillary lesions can be difficult to characterize on core biopsies.

Multiple Intraductal Papillomas

In approximately 10% of patients with intraductal papillomas, multiple lesions are found; usually, two or three occur, often in the same duct. The term multiple intraductal papilloma syndrome is reserved for the rare and distinctive group of patients in whom one duct system contains five or more large and often palpable papillomas with a peripheral distribution. Nipple discharge is less common than in

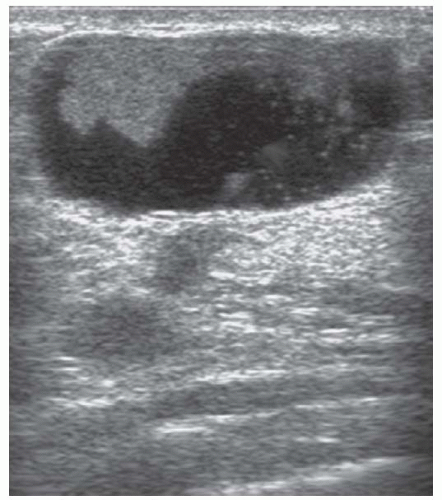

patients with a solitary intraductal papilloma. In one study, multiple papillomas were reported to be associated with an increased risk of breast cancer, but any increased risk is almost certainly associated with areas of atypical epithelial hyperplasia rather than with the papillomas themselves (18). Repeated excision of papillomas in patients with multiple intraductal papillomas can result in significant breast asymmetry. One option in such patients is to excise such lesions using ultrasound guidance by percutaneous vacuumassisted biopsy (Fig. 5-3). This provides sufficient material for the pathologist to assess whether lesions are benign and whether atypia is present. Some patients have multiple recurrent peripheral papillomas involving a whole ductal system and in such patients surgery to excise the affected ductal tree should be considered. A segmental excision is often possible with subsequent breast reshaping.

patients with a solitary intraductal papilloma. In one study, multiple papillomas were reported to be associated with an increased risk of breast cancer, but any increased risk is almost certainly associated with areas of atypical epithelial hyperplasia rather than with the papillomas themselves (18). Repeated excision of papillomas in patients with multiple intraductal papillomas can result in significant breast asymmetry. One option in such patients is to excise such lesions using ultrasound guidance by percutaneous vacuumassisted biopsy (Fig. 5-3). This provides sufficient material for the pathologist to assess whether lesions are benign and whether atypia is present. Some patients have multiple recurrent peripheral papillomas involving a whole ductal system and in such patients surgery to excise the affected ductal tree should be considered. A segmental excision is often possible with subsequent breast reshaping.

Juvenile Papillomatosis

A rare condition, juvenile papillomatosis, affects women between the ages of 10 and 44 years (19). The common presentation is nipple discharge +/- a discrete mass lesion. In one series of 13 patients, 11 had peripheral and 2 central lesions (19). Three of the 13 presented with nipple discharge; 2 had a palpable peripheral mass lesion, and the remainder had nipple discharge alone. Treatment is by complete excision. Patients with this condition may be at some increased risk of subsequent breast cancer, and close clinical and radiological surveillance of any woman with this condition is indicated.

Carcinoma

An invasive or noninvasive cancer can cause nipple discharge. Only rarely does an invasive cancer cause nipple discharge in the absence of a clinical mass. In most series, DCIS is responsible for up to 10% to 20% of unilateral spontaneous nipple discharges (2). Nipple discharge alone or in association with a mass or Paget’s disease is the presenting feature in approximately one-third of symptomatic in situ cancers. With the advent of mammography, increasing numbers of noninvasive cancers are being detected and, overall, nipple discharge is the presenting symptom in 7% to 8% of cases of DCIS (Chapter 25). Scant data exist on the frequency with which in situ cancers that cause nipple discharge are visible on mammography, but it is recognized that a significant percentage of malignant lesions causing nipple discharge are not visible on mammography. A diagnosis of invasive or noninvasive cancer is often established only by microdochectomy, but this operation is rarely, if ever, therapeutic. Despite a high rate of reported occult nipple-areolar complex involvement (20), a number of studies have demonstrated that breast-conserving surgery with nipple preservation is possible in patients presenting with DCIS or invasive carcinoma who have nipple discharge (21, 22 and 23). Bauer et al. in 1998 reported that 11 of 43 patients with breast cancer with nipple discharge were successfully treated by breast-conserving surgery. In the study by Cabioglu et al. (20), nipple preserving surgery was successfully performed in one-half of all patients presenting with breast cancer and nipple discharge. There were no local recurrences in those patients who had radiotherapy postoperatively. Concerns about the safety of nipple-preserving breast-conserving surgery in patients with nipple discharge were raised by the retrospective review of Obedian and Haffty (21). Local disease recurrence was noted in 6 of 17 patients with nipple discharge. Patients in this series who underwent central excisions incorporating the nipple had a lower recurrence rate than those patients who had conservation of the nipple-areolar complex. However, this difference did not reach significance. The problem with such retrospective series is that margins were not adequately documented in most patients. It cannot, therefore, be determined whether the high local recurrence rates reported by Obedian were attributable to residual tumor underneath the nipple. Although Cabioglu et al. (21) argue that long-term results obtained from larger series will be required before definitive conclusions can be drawn, they conclude that nipple-preserving breast-conserving surgery can be performed safely providing that negative margins are achieved and appropriate radiotherapy and systemic therapies are administered.

FIGURE 5-3 Ultrasound of an intraduct papilloma characteristic of those seen in multiple papilloma syndrome— such lesions can be excised by mammotomy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|